A Columbia (SC) Aviator and His Stinson Detroiter Remembered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coigneries/Converse & Redfern Family Tree

COIGNERIES/CONVERSE & REDFERN FAMILY TREE Last Update: January 1, 2021 (Public Version) Related Branches: Abrams, Aragon, Baker, Barons, Bates, Beaufort, Bedenbaugh, Betts, Blunt, Bohun, Booth, Brodzinski, Bucuski, Burnham, Cakandemir, Capps, Carr, Carter, Cecere, Chapman, Christofel, Clarke, Clough, Coachefer, Cochran, Conklin, Crutchfield, d’ Aton, Darcy, Davis, de Neville, Deady, Delgado, Dormer, Edmonds, Elliot, Escoto, Fetzner, Filmer, Fishburn, Flower, Garcia, Gleason, Goldstein, Giambalvo, Gilligan, Gonzales, Guilick, Gutierrez, Halford, Hall, Hammond, Harris, Hellmund, Hildebrandt, Hippie, Hochstetler, Homan, Hood, Howe, Hunt, Hutchison, Jansen, Jennings, Johns, Johnson, Joiner, Keeling, Kinley, Klein, Kowalski, Kujawski, Lake, le Scrope, Lewis, Linder, Lyon, Magda, Malnoski, Martinez, McDuffie, McPherson, Miller, Milner, Moser, Nisbit, Norton, Norwich, Nuss, O’Conner, Pain, Pert, Porter, Parkinson, Przymusik, Reaney, Reynolds, Reuckle, Rogers, Rollenston, Russell, Schrader, Schmid Routledge, Schreve, Seaman, Smalley, Snover, Sotelo, Spicer, Stanfield, Stanton, Stocks, Storch, Sutton, Swanson, Sykes, Talbot, Thomas, Thompson, Vanden Brul, Watkin, Widner, Winfield, Winn, Wolcott, Wooden, Yomboro, Young, Zelaya Many thanks to Dr. Frederick C. Redfern, Cherie Redfern, Geri Brodzinski and the many family members who generously contributed their time in researching the Coigneries/Converse & Redfern family tree and our many stories. In addition, special thanks to Erik Matthews of the Architectural & Archaeological Society of Durham and -

A Columbia Aviator and His Stinson Detroiter Remembered Paul Rinaldo Redfern

VOL. 30, No. 7 JULY 2002 STRAIGHT & LEVELlButchJoyce 2 VAA NEWS/H.G. Frautschy 4 MYSTERY PLANE/H.G. Frautschy 6 PAUL RINALDO REDFERN THE FIRST AVIATOR TO FLY SOLO ACROSS THE CARIBBEAN SEA/ Thomas Savage & Ron Shelton 10 JOHN MILLER RECALLS ... AVIATION IN THE 1920s/John M. Miller 13 HE SAID ...SHE SAID/Ken Morris 17 NEW LINDBERGH EXHIBIT MISSOURI HISTORICAL SOCIETY'S EXPANDED EXHIBITION SHOWCASES THE LIFE AND LEGEND OF CHARLES A. LINDBERGH! H.G. Frautschy 21 PASS IT TO BUCK/Buck Hilbert 22 CALENDAR 28 CLASSIFIED ADS 30 VAA MERCHANDISE WWW.VINTAGEAIRCRAFT.ORG Publisher TOM POBEREZNY Edltor-In-Chlef scon SPANGLER Executive mrector, Editor HENRY G. FRAUTSCHY VAA Administrative Assistant THERESA BOOKS Exeo.tive Editor MIKE DIFRISCO Contributing Editors JOHN UNDERWOOD BUDD DAVISSON Graphic Designer OLIVIA L. PHILLIP Photography Staff JIM KOEPNICK LEEANN ABRAMS Advertisblg!Edltorfal Assistant ISABELLE WISKE STRAIGHT Be LEVEL BY ESPIE "BUTCH" JOYCE PRESIDENT, VINTAGE ASSOCIATION EAA AirVenture's a Comin' s I write this there's about a of the field are not present during month to go before many of the midday and often make other Aus will gather in Oshkosh for arrangements for their evening EAA AirVenture. There's plenty to meal. We realize that may very do as we get ready. Like many of well be a /I chicken and egg" syn formation on this year's event. you, Norma and I will have to work drome and that there may be a On a more serious note, I've no a little harder and get quite a bit ac need for other meals, so we'll ticed that we've seen an increase in complished before we can take two closely monitor comments to re the accident rate for tailwheel weeks off to work and enjoy EAA fine our operation. -

One Summer: America, 1927 Notes on Sources

1 One Summer: America, 1927 Notes on Sources The following is a guide to sources used in One Summer: America, 1927, and is intended for those who wish to check a fact or do further reading. Where a fact is commonly known or widely reported – the date and place of Charles Lindbergh’s birth, for instance – I have not cited the source. On the whole, sources are listed only where assertions are specific, arguable or otherwise distinctively notable. Newspaper references are to page 1 stories unless otherwise noted. Because electronic archive retrievals do not often list page numbers, I have supplied the headline when the page number is unknown or uncertain. Prologue ‘Crowds flocked to Fifth Avenue to watch the blaze, the biggest the city had seen in years.’ New York Times, April 13, 1927. ‘They had been continuously airborne for 51 hours, 11 minutes and 25 seconds, an advance of nearly six hours on the existing record.’ New York Times, April 15, 1927. ‘It turned out that one of their ground crew, in a moment of excited distraction, had left their canteens filled with soapy water, so they had had nothing to drink for two days.’ Chamberlin, Record Flights, p. 21. ‘Just as significantly, they had managed to get airborne with 375 gallons of fuel, an enormous load for the time, and had used up just 1,200 feet of runway to do so.’ Chamberlin, Record Flights, pp. 19–23. ‘Germany, Britain, Italy, Russia, Japan, and Austria all had no more than four planes in their fleets; the United States had just two.’ Van Creveld, The Age of Airpower, p. -

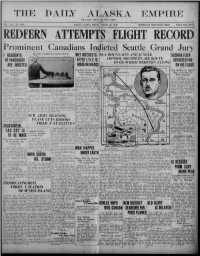

Redfern Attempts** Flight Record

THE DAILYEMPIRE "ALL THE NEWS A± THE TIME" I VOL. XXX., NO, 4568._ JUNEAU, ALASKA, FRIDAY, AUGUST 26, 1927. MEMBER OF ASSOCIATED PRESS PRICE TEN CENTS I REDFERN ATTEMPTS** FLIGHT RECORD Prominent Canadians Indicted Seattle Grand Jury I 7 RESIDENTS DEVISES GLIDER TO CROSS OCEAN WET INTERESTS SEA MOUNTAINS AND JUNGLE GEORGIA FLIER OF VANCOUVER AFTER LYLE IS IMPERIL SOUTHERN AIR ROUTE REPORTED FAR OVER WHICH REDFERN FLYING ARE INDICTED MADE IN CHARGE ON HIS FLIGHT Seattle Grand Jury Claims Anti-Saloon League Man in Paul Redfern Is Sighted Men Involved Liquor Seattle Exposes Al- High in Air Near the Conspiracy leged Conspiracy British Bahamas 26. — SEATTLE, Aug. 26. — Seven SEATTLE, Aug. B. N. ST PETERSBURG, Fla.. Aeg. of the residents of Vancouver, B. C.. Hicks, Superintendent 26.—A radio message from Nas- Anti-Saloon that Rome of them prominent in liquor League, charges sau. picked up by the Finauc al interests are exporting and distilling concerns, "liquor executing a I Journal's 40-meter station, said and well Move- are under indictment here on deep organixed the plane Port of Brunswick was ment to oust as charges of conspiracy to violate Roy Lyle Pacific sighted 300 miles east of the Northwest Prohibition the prohibition law Adminis- British Bahamas by a steamer ir. This was revealed when Fed- trator and put his place rome which arrived at Nassau at 11:40 eral Neterer released a se- wet who will not enforce the o’clock last Judge Adrien new night. The steamer Remy, French inventor, and his hydro-glider, with law." cret Indictment returnd by the reported the plane at an cross flying which he hopes to the Atlantic in four days. -

The Curve Marks the Spot” at Daytona International Airport

flwHBnEius OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF WOMEN PILOTS DECEMBER 1976 "The Curve Marks the Spot” at Daytona International Airport for the proposed site of the Women's International Air and Space Museum COVER STORY bilia cataloging are being carefully studied to coincide with the Universal Programs used by worldwide museums and libraries. * Letters of full cooperation have been received from our Professional Museum Advisors of the: Naval Aviation Museum The Air Force Museum The Smithsonian Air & Space Museum Condensed remarks before International contributions, my husband’s company is and 8 foreign Museum Directors have Convention in Philadelphia, August, 1976, providing a suite of furnished offices, a been contacted. by Doris Scott, President, secretary, supplies, telephones, warehouse We have officially received word from International Women’s Air & Space space and several other goodies, at “ NO the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum that Museum, Incorporated. CHARGE.” the restored Amelia Earhart Vega Aircraft Briefly, here are a few items of interest and Jerrie Mock’s airplane will be available that have been accomplished in just a few to the museum. Madam President, 99s and Friends, months: This Aviation Cultural Center with its Little did I know in August of 1973, * Ohio Incorporation was completed theater, auditorium, library, exhibits, dis when I attended my first 99s Convention in March 5, 1976. Non-Profit identification plays, educational sections, and many other Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and suggested Day status is granted. Previous Museum attractions, will be a means to inspire more ton, Ohio, “ the Birthplace of Aviation,” as Trust records are being collected for the young women, and yes, young men, to a possible site for the Museum, that I would archives. -

Converse/Redfern Family Tree and Related Branches

CONVERSE/REDFERN FAMILY TREE AND RELATED BRANCHES Last updated August 21, 2012 Many thanks to Dr. Frederick C. Redfern, Cherie Redfern, Geri Brodzinski, and the many family members who generously contributed their time in researching the Converse/Redfern family tree and our many stories. In addition, special thanks to Erik Matthews of the Architectural & Archaeological Society of Durham and Northumberland, England and Joe Iamartino, historian, Thompson, CT. “When we respect our blood ancestors and our spiritual ancestors, we feel rooted.” – Thich Nhat Hanh. The numbers in the left column, such as 29 (12) means the 29th generation from 1010 (when the family tree starts) and the 12th generation from Deacon Edward Converse (the first direct line family member in America). The individuals in this tree (without all the stories in this document) are entered in ancestry.com under “Redfern Family” tree, but ancestry.com is fee-based and lineages and relations are somewhat challenging to follow since that site does not identify living relatives. I have entered a more extensive branch at ancestry.com however. Enjoy our family stories, I certainly have. Thank you one and all, Love, Paul p.s. any additions or changes are welcomed. Please send them to me at [email protected] and [email protected] (both addresses please, thanks). I do plan to update this document (once in a blue moon). The de Coigneries family was in France before William of Normandy (1028-1087) and was active in its political history. The original seat of the Converse family was in Navarre, France, whence was Roger de Coigneries, who immigrated to England and became Constable of Durham about 1087, at the time of the death of William the Conqueror. -

The Foreign Service Journal, May 1938

<7/« AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ★ * JOURNAL * * WHY A TELEPHONE GIRL TEACHES OUR BELL-BOYS From Our Book of Permanent Set-ups SERVICE DEPARTMENT — Voice culture for bellmen trainees: classes are to be conducted by the Chief Telephone Operator who will teach diction and pronuncia¬ tion. WE BELIEVE YOU appreciate having a Hotel New Yorker bellman call your name clearly . correctly. That’s why we have our tele¬ phone girls teach them how. It’s only a detail. But we’ve made “set-ups,” or rules, of more than 2,000 details. They control everything at the New Yorker . from the way our bellman folds your coat in packing ... to the way our chambermaid turns down your bed each night. All together, these 2,000 “set¬ ups” assure that Hotel New York¬ er service . the result of new, forward-marching ideas in hotel management ... is the finest hotel service you’ve ever had! We’d like to prove this to you the next time you take a trip to New York City. Maids at the Hotel New After learning her “set-ups,” Here’s a typical N. H. M. “set¬ PRESIDENT Yorker go to a training school and passing tests, the maid is up”: telephones in all rooms —the first in hotel history. qualified to clean your room. are disinfected regularly. National Hotel Management Co., Inc. 34TH STREET AT EIGHTH HOTEL NEW YORKER AVENUE Ralph Hits, President George V. Riley, Manager NEW YORK 25% REDUCTION TO DIPLOMATIC AND CONSULAR SERVICE. - - NOTE: THE SPECIAL RATE REDUCTION APPLIES ONLY TO ROOMS ON WHICH THE RATE IS $5 A DAY OR MORE. -

Netherlands Philately Vol. 33, No. 3 1 Paul Redfern Rescue Expedition

The Paul Redfern Rescue Expedition of 1936 By Hans Kremer Paul Redfern Rescue Expedition cover sent in 1936 from Suriname to the Canal Zone Van Dieten’s Auction # 612 (May 2008) showed the months later, A.C. Goebel won the $25,000 Dole Race above cover, dated April 29, 1936, canceled in from Oakland to Honolulu. Not wanting to be left out Albina, Suriname. I’ve seen another addressed to the of the fame and fortune that hit the aviation world, Paul Canal Zone and one sent to the Netherlands (Wiggers de persuaded the Brunswick (Ga.) Board of Trade that a Vries auction # $25,000 record- setting flight from Brunswick to Rio 187. lot 553). would help them become a major port city. Netherlands Philately, Vol. 15 Some legwork on the Internet, N.Y Times archives # 1 also shows plus other resources brought me to the following story, one of these whch gives a fairly detailed report about Paul Redferns’ covers. ill fated flight. The covers refer to From TIME Magazine of March 2, 1936 the “Waid Post “Paul Redfern American Legion On Aug. 25, 1927 a slim, wide-mouthed young man Paul Redfern named Paul Redfern took off from Brunswick, Ga. to Rescue Expedition fly to Brazil. Some 27 hours later Pilot Redfern's - Dutch Guiana. single-motored monoplane swooped down over the Paul Redfern Jan. 1936” Norwegian freighter Christian Krohg 200 miles out of La Guaira, Venezuela. Getting his bearings, Redfern dashed on toward South America, where he was later reported over the Orinoco Delta. Then he vanished. -

Converse/Redfern Family Tree and Related Branches

CONVERSE/REDFERN FAMILY TREE AND RELATED BRANCHES Last updated January 28, 2012 Many thanks to Dr. Frederick C. Redfern, Cherie Redfern, Geri Brodzinski, and the many family members who generously contributed their time in researching the Converse/Redfern family tree and our many stories. In addition, special thanks to Erik Matthews of the Architectural & Archaeological Society of Durham and Northumberland, England and Joe Iamartino, historian, Thompson, CT. “When we respect our blood ancestors and our spiritual ancestors, we feel rooted.” – Thich Nhat Hanh. The numbers in the left column, such as 29 (12) means the 29th generation from 1010 (when the family tree starts) and the 12th generation from Deacon Edward Converse (the first direct line family member in America). The individuals in this tree (without all the stories in this document) are entered in ancestry.com under “Redfern Family” tree, but ancestry.com is fee-based and lineages and relations are somewhat challenging to follow since that site does not identify living relatives. I have entered a more extensive branch at ancestry.com however. Enjoy our family stories, I certainly have. Thank you one and all, Love, Paul p.s. any additions or changes are welcomed. Please send them to me at [email protected] and [email protected] (both addresses please, thanks). I do plan to update this document (once in a blue moon). The de Coigneries family was in France before William of Normandy (1028-1087) and was active in its political history. The original seat of the Converse family was in Navarre, France, whence was Roger de Coigneries, who immigrated to England and became Constable of Durham about 1087, at the time of the death of William the Conqueror.