One Summer: America, 1927 Notes on Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Orteig Prize Tim Brady [email protected]

Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research Volume 12 Article 9 Number 1 JAAER Fall 2002 Fall 2002 The Orteig Prize Tim Brady [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/jaaer Scholarly Commons Citation Brady, T. (2002). The Orteig Prize. Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.15394/ jaaer.2002.1595 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Aviation/ Aerospace Education & Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Brady: The Orteig Prize The Orteig Prize THE ORTEIG PMZE Tim Brady Science, fieedom, beauty, adventure: What more could you ask of life? Aviation combined all of the elements I loved. There was science in each curve of an airfoiil . There wasfieedom in the unlimited horizon. A pilot was surrounded by beauty of earth and sky... Adventure lay in each pufof wind' Charles A. Lindbergh It can be reasonably argued that, apart from the Wnght brothers' epic flight of 1903, which ushered the world into gviation, the sm@e most important flight made in the twentieth century was the transatlantic flight made by Charles A. Lindbergh in May 1927. The economic impact of this solo flight was whose GNP had plummeted 45% in a raging depression. astonishing. For example, in the three-year period The average annual income dropped from $1,350 in 1929 following the flight, the number of passengers carried to $754 in 1933. -

Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2019 Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927 Ryan C. Ferro University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ferro, Ryan C., "Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7785 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist-Guomindang Split of 1927 by Ryan C. Ferro A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-MaJor Professor: Golfo Alexopoulos, Ph.D. Co-MaJor Professor: Kees Boterbloem, Ph.D. Iwa Nawrocki, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 8, 2019 Keywords: United Front, Modern China, Revolution, Mao, Jiang Copyright © 2019, Ryan C. Ferro i Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………….…...ii Chapter One: Introduction…..…………...………………………………………………...……...1 1920s China-Historiographical Overview………………………………………...………5 China’s Long -

Commission Meeting of NEW JERSEY GENERAL AVIATION STUDY COMMISSION

Commission Meeting of NEW JERSEY GENERAL AVIATION STUDY COMMISSION LOCATION: Committee Room 16 DATE: March 27, 1996 State House Annex 10:00 a.m. Trenton, New Jersey MEMBERS OF COMMISSION PRESENT: John J. McNamara Jr., Esq., Chairman Linda Castner Jack Elliott Philip W. Engle Peter S. Hines ALSO PRESENT: Robert B. Yudin (representing Gualberto Medina) Huntley A. Lawrence (representing Ben DeCosta) Kevin J. Donahue Office of Legislative Services Meeting Recorded and Transcribed by The Office of Legislative Services, Public Information Office, Hearing Unit, State House Annex, CN 068, Trenton, New Jersey TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Dennis Yap DY Consultants representing Trenton-Robbinsville Airport 2 John F. Bickel, P.E. Township Engineer Oldmans Township, New Jersey 24 Kristina Hadinger, Esq. Township Attorney Montgomery Township, New Jersey 40 Donald W. Matthews Mayor Montgomery Township, New Jersey 40 Peter Rayner Township Administrator Montgomery Township, New Jersey 42 Patrick Reilly Curator Aviation Hall of Fame and Museum 109 Ronald Perrine Deputy Mayor Alexandria Township, New Jersey 130 Barry Clark Township Administrator/ Chief Financial Officer Readington Township, New Jersey 156 Benjamin DeCosta General Manager New Jersey Airports Port Authority of New York and New Jersey 212 APPENDIX: TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued) Page “Township of Readington Resolution” submitted by Barry Clark 1x mjz: 1-228 (Internet edition 1997) PHILIP W. ENGLE (Member of Commission): While we are waiting for Jack McNamara, why don’t we call this meeting of the New Jersey General Aviation Study Commission to order. We will have a roll call. Abe Abuchowski? (no response) Assemblyman Richard Bagger? (no response) Linda Castner? (no response) Huntley Lawrence? Oh, he is on the way. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

Bronx Civic Center

Prepared for New York State BRONX CIVIC CENTER Downtown Revitalization Initiative Downtown Revitalization Initiative New York City Strategic Investment Plan March 2018 BRONX CIVIC CENTER LOCAL PLANNING COMMITTEE Co-Chairs Hon. Ruben Diaz Jr., Bronx Borough President Marlene Cintron, Bronx Overall Economic Development Corporation Daniel Barber, NYCHA Citywide Council of Presidents Michael Brady, Third Avenue BID Steven Brown, SoBRO Jessica Clemente, Nos Quedamos Michelle Daniels, The Bronx Rox Dr. David Goméz, Hostos Community College Shantel Jackson, Concourse Village Resident Leader Cedric Loftin, Bronx Community Board 1 Nick Lugo, NYC Hispanic Chamber of Commerce Milton Nuñez, NYC Health + Hospitals/Lincoln Paul Philps, Bronx Community Board 4 Klaudio Rodriguez, Bronx Museum of the Arts Rosalba Rolón, Pregones Theater/Puerto Rican Traveling Theater Pierina Ana Sanchez, Regional Plan Association Dr. Vinton Thompson, Metropolitan College of New York Eileen Torres, BronxWorks Bronx Borough President’s Office Team James Rausse, AICP, Director of Planning and Development Jessica Cruz, Lead Planner Raymond Sanchez, Counsel & Senior Policy Manager (former) Dirk McCall, Director of External Affairs This document was developed by the Bronx Civic Center Local Planning Committee as part of the Downtown Revitalization Initiative and was supported by the NYS Department of State, NYS Homes and Community Renewal, and Empire State Development. The document was prepared by a Consulting Team led by HR&A Advisors and supported by Beyer Blinder Belle, -

NLDS Notes GM 4.Indd

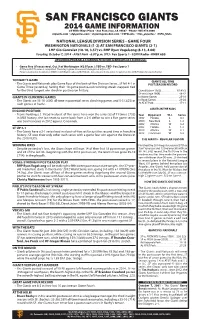

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS 2014 GAME INFORMATION 24 Willie Mays Plaza •San Francisco, CA 94107 •Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com •sfgigantes.com •sfgiantspressbox.com •@SFGiants •@los_gigantes• @SFG_Stats NATIONAL LEAGUE DIVISION SERIES - GAME FOUR WASHINGTON NATIONALS (1-2) AT SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (2-1) LHP Gio Gonzalez (10-10, 3.57) vs. RHP Ryan Vogelsong (8-13, 4.00) Tuesday, October 7, 2014 • AT&T Park • 6:07 p.m. (PT) • Fox Sports 1 • ESPN Radio • KNBR 680 UPCOMING PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS & BROADCAST SCHEDULE: • Game Five (if necessary), Oct. 9 at Washington (#2:07p.m.): TBD vs. TBD- Fox Sports 1 # If the LAD/STL series is completed, Thursday's game time would change to 5:37p.m. PT Please note all games broadcast on KNBR 680 AM (English radio) and ESPN Radio. All postseason home games broadcast on 860 AM ESPN Deportes (Spanish radio). TONIGHT'S GAME GIANTS ALL-TIME • The Giants and Nationals play Game Four of this best-of- ve Division Series...SF fell 4-1 in POSTSEASON RECORD Game Three yesterday, having their 10-game postseason winning streak snapped, tied for the third-longest win streak in postseason history. Overall (since 1900) . 87-83-2 SF-era (since 1958) . .48-42 GIANTS IN CLINCHING GAMES In Home Games . .25-18 • The Giants are 15-10 (.600) all-time in potential series clinching games and 5-3 (.625) in In Road Games. .23-24 such games at home. At AT&T Park . .17-11 GIANTS IN THE NLDS IN GOOD POSITION • Teams holding a 2-1 lead in a best-of- ve series have won the series 52 of 71 times (.732) Year Opponent W-L Series in MLB history...the last team to come back from a 2-0 de cit to win a ve game series 1997 Florida L 0-3 was San Francisco in 2012 against Cincinnati. -

An Introduction to Jere Abbott's Russian Diary, 1927–1928*

An Introduction to Jere Abbott’s Russian Diary, 1927 –1928* LEAH DICKERMAN In 1978, in its seventh issue, October published the travel diaries written by Alfred H. Barr, Jr., who would go on to become the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, during his two-month sojourn in Russia in 1927–28. They were accompanied by a note from Barr’s wife, Margaret Scolari Barr, who had made the documents available, and an introduction written by Jere Abbott, an art historian and former director of the Smith College Museum of Art who had returned to his family’s textile business in Maine. Abbott and Barr had made the journey together, traveling from London in October 1927 to Holland and Germany (including a four-day visit to the Bauhaus) and then, on Christmas Day 1927, over the border into Soviet Russia. Abbott, as Margaret Barr had noted, kept his own journal on the trip. Abbott’s, if anything, was more detailed and expansive in documenting its author’s observations and perceptions of Soviet cultural life at this pivotal moment; and his perspective offers both a complement and counter - point to Barr’s. Russia after the revolution was largely uncharted territory for Anglophone cultural commentary: This, in combination with the two men’s deep interest in and knowledge of contemporary art, makes their journals rare docu - ments of the Soviet cultural terrain in the late 1920s. We present Abbott’s diaries here, thirty-five years after the publication of Barr’s, with thanks to the generous cooperation of the Smith College Museum of Art, where they are now held. -

2017 Information & Record Book

2017 INFORMATION & RECORD BOOK OWNERSHIP OF THE CLEVELAND INDIANS Paul J. Dolan John Sherman Owner/Chairman/Chief Executive Of¿ cer Vice Chairman The Dolan family's ownership of the Cleveland Indians enters its 18th season in 2017, while John Sherman was announced as Vice Chairman and minority ownership partner of the Paul Dolan begins his ¿ fth campaign as the primary control person of the franchise after Cleveland Indians on August 19, 2016. being formally approved by Major League Baseball on Jan. 10, 2013. Paul continues to A long-time entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sherman has been responsible for establishing serve as Chairman and Chief Executive Of¿ cer of the Indians, roles that he accepted prior two successful businesses in Kansas City, Missouri and has provided extensive charitable to the 2011 season. He began as Vice President, General Counsel of the Indians upon support throughout surrounding communities. joining the organization in 2000 and later served as the club's President from 2004-10. His ¿ rst startup, LPG Services Group, grew rapidly and merged with Dynegy (NYSE:DYN) Paul was born and raised in nearby Chardon, Ohio where he attended high school at in 1996. Sherman later founded Inergy L.P., which went public in 2001. He led Inergy Gilmour Academy in Gates Mills. He graduated with a B.A. degree from St. Lawrence through a period of tremendous growth, merging it with Crestwood Holdings in 2013, University in 1980 and received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s and continues to serve on the board of [now] Crestwood Equity Partners (NYSE:CEQP). -

Chapter III 1927 – Year for Heroes and Headlines

Chapter III 1927 – Year for Heroes and Headlines The year 1927 was called a time of Ballyhoo and Ford and the Hamilton, “fireproof, you know;” they Hoopla and Wonderful Nonsense, a time when stared at the new Stinson, “built right here in everything was bigger and crazier and publicized Northville;” they tugged at the taut wires of the with more headlines than anything that ever sturdy Wacos and peered inside the cabin of the happened before. yellow painted Ryan, said to be just like Lindy’s, It was a time for Home Run Kings and Flagpole except this one was all fixed up with blue mohair Sitters, Beauty Queens and Talking Movies, Race seats like a fine automobile. Riots and Lynchings and Chicago Gang Wars, The spectators watched the airplanes run through Mississippi Floods and Big Radio Broadcast Hook- their takeoff and landing tests and they talked of Ups and Record Airplane Flights. People called one newsreel pictures they’d seen: of transatlantic another Sheiks, and Shebas; they said things like record seekers struggling to take off; “make their “You’re darned tootin,” and “he knows his onions.” getaway,” as the papers called it, dangerously Flaming Youth drove their Whoopies down the overloaded with hundreds of gallons of “high Main Drag and picked up Daring Flappers who test gasoline.” wore their skirts Two Inches Above the Knee and And the tour officials, mindful of all this scare smoked Tailor-Mades and drank Bootleg Hooch talk, changed the rules to eliminate the full-throttle from Hip Flasks just like their Boy Friends did. -

December 1927) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 12-1-1927 Volume 45, Number 12 (December 1927) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 45, Number 12 (December 1927)." , (1927). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/46 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r 7'he Journal of the iMusjcal Home Everywhere THE ETUDE <Music HhCasazine A CHRISTMAS EVE DILEMMA PRICE 25 CENTS December I92^ $2.oo A YEAR D Acquaintance with thex ComposenjmA^^--rZT —1---. asr-TSS-feiJs Z »*• s 126 S5S?-* o/l favorite American and European Composers. THE WORLD OF -MUSIC Interesting and Important Items Gleaned in a Constant Watch on Happenings and Activities Pertaining to Things Musical Everywhere THE ETUDE THE ETUDE DECEMBER 1927 Page SS3 Page 882 DECEMBER 1927 Professional WHAT TO DO FIRST AT Directory ■ Qan You THE PIANO THE ETUDE MUSIC MA®AZlNE Founded by Theodore Pres'er’ „ --- eastern 1. Why ir, the Dominant Chord so called? By Helen L. Cramm “Music for 2. -

National Prohibition and Jazz Age Literature, 1920-1933

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine English and Technical Communication Faculty Research & Creative Works English and Technical Communication 01 Jan 2005 Spirits of Defiance: National Prohibition and Jazz Age Literature, 1920-1933 Kathleen Morgan Drowne Missouri University of Science and Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/eng_teccom_facwork Part of the Business and Corporate Communications Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Drowne, Kathleen. "Spirits of Defiance: National Prohibition and Jazz Age Literature, 1920-1933." Columbus, Ohio, The Ohio State University Press, 2005. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in English and Technical Communication Faculty Research & Creative Works by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Drowne_FM_3rd.qxp 9/16/2005 4:46 PM Page i SPIRITS OF DEFIANCE Drowne_FM_3rd.qxp 9/16/2005 4:46 PM Page iii Spirits of Defiance NATIONAL PROHIBITION AND JAZZ AGE LITERATURE, 1920–1933 Kathleen Drowne The Ohio State University Press Columbus Drowne_FM_3rd.qxp 9/16/2005 4:46 PM Page iv Copyright © 2005 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Drowne, Kathleen Morgan. Spirits of defiance : national prohibition and jazz age literature, 1920–1933 / Kathleen Drowne. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–8142–0997–1 (alk. paper)—ISBN 0–8142–5142–0 (pbk. -

Strafford, Missouri Bank Books (C0056A)

Strafford, Missouri Bank Books (C0056A) Collection Number: C0056A Collection Title: Strafford, Missouri Bank Books Dates: 1910-1938 Creator: Strafford, Missouri Bank Abstract: Records of the bank include balance books, collection register, daily statement registers, day books, deposit certificate register, discount registers, distribution of expense accounts register, draft registers, inventory book, ledgers, notes due books, record book containing minutes of the stockholders meetings, statement books, and stock certificate register. Collection Size: 26 rolls of microfilm (114 volumes only on microfilm) Language: Collection materials are in English. Repository: The State Historical Society of Missouri Restrictions on Access: Collection is open for research. This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Columbia. you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Collections may be viewed at any research center. Restrictions on Use: The donor has given and assigned to the University all rights of copyright, which the donor has in the Materials and in such of the Donor’s works as may be found among any collections of Materials received by the University from others. Preferred Citation: [Specific item; box number; folder number] Strafford, Missouri Bank Books (C0056A); The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Columbia [after first mention may be abbreviated to SHSMO-Columbia]. Donor Information: The records were donated to the University of Missouri by Charles E. Ginn in May 1944 (Accession No. CA0129). Processed by: Processed by The State Historical Society of Missouri-Columbia staff, date unknown. Finding aid revised by John C. Konzal, April 22, 2020. (C0056A) Strafford, Missouri Bank Books Page 2 Historical Note: The southern Missouri bank was established in 1910 and closed in 1938.