Slide 1: Title Producing Bollywood: Sustainability and the Impacts On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume-13-Skipper-1568-Songs.Pdf

HINDI 1568 Song No. Song Name Singer Album Song In 14131 Aa Aa Bhi Ja Lata Mangeshkar Tesri Kasam Volume-6 14039 Aa Dance Karen Thora Romance AshaKare Bhonsle Mohammed Rafi Khandan Volume-5 14208 Aa Ha Haa Naino Ke Kishore Kumar Hamaare Tumhare Volume-3 14040 Aa Hosh Mein Sun Suresh Wadkar Vidhaata Volume-9 14041 Aa Ja Meri Jaan Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Jawab Volume-3 14042 Aa Ja Re Aa Ja Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Ankh Micholi Volume-3 13615 Aa Mere Humjoli Aa Lata Mangeshkar Mohammed RafJeene Ki Raah Volume-6 13616 Aa Meri Jaan Lata Mangeshkar Chandni Volume-6 12605 Aa Mohabbat Ki Basti BasayengeKishore Kumar Lata MangeshkarFareb Volume-3 13617 Aadmi Zindagi Mohd Aziz Vishwatma Volume-9 14209 Aage Se Dekho Peechhe Se Kishore Kumar Amit Kumar Ghazab Volume-3 14344 Aah Ko Chahiye Ghulam Ali Rooh E Ghazal Ghulam AliVolume-12 14132 Aah Ko Chajiye Jagjit Singh Mirza Ghalib Volume-9 13618 Aai Baharon Ki Sham Mohammed Rafi Wapas Volume-4 14133 Aai Karke Singaar Lata Mangeshkar Do Anjaane Volume-6 13619 Aaina Hai Mera Chehra Lata Mangeshkar Asha Bhonsle SuAaina Volume-6 13620 Aaina Mujhse Meri Talat Aziz Suraj Sanim Daddy Volume-9 14506 Aaiye Barishon Ka Mausam Pankaj Udhas Chandi Jaisa Rang Hai TeraVolume-12 14043 Aaiye Huzoor Aaiye Na Asha Bhonsle Karmayogi Volume-5 14345 Aaj Ek Ajnabi Se Ashok Khosla Mulaqat Ashok Khosla Volume-12 14346 Aaj Hum Bichade Hai Jagjit Singh Love Is Blind Volume-12 12404 Aaj Is Darja Pila Do Ki Mohammed Rafi Vaasana Volume-4 14436 Aaj Kal Shauqe Deedar Hai Asha Bhosle Mohammed Rafi Leader Volume-5 14044 Aaj -

Indian Singers' Rights Association

INDIANINDIAN SINGERS’SINGERS’ RIGHTSRIGHTS ASASSOCIASOCIATIONTION Annual Report 2017-18 BOARD OF ADVISORS LATA MANGESHKAR SURESH WADKAR TALAT AZIZ SONU NIGAM SANJAY TANDON BOARD OF DIRECTORS ANUP JALOTA A HARIHARAN KAVITA KRISHNAMURTI S P BALASUBRAHMANIYAM PANKAJ UDHAS SHANTANU MUKHERJEE SRINIVASAN ALKA YAGNIK JASBIR JASSI SHAILENDRA SINGH DORAISWAMY INDIAN SINGERS’ RIGHTS ASSOCIATION 2208, Lantana, Nahar Amrit Shakti, Chandivali, Andheri (E), Mumbai 400 072 NOTICE NOTICE is hereby given that the Meeting of the General Body of the Society will be held at “Eden Hall”, The Classique Club, Behind Infinity Mall, Link Road, Oshiwara, Andheri (W), Mumbai 400 053 on Thursday, 20th September, 2018 at 3pm to transact the following business: ORDINARY BUSINESS: 1. To receive, consider and adopt the Audited Balance Sheet as on 31st March 2018, Statement of Income and Expenditure for the year ended on that date, and the Auditors Report thereon, together with the Directors’ Report as approved by the Board of Directors for the period ending 31st March, 2018. 2. To ratify the appointment of M/s. Kothari Mehta & Associates as the Statutory Auditors of the Company for the financial year ending 31st March, 2019 by passing the following resolution :- “RESOLVED THAT pursuant to provisions of Section 139, 141, 142 and all other applicable provisions, if any, of the Companies Act, 2013 read with Rule 3 of the Companies (Audit and Auditors) Rules, 2014 and pursuant to the resolution passed at the Annual General Meeting of the Company held on September 29, 2014, the consent of the members of the Company be and is hereby accorded to ratify the appointment of M/s. -

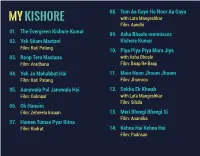

Kishore Booklet Copy

08. Tum Aa Gaye Ho Noor Aa Gaya with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Aandhi 01. The Evergreen Kishore Kumar 09. Asha Bhosle reminisces 02. Yeh Sham Mastani Kishore Kumar Film: Kati Patang 10. Piya Piya Piya Mora Jiya 03. Roop Tera Mastana with Asha Bhosle Film: Aradhana Film: Baap Re Baap 04. Yeh Jo Mohabbat Hai 11. Main Hoon Jhoom Jhoom Film: Kati Patang Film: Jhumroo 05. Aanewala Pal Janewala Hai 12. Dekha Ek Khwab Film: Golmaal with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Silsila 06. Oh Hansini Film: Zehreela Insaan 13. Meri Bheegi Bheegi Si Film: Anamika 07. Hamen Tumse Pyar Kitna Film: Kudrat 14. Kehna Hai Kehna Hai Film: Padosan 2 3 15. Raat Kali Ek Khwab Mein 23. Mere Sapnon Ki Rani Film: Buddha Mil Gaya Film: Aradhana 16. Aate Jate Khoobsurat Awara 24. Dil Hai Mera Dil Film: Anurodh Film: Paraya Dhan 17. Khwab Ho Tum Ya Koi 25. Mere Dil Mein Aaj Kya Hai Film: Teen Devian Film: Daag 18. Aasman Ke Neeche 26. Ghum Hai Kisi Ke Pyar Mein with Lata Mangeshkar with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Jewel Thief Film: Raampur Ka Lakshman 19. Mere Mehboob Qayamat Hogi 27. Aap Ki Ankhon Mein Kuch Film: Mr. X In Bombay with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Ghar 20. Teri Duniya Se Hoke Film: Pavitra Papi 28. Sama Hai Suhana Suhana Film: Ghar Ghar Ki Kahani 21. Kuchh To Log Kahenge Film: Amar Prem 29. O Mere Dil Ke Chain Film: Mere Jeevan Saathi 22. Rajesh Khanna talks about Kishore Kumar 4 5 30. Musafir Hoon Yaron 38. Gaata Rahe Mera Dil Film: Parichay with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Guide 31. -

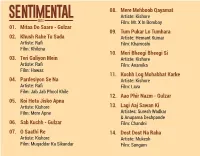

Sentimental Booklet for Web Copy

08. Mere Mehboob Qayamat Artiste: Kishore Film: Mr. X In Bombay 01. Mitaa Do Saare - Gulzar 09. Tum Pukar Lo Tumhara 02. Khush Rahe Tu Sada Artiste: Hemant Kumar Artiste: Rafi Film: Khamoshi Film: Khilona 10. Meri Bheegi Bheegi Si 03. Teri Galiyon Mein Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Rafi Film: Anamika Film: Hawas 11. Kuchh Log Mohabbat Karke 04. Pardesiyon Se Na Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Rafi Film: Lava Film: Jab Jab Phool Khile 12. Aao Phir Nazm - Gulzar 05. Koi Hota Jisko Apna Artiste: Kishore 13. Lagi Aaj Sawan Ki Film: Mere Apne Artistes: Suresh Wadkar & Anupama Deshpande 06. Sab Kuchh - Gulzar Film: Chandni 07. O Saathi Re 14. Dost Dost Na Raha Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Mukesh Film: Muqaddar Ka Sikandar Film: Sangam 2 3 15. Hui Sham Unka Khayal 22. Din Dhal Jaye Haye Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Film: Mere Hamdam Mere Dost Film: Guide 01. Mitaa Do Saare - Gulzar 16. Kuchh To Log Kahenge 23. Mere Toote Huye Dil Se 02. Khush Rahe Tu Sada Artiste: Kishore Artiste: Mukesh Artiste: Rafi Film: Amar Prem Film: Chhalia Film: Khilona 17. Waqt Karta Jo Wafa 24. Hue Hum Jinke Liye 03. Teri Galiyon Mein Artiste: Mukesh Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Film: Dil Ne Pukara Film: Deedar Film: Hawas 18. Patthar Ke Sanam 25. Koi Sagar Dil Ko Bahlata 04. Pardesiyon Se Na Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Rafi Film: Patthar Ke Sanam Film: Dil Diya Dard Liya Film: Jab Jab Phool Khile 19. Khilona Jan Kar Tum To 26. Chandi Ki Deewar 05. Koi Hota Jisko Apna Artiste: Rafi Artiste: Mukesh Artiste: Kishore Film: Khilona Film: Vishwas Film: Mere Apne 20. -

Copyright by Peter James Kvetko 2005

Copyright by Peter James Kvetko 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Peter James Kvetko certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Indipop: Producing Global Sounds and Local Meanings in Bombay Committee: Stephen Slawek, Supervisor ______________________________ Gerard Béhague ______________________________ Veit Erlmann ______________________________ Ward Keeler ______________________________ Herman Van Olphen Indipop: Producing Global Sounds and Local Meanings in Bombay by Peter James Kvetko, B.A.; M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2005 To Harold Ashenfelter and Amul Desai Preface A crowded, red double-decker bus pulls into the depot and comes to a rest amidst swirling dust and smoke. Its passengers slowly alight and begin to disperse into the muggy evening air. I step down from the bus and look left and right, trying to get my bearings. This is only my second day in Bombay and my first to venture out of the old city center and into the Northern suburbs. I approach a small circle of bus drivers and ticket takers, all clad in loose-fitting brown shirts and pants. They point me in the direction of my destination, the JVPD grounds, and I join the ranks of people marching west along a dusty, narrowing road. Before long, we are met by a colorful procession of drummers and dancers honoring the goddess Durga through thundering music and vigorous dance. The procession is met with little more than a few indifferent glances by tired workers walking home after a long day and grueling commute. -

Responses to 100 Best Acts Post-2009-10-11 (For Reference)

Bobbytalkscinema.Com Responses/ Comments on “100 Best Performances of Hindi Cinema” in the year 2009-10-11. submitted on 13 October 2009 bollywooddeewana bollywooddeewana.blogspot.com/ I can't help but feel you left out some important people, how about Manoj Kumar in Upkar or Shaheed (i haven't seen that) but he always made strong nationalistic movies rather than Sunny in Deol in Damini Meenakshi Sheshadri's performance in that film was great too, such a pity she didn't even earn a filmfare nomination for her performance, its said to be the reason on why she quit acting Also you left out Shammi Kappor (Junglee, Teesri MANZIL ETC), shammi oozed total energy and is one of my favourite actors from 60's bollywood Rati Agnihotri in Ek duuje ke Liye Mala Sinha in Aankhen Suchitra Sen in Aandhi Sanjeev Kumar in Aandhi Ashok Kumar in Mahal Mumtaz in Khilona Reena Roy in Nagin/aasha Sharmila in Aradhana Rajendra Kuamr in Kanoon Time wouldn't permit me to list all the other memorable ones, which is why i can never make a list like this bobbysing submitted on 13 October 2009 Hi, As I mentioned in my post, you are right that I may have missed out many important acts. And yes, I admit that out of the many names mentioned, some of them surely deserve a place among the best. So I have made some changes in the list as per your valuable suggestion. Manoj Kumar in Shaheed (Now Inlcuded in the Main 100) Meenakshi Sheshadri in Damini (Now Included in the Main 100) Shammi Kapoor in Teesri Manzil (Now Included in the Main 100) Sanjeev Kumar in Aandhi (Now Included in Worth Mentioning Performances) Sharmila Togore in Aradhana (Now Included in Worth Mentioning Performances) Sunny Deol in Damini (Shifted to More Worth Mentioning Performances) Mehmood in Pyar Kiye Ja (Shifted to More Worth Mentioning Performances) Nagarjun in Shiva (Shifted to More Worth Mentioning Performances) I hope you will approve the changes made as per your suggestions. -

Volume-15-Harmony-1458-Songs.Pdf

HINDI 1458 Song No Song Name Singer Movie/Album Song In 14131 Aa Aa Bhi Ja Lata Mangeshkar Tesri Kasam Volume-6 14039 Aa Dance Karen Thora Romance AshaKare Bhonsle Mohammed Rafi Khandan Volume-5 14208 Aa Ha Haa Naino Ke Kishore Kumar Hamaare Tumhare Volume-3 14041 Aa Ja Meri Jaan Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Jawab Volume-3 14042 Aa Ja Re Aa Ja Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Ankh Micholi Volume-3 13615 Aa Mere Humjoli Aa Lata Mangeshkar Mohammed RafJeene Ki Raah Volume-6 13616 Aa Meri Jaan Lata Mangeshkar Chandni Volume-6 12605 Aa Mohabbat Ki Basti BasayengeKishore Kumar Lata MangeshkarFareb Volume-3 13309 Aa Re Preetam Pyaare Sarosh Mamta Sharma Rowdy Rathore Volume-8 14209 Aage Se Dekho Peechhe Se Kishore Kumar Amit Kumar Ghazab Volume-3 14344 Aah Ko Chahiye Ghulam Ali Rooh E Ghazal Ghulam AliVolume-12 13618 Aai Baharon Ki Sham Mohammed Rafi Wapas Volume-4 14133 Aai Karke Singaar Lata Mangeshkar Do Anjaane Volume-6 13619 Aaina Hai Mera Chehra Lata Mangeshkar Asha Bhonsle SuAaina Volume-6 14506 Aaiye Barishon Ka Mausam Pankaj Udhas Chandi Jaisa Rang Hai TeraVolume-12 14043 Aaiye Huzoor Aaiye Na Asha Bhonsle Karmayogi Volume-5 14345 Aaj Ek Ajnabi Se Ashok Khosla Mulaqat Ashok Khosla Volume-12 13310 Aaj Hai Sagaai Abhijeet Alkaji Pyaar To Hona Hi Tha Volume-8 14346 Aaj Hum Bichade Hai Jagjit Singh Love Is Blind Volume-12 12404 Aaj Is Darja Pila Do Ki Mohammed Rafi Vaasana Volume-4 14436 Aaj Kal Shauqe Deedar Hai Asha Bhosle Mohammed Rafi Leader Volume-5 14044 Aaj Khushi Se Jhum Raha Sara Asha Bhonsle Suntan Volume-5 14437 Aaj Ki Raat Mohammed -

Alphabetical List of Recommendations Received for Padma Awards - 2014

Alphabetical List of recommendations received for Padma Awards - 2014 Sl. No. Name Recommending Authority 1. Shri Manoj Tibrewal Aakash Shri Sriprakash Jaiswal, Minister of Coal, Govt. of India. 2. Dr. (Smt.) Durga Pathak Aarti 1.Dr. Raman Singh, Chief Minister, Govt. of Chhattisgarh. 2.Shri Madhusudan Yadav, MP, Lok Sabha. 3.Shri Motilal Vora, MP, Rajya Sabha. 4.Shri Nand Kumar Saay, MP, Rajya Sabha. 5.Shri Nirmal Kumar Richhariya, Raipur, Chhattisgarh. 6.Shri N.K. Richarya, Chhattisgarh. 3. Dr. Naheed Abidi Dr. Karan Singh, MP, Rajya Sabha & Padma Vibhushan awardee. 4. Dr. Thomas Abraham Shri Inder Singh, Chairman, Global Organization of People Indian Origin, USA. 5. Dr. Yash Pal Abrol Prof. M.S. Swaminathan, Padma Vibhushan awardee. 6. Shri S.K. Acharigi Self 7. Dr. Subrat Kumar Acharya Padma Award Committee. 8. Shri Achintya Kumar Acharya Self 9. Dr. Hariram Acharya Government of Rajasthan. 10. Guru Shashadhar Acharya Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India. 11. Shri Somnath Adhikary Self 12. Dr. Sunkara Venkata Adinarayana Rao Shri Ganta Srinivasa Rao, Minister for Infrastructure & Investments, Ports, Airporst & Natural Gas, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh. 13. Prof. S.H. Advani Dr. S.K. Rana, Consultant Cardiologist & Physician, Kolkata. 14. Shri Vikas Agarwal Self 15. Prof. Amar Agarwal Shri M. Anandan, MP, Lok Sabha. 16. Shri Apoorv Agarwal 1.Shri Praveen Singh Aron, MP, Lok Sabha. 2.Dr. Arun Kumar Saxena, MLA, Uttar Pradesh. 17. Shri Uttam Prakash Agarwal Dr. Deepak K. Tempe, Dean, Maulana Azad Medical College. 18. Dr. Shekhar Agarwal 1.Dr. Ashok Kumar Walia, Minister of Health & Family Welfare, Higher Education & TTE, Skill Mission/Labour, Irrigation & Floods Control, Govt. -

Marhowrah Factory Branch, Chapra Is Outstanding for the Year 1994-95

135 Written Answers JULY 19, 1996 Written Answers 136 Marhowrah Factory Branch, Chapra is outstanding for STATEMENT the year 1994-95 and 1995-96; (b) if so, the details thereof. S No Name of the film artists, directors & producers (c) the time by which the outstanding payment are 1 2 likely to be made to the farmers7 Amitabh Bachchan THE MINISTER OF TEXTILES (SHRI R.L. JALAPPA). 1. Shri (a) to (c) The Cawnpore Sugar Works Limited have 2 Shri Ashok Ghai intimated that as on 8th July. 1996 the Marhowrah Sugar 3. Shri Subhash Ghai Factory Branch. Chapra has cane price arrears of Rs. 4 M/s. Mukta Arts (P) Ltd 61.52 lakhs and Rs 361 49 lakhs for 1994-95 season 5, M/s. Daulat Theatre and 1995-96 season respectively. 6. Shri DM Netrawala The Company has been declared sick by the BIFR 7. Hiba Films (P) Ltd. On account of liquidity crunch, timely payment of M/s. outstanding dues to the farmers has not been possible 8 Shri Jagdish Sidana The Company, however, is making efforts to clear the 9. M/s. Milgrey Studio Research lab (P) Ltd. outstandings as far as possible 10 Shri Raja Roy 1 1 Shri Sunil Hingorani income Tax Dues 12. Shri U N Singh 1194 SHRI RADHA MOHAN SINGH ; Will the 13. Shri Laxmikant Berde Minister of FINANCE be pleased to state 14. Shri S P. Chaudhary (a) the names of film artists, directors, producers 15. Shri Bappi Lahiri who owe income-tax'wealth-tax exceeding rupee one 16. -

Inauguration of Rajkot Voluntary Blood Bank & Research Centre by Mr

1981 Inauguration of RVBB & RC: Inauguration of Rajkot Voluntary Blood Bank & Research Centre by Mr. Peter Rogerson & Smt. Leela Moolgaokar : 6th December 1981 1982 Bharat-ratna Mother Teresa Mother Teresa showered blessings on her visit of RVBB & RC 25th February 1982 1982 Smt. Sharda Mukharjee – Governor of Gujarat at RVBB & RC 19th October 1982. 1982 Reflections by the legendary star Dilip Kumar 15th August 1982 1983 Renowned Indian cricketer Mr. Kapil Dev at RVBB & RC 3rd September 1983 1984 Dr. K. H. Chhaya, Medical Director, RVBB & RC from India selected by British Council – for attending a training in Scotland, UK to study Blood Transfusion, Medicine along with 50 participants from 26 countries 1984 Shri Darbari Seth, Chairman & Managing Director of Tata Chemicals Ltd. & Tata Tea Ltd. 8th December 1984. 1984 Reflections by Shri Darbari Seth 8th December 1984. 1985 Governing Council meeting at Mumbai attended by Chief Patron Shri Darbari Seth, Founder Chairperson Smt. Leela Moolgaokar, Shri Harshadbhai Mehta and Shri Chandrakant Koticha. On 24th Julay 1985. 1985 Accreditation from AABB RVBB & RC was honored as a first member from India by American Association of Blood Banks in 1983 & got accreditation on 25th September 1985 1986 An agreement signed with World Health Organization (WHO) to frame the ‘Technical and Administrative Standards in blood banking and transfusion services in India’. 1986 Late Rajeev Gandhi inaugurated 1st computerised MIS Blood Bank in India. He inaugurated first MIS software repared by TCS : 1986. Here is a rare memorable picture of late Rajeev Gandhi - the then Prime Minister of India - donating blood. 1986 Late Rajeev Gandhi inaugurated 1st computerised MIS Blood Bank in India. -

Volume-16-Symphony-Songs-1132.Pdf

HINDI 1132 Song No Song Name Singer Movie/Album Song In 14131 Aa Aa Bhi Ja Lata Mangeshkar Tesri Kasam Volume-6 14039 Aa Dance Karen Thora Romance AshaKare Bhonsle Mohammed Rafi Khandan Volume-5 14208 Aa Ha Haa Naino Ke Kishore Kumar Hamaare Tumhare Volume-3 14041 Aa Ja Meri Jaan Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Jawab Volume-3 14042 Aa Ja Re Aa Ja Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Ankh Micholi Volume-3 13615 Aa Mere Humjoli Aa Lata Mangeshkar Mohammed RafJeene Ki Raah Volume-6 13616 Aa Meri Jaan Lata Mangeshkar Chandni Volume-6 12605 Aa Mohabbat Ki Basti BasayengeKishore Kumar Lata MangeshkarFareb Volume-3 14209 Aage Se Dekho Peechhe Se Kishore Kumar Amit Kumar Ghazab Volume-3 14344 Aah Ko Chahiye Ghulam Ali Rooh E Ghazal Ghulam AliVolume-12 13618 Aai Baharon Ki Sham Mohammed Rafi Wapas Volume-4 14133 Aai Karke Singaar Lata Mangeshkar Do Anjaane Volume-6 13619 Aaina Hai Mera Chehra Lata Mangeshkar Asha Bhonsle SuAaina Volume-6 14506 Aaiye Barishon Ka Mausam Pankaj Udhas Chandi Jaisa Rang Hai TeraVolume-12 14043 Aaiye Huzoor Aaiye Na Asha Bhonsle Karmayogi Volume-5 14345 Aaj Ek Ajnabi Se Ashok Khosla Mulaqat Ashok Khosla Volume-12 14346 Aaj Hum Bichade Hai Jagjit Singh Love Is Blind Volume-12 12404 Aaj Is Darja Pila Do Ki Mohammed Rafi Vaasana Volume-4 14436 Aaj Kal Shauqe Deedar Hai Asha Bhosle Mohammed Rafi Leader Volume-5 14044 Aaj Khushi Se Jhum Raha Sara Asha Bhonsle Suntan Volume-5 14437 Aaj Ki Raat Mohammed Rafi Asha Bhosle Nai Umar Ki Nai Fasal Volume-4 12203 Aaj Koi Pyar Se Asha Bhonsle Sawan Ki Ghata Volume-5 13622 Aaj Main Jawan Ho Gai Hoon -

1St Filmfare Awards 1953

FILMFARE NOMINEES AND WINNER FILMFARE NOMINEES AND WINNER................................................................................ 1 1st Filmfare Awards 1953.......................................................................................................... 3 2nd Filmfare Awards 1954......................................................................................................... 3 3rd Filmfare Awards 1955 ......................................................................................................... 4 4th Filmfare Awards 1956.......................................................................................................... 5 5th Filmfare Awards 1957.......................................................................................................... 6 6th Filmfare Awards 1958.......................................................................................................... 7 7th Filmfare Awards 1959.......................................................................................................... 9 8th Filmfare Awards 1960........................................................................................................ 11 9th Filmfare Awards 1961........................................................................................................ 13 10th Filmfare Awards 1962...................................................................................................... 15 11st Filmfare Awards 1963.....................................................................................................