Temporal and Kinematic Gait Variables of Thoroughbred Racehorses at Or Near Racing Speeds Jeffrey A.Seder, AB, JD, MBA, and Charles E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

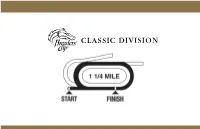

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

Mating Analysis West Coast

MATING ANALYSIS You may submit your mare online at lanesend.com or call 859-873-7300 to discuss your matings with CHANCE TIMM, [email protected], JILL MCCULLY, [email protected] or LEVANA CAPRIA, [email protected]. WEST COAST Flatter – Caressing by Honour and Glory 2014 Bay l 16.2 Hands “An Eclipse Award winning champion, West Coast is by an outstanding sire son of A.P. Indy, out of a ChampionTwo-Year-Old Filly. West Coast earned a title as Champion Three-Year-Old Colt with five consecutive victories, four in stakes events, and ran 1-2-3 in six consecutive grade one events, including when capturing the Travers Stakes (G1) and Pennsylvania Derby (G1). He is by Flatter, a leading stallion son of A.P. Indy, and sire of more than 50 stakes winners, and out of Caressing, Champion and Breeders’ Cup (G1) winner at two.“ The offspring of West Coast will be free of Northern Dancer at four generations on their sire’s side, and Flatter has crossed well with a wide variety of broodmare sires from that line. The cross with mares from the Danzig branch of Northern Dancer has been particulary productive with seven stakes winners, including graded stakes winners Classic Point and Mad Flatter out of mares by Langfuhr and Honor Grades (who gives inbreeding to the dam of A.P. Indy), and there are also stakes winners out of mares by War Front – who appears particularly interesting here, giving inbreeding to Relaunch and a full-sister – Danzig Connection, Ghazi and Military (who would be intriguing here). -

Analysis and Characterization of the Normal Gait Phases of Walking

Pesq. Vet. Bras. 38(3):536-543, março 2018 DOI: 10.1590/1678-5150-PVB-4496 Vet 2506 pvb-4496 LD Analysis and characterization of the normal gait phases of walking Warmblood horses as a tool for the diagnosis of lameness1 2 2 2 3 Lázaro Morales-Acosta *, Armando Ortiz-Prado , Víctor H. Jacobo-Armendáriz ABSTRACT.- and Raide A. González-Carbonell Analysis and characterization of the normal gait phases of walking Warmblood horses as a tool Morales-Acosta for the diagnosis L., Ortiz-Prado of lameness. A., Jacobo-Armendáriz Pesquisa Veterinária V.H. Brasileira & González-Carbonell 38(3):536-543. R.A. 2018. Unidad de Investigación y Asistencia Técnica en Materiales, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Coyoacán, Distrito Federal, 04510, México. E-mail: [email protected] Horses with lameness modify gait behavior, but when it is subtle, it may not be possible to identify it clinically. The objective of this research is to characterize the normal gait phases of walking Warmblood horses by combining photogrammetry and accelerometry to monitor lameness to indicate a structural or functional disorder in the extremities. The study was conducted in 23 adult male Warmblood horses. Photogrammetry was used to identify the kinematic variables of the limbs and the markers path over time; triaxial accelerometers were used to capture the orthogonal acceleration components. It was determined that only 10 horses showed a normal gait pattern, there was a 43% correspondence between the expert´s judgment and the diagnostic techniques. According to the Stashak classification of the gait phases, cycle phases to forelimb were 34/4/8/13/41, while for hind limb were 54/11/8/8/19 (% of the stride). -

MJC Media Guide

2021 MEDIA GUIDE 2021 PIMLICO/LAUREL MEDIA GUIDE Table of Contents Staff Directory & Bios . 2-4 Maryland Jockey Club History . 5-22 2020 In Review . 23-27 Trainers . 28-54 Jockeys . 55-74 Graded Stakes Races . 75-92 Maryland Million . 91-92 Credits Racing Dates Editor LAUREL PARK . January 1 - March 21 David Joseph LAUREL PARK . April 8 - May 2 Phil Janack PIMLICO . May 6 - May 31 LAUREL PARK . .. June 4 - August 22 Contributors Clayton Beck LAUREL PARK . .. September 10 - December 31 Photographs Jim McCue Special Events Jim Duley BLACK-EYED SUSAN DAY . Friday, May 14, 2021 Matt Ryb PREAKNESS DAY . Saturday, May 15, 2021 (Cover photo) MARYLAND MILLION DAY . Saturday, October 23, 2021 Racing dates are subject to change . Media Relations Contacts 301-725-0400 Statistics and charts provided by Equibase and The Daily David Joseph, x5461 Racing Form . Copyright © 2017 Vice President of Communications/Media reproduced with permission of copyright owners . Dave Rodman, Track Announcer x5530 Keith Feustle, Handicapper x5541 Jim McCue, Track Photographer x5529 Mission Statement The Maryland Jockey Club is dedicated to presenting the great sport of Thoroughbred racing as the centerpiece of a high-quality entertainment experience providing fun and excitement in an inviting and friendly atmosphere for people of all ages . 1 THE MARYLAND JOCKEY CLUB Laurel Racing Assoc. Inc. • P.O. Box 130 •Laurel, Maryland 20725 301-725-0400 • www.laurelpark.com EXECUTIVE OFFICIALS STATE OF MARYLAND Sal Sinatra President and General Manager Lawrence J. Hogan, Jr., Governor Douglas J. Illig Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Tim Luzius Senior Vice President and Assistant General Manager Boyd K. -

Brown Brigade Blows Through the Windy City

SUNDAY, AUGUST 11, 2019 F-T NEW YORK BRED SALE STARTS SUNDAY BROWN BRIGADE BLOWS by Jessica Martini THROUGH THE WINDY CITY SARATOGA SPRINGS, NY - Action returns to the Humphrey S. Finney Pavilion Sunday evening with the first of two sessions of the Fasig-Tipton New York-Bred Yearlings Sale in Saratoga. The auction, which gets underway at 7 p.m., comes four days after Fasig-Tipton=s record-setting Saratoga Select Sale, and will look to follow up on back-to-back record-setting renewals of its own. The New York sale set highwater marks for gross, median and average, as well as top price, in both 2017 and 2018 as the state=s breeders, supported by high purses and breeders= incentive awards, continue to improve the quality of their stock. AThis is definitely the best group we=ve ever brought here,@ Derek MacKenzie said as he oversaw his 18-horse Vinery Sales consignment Saturday morning. AI say that every year and every year it=s true.@ Cont. p5 Bricks and Mortar made Chad Brown the winningest trainer IN TDN EUROPE TODAY in Arlington Million history Saturday | Coady KING KAMEHAMEHA DIES AT 18 by Alan Carasso MG1SW and successful sire King Kamehameha (Jpn) It would appear that trainer Chad Brown finally has this thing (Kingmambo) passed away at 18 in Japan. Click or tap here to figured out. go straight to TDN Europe. The New York-based conditioner had managed to win two of the three Grade I events comprising Arlington=s International Festival of Racing--the Arlington Million, the Beverly D. -

Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’S Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes

Northern Dancer 90th May 2, 1964 THE WINNER’S PEDIGREE AND CAREER HIGHLIGHTS Pharos Nearco Nogara Nearctic *Lady Angela Hyperion NORTHERN DANCER Sister Sarah Polynesian Bay Colt Native Dancer Geisha Natalma Almahmoud *Mahmoud Arbitrator YEAR AGE STS. 1ST 2ND 3RD EARNINGS 1963 2 9 7 2 0 $ 90,635 1964 3 9 7 0 2 $490,012 TOTALS 18 14 2 2 $580,647 At 2 Years WON Summer Stakes, Coronation Futurity, Carleton Stakes, Remsen Stakes 2ND Vandal Stakes, Cup and Saucer Stakes At 3 Years WON Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’s Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes Horse Eq. Wt. PP 1/4 1/2 3/4 MILE STR. FIN. Jockey Owner Odds To $1 Northern Dancer b 126 7 7 2-1/2 6 hd 6 2 1 hd 1 2 1 nk W. Hartack Windfields Farm 3.40 Hill Rise 126 11 6 1-1/2 7 2-1/2 8 hd 4 hd 2 1-1/2 2 3-1/4 W. Shoemaker El Peco Ranch 1.40 The Scoundrel b 126 6 3 1/2 4 hd 3 1 2 1 3 2 3 no M. Ycaza R. C. Ellsworth 6.00 Roman Brother 126 12 9 2 9 1/2 9 2 6 2 4 1/2 4 nk W. Chambers Harbor View Farm 30.60 Quadrangle b 126 2 5 1 5 1-1/2 4 hd 5 1-1/2 5 1 5 3 R. Ussery Rokeby Stables 5.30 Mr. Brick 126 1 2 3 1 1/2 1 1/2 3 1 6 3 6 3/4 I. -

Double and Triple Fully Airborne Phases in the Gaits of Racing Speed Thoroughbreds Jeffrey A

Double and Triple Fully Airborne Phases in the Gaits of Racing Speed Thoroughbreds Jeffrey A. Seder, AB, JD, MBA, and Charles E. Vickery, III, BS INTRODUCTION tary gallop, often seen in a horse coming out of the starting Current literature suggests that during the gallop, there gate. The rotary gallop is generally seen in the counter- is normally one airborne phase during a single stride,1,2 be- clock wise direction of LR, RR, RF, LF, and, unlike the ginning when the lead foreleg leaves the ground and ending switching of leads, the rotary gallop is often repeated for when the non-lead rear leg bears weight. During a normal more than one stride. transverse gallop stride pattern, the following step sequence This study documents the frequency of occurrence of occurs. Sequence numbers with corresponding occurrences additional airborne phases within a single stride between include: the lead rear leg and non-lead foreleg and between the 1. Left rear leg (LR) bears weight. This leg would be forelegs (these air phases respectively referred to as “dou- considered the non-lead rear leg of a horse on its ble-air-P2” and “double-air-P3”). right lead. We refer to horses that used more than one airborne 2. A few hundredths of a second before the left rear leg phase within a single stride as “double-air” horses. We refer stops bearing weight, the right rear leg (RR) bears to horses that used 3 airborne phases within a single stride weight. In this instance, the right rear leg is called the as “triple-air” horses. -

128 CALIFORNIA THOROUGHBRED 2016 STALLION DIRECTORY ❙ Check Daily Updates on Stallionregister.Com

MINISTERS WILD CAT b, 2000 height 16.2 Dosage (6-1-10-1-0); DI: 2.00; CD: 0.67 See gray pages—Nearctic RACE AND (STAKES) RECORD Northern Dancer, 1961 Nearctic, by Nearco Age Starts 1st 2nd 3rd Earned 18s, SW, $580,647 2 1 0 1 0 $9,600 Vice Regent, 1967 636 f, 147 SW, 5.10 AEI Natalma, by Native Dancer 3 6 2(1) 2(2) 0 $134,400 5s, wnr, $6,215 Victoria Regina, 1958 Menetrier, by Fair Copy 4 9 1 2 1 $73,072 673 f, 105 SW, 2.89 AEI Deputy Minister, dkb/br, 1979 26s, SW, $45,480 5 6 3(1) 0 1(1) $151,657 22s, SW, $696,964 3 f, 3 r, 3 w, 1 SW Victoriana, by Windfields Totals 22 6(2) 5(2) 2(1) $368,729 1,142 f, 90 SW, 2.52 AEI Bunty's Flight, 1953 Bunty Lawless, by Ladder 7.77 AWD Won At 3 43s, SW, $42,300 Mint Copy, 1970 104 f, 3 SW, 0.79 AEI Broomflight, by Deil Golden State Mile S ($78,650, 8f in 1:36.89, dftg. 76s, wnr, $53,945 Winning Stripes, Clover Situation, Es Special, Always 7 f, 7 r, 4 w, 1 SW Shakney, 1964 Jabneh, by Bimelech Remember, Natural Balance, Demon Warlock). 8s, unpl Grass Shack, by Polynesian A maiden special weight race at SA ($62,400, 7f). 11 f, 11 r, 8 w, 1 SW 2nd El Camino Real Derby (gr. III, 8.5f, to Ocean Roberto, 1969 Hail to Reason, by Turn-to Terrace, dftg. -

138904 03 Dirtmile.Pdf

breeders’ cup dirt mile BREEDERs’ Cup DIRT MILE (GR. I) 7th Running Santa Anita Park $1,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS AND UPWARD ONE MILE Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 123 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 120 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $1 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Dirt Mile will be limited to twelve (12). If more than twelve (12) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge Winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Friday, November 1, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Dirt Mile (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Alpha Godolphin Racing, LLC Lessee Kiaran P. McLaughlin B.c.4 Bernardini - Munnaya by Nijinsky II - Bred in Kentucky by Darley Broadway Empire Randy Howg, Bob Butz, Fouad El Kardy & Rick Running Rabbit Robertino Diodoro B.g.3 Empire Maker - Broadway Hoofer by Belong to Me - Bred in Kentucky by Mercedes Stables LLC Brujo de Olleros (BRZ) Team Valor International & Richard Santulli Richard C. -

Eclipse Special Edition

Gamine Gives Sire A Second Winner... 'TDN Rising Star' Essential Quality (Tapit) did his part, ripping Michael Lund's 'TDN Rising Star' Gamine (Into Mischief) was through his competition in three starts and clinching the Eclipse something of a lightning rod in 2020, but she possessed arguably Award as champion 2-year-old male with a sizzling finish in the the most raw ability of any horse in training and while she GI Breeders' Cup Juvenile. Monomoy Girl (Tapizar) won her finished a distant runner-up to Swiss Skydiver in the 3-year-old second Eclipse Award in the last three years, adding to her filly category, she easily 3-year-old filly championship outdistanced Serengeti with the 2020 Eclipse as Empress (Alternation) to take champion older female. home the Eclipse for champion Purchased by Spendthrift for female sprinter. The $220,000 $9.5 million at Fasig-Tipton Keeneland September yearling November, the chestnut is turned $1.8-million Fasig- nearing her 6-year-old debut. Tipton Midlantic topper Other Wide-Margin became the second straight daughter of Into Mischief to Winners... both win the GI Breeders' Cup Vequist (Nyquist) provided Filly & Mare Sprint en route to her sire from his very first crop a championship following on to the races, securing the the exploits of Covfefe in 2019. Eclipse as champion 2-year-old Trainer Bob Baffert had his filly on the strength of hands on a third Eclipse winner victories in the GI Spinaway S. for 2020 in the form of 'TDN Gamine | Sarah Andrew in September before turning Rising Star' Improbable (City Zip). -

Ns National Show Horse Division

CHAPTER NS NATIONAL SHOW HORSE DIVISION SUBCHAPTER NS-1 GENERAL QUALIFICATIONS NS101 Eligibility NS102 Shoeing Regulations NS103 Boots NS104 Breed Standard NS105 General NS106 Division of Classes NS107 Conduct NS108 Judging Criteria NS109 Qualifying Classes and Specifications NS110 Division of Classes SUBCHAPTER NS-2 DESCRIPTION OF GAITS NS111 General NS112 Walk NS113 Trot NS114 Canter NS115 Slow Gait NS116 Rack NS117 Hand Gallop SUBCHAPTER NS-3 HALTER CLASSES NS118 General NS119 Get of Sire and Produce of Dam SUBCHAPTER NS-4 PLEASURE SECTION NS120 English Pleasure, Country Pleasure and Classic Country Pleasure Amateur Owner to Show Appointments NS121 Pleasure Driving and Country Pleasure Driving Appointments NS122 English Pleasure Description NS123 English Pleasure Gait Requirements NS124 English Pleasure Classes and Specifications NS125 Country Pleasure Description NS126 Country Pleasure Gait Requirements NS127 Country Pleasure Judging Requirements NS128 Country Pleasure Classes and Specifications NS129 Pleasure Driving Gait Requirements NS130 Pleasure Driving Judging Requirements NS131 Pleasure Driving Class Specifications NS132 Classic Country Pleasure Amateur Owner To Show © USEF 2021 NS - 1 NS133 Classic Country Pleasure Amateur Owner to Show Gait Requirements NS134 Classic Country Pleasure Amateur Owner to Show Judging Requirements SUBCHAPTER NS-5 FINE HARNESS SECTION NS135 General NS136 Appointments NS137 Gait Requirements NS138 Line Up NS139 Ring Attendants NS140 Class Specifications SUBCHAPTER NS-6 FIVE GAITED SECTION NS141 Appointments -

HEADLINE NEWS This November, Think

POSSE to Vinery Kafwain to Jonabell HEADLINE p. 2 NEWS For information about TDN, DELIVERED EACH NIGHT call 732-747-8060. BY FAX AND INTERNET www.thoroughbreddailynews.com WEDNESDAY, JULY 23, 2003 SCHUYLERVILLE STARTS SPA SPECTACULAR FERDINAND LIKELY SLAUGHTERED IN JAPAN Racing returns to historic Saratoga for the 135th time Kentucky Derby winner Ferdinand (Nijinsky II--Banja today and the action will heat up quickly with a field of Luka, by Double Jay) has apparently been slaughtered eight juvenile fillies set to go postward in the GII in Japan, The Blood-Horse’s Barbara Bayer reported. Schuylerville S. The six- Ferdinand became the first Derby winner for legendary furlong contest is trainer Charlie Whittingham when he won the Run for headed by 5-2 morning- the Roses in 1986 and he was the final Derby winner in line favorite Hermione’s the historic career of jockey Bill Shoemaker. In 1987, Magic (Forest Wildcat). Ferdinand was named champion older horse and Horse The Todd Pletcher of the Year after defeating fellow Derby winner Alysheba trainee was an impres- in a thrilling renewal of the Breeders’ Cup Classic. He sive six-length winner was retired to Claiborne Farm, standing his initial sea- of her debut at Belmont son in 1989 for $30,000. Among his limited success as in June. “She’s ex- a stallion was GI Florida Derby winner Bull Inthe tremely quick; she’s go Heather and graded stakes Saratoga Horsephotos go go, all the time,” winner Bibury Court. Ferdinand said jockey John was sold to Japan’s JS Com- Velazquez, who rides the filly in an attempt to win his pany in the fall of 1994 and he second straight Schulyerville.