Vulnerability to Bushfires in Rural Australia: a Case Study from East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Submission To: Victorian Bushfire Inquiry

Submission to: Victorian Bushfire Inquiry Addressed to: Tony Pearce; Inspector-General Emergency Management, Victoria Submission from: Emergency Leaders for Climate Action https://emergencyleadersforclimateaction.org.au/ Prepared on behalf of ELCA by: Greg Mullins AO, AFSM; Former Commissioner, Fire & Rescue NSW May 2020 1 About Emergency Leaders for Climate Action Climate change is escalating Australia’s bushfire threat placing life, property, the economy and environment at increasing risk. Emergency Leaders for Climate Action (ELCA) was formed in April 2019 due to deep shared concerns about the potential of the 2019/20 bushfire season, unequivocal scientific evidence that climate change is the driver of longer, more frequent, more intense and overlapping bushfire seasons, and the failure of successive governments, at all levels, to take credible, urgent action on the basic causal factor: greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of coal, oil and gas. Greenhouse emissions are causing significant warming, in turn worsening the frequency and severity of extreme weather events that exacerbate and drive natural disasters such as bushfires. ELCA originally comprised of 23 former fire and emergency service leaders from every state and territory and every fire service in Australia, from several State Emergency Service agencies, and from several forestry and national parks agencies. At the time of submission, ELCA continues to grow and now comprises 33 members, including two former Directors General of Emergency Management Australia. Cumulatively, ELCA represents about 1,000 years of experience. Key members from Victoria include: • Craig Lapsley PSM: Former Emergency Management Commissioner; Former Fire Services Commissioner; Former Deputy Chief Officer, Country Fire Authority. • Russell Rees AFSM: Former Chief Fire Officer, Country Fire Authority Victoria. -

Gippsland Bushfire Management Strategy 2020

Gippsland Bushfire Management Strategy 2020 Fuel management Bushfire Risk Engagement Areas Prevention of human-caused ignition strategy (pilot) First-attack suppression strategy (pilot) Acknowledgements We acknowledge and respect Victoria’s Traditional Owners as the original custodians of the state’s land and waters, their unique ability to care for Country and deep spiritual connection to it. We honour Elders past and present, whose knowledge and wisdom has ensured the continuation of culture and traditional practices. We are committed to genuinely partner and meaningfully engage with Victoria’s Traditional Owners and Aboriginal communities to support the protection of Country, the maintenance of spiritual and cultural practices and their broader aspirations in the 21st century and beyond. We thank our colleagues and partners in the Gippsland Safer Together Executive Team, Gippsland Regional Strategic Fire Management Planning Committee and Gippsland Strategic Bushfire Management Planning Working Group for their support developing the strategy. We would like to acknowledge all the workshop participants and the agencies who provided staff to attend each session for their contributions to the working group. We would also like to acknowledge those who participated in the Engage Victoria surveys for their comments. Authors Prepared by members of the Gippsland Strategic Bushfire Management Planning Working Group. Analysis was undertaken by the Risk and Evaluation Team, Gippsland. Aboriginal people should be aware that this publication may contain images or names of deceased persons in photographs or printed material. Photo credits Risk and Evaluation Team, Gippsland © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2020 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. -

Bushfires in Our History, 18512009

Bushfires in Our History, 18512009 Area covered Date Nickname Location Deaths Losses General (hectares) Victoria Portland, Plenty 6 February Black Ranges, Westernport, 12 1 million sheep 5,000,000 1851 Thursday Wimmera, Dandenong 1 February Red Victoria 12 >2000 buildings 260,000 1898 Tuesday South Gippsland These fires raged across Gippsland throughout 14 Feb and into Black Victoria 31 February March, killing Sunday Warburton 1926 61 people & causing much damage to farms, homes and forests Many pine plantations lost; fire New South Wales Dec 1938‐ began in NSW Snowy Mts, Dubbo, 13 Many houses 73,000 Jan 1939 and became a Lugarno, Canberra 72 km fire front in Canberra Fires Victoria widespread Throughout the state from – Noojee, Woods December Point, Omeo, 1300 buildings 13 January 71 1938 Black Friday Warrandyte, Yarra Town of Narbethong 1,520,000 1939 January 1939; Glen, Warburton, destroyed many forests Dromona, Mansfield, and 69 timber Otway & Grampian mills Ranges destroyed Fire burnt on Victoria 22 buildings 34 March 1 a 96 km front Hamilton, South 2 farms 1942 at Yarram, Sth Gippsland 100 sheep Gippsland Thousands 22 Victoria of acres of December 10 Wangaratta grass 1943 country Plant works, 14 Victoria coal mine & January‐ Central & Western 32 700 homes buildings 14 Districts, esp >1,000,000 Huge stock losses destroyed at February Hamilton, Dunkeld, Morwell, 1944 Skipton, Lake Bolac Yallourn ACT 1 Molongolo Valley, Mt 2 houses December Stromlo, Red Hill, 2 40 farm buildings 10,000 1951 Woden Valley, Observatory buildings Tuggeranong, Mugga ©Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority, State Government of Victoria, 2011, except where indicated otherwise. -

Cold-Frontal Bushfire Winds and Computer Forecast Models

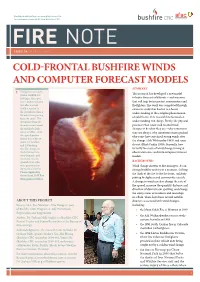

ISSUE 54 MARCH 2010 COld-frONTAL BUSHFIRE WINDS AND COMPUTER FORECAST MODELS SUMMARY This photo was taken This research has developed a new model from a Firebird 303 JetRanger helicopter to better forecast cold fronts – and outcome over Lawloit, Victoria, that will help better protect communities and just after a recent firefighters. The work was completed through wildfire was hit by extensive study that has led to a better the downburst from a understanding of the complex phenomenon thunderstorm passing of cold fronts. This research has focused on by to the south. The downburst from the understanding two things. Firstly, the physical thunderstorm turned processes that cause cold-frontal wind the northerly flank changes to be what they are – why sometimes into a headfire - with they are abrupt, why sometimes more gradual, the typical pattern why some have sustained strong winds after from a line of fire of the change (Ash Wednesday 1983) and some about 5/6 headfire and 1/6 backing do not (Black Friday 1939). Secondly, how fire. The change in to verify forecasts of wind change timing at fire behaviour was observation sites and from computer forecast very dramatic, and models. increased risks to ground crews who BACKGROUND were positioned to Wind change matters to fire managers. It can the north of the fire. change bushfire activity in a moment, shifting Photo supplied by the flank of the fire to the fire front, suddenly Steve Grant, DSE Fire Management Officer. putting firefighters and communities at risk. A change in wind can also change the rate of fire spread, increase the quantity, distance and direction of downstream spotting, and change the safety status of residents and townships in a flash. -

Fire in the Victorian Environment Balancing Threats with Necessities

Fire in the Victorian Environment Balancing threats with necessities www.ces.vic.gov.au December 2008 Fact Sheet No.10 This fact sheet is one of a series, developed from material presented in Victoria’s first comprehensive State of the Environment Report. The Report is a major undertaking of the Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability and covers a broad range of environmental issues affecting the State. Its purpose is to improve community understanding of Victoria’s environment, and through the use of recommendations, to enhance its condition for present and future generations. The report was released in December 2008 and is available at www.ces.vic.gov.au Key Findings Planned and unplanned fire in Victoria • Climate change is forecast to increase the number of very Fire is one of the tools used by the Department of Sustainability high or extreme fire danger days across south-eastern and Environment to manage Victoria’s 8.9 million hectares of Australia by up to 25% by 2020 and up to 230% by 2050. public land. Planned fire is used to manipulate fuel loads and • Victoria has experienced frequent and severe fires in the last to achieve ecological outcomes, such as desirable vegetation decade, including major bushfires in 2003 and 2007 that composition and structure. each burnt more than 1 million hectares. • Some species have undergone marked declines and have lost Since 2001, about 4.7% of Victoria’s remaining native vegetation large amounts of habitat following these large-scale fires. has been burnt in planned fire events. In most years the area • Inappropriate fire regimes (too much or too little fire) burnt has been in the range 20,000–75,000 hectares, but in threaten the persistence and condition of some species and 2004 and 2005 over 100,000 hectares were burnt in response to ecosystems. -

Victoria's Bushfire Strategy

S WIT.005.001.1776 f i ; p - 11 --. -. S ______ A significant .5.-.'- Living change in the way -a.. government and Victorians with Fire manage fire is required to meet future -S.- Victoria’s Bushfire bushfire Strategy challenges wr: R,Aril ,it AL. A. P WIT.005.001.1777 E110 Published by the Victorian Government Melbourne, June 2008 © The State of Victoria 2008 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne ISBN 978-1-74208-673-6 (print) ISBN 978-1-74208-674-3 (PDF) For more information contact the Department of Sustainability & Environment Customer Service Centre 136 186 Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw PHOTOS: of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your FRONT COVER MAIN PHOTO: DSE; particular purposes and therefore disclaims all OTHER PHOTOS CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT – liability for any error, loss or other consequence DSE; HAYDEN BRIGGS/STATE AIRCRAFT UNIT; which may arise from you relying on any LAUREN BUTTERFIELD/DSE; DSE; KATHRYN LITTLE/DSE; information in this publication. GEOFF DEACON/CFA; RACHEL DAWKIN/DSE; CFA. Accessibility THIS PAGE: MAIN PHOTO – DSE; If you would like to receive this publication in an OTHER PHOTOS LEFt to right – KATHY OVERTON/ accessible format, such as large print or audio, DSE; DSE; DSE. please telephone 138 186, 1800 122 969 (TTY), or email [email protected] Except where noted, CFA photos courtesy of CFA This document is also available in nPDF 0 format on photo library and Keith Pakenham (CFA Image the Internet at www.dse.vic.gov.au Specialist). -

Air Quality During the 2006–07 Victorian Bushfires

ENVIRONMENT REPORT – VICTORIA’S CHANGING ENVIRONMENT AIR QUALITY DURING THE 2006–07 VICTORIAN BUSHFIRES Publication 1187 December 2007 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Bushfires impact on air quality and human health. making informed decisions to protect their health on Victoria is one of the most fire-prone regions in the smoke-affected days. world — approximately 1.2 million hectares were burnt Prevailing winds and fire conditions meant that a large during the major bushfires between December 2006 area of Victoria was impacted by the bushfires. and February 2007. With climate change predictions Melbourne, Geelong, the Latrobe Valley and East indicating an increase in the risk and severity of Gippsland were the worst affected areas. bushfires, large-scale smoke impacts similar to those of the summer of 2006—07 may become more All regions had high levels of particle pollution. For commonplace in Victoria. example, in a typical summer Melbourne would expect to have only one or two days with high levels of fine During the 2006—07 bushfires, EPA installed particles, but during the bushfires 15 days were additional monitoring stations in populated areas affected. Melbourne, Geelong and the Latrobe Valley closer to the fires (at Wangaratta and Bairnsdale, also experienced high levels of ozone. augmenting the existing Victorian network of 15 stations) to assess the massive impact these fires had EPA, with assistance from the Bureau of Meteorology on Victorian air quality. This equipment analysed the and the Department of Sustainability and level of bushfire smoke and compared these Environment, forecast the smoke impacts from the measurements to Victorian and Australian air quality fires. -

Legislative Assembly

12902 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Wednesday 4 March 2009 ______ The Speaker (The Hon. George Richard Torbay) took the chair at 10.00 a.m. The Speaker read the Prayer and acknowledgement of country. BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE Notices of Motions General Business Notices of Motions (General Notices) given. VICTORIAN BUSHFIRES Condolence Motion Debate resumed from 3 March 2009. Ms PRU GOWARD (Goulburn) [10.07 a.m.]: I join my parliamentary colleagues in offering my condolences and those of the people of Goulburn to the people of Victoria. When the fires were burning their relentless and tragic course across that State, we all watched, in hypnotised horror, news reports of their disastrous journey. We tuned in to weather bulletins, hoping and praying for a cool and wet change to pull the fires up short, to no avail. We all know the end of that dreadful day in February 2009. As the full extent of the devastation unfolded over the following few days, no-one was left untouched by the destruction. We learnt a lot of things about our fellow Australians as stories were told of impossible choices, forces unimaginable, moral dilemmas and simple gestures of deep humanity, like the group of adults found huddled dead over a baby, sheltering it from the heat—such a simple, futile, loving gesture in the midst of all that fear and dying. As we listened and learnt, all of us, deep inside, must surely have asked, "What would I have done?" The confrontation between our fragile mortality and the forces of nature on that day will continue to shock and touch us for months and years to come. -

Report: the Incidence and Severity of Bushfires Across Australia

Chapter 2 – Previous bushfire inquiries 2.1 The substantial number of previous inquiries into bushfires in Australia was noted on many occasions in evidence to this committee inquiry. This chapter briefly considers the findings of major recent bushfire inquiries and explores the frustrations many in the community feel about apparent political inaction in response. 2.2 Since 1939, there have been at least 18 major bushfire inquiries in Australia, including state and federal parliamentary committee inquiries, COAG reports, coronial inquiries and Royal Commissions. They are listed as follows: • 1939 (Victoria): Report of the Royal Commission to inquire into the causes of and measures taken to prevent the bush fires of January, 1939. L.E.B. Stretton. • 1961 (Western Australia): Report of the Royal Commission appointed to enquire into and report upon the bush fires of December 1960 and January, February and March 1961, Western Australia. G.J. Rodger. • 1967 (Tasmania): The bush fire disaster of 7th February, 1967: report and summary of evidence. D.M. Chambers and C.G. Brettingham-Moore. • 1977 (Victoria): Report of the Board of Inquiry into the occurrence of bush and grass fires in Victoria. E. Barber. • 1984 (Victoria): Report of the Bushfire Review Committee on bushfire preparedness in Victoria, Australia, following the Ash Wednesday fires 16 February 1983. S.I. Miller et. al. • 1984 (national): 'Bushfires and the Australian environment', Report by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Environment and Conservation. P. Milton, Chair. • 1994 (NSW): Report of the Select Committee on Bushfires, Parliament of New South Wales, Legislative Assembly. • 1996 (NSW): Recommendations from the New South Wales Inquiry into 1993/94 Fires, NSW State Coroner’s Office. -

Grampians Bushfire Management Strategy 2020 Fuel Management Bushfire Risk Engagement Areas

Grampians Bushfire Management Strategy 2020 Fuel management Bushfire Risk Engagement Areas Acknowledgements We acknowledge and respect Victoria’s Traditional Owners as the original custodians of the state’s land and waters, their unique ability to care for Country and deep spiritual connection to it. We honour Elders past and present, whose knowledge and wisdom has ensured the continuation of culture and traditional practices. We are committed to genuinely partner and meaningfully engage with Victoria’s Traditional Owners and Aboriginal communities to support the protection of Country, the maintenance of spiritual and cultural practices and their broader aspirations in the 21st century and beyond. We would like to acknowledge the numerous people within DELWP, Parks Victoria, the CFA and local governments who contributed to the discussions and decision-making processes that resulted in this strategy. We would also like to acknowledge stakeholder groups and community members for their interest and input into this planning process. Aboriginal people should be aware that this publication may contain images or names of deceased persons in photographs or printed material. Photo credit Glenn Rudolph, DELWP © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2020 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) logo. -

The Word 'Bushfire' Hits a Nerve in Every Australian. Bushfires Can

NATURAL DISASTERS 1BUSHFIRE The word ‘bushfire’ hits a nerve in every Australian. Bushfires can strike with terrible ferocity and astonishing speed. And Australia has suffered some of the worst. FIRE DANGER RATING Two or three deck headline here please A case study … Through the flames, the dreadful cost in Fact file n The chance of an urban house energy used to power Victoria for a please The warnings were many that Saturday, February 7, 2009 could bring lives and dollars located near a forest being burned year. in any year is, on average, about 1 n Fires need three things – oxygen, disaster to Victoria. in 6500. heat and fuel. If one element is n Half of Victoria’s native forests and removed, fire cannot exist. UCH of Australia is fire prone. Whether or not a blaze HE day was windy and hot, HE costs of disastrous woodlands have burned since late n Oxygen content must be about DEATH TOLLS AROUnd THE WORLD escalates into a natural disaster depends on how intense with record temperatures bushfires are counted in 2002. 16 per cent to support a fire: the air Mthe fire is and who and what are caught in its path. But did Tin many areas, including in Tmany ways, including by Top 10 most important wildfire disasters 1900 to 2011; numbers killed at n Fires burn faster uphill, with the around us is usually about 21 per you know that uncontrolled burning in forests, scrub, grasses and Melbourne which reached 46.4 human deaths and injuries, the country level speed of a front doubling for every cent oxygen. -

1 Victoria's Bushfire Safety Policy

VICTORIA’S BUSHFIRE SAFETY POLICY 1 Volume II: Fire Preparation, Response and Recovery 1 Victoria’s bushfire safety policy During the bushfires of January and February 2009 individuals and fire agencies made crucial decisions that affected many lives. These decisions were made in the context of a broad policy relating to bushfire safety, known colloquially as ‘stay or go’ but more accurately described as ‘prepare, stay and defend or leave early’. The Commission investigated how the stay or go policy performed under the extreme conditions of Black Saturday. Although its investigation brought to light shortcomings in the policy as it applied on that day, it also revealed elements of the policy that continue to be relevant. Each bushfire is unique in its point of ignition, speed and impact, and there is great variation in how individuals and communities plan for and respond to bushfires. The Commission considers that a more comprehensive policy is required—one that better accommodates the diversity of bushfires and human responses. This chapter looks at the changes necessary for fire agencies, communities and individuals. The human and environmental impact of fire is influenced by the way fire agencies and individuals respond and how a particular fire burns. On 7 February 2009 factors such as fuel loads, weaknesses in the responses of fire agencies and individuals, extreme weather conditions, and an environment predisposed (as a result of drought) to a catastrophic event combined to produce one of Australia’s worst natural disasters. Fierce fires such as those experienced on Black Saturday inevitably tested the stay or go policy, exposing its deficiencies—particularly in relation to severe weather, which is when the most serious fires can occur.