S Movements Against the Farm Laws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Misplaced Outrage Over Decision to Halt GM Crop Trials

Misplaced outrage over decision to halt GM crop trials 31 August 2014 | Views | By Narayanan Suresh Misplaced outrage over decision to halt GM crop trials The reported assurance of Environment Minister, Mr Prakash Javadekar, to anti-GM activitists who called on him to keep in abeyance the regulatory approval for the field trials of 15 crops, has predictably created a storm across the country. The mainstream media has accused the Narendra Modi government of pandering to the whims of organizations like the Swadesi Jagaran Manch (SJM) and Bharatiya Kisan Sangh (BKS) in preventing cultivation of new genetically modified (GM) crops in the country. Both these organizations are loose affiliates of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) which is the dominant constituent of the ruling NDA coalition. But most of these die-hard opponents of the government decision, to put on hold the regulatory approval taken by the Genetic Engineering Approval Committee (GEAC) on July 18, 2014, are missing the point. The Modi government would have actually betrayed the trust of the people if it allowed introduction of new GM crops. For the BJP manifesto in 2014 had clearly stated that "GM foods will not be allowed without full scientific evaluation of their long-term impact on soil production and biological impact on consumers." Obviously, the manifesto had taken inputs from various affiliated organizations and so the party could not have gone against its stated policy after assuming power. Of the 15 approvals for confined trials granted by GEAC, four are food crops -- mustard, brinjal, rice and chickpea. And the GEAC has also allowed the import of GM soybean oil by three MNCs -- Monsanto, Bayer BioScience and BASF. -

Protesting Farmers Are a Picture of Hope

2 Months On, 60 Lives Lost, 9 Rounds of Talks: Protesting Farm... https://www.newsclick.in/2-months-60-lives-lose-9-rounds-talks... (/) (https://hindi.newsclick.in/) Politics (/politics) Economy (/economy) !ह#$ी For latest updates on nCOVID-19 around the world visit our INTERACTIVE COVID MAP × (https://covid.newsclick.in/) Covid-19 (/articlelist/covid-19) Science (/science) Culture (/culture) India (/india) AgricultureInternational (/articlelist/Agriculture (/international) Sports) Protests (/sports & Movements) Articles ((/articlelist/Protests/articlelist/our-articles & Movements) ) Politics (/articlelist/Politics) India (/articlelist/India) Videos (/articlelist/our-videos) 2 Months On, 60 Lives Lost, 9 Rounds of Talks: Protesting Farmers are a Picture of Hope (/2-months-60-lives-lose-9-rounds-talks-protesting-farmers-picture-hope) “Patience and courage to bear losses are key to farming. So, the government better not test our patience,” said a farmer. Tarique Anwar (/author/Tarique Anwar) 15 Jan 2021 New Delhi: Despite several weeks of acrimonious interaction with the Central government, farmers agitating against the three contentious agricultural laws have not lost hope. The optimist peasants, camping at "ve entry points of Delhi, say that the ruling dispensation will come to its senses and repeal the legislations sooner or later. (ht (tpht 1 di 11 19/01/2021, 09:49 2 Months On, 60 Lives Lost, 9 Rounds of Talks: Protesting Farm... https://www.newsclick.in/2-months-60-lives-lose-9-rounds-talks... Two days after celebrating(/) Lohri at the protest sites away from their families, they are set to celebrate Baisakhi as well if the government does not accedes to their of roll back the farm laws enacted in September last year and legal guarantee on the minimum support price (MSP)!ह#$ी (—https://hindi.newsclick.in/ the agricultural produce) Politics price ( /politicsdeclared) byEconomy the Government (/economy of) India for direct procurement from farmers. -

The Saffron Wave Meets the Silent Revolution: Why the Poor Vote for Hindu Nationalism in India

THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tariq Thachil August 2009 © 2009 Tariq Thachil THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA Tariq Thachil, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 How do religious parties with historically elite support bases win the mass support required to succeed in democratic politics? This dissertation examines why the world’s largest such party, the upper-caste, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has experienced variable success in wooing poor Hindu populations across India. Briefly, my research demonstrates that neither conventional clientelist techniques used by elite parties, nor strategies of ideological polarization favored by religious parties, explain the BJP’s pattern of success with poor Hindus. Instead the party has relied on the efforts of its ‘social service’ organizational affiliates in the broader Hindu nationalist movement. The dissertation articulates and tests several hypotheses about the efficacy of this organizational approach in forging party-voter linkages at the national, state, district, and individual level, employing a multi-level research design including a range of statistical and qualitative techniques of analysis. In doing so, the dissertation utilizes national and author-conducted local survey data, extensive interviews, and close observation of Hindu nationalist recruitment techniques collected over thirteen months of fieldwork. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Tariq Thachil was born in New Delhi, India. He received his bachelor’s degree in Economics from Stanford University in 2003. -

Farmer Suicides and the Political Economy of Agrarian Distress in India

Working Paper Series ISSN 1470-2320 2009 No.09-95 Crisis in the Countryside: Farmer Suicides and The Political Economy of Agrarian Distress in India Balamuralidhar Posani Published: February 2009 Development Studies Institute London School of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street Tel: +44 (020) 7955 7425/6252 London Fax: +44 (020) 7955-6844 WC2A 2AE UK Email: [email protected] Web site: www.lse.ac.uk/depts/destin Page 2 of 52 Abstract The recent spate of suicides among farmers in India today is a manifestation of an underlying crisis in agriculture which is a result of the marginalization of agrarian economy in national policy since the economic reforms of the 90s. Given the apparently insurmountable political power of the rural lobby at the end of the 80s, this would seem as a paradox. A nuanced analysis reveals, however, that there are economic constraints to how far rural power can go, in addition to self-limitations to its collective action due to conflicting identities like class, caste, region and religion. In part the marginalization of agriculture since the 90s might be explained by the shrinking policy space for national governments under increasingly supranational regimes of a changing global political economy. But to the extent that the change in economic priorities was a choice that the Indian government made, the political feasibility for this was provided by the growing ethnicization and communalization of political discourse in India since the 90s which subsumed the political force of the agrarian interest. The relative quiescence in Farmers’ Movements today is also to be seen in the context of the slow but remarkable flux within the contemporary rural society which is changing the identities of the farmers and how they relate to farming and the village. -

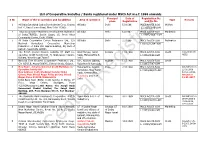

List of Cooperative Societies / Banks Registered Under MSCS Act W.E.F. 1986 Onwards Principal Date of Registration No

List of Cooperative Societies / Banks registered under MSCS Act w.e.f. 1986 onwards Principal Date of Registration No. S No Name of the Cooperative and its address Area of operation Type Remarks place Registration and file No. 1 All India Scheduled Castes Development Coop. Society All India Delhi 5.9.1986 MSCS Act/CR-1/86 Welfare Ltd.11, Race Course Road, New Delhi 110003 L.11015/3/86-L&M 2 Tribal Cooperative Marketing Development federation All India Delhi 6.8.1987 MSCS Act/CR-2/87 Marketing of India(TRIFED), Savitri Sadan, 15, Preet Vihar L.11015/10/87-L&M Community Center, Delhi 110092 3 All India Cooperative Cotton Federation Ltd., C/o All India Delhi 3.3.1988 MSCS Act/CR-3/88 Federation National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing L11015/11/84-L&M Federation of India Ltd. Sapna Building, 54, East of Kailash, New Delhi 110065 4 The British Council Division Calcutta L/E Staff Co- West Bengal, Tamil Kolkata 11.4.1988 MSCS Act/CR-4/88 Credit Converted into operative Credit Society Ltd , 5, Shakespeare Sarani, Nadu, Maharashtra & L.11016/8/88-L&M MSCS Kolkata, West Bengal 700017 Delhi 5 National Tree Growers Cooperative Federation Ltd., A.P., Gujarat, Odisha, Gujarat 13.5.1988 MSCS Act/CR-5/88 Credit C/o N.D.D.B, Anand-388001, District Kheda, Gujarat. Rajasthan & Karnataka L 11015/7/87-L&M 6 New Name : Ideal Commercial Credit Multistate Co- Maharashtra, Gujarat, Pune 22.6.1988 MSCS Act/CR-6/88 Amendment on Operative Society Ltd Karnataka, Goa, Tamil L 11016/49/87-L&M 23-02-2008 New Address: 1143, Khodayar Society, Model Nadu, Seemandhra, & 18-11-2014, Colony, Near Shivaji Nagar Police ground, Shivaji Telangana and New Amend on Nagar, Pune, 411016, Maharashtra 12-01-2017 Delhi. -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Jats Into Kisans

TIF - Jats into Kisans SATENDRA KUMAR April 2, 2021 Farmers attending the kisan mahapanchayat at Muzaffarnagar, Uttar Pradesh, 29 January. The tractors carry the flag of the Bharatiya Kisan Union | ChalChitra Abhiyaan The decline of farmer identity from the 1990s brought a generation of upwardly mobile Jats close to the BJP. The waning of urban economic opportunities has reminded youth of the security from ties to the land, spurring the resistance to the farm laws. Following the Bharatiya Janata Party government’s attempt earlier this year to forcibly remove farmers protesting the farm laws on the borders of Delhi, the epicentre of the movement has shifted deep into the Jat- dominated villages of western Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Haryana. The large presence of Muslim farmers in the several kisan mahapanchayats across the region has been read as a sign of a reemergence of a farmers’ identity, an identity that had been torn apart by the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots that pitted the mostly Hindu Jats against Muslims. Neither the Jat claim to Hindutva a few years ago nor the re-emergence of a farmer identity in the present happened overnight. The deepening agrarian crisis and changes in social relations in western UP since the 1990s had accelerated social and spatial mobilities in the region, leading to fissures in the farmer’s polity and the BJP gaining politically. A younger generation of upward mobile Jats, dislocated from agriculture, hardly identified with the kisan identity. Urban workspaces and cultures began shaping their socio-political identities. New forms Page 1 www.TheIndiaForum.in April 2, 2021 of sociality hitched their aspirations to the politics of the urban upper-middle classes and brought them closer to the politics of the Hindu right. -

Unit 8 Farmers' Movement

UNIT 8 FARMERS’ MOVEMENT Structure 8.1 Introduction Aims and Objectives 8.2 Farmers’ Movement after Independence 8.3 New Farmers’ Movement 8.3.1 The Beginning 8.3.2 Major Struggles of New Farmers’ Movement 8.3.3 Debate about Newness of New Farmers’ Movement 8.3.4 Movements beyond Local to Global 8.3.5 Ideology of Farmers’ Movement 8.3.6 Party Politics and Division among Farmers’ Movement 8.3.7 Social Bases of Farmers’ Movement 8.4 Summary 8.5 Terminal Questions Suggested Readings 8.1 INTRODUCTION India has a long history of peasant or farmers’ movement, dating back to the colonial period when farmers in different parts of India revolted against Zamindars, landlords, British colonial masters or powers including feudal lords. These movements were the results of severe exploitation, oppression, loss of rights over land, imposition of new taxes, and new agrarian relations of the peasants with the Colonial state or the feudal lords. Most of the struggles that the peasants resorted to were either carried as part of nationalist struggle or independent of it. Some of the important struggles of farmers or peasants during the British period were : Bhil Revolt ( 1822,1823,1837-60), Deccan Peasant Revolt (1875), Mopilla Revolt (1921), The Muslhi Satyagraha (1921-24), Struggle of Warlis (1945), Birsa Munda revolt Nagar Peasant Uprising(1830-33). In this context, three important struggles that Gandhi led require our special attention. They were: Champaran (1918-19); Bardoli (1925) and Kheda(1918). In the first struggle, the primary issue was opposing the Tinkathia System imposed on the Indigo cultivators of Champaran by the colonial powers. -

Suicides and the Making of India's Agrarian Distress

1 SUICIDES AND THE MAKING OF INDIA’S AGRARIAN DISTRESS A.R. Vasavi National Institute of Advanced Studies IISc Campus Bangalore-560012 INDIA [email protected] 2 SUICIDES AND THE MAKING OF INDIA’S AGRARIAN DISTRESS Abstract Drawing on a socio- anthropological approach, this article reviews data from five states of India where suicides by agriculturists have taken place since 1998. Linking macro and micro economic factors to social structural and symbolic meanings, the article highlights the ways in which a range of new risks and contradictory social trends render the lives of agriculturists into distress conditions. Such conditions of distress are compounded by the social structuring of commercial agriculture that has led to the ‘individualization of agriculturists’. These trends combine with the larger context of neo-liberal India, where agricultural issues and agriculturists are in a state of ‘advanced marginalization’, and account for the making of distress in which large numbers of agriculturists have taken their lives. 3 SUICIDES AND THE MAKING OF INDIA’S AGRARIAN DISTRESS A.R. Vasavi Between the years 1998 and 2000, news of suicides among agriculturists trickled through some newspapers and television channels. By 2004, the suicides became the index of a crisis in India’s agriculture and led to widespread debates and reports. Even as the suicides in Maharashtra gained momentum between 2005-6, enforcing the Prime Minister to visit the region and declare ‘monetary relief packages’, the nature of the suicides gained another dimension. In Mysore, four agriculturists attempted to commit suicide in the Deputy Commissioner’s office grounds, and several of those committing suicide in the Vidharbha region of Maharashtra wrote notes addressed to the government1. -

Country Advice

Country Advice India India – IND39421 – Christians – Karnataka – Bangalore – Sangh Parivar 4 November 2011 1. Please provide an update on the situation for Christians in the state of Karnataka since response number IND34452 dated 27 February 2009? Please include information about the situation in Bangalore in particular. Karnataka was the state in India with the highest number of attacks on Christians during 2009 and 2010,1 and has continued to be a high volume of attacks against Christians during 2011.2 The situation of Christians in Karnataka has reportedly deteriorated since the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won government in that state in 2008, with a subsequent rise in violence by Hindu nationalists against Christians.3 The BJP is the political wing of the Sangh Parivar, a collective of Hindu nationalist groups in India (information on the Sangh Parivar can be found in the response to Question 2). There is also information available indicating that the government does not acknowledge the level of violence against Christians,4 and that the security forces and lower judicial system are involved in this mistreatment.5 Reports were located referring to mistreatment of Christians in Karnataka during 2011 by Hindus and members of the security forces.6 Reports were also located which refer to mistreatment of Christians in Bangalore, the capital of Karnataka, during 2010 and 2011 by Hindus, Muslims and members of the security forces.7 Treatment of Christians in Karnataka 1 Howell, R. 2010, „Religion, Politics and Violence: A Report of the Hostility and Intimidation faced by Christians in India in 2010‟, International Institute for Religious Freedom website, source: Evangelical Fellowship of India, 22 December, pp. -

Transnational Entanglements of Hindutva and Radical Right Ideology

Reconfiguring nationalism: Transnational entanglements of Hindutva and radical right ideology Eviane Leidig Dissertation submitted for the degree of Ph.D. Department of Sociology and Human Geography Faculty of Social Sciences University of Oslo 2019 © (YLDQH/HLGLJ, 2020 Series of dissertations submitted to the Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Oslo No. ISSN 1564-3991 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. Cover: Hanne Baadsgaard Utigard. Print production: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo. ii Dedicated to Professor Vernon F. Leidig, who taught me how to listen. iii Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................... vi Glossary ........................................................................................................................................... vii Summary ........................................................................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. xii 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 2 Background ................................................................................................................................ -

Open Letter on Lack of Consultation with People in Rcep Negotiations

OPEN LETTER ON LACK OF CONSULTATION WITH PEOPLE IN RCEP NEGOTIATIONS To The Honourable Minister, Minister of Commerce & Industry (MOCI) Government of India New Delhi 14th September 2019 REF: Ministry list uploaded on 24 August, 2019, regarding stakeholder consultations Dear Shri Piyush Goyal, This is with reference to media reports, which mention that the Department of Commerce (DOC) of the Government of India held over 100 consultations across the country over the last six years to gather reactions to the proposed mega regional Free Trade Agreement – the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). This is misleading on two accounts, on the one hand, internal briefings and inter-ministerial consultations form a significant part of these so called stakeholder consultations, and on the other hand, the only stakeholder that has been consulted is the industry. The interactions give primacy to various industry representatives. There have been no consultations with trade unions, farmers’ organisations, public interest groups, or any people’s community that stands to be impacted by RCEP. We, a network of concerned citizens, academics, researchers, farmer organisations, livestock keepers, fisher folk, labour unions, patient groups, women’s collectives and other marginalised groups have been raising our concerns with respect to RCEP to the Ministry as well as to some of our trade negotiators. We had also met with your predecessor, Honourable Minister Nirmala Sitharaman. But there has not been any consultative process held by DOC, MOCI with civil society. Our earlier representations to you or to the line ministries with which we are directly concerned, to hold wider consultative processes, beyond big industry, have borne no fruit.