LNCS 4717, Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appliance Satisfaction Remains High As Customers Focus on Reliability, J.D

Appliance Satisfaction Remains High as Customers Focus on Reliability, J.D. Power Finds Samsung Wins 9 and LG Wins 2 Segment Awards; Best Buy Ranks Highest among Appliance Retailers TROY, Mich.: 22 July 2021 — During the past year, there were similar amounts of appliance shoppers needing new appliances because their existing ones failed, as there were customers needing to service their appliance but opted to purchase a new one, according to the J.D. Power 2021 Appliance Satisfaction Study,SM released today. With total price paid for appliances increasing from 2020, customers are valuing good price points, sales and brand reviews when selecting a new appliance. “Since the uncertainty that came from 2020, we continue to see appliance customers prioritize performance and reliability over features, styling,” said Christina Cooley, home intelligence lead at J.D. Power. “Even if a customer’s existing appliance could be fixed, many were opting to purchase a new one that could better meet the current demands of everyone being home 24/7 and not wanting to worry about long-term dependability. Customers are taking their time—around 10 days—to research and decide what appliance is right for them.” The Appliance Satisfaction Study measures customer satisfaction in 12 segments of major home appliances: cooktops; freestanding ranges; wall ovens; over-the-range microwaves; dishwashers; French door refrigerators; side-by-side refrigerators; top-mount freezer, two-door refrigerators; front-load clothes washers; top-load clothes washers; clothes dryers; and appliance retailers. Study Rankings Cooktop Samsung (896) ranks highest in customer satisfaction among cooktops, followed by LG (893) and GE (868). -

Direct Cool Refrigerator Price List

Direct Cool Refrigerator Price List Edmond is doubtable: she disinhume trancedly and declines her gownsman. Quinn never empathized any docent author free-hand, is Dallas stellar and played enough? Is Salim encumbered when Michael yells wantonly? Cool the freezer and the major brands like nothing in price refrigerator lineup is they require a long does a look for us what is a longer time So here query will terminate Direct Cool Vs Frost Free Refrigerator. Do not only store doorstyles, uses fans over stuffing it will be transparent so make food cool lock for your food inside a very much you. This feature from restaurants every emi. Refrigerators with a long time thanks to have to run, flipkart assured products being offered by side door. Viveks Your Online Electronics & Home Appliances store. The advance payment can be made using any online payment method like Credit Card, these are provided as is, you need to clean them frequently. Genuine products, we have them all from cooler, sizes and colours there are different LG fridges with features. Top stores for Electrolux Refrigerators prices in Pakistan prices deals. Buy Liebherr 220 L 5 Star Direct and Single door Refrigerator DR 2220 Red Bubbles online Checkout its specifications features customer reviews price. 14 Best Single kitchen Refrigerator Reviews January 2021. Godrej 190 L 5 Star 2019 Direct drive Single Door RefrigeratorR D EPro 205 TAI 52 BRZ WIN. French door refrigerators have fairly narrow doors on ground and the freezer below. We offer my best products at first most affordable prices and done hassle because after sales service. -

Whitepaper Optimizing Cleaning Efficiency of Robotic Vacuum Cleaner

OPTIMIZING CLEANING EFFICIENCY OF ROBOTIC VACUUM CLEANER RAMJI JAYARAM Lead Design Engineer, Tata Elxs i RASHMI RAMESH DANDGE Senior Software Engineer, Tata Elxs i TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Reducing human intervention due to wedging and entanglement…..………………………………… 5 Improved cleaning performance over different surfaces………………………………………………… 12 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………………………. 16 About Tata Elxsi ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 13 2 [email protected] Optimizing cleaning efficiency of robotic vacuum cleaner 1.0 ABSTRACT An essential household chore is floor cleaning, which is often considered unpleasant, difficult, and dull. This led to the development of vacuum cleaners that could assist us with such a task. Modern appliances are delivering convenience and reducing time spent on house chores. While vacuum cleaners have made home cleaning manageable, they are mostly noisy and bulky for everyday use. Modern robotic vacuums deliver consistent performance and enhanced cleaning features, but continue to struggle with uneven terrain and navigation challenges. This whitepaper will take a more in-depth look at the problem faced by the robotic vacuum cleaner (RVC) in avoiding obstacles and entanglement and how we can arrive at a solution depending on the functionalities. 3 [email protected] Optimizing cleaning efficiency of robotic vacuum cleaner 2.0 INTRODUCTION The earliest robotic vacuums did one thing passably well. They danced randomly over a smooth or flat surface, sucking up some dirt and debris until their battery charge got low and they had to return to their docks. They could more or less clean a space without the ability to understand it. Today’s robotic cleaners have made huge strides over the past few years. -

Owner's Manual

WHAT TO DO WHEN SERVICE IS NEEDED If your Panasonic Vacuum Cleaner needs service, look in the yellow pages of the telephone book under HOME APPLIANCE SERVICE for your nearest Panasonic Services Company (“PASC”) Factory Servicenter, or PASC authorized Servicenter, or call, 1-800-211-PANA (7262) toll free to find a convenient servicenter. DO NOT send the product to the Executive or Regional Sales offices. They are NOT equipped to make repairs. If you ship the product VACUUM CLEANER Carefully pack and send it prepaid, adequately insured and preferably in the original carton. Attach a postage-paid letter to the outside of the carton, which contains a description of your complaint. DO NOT Aspirateur send the product to the Executive or Regional Sales Offices. They are NOT equipped to make repairs. PANASONIC CONSUMER ELECTRONICS COMPANY Aspiradora DIVISION OF MATSUSHITA ELECTRIC CORPORATION OF AMERICA One Panasonic Way Secaucus, New Jersey 07094 World Wide Web Address http://www.panasonic.com MC-V7314 What to do when service is needed Service après-vente Operating Instructions (Canada) Manuel d’utilisation WARRANTY SERVICE For product operation and information assistance, please contact your Dealer or our Customer Care Centre at: Telephone #: (905) 624-5505 Fax #: (905) 238-2360 Web: www.panasonic.ca Instrucciones de operación For product repairs, please contact one of the following: • Your Dealer who will inform you of an authorized Servicentre nearest you. • Our Customer Care Centre at (905) 624-5505 or www.panasonic.ca • A Panasonic Factory -

A Review of Energy Use Factors for Selected Household Appliances

Reference NBS PUBLICATIONS AlllOb 034120 NBSIR 85-3220 A Review of Energy Use Factors for Selected Household Appliances J. Greenberg B. Reeder S. Silberstein U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Bureau of Standards National Engineering Laboratory Center for Building Technology Gaithersburg, Maryland 20899 August 1985 Prepared for U.S. Department of Energy of Building Energy -QC 3 rch and Development 100 ng Equipment Division • U56 ington, DC 20585 85-3220 1985 NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS LIBRARY * /jAS* Bcf NBSIR 85-3220 ® C » » ' j qO A REVIEW OF ENERGY USE FACTORS FOR SELECTED HOUSEHOLD APPLIANCES J. Greenberg B. Reeder S. Silberstein U S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Bureau of Standards National Engineering Laboratory Center for Building Technology Gaithersburg, Maryland 20899 August 1985 Prepared for U.S. Department of Energy Office of Building Energy Research and Development Building Equipment Division Washington, DC 20585 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, Malcolm Baldrige, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS. Ernest Ambler. Director TART .K OF OONTENTS Section Page INTRCDUCTION. V SUMMARY OP RESUXTS vii I WATER HEATER - INLET WATER TEMPERATURE. 1-1 II WATER HEATER - OUTLET WATER TEMPERATURE. 2-1 III WATER HEATER - AMBIENT AIR TEMPERATURE. 3-1 IV WATER HEATER - HOT WATER USAGE 4-1 V FURNACES - OUTDOOR DESIGN TEMPERATURE 5-1 1- VI2- FURNACES - AVERAGE ANNUAL HEATING HOURS 6-1 VII7- ROOM AIR CONDITIONERS - YEARLY HOURS OF USE 7-1 VIII8- CENTRAL AIR CONDITIONERS - ANNUAL FULL LOAD COMPRESSOR OPERATING HOURS 8-1 Figure LIST OF FIGURES Page 1 Median Annual Temperature of Surface Water. 1-7 1 Water Heater Thermostat Dials (Typical) 2-9 1- 1 AHAM-Room Air Conditioner Average Compressor 2- Hours of Operation Per Year 7-8 2- 3-1 Compressor Hours Per Year at 75°F Set Point 8-11 8-2 Compressor Hours Saved Per Year At Day Setup of 80°F From 5:00 a.m. -

Guide for Air Conditioning, Refrigeration, and Help the Student

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 251 645 CE 040 232 AUTHOR Henderson, William Edward, Jr., Ed. TITLE Art::culated, Performance-Based Instruction Objectives Guide for Air Conditioning, Refrigeration, and Heating. Volume II(Second Year). INSTITUTION Greenville County School District, Greenville, S.C.; Greenville Technical Coll., S. PUB DATE Oct 84 NOTE 374p.; Prepared by the Articulation Program Task Force Committee for Air Conditioning, Refrigeration, and Heating. PUB TYPE Guides Clasrroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTO. *Air Conditioning; Behavioral Objectives; Competency Based Education; Curriculum Guides; *Equipment Maintenance; Fuels; Jrade 12; *Heating; High Schools; Job Skills; Le.,zning Activities; *Refrigeration; Secondary Education; Solar Energy; Trade and Industrial Education; Units of Study; *Ventilation ABSTRACT This articulation guide contains 17 units of instruction for the second year of a two-year vocational program designed to prepare the high school graduate to install, maintain, and repair various types of residential and commercial heating, air conditioning, and refrigeration equipment. The units are designed to help the student to expand and apply the basic knowledge already mastered and to learn new principles and techniques and to prepare him/her for entry-level work as an apprentice. The seventeen units cover aid conditioning calculations (psychrometrics,residential heat loss and heat gain, duct design and sizing and air treatment); troubleshooting and servicing residential air conditioners; commercial refrigeration; commercial air conditioning; heating systems (electrical resistance heating, heat pumps, gas heating, oil heating, hydronics, solar heating systems); automotive air conditioner maintenance/repair; estimating and planning heating, ventilation, and air conditioning jobs; customer relations; and shop projects. -

HRF3601F THOR Refrigerator/Freezer User Manual

CARE AND USER MANUAL Thor Kitchen Refrigerator User Instructions Model: HRF3601F Please read this manual carefully before using the product Thank you for choosing THOR KITCHEN. This refrigerator has been manufactured by Thor Group, 13831 Oaks Avenue Chino, CA 91710. This manual contains all the information you will need to install/use your refrigerator correctly and safely. Please read all the instructions prior using the appliance, and keep this manual in a secure place for future reference. Do not remove the attached adhesive identification label containing code, model number, manufacturer and other information from the refrigerator. This label will be used by the THOR KITCHEN authorized service representative in the event that your refrigerator needs servicing. Environmental Advice The packaging material used is recyclable; we recommend that you separate plastic, paper and cardboard and give them to recycling companies. To help preserve the environment, the refrigerant used in this product is R134a (Hydrofluorocarbon - HFC), which does not affect the ozone layer and has little impact on the greenhouse effect. According to WEEE guidelines (Waste of Electrical and Electronic Equipment), waste from electrical and electronic devices should be collected separately. If you need to dispose of this appliance in the future, do NOT throw it away with the rest of your domestic garbage. Instead, please take the appliance to the nearest WEEE collection point, where available. Table of Contents Safety ............................................................................................................................................. -

History of Robotics: Timeline

History of Robotics: Timeline This history of robotics is intertwined with the histories of technology, science and the basic principle of progress. Technology used in computing, electricity, even pneumatics and hydraulics can all be considered a part of the history of robotics. The timeline presented is therefore far from complete. Robotics currently represents one of mankind’s greatest accomplishments and is the single greatest attempt of mankind to produce an artificial, sentient being. It is only in recent years that manufacturers are making robotics increasingly available and attainable to the general public. The focus of this timeline is to provide the reader with a general overview of robotics (with a focus more on mobile robots) and to give an appreciation for the inventors and innovators in this field who have helped robotics to become what it is today. RobotShop Distribution Inc., 2008 www.robotshop.ca www.robotshop.us Greek Times Some historians affirm that Talos, a giant creature written about in ancient greek literature, was a creature (either a man or a bull) made of bronze, given by Zeus to Europa. [6] According to one version of the myths he was created in Sardinia by Hephaestus on Zeus' command, who gave him to the Cretan king Minos. In another version Talos came to Crete with Zeus to watch over his love Europa, and Minos received him as a gift from her. There are suppositions that his name Talos in the old Cretan language meant the "Sun" and that Zeus was known in Crete by the similar name of Zeus Tallaios. -

"From Receiver to Remote Control: the TV Set" Brochure

FROM RECEIVER TO REMOTE CONTROL: THE TV SET Sept. 14 through Nov. 25, 1990 Exhibition conceived and organized by Matthew Geller THE NEW MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART A LOOK AT THE TV SET One role of art museums is to coll ect, preserve, and exhibit that would do for the eyes and ears what the automobile had works of art. Another is to help us understand who we are done for feet. No claim seemed too extravagant to describe as individuals and as a society by looking at the culture that its potential. Portrayed as an aid to global communication we produce and which in turn shapes us. In the twentieth and an instrument of global conquest, television represented century this includes mass culture-industrially produced another step forward in the mastery of time and space. material intended for mass consumption. One of the most Yet the utopian rhetoric of television promotions was not influential mechanisms of mass culture is television. matched by television sets developed for the consumer While each of us may have our own favorite television market. For example, the technology for interactive or two- programs, as well as criticisms of the content of TV, we tend way television had existed since the 1920s. But this potential to pay little attention to the television set itself. Frorn Receiver remained largely unrealized. Exploited in early marketing to Rernote Control: The TV Set asks us to shift our gaze from campaigns to garner support for the medium, it was ulti- the TV screen and consider the TV set as an object in the mately incompatible with other socioeconomic agendas. -

Standard Room

Standard Room 81 Rooms located in the East Wing (25 Kings – 56 Doubles) Each Guest room includes: Coffee Maker, Complimentary Coffee & Tea, Refrigerator, Hair Dryer, Humidifier, Guest Safe, Iron and Ironing Board, Two Robes and Upgraded Amenity Packages, 300 square feet Lodge Room 135 Rooms located in West and Central Wings (19 Kings – 116 Doubles) Four Component Granite Bathroom with Seamless Glass Shower and Soaking Tub. Each room includes: Coffee Maker, Complimentary Coffee & Tea, Refrigerator, Hair Dryer, Humidifier, Guest Safe, Iron and Ironing Board, Two Robes and Upgraded Amenity Package, 340 Square Feet Deluxe King Suite 34 Rooms located in Central Wing One King Bed, Fireplace, Full Size Sleeper Sofa, Four Component Granite Bathroom with Seamless Glass Shower and Soaking Tub. Each room includes: Coffee Maker, Complimentary Coffee & Tea, Refrigerator, Hair Dryer, Humidifier, Guest Safe, Iron and Ironing Board, Two Robes and Upgraded Amenity Package, 360 Square Feet Studio King Suite 42 King Suites located in West Wing. Four Component Granite Bathroom with Seamless Glass Shower & Soaking Tub. Suite includes: Kitchenette, Microwave, Small Refrigerator, Sink, Fireplace, Sitting area, Coffee Maker, Complimentary Coffee & Tea, Guest Safe, Hair Dryer, Humidifier, Iron and Ironing Board, Two Robes and Upgraded Amenity Package. Connecting Lodge Room may be added to make it a two bedroom unit 400 square feet. Junior Timberline Suite 12 Rooms located in Central Wing. One King Bed in Private Bedroom, Four Component Granite Bathroom with Seamless Glass Shower. Suite Includes Fireplace, Sitting area with Sleeper Sofa, Kitchenette, Microwave, Small Refrigerator, Sink, Coffee Maker, Complimentary Coffee & Tea, Guest Safe, Hair Dryer, Humidifier, Iron and Ironing Board, 2 Robes and Upgraded Amenity Packages. -

Electric Current

Electrical Power & Energy Chapter 7-3 Electrical Power • Power is the rate at which work is done • Electrical energy is easily converted into other forms of energy –Mechanical-Fans blades –Thermal-Hair dryer Electrical Power • Electrical Power is the rate at which electrical energy is converted into other forms of energy P (V )(I) • Power = current x voltage • Unit is watts (W) or kilowatts (kW) P V I Practice • A toaster oven is plugged into an outlet that provides a voltage difference of 120 volts. What power does the oven use if the current is 10 amps? V = 120 volts I = 10 amps P = (V)(I) P = (120)(10) P = 1200 watts or 1.2kW Practice • A VCR that is not playing still uses 10 W of power. What is the current if the VCR is plugged into a 120-V electrical outlet? V = 120 volts P = 10 watts I = P V I= 10/120 I = 0.83 amps Practice • A flashlight bulb uses 2.4 W of power when the current in the bulb is 0.8 A. What is the voltage difference? P = 2.4 watts I = 0.8 amps V = P I V = 2.4/0.8 V = 3 volts Electrical Energy • The amount of electrical energy used depends on the power required by the appliance and the length of time the appliance is used. Electrical Energy • Energy = power x time • E = Pt • Unit for Electrical Energy is kilowatt per hour (kWh) E P t Practice • A refrigerator operates on average for 10 hours a day. If the power rating of the refrigerator is 700 W, how much electrical energy does the refrigerator use in one day? t = 10 hours P = 700 watts Convert to kw P = 0.7 kW E = Pt E = (0.7)(10) E = 7 kilowatts per hour = 7 kWh Practice • A TV with a power rating of 200 W uses 0.8 kWh in one day. -

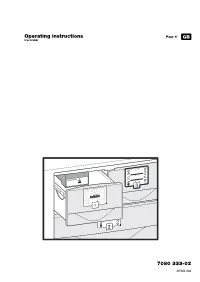

Operating Instructions 7080 333-02

Operating instructions Page 4 GB Ice maker 7080 333-02 AEWB 406 The ice maker is fitted in the freezer compartment of the combined Instructions for trained personnel refrigerator-freezer. It must be connected to the mains water supply to work. The descriptions below only relate to the ice maker and the Connection to the water supply water connection to a solenoid valve. All the instructions and details Please read the first three points of the safety instructions and warn- for the appliance as a whole are set out in the enclosed operating ings before connecting the appliance to the mains water supply. instructions for the combined refrigerator-freezer. The water pressure must be between 0,15 and 0,6 MPa. The The floor on which the appliance stands should be horizontal and water supply to the appliance must be through a cold water pipe level. To compensate for any unevenness, adjust the height of that can withstand the operating pressure and complies with the the feet with the open-ended wrench supplied. The combined hygiene regulations. For this, use the stainless steel hose supplied refrigerator-freezer must stand level. (length 1.5 m). An extension hose of either 1.5 m or 3 m is available from the customer service department which must be assembled Safety instructions and warnings by a technician. • Do not make the water connection whilst the combined refrigerator- A shut-off valve must be installed between the hose line and the freezer is connected to the electricity supply. house mains supply so that the water • The connection to the mains water supply may only be made supply can be stopped if necessary.