Flood Control in Small Urban Rivers: an Example of River Projects in Tokyo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Bus] Meguro-Dori T Okyu Meguro Line JR Y Amanote Line Y Amate-Dori Meguro Station Access](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7153/bus-meguro-dori-t-okyu-meguro-line-jr-y-amanote-line-y-amate-dori-meguro-station-access-287153.webp)

[Bus] Meguro-Dori T Okyu Meguro Line JR Y Amanote Line Y Amate-Dori Meguro Station Access

To Shibuya To Meguroshinbashi Ootorijinjamae Mos Burger Meguro-dori West exit Meguro Maruetsu Police Station Ootori shrine box My Basket drug store RECODS Liquor Seven-eleven West exit shop Gyoninzaka The 4th parking lot (Toll parking, Rakan reservation is needed.) ⑨ Meguro Gajoen Front entrance *Refer to attached map Temple Meguro Arco Tower Station Atre Naboku Line Sunkus Mita Line Rakan Tokyu Meguro Line Kaikan Megurofudo The 3rd parking lot Meguro Line Tokyu Line JR Yamanote The 2nd parking lot (Toll parking, Kinokuniya reservation is needed.) HQ Daikokuya Megurofudosonmae dori Kamurozakashita Super Ozeki Yamate-dori Matsuya Florist's Shinagawa To Fudomae Station Access [Bus] A short walk from “Fudoson Sando” bus stop of Route Shibuya 41 [Train] bound for Ooimachi Station of Tokyu Bus. 10 minute walk from JR/Tokyo Metro Meguro Station (Please take Tokyu Bus from the south exit of Shibuya Station 7 minute walk from Tokyu Line Fudomae Station. or from Tokyu Toyoko Line Nakameguro Station.) [IMAGE STUDIO 109, INC 2-24-12, Shimomeguro, Meguro-ku, Tokyo, 153-0064 (MEGURO CUE building) Studio department Post production department □CCTV department General affairs department TEL.03-5436-9109 FAX.03-3494-8871 Parking lot guide To Nakameguro Ootorijinjamae Meguro-dori Meguroshinbashi Maruetsu Ootori shrine Yamate-dori drug store RECODS Yanagi-dori Meguro River Rakan Temple Sunkus The 3rd parking lot (Reservation is needed.) The 3rd parking lot *Refer to attached map (Reservation is needed.) Multistory car park Megurofudo Daikokuya Kinokuniya HQ The 2nd parking lot To Gotanda [About parking lots] If all the parking lots shown above are full, please use other parking facilities nearby. -

Meguro Walking Map

Meguro Walking Map Meguro Walking Map Primary print number No. 31-30 Published February 2, 2020 December 6, 2019 Published by Meguro City Edited by Health Promotion Section, Health Promotion Department; Sports Promotion Section, Culture and Sports Department, Meguro City 2-19-15 Kamimeguro, Meguro City, Tokyo Phone 03-3715-1111 Cooperation provided by Meguro Walking Association Produced by Chuo Geomatics Co., Ltd. Meguro City Total Area Course Map Contents Walking Course 7 Meguro Walking Courses Meguro Walking Course Higashi-Kitazawa Sta. Total Area Course Map C2 Walking 7 Meguro Walking Courses P2 Course 1: Meguro-dori Ave. Ikenoue Sta. Ke Walk dazzling Meguro-dori Ave. P3 io Inok Map ashira Line Komaba-todaimae Sta. Course 2: Komaba/Aobadai area Shinsen Sta. Walk the ties between Meguro and Fuji P7 0 100 500 1,000m Awas hima-dori St. 3 Course 3: Kakinokizaka/Higashigaoka area Kyuyamate-dori Ave. Walk the 1964 Tokyo Olympics P11 2 Komaba/Aobadai area Walk the ties between Meguro and Fuji Shibuya City Tamagawa-dori Ave. Course 4: Himon-ya/Meguro-honcho area Ikejiri-ohashi Sta. Meguro/Shimomeguro area Walk among the history and greenery of Himon-ya P15 5 Walk among Edo period townscape Daikan-yama Sta. Course 5: Meguro/Shimomeguro area Tokyu Den-en-toshi Line Walk among Edo period townscape P19 Ebisu Sta. kyo Me e To tro Hibiya Lin Course 6: Yakumo/Midorigaoka area Naka-meguro Sta. J R Walk a green road born from a culvert P23 Y Yutenji/Chuo-cho area a m 7 Yamate-dori Ave. a Walk Yutenji and the vestiges of the old horse track n o Course 7: Yutenji/Chuo-cho area t e L Meguro City Office i Walk Yutenji and the vestiges of the old horse track n P27 e / S 2 a i k Minato e y Kakinokizaka/Higashigaoka area o in City Small efforts, L Yutenji Sta. -

Off-Track Betting on Your Doorstep *Charges for Pay-Seats, Etc., Are Valid As of Nov

Ashiyu foot bath at WINS Isawa Excel Floor of WINS Shin-Yokohama Carousel at WINS Shin-Shirakawa WINS Kyoto Entrance to WINS Namba WINS Sasebo in Huis ten Bosch WINS – off-track betting on your doorstep *Charges for pay-seats, etc., are valid as of Nov. 13th, 2009. Did you know that you can place a bet without going to a racecourse? Just pop in to your local WINS off-track betting facility! With branches all over Japan, WINS are also convenient places for meeting spot or just taking a coffee break. Some WINS facilities are set up with comfortable sofas and PC and monitor for your personal use, allowing you to enjoy the whole day at the races! Of course, WINS also make payouts on winning bets. WINS Sapporo(some pay-seats) WINS Shizunai WINS Kushiro WINS Ginza-dori WINS Korakuen (some pay-seats) WINS Kinshicho (some pay-seats) Dodo-Biratori Shizunai Route JR Senmo Main Line Main Senmo JR ▲Sapporo Stn. Homac ▼ 391 Subway Ryogoku Ichikawa ▼ Hokkaido Sales WINS Posful Fujiya Toei Subway Hibiya Line Ginza Stn. Police box Kasuga Stn. Kinshicho Stn. WINS Sapporo Toho Subway Line Shizunai Kushiro Loop Road Setsuribashi Oedo Line JR Sobu Line Cosmo● Shizunai River Kushiro Timber Building B Higashi Ginza Mitsukoshi ● ● ● Subway Fire Station Reservoir ● Korakuen Stn. JR Yurakucho Stn. Hanzomon Line Stn. Dept. Store Expressway ● Suidobashi Stn. Plaza ▲ Miyuki-dori 44 Arche● ●Senshu-An Seiko Mart ● Shizunai Kushiro Rosai● Kushiro Ginza Stn. Tokyo Dome City Shopping Kinshicho Stn. Ginza-dori Kamotsu Showa-dori Attractions T street Police Hospital Yotsume-dori Municipal Nemuro o Marunouchi Line Subway e ● Jidosha Matsuya Dept. -

Approach for International Exchange of River Restoration Technology

Approach for International Exchange of River Restoration Technology Ito, Kazumasa Head of planning office, Research Center for Sustainable Communities, CTI Engineering Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan Senior Councilor, Technical Coordination and Cooperation Division, Foundation for River Improvement and Restoration Tokyo, Japan Lecturer Musashi Institute of Technology Dept. of Civil Engineering Faculty of Engineering, Tokyo, Japan Abstract : About 50% of the population and 75% of the properties concentrate on the flood plain in Japan. The rivers have intimate relationship with our lives. Those conditions have been seen after modern river improvement projects that began about a century ago. The technology which was introduced from foreign countries was improved in conformity with geographical features and the climate condition of our nation, and has redeveloped as a Japanese original technology. In 1940's, Japan had serious natural disasters that were caused by large- scale typhoons. Those typhoons wiped out everything completely. Even though the government realized the importance of flood control and management after those natural disasters, civil work still aimed to economic development. Those construction works have become the one of factors for concentrating population and degrading natural environment in urban areas. Deterioration of river environment has become serious issue in urban development and main cause of pollution. The approaches for environmental restorations which were started about 30 years ago aimed to harmonize with nature environment and cities and human lives. There have been going on many projects called “river environmental improvement projects”, the “nature friendly river works” and “natural restoration projects.” The society has tried to find a way to live in harmony with nature. -

“Kidai Shoran”

“Kidai Shoran” What is the picture scroll Kidai Shoran? Kidai Shoran is a work that depicts a bird’s-eye view of the Nihonbashi street in Edo from the east side. It shows the main street between Nihonbashi and Imagawabashi (now, Chuo street) in 1805, over 200 years ago. e original is possessed by Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Although this excellent work is characterized by a warm sight and delicate touch, regrettably the name of the painter is unknown. e work vividly depicts 88 wholesale and retail stores, 1,671 people with various positions and jobs, 20 dogs, 13 horses, 4 cows, 1 monkey, 2 falcons, etc. Interesting scenes unfold one after another. e title Kidai Shoran seems to mean “an excellent scene of the great city of Edo in a glorious era.” It is just as if we slipped back in time to the Edo period. GUIDE TO THE EXHIBITIONS Regarding Kidai Shoran as a valuable work that will hand down the history and culture of Nihonbashi-street to future generations, the Nihonbashi-bridge Preservation Society and Committee for the 100-Year Renaissance Plan for Nihonbashi and Environs created and exhibited an about 17-meter copy of the picture scroll with the permission of Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin and under the general supervision of the Edo-Tokyo Museum. e picture part of the copy is 40% larger than that of the original. e copy has been printed on Japanese paper. e panel surrounding the picture shows explanations about the townspeople’s culture in the Edo period. -

Social Contribution of Environmental Conservation

Basis for Sustainable Environmental Management Social Contribution of Environmental Conservation We are making efforts to conserve global forest ecosystems and enhance our employees’ global citizen awareness. To conserve the global environment, it Three Areas of Environmentally-friendly Social Contribution Activities is important not only to reduce environ- mental impact, but also to maintain and enhance the self-recovery capability of the global environment. Ricoh is pro- Social contribution to Natural Resources moting forest ecosystem conservation environmental environment conservation projects at many places all over the Society world in partnership with environmental Ecosystem conservation activities We work to conserve ecosystems at the global and Resources NPOs and local communities. Further- community levels as a company and support more, manufacturing subsidiaries and organization engaged in such activities. Economy Resource Production activities recovery sales companies in various regions in the Promoting employees’ voluntary activities world are committed to environmentally- We promote employees’ participation in voluntary Money Products friendly social contribution activities. In activities for environmental conservation in communities and encourage them to reduce Japan, the Ricoh Group is implement- environmental impact at home and the workplace. Consumption activities ing an Environmental Volunteer Leader Increasing environmental awareness Tolerable impact We encourage individuals and organizations to Development Program* -

Tsurumi River ・Typical Urban River ・Class One River(一級河川) Tsurumi River ・Many Floods in Past ・ “Most Dirty” River in JAPAN

About the Tsurumi River ・Typical urban river ・Class One river(一級河川) Tsurumi River ・Many floods in past ・ “most dirty” river in JAPAN Information Tokyo Metropolis , City Tomohiro ATSUMI Kanagawa prefecture Kota ARAKI Length 42. 5 [km] Satoshi TOKUE Drainage Tomohiro MATSUKI 235 [km2] Keitaro MATSUMOTO basin SUZUKAKE_ DAI campus History of the Tsurumi river History of the Tsurumi river Frequently Flood - Before middle of Showa era Frequently Flood - Before middle of Showa era History of the Tsurumi river History of the Tsurumi river Water pollution – Urbanization Bad landscape – After store strengthening works What is the problem? Water Master Plan Present issues of Tsurumi river ・MdMade in 2004 • Flood of river that happens many times ・ To understand issues, manage and • Water pollution because of industrialization build facilities from the viewpoint of and urbanization good water cycle • Typical urban river ・All citizen bodies cooperate with each Needfd for comprehifldhensive flood contro l measures other “Tsurumi river basin water master plan” Water Master Plan IitdfInsisted of ma il5inly 5 par ts – Protect from floods – Recover clean and big river – Protect and keep environments – Take countermeasures in case of emergency – Come in contact alota lot http://www.ktr.mlit.go.jp/keihin/tsurumi/project/masterplan/02_ritsuan/01toha_image.htm Concrete Campaign Tsurumi River • Letʼs come in contact Multipurpose Retarding Basin • Campaign to take your rubbish home • Report about Tsurumi river Information LtiLocation KdkKodukue / TiToriyama area, Kohoku-ku, Yokohama Siz e 84 [ha] Capacity 3,900,000 [m3] Amount of About 300 flood 3 control [m /sec] Facilities Nissan Stadium soccer & baseball fields tennis court Tsurumi River Tsurumi River Multipurpose Retarding Basin Multipurpose Retarding Basin When the water level of the Tsurumi River reaches very high because of heavy rain, these areas ppgerform as the retarding basin. -

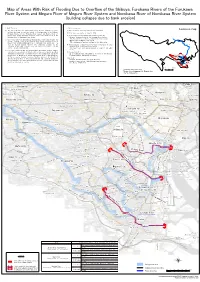

Map of Areas with Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Shibuya

Map of Areas With Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System (building collapse due to bank erosion) 1. About this map 2. Basic information Location map (1) This map shows the areas where there may be flooding powerful enough to (1) Map created by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government collapse buildings for sections subject to flood warnings of the Shibuya, (2) Risk areas designated on June 27, 2019 Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of Meguro River System and those subject to water-level notification of the (3) River subject to flood warnings covered by this map Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System. Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System (The flood warning section is shown in the table below.) (2) This river flood risk map shows estimated width of bank erosion along the Meguro River of Meguro River System Shibuya, Furukawa rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of (The flood warning section is shown in the table below.) Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System resulting from the maximum assumed rainfall. The simulation is based on the (4) Rivers subject to water-level notification covered by this map Sumida River situation of the river channels and flood control facilities as of the Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System time of the map's publication. (The water-level notification section is shown in the table below.) (3) This river flood risk map (building collapse due to bank erosion) roughly indicates the areas where buildings could collapse or be washed away when (5) Assumed rainfall the banks of the Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Up to 153mm per hour and 690mm in 24 hours in the Shibuya, Meguro River of Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River Furukawa, Meguro, Nomikawa Rivers basin Shibuya River,Furukawa River System are eroded. -

Flood Loss Model Model

GIROJ FloodGIROJ Loss Flood Loss Model Model General Insurance Rating Organization of Japan 2 Overview of Our Flood Loss Model GIROJ flood loss model includes three sub-models. Floods Modelling Estimate the loss using a flood simulation for calculating Riverine flooding*1 flooded areas and flood levels Less frequent (River Flood Engineering Model) and large- scale disasters Estimate the loss using a storm surge flood simulation for Storm surge*2 calculating flooded areas and flood levels (Storm Surge Flood Engineering Model) Estimate the loss using a statistical method for estimating the Ordinarily Other precipitation probability distribution of the number of affected buildings and occurring disasters related events loss ratio (Statistical Flood Model) *1 Floods that occur when water overflows a river bank or a river bank is breached. *2 Floods that occur when water overflows a bank or a bank is breached due to an approaching typhoon or large low-pressure system and a resulting rise in sea level in coastal region. 3 Overview of River Flood Engineering Model 1. Estimate Flooded Areas and Flood Levels Set rainfall data Flood simulation Calculate flooded areas and flood levels 2. Estimate Losses Calculate the loss ratio for each district per town Estimate losses 4 River Flood Engineering Model: Estimate targets Estimate targets are 109 Class A rivers. 【Hokkaido region】 Teshio River, Shokotsu River, Yubetsu River, Tokoro River, 【Hokuriku region】 Abashiri River, Rumoi River, Arakawa River, Agano River, Ishikari River, Shiribetsu River, Shinano -

The Geobiology and Ecology of Metasequoia

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/37160841 The Geobiology and Ecology of Metasequoia. Article · January 2005 Source: OAI CITATIONS READS 11 457 3 authors: Ben LePage Christopher J. Williams Pacific Gas and Electric Company Franklin and Marshall College 107 PUBLICATIONS 1,864 CITATIONS 55 PUBLICATIONS 1,463 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Hong Yang Massey University 54 PUBLICATIONS 992 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Conifer (Pinaceae and Cupressaceae (Taxodiaceae)) systematics and phylogeny View project All content following this page was uploaded by Ben LePage on 24 September 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Chapter 1 The Evolution and Biogeographic History of Metasequoia BEN A. LePAGE1, HONG YANG2 and MIDORI MATSUMOTO3 1URS Corporation, 335 Commerce Drive, Suite 300, Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, 19034, USA; 2Department of Science and Technology, Bryant University, 1150 Douglas Pike, Smithfield, Rhode Island, 02917, USA; 3Department of Earth Sciences, Chiba University, Yayoi-cho 133, Inage-ku, Chiba 263, Japan. 1. Introduction .............................................................. 4 2. Taxonomy ............................................................... 6 3. Morphological Stasis and Genetic Variation ................................. 8 4. Distribution of Metasequoia Glyptostroboides ............................... 10 5. Phytogeography ......................................................... -

Kanagawa Prefecture

www.EUbusinessinJapan.eu Latest update: August 2013 KANAGAWA PREFECTURE Prefecture’s flag Main City: Yokohama Population: 9,079,000 people, ranking 2/47 (2013) [1] Area: 2,415.84 km² [2] Geographical / Landscape description: Kanagawa Prefecture is located in the southern Kanto region of Japan and is part of the Greater Tokyo Area. Topographically, the prefecture consists of three distinct areas. The mountainous western region features the Tanzawa Mountain Range and Hakone Volcano. The hilly eastern region is characterized by the Tama Hills and Miura Peninsula. The central region, which surrounds the Tama Hills and Miura Peninsula, consists of flat stream terraces and low lands around major rivers including the Sagami River, Sakai River, Tsurumi River, and Tama River. [2] Climate: The climate is moderate due to the warm current running along the Pacific side of the archipelago. [2] Time zone: GMT +7 in summer (+8 in winter) International dialling code: 0081 Recent history, culture Kanagawa has played a major role in some significant periods in Japan's history. The first began in 1192, when the first military government was established in Kamakura. This made Kanagawa the centre of the Japanese political scene. The second period commenced in 1859, when the Port of Yokohama was opened to the world after more than 200 years of strict national isolation. Since then, Kanagawa became the gateway for the introduction of Western civilization. The third period was the 1950s, when the Japanese economy was being reconstructed after World War II. During this period, along with the development of the Keihin Industrial Belt, Kanagawa played a significant role in rebuilding the war-devastated Japanese economy. -

Cherry Blossom Tours Blossom Tours Japan 2019 Japan 2019

Cherry Blossom Tours Japan 2019 Version 2.02, Updated 13 November 2018 Japan Custom Tours Limited JapanCustomTours.Co.Nz 東京都Կӑ区区区歌ƞ伎ব222---252525 ---8 (8 ( スイーーート 411) Tokyo, Japan Cherry Blossom Tours Japan 2019 --- Tour Summaries YokosoYokoso————WelcomeWelcome Each cherry blossom (sakura) season is slightly different, the weather is the main driver of the blossom dates as spring ar- rives. In 2016 the cherry blossom season hit its peak in Kyoto and Tokyo at the end of March and beginning of April provid- ing some great displays. In2017, the season initially was fore- cast to be slightly early, but ended up a little late due to cold weather. The 2018 cherry blossom season was more than a week early in some locations and a few days early at others. Due to positive feedback from our guests we are repeating our core two-week cherry blossom tours that begin and end in To- kyo in each case. The first of these tours commences on March 17th with start dates of 31st March and 14th April for the other two. We have also designed a set of 10-day tours. These shorter trips include the flexibility to add additional days at the start or From here the tour is completed with the journey back to end of the trip, for those wanting extra free time in Tokyo or Tokyo. time to explore nearby locations. Classic Cherry Tour 30th March to The attached schedules indicate the dates for cherry blossom 14th April viewing in each location. These dates are based on the flower- ing times from the last ten years and are a guide only.