Theory and Practice: Kaesong and Inter-Korean Economic Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Korea Section 3

DEFENSE WHITE PAPER Message from the Minister of National Defense The year 2010 marked the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. Since the end of the war, the Republic of Korea has made such great strides and its economy now ranks among the 10-plus largest economies in the world. Out of the ashes of the war, it has risen from an aid recipient to a donor nation. Korea’s economic miracle rests on the strength and commitment of the ROK military. However, the threat of war and persistent security concerns remain undiminished on the Korean Peninsula. North Korea is threatening peace with its recent surprise attack against the ROK Ship CheonanDQGLWV¿ULQJRIDUWLOOHU\DW<HRQS\HRQJ Island. The series of illegitimate armed provocations by the North have left a fragile peace on the Korean Peninsula. Transnational and non-military threats coupled with potential conflicts among Northeast Asian countries add another element that further jeopardizes the Korean Peninsula’s security. To handle security threats, the ROK military has instituted its Defense Vision to foster an ‘Advanced Elite Military,’ which will realize the said Vision. As part of the efforts, the ROK military complemented the Defense Reform Basic Plan and has UHYDPSHGLWVZHDSRQSURFXUHPHQWDQGDFTXLVLWLRQV\VWHP,QDGGLWLRQLWKDVUHYDPSHGWKHHGXFDWLRQDOV\VWHPIRURI¿FHUVZKLOH strengthening the current training system by extending the basic training period and by taking other measures. The military has also endeavored to invigorate the defense industry as an exporter so the defense economy may develop as a new growth engine for the entire Korean economy. To reduce any possible inconveniences that Koreans may experience, the military has reformed its defense rules and regulations to ease the standards necessary to designate a Military Installation Protection Zone. -

Anniversary Battle of the Imjin River, Korean

70th Anniversary Friends of The of the Battle of the Imjin River, Korea 22nd – 25th April,1951 Welcome! The Museum will be able to open to visitors from 17th May 2021. The grounds at Alnwick Castle have been open since the end of March and it is a pleasure to see, and hear, visitors enjoying the venue once again. The Museum will have to wait a little longer before opening but our Front of House Team are looking forward to welcoming you soon! Cultural Recovery Fund Royal Northumberland Fusiliers The Museum is delighted to announce a in Korea, 1950-1951 successful bid for a share of the Arts Council’s government funded, Cultural Recovery Fund. After the defeat of the Japanese in the Second World War, Korea was divided into the The award of £25,000 will enable the Museum to communist North and the American-supported move forward after a challenging year and recover South. In June 1950 the North Koreans shortfalls caused by Covid-19. launched an invasion which threatened to overwhelm the South. The United Nations The Chairman of the Museum Trustees said: (founded in 1945) came to the defence of the South. The First Battalion, Royal Northumberland Fusiliers (1RNF) was “The Cultural Recovery Fund's award is great deployed to Korea as part of 29 Brigade, the news for us. We'll be opening on 17 May after UK's ground contribution to UN Forces. more than a year of shut-down, and the award means we can afford the staffing and the Initially the Government considered National precautions needed to welcome visitors safely. -

Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:21/01/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Democratic People's Republic of Korea INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: AN 1: JONG 2: HYUK 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. Title: Diplomat DOB: 14/03/1970. a.k.a: AN, Jong, Hyok Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) Passport Details: 563410155 Address: Egypt.Position: Diplomat DPRK Embassy Egypt Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0001 Date designated on UK Sanctions List: 31/12/2020 (Further Identifiying Information):Associations with Green Pine Corporation and DPRK Embassy Egypt (UK Statement of Reasons):Representative of Saeng Pil Trading Corporation, an alias of Green Pine Associated Corporation, and DPRK diplomat in Egypt.Green Pine has been designated by the UN for activities including breach of the UN arms embargo.An Jong Hyuk was authorised to conduct all types of business on behalf of Saeng Pil, including signing and implementing contracts and banking business.The company specialises in the construction of naval vessels and the design, fabrication and installation of electronic communication and marine navigation equipment. (Gender):Male Listed on: 22/01/2018 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13590. 2. Name 6: BONG 1: PAEK 2: SE 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: 21/03/1938. Nationality: Democratic People's Republic of Korea Position: Former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee,Former member of the National Defense Commission,Former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DPR0251 (UN Ref): KPi.048 (Further Identifiying Information):Paek Se Bong is a former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee, a former member of the National Defense Commission, and a former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID) Listed on: 05/06/2017 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13478. -

International Children's Day and Children's Union Foundation Day Tour

International Children's Day and Children's Union Foundation Day Tour May 31st – June 7th 2021 7 nights in North Korea + Beijing-Pyongyang travel time OVERVIEW There is a famous saying in North Korea that 'Children are the Kings of the Country' and significant attention is devoted to children's upbringing and education. International Children's Day on the 1st of June is particularly important and celebrations are held in recognition of children throughout North Korea. This is a day that is usually marked by student-oriented activities, events, and celebrations. We'll spend the holiday in the capital Pyongyang out and about in the city visiting locations popular with schoolchildren and their families, letting out our inner child and joining in the fun! During our time in Pyongyang, we will make sure to take you to the best that the country’s capital has to offer, including Kim Il Sung Square, the Juche Tower, and the Mansudae Grand Monument. Apart from Pyongyang, this tour will also visit historic Kaesong and the DMZ, the capital of the medieval Koryo Dynasty and the current North-South Korea border. Want to explore further? This tour will also get your across to the east coast of Korea to visit North Korea's second largest city of Hamhung, and the beachside city of Wonsan. You will then be back in Pyongyang to join in the 75th anniversary celebrations of the founding of the Children's Union, which is the children's membership section of the Worker's Party of Korea. THIS DOCUMENT CANNOT BE TAKEN INTO KOREA The Experts in Travel to Rather Unusual Destinations. -

Inter-Korean Maritime Dynamics in the Northeast Asian Context César Ducruet, Stanislas Roussin

Inter-Korean maritime dynamics in the Northeast Asian context César Ducruet, Stanislas Roussin To cite this version: César Ducruet, Stanislas Roussin. Inter-Korean maritime dynamics in the Northeast Asian context: Peninsular integration or North Korea’s pragmatism?. North / South Interfaces in the Korean Penin- sula, Dec 2008, Paris, France. halshs-00463620 HAL Id: halshs-00463620 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00463620 Submitted on 13 Mar 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Inter-Korean Maritime Dynamics in the Northeast Asian Context Peninsular Integration or North Korea’s Pragmatism? Draft paper International Workshop on “North / South Interfaces in the Korean Peninsula” EHESS, Paris, December 17-19, 2008 César DUCRUET1 Stanislas ROUSSIN Centre National de la Recherche General Manager & Head of Scientifique (CNRS) Research Department UMR 8504 Géographie-cités / SERIC COREE Equipe P.A.R.I.S. 1302 Byucksan Digital Valley V 13 rue du Four 60-73 Gasan-dong, Geumcheon-gu F-75006 Paris Seoul 153-801 France Republic of Korea Tel. +33 (0)140-464-000 Tel: +82 (0)2-2082-5613 Fax +33(0)140-464-009 Fax: +82 (0)2-2082-5616 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Abstract. -

Wonsan International Friendship Air Festival 3 Night Ex-Vladivostok Itinerary

WONSAN INTERNATIONAL FRIENDSHIP AIR FESTIVAL 3 NIGHT EX-VLADIVOSTOK ITINERARY Friday 22nd September 2017 to Monday 25th September 2017 Join us for what promises to be the highlight of the DPRK tourism calendar, Wonsan International Air Festival, 2017. This 3 night, time efficient long weekend tour allows people with limited time to see the two full days of the Air Festival, participating in all of the various activities, aerobatic displays and artistic performances. Day 1: Friday 22nd September 2017 1220 hrs: Depart Vladivostok aboard Air Koryo scheduled flight JS272 to Pyongyang (journey time approx. 1.5 hours). We recommend arriving 2 hours prior to departure to ensure plenty of time for customs and immigration formalities. 1245 hrs: Arrival at Pyongyang Sunan International Airport. Welcome to the DPRK! After entering the terminal, you will be escorted to another waiting Air Koryo aircraft that will whisk you onwards from Pyongyang to Wonsan in a mere 30 minutes. Here, at Wonsan Kalma International Airport, you will be met by your KITC guides and driven to Wonsan waterfront for a walk along the pier to Chondokdo lighthouse, a good chance to stretch your legs. It’s then time to check in at your accommodation, where a welcome dinner will be served. Day 2: Saturday 23rd September 2017 1st Day, Wonsan International Air Festival An exciting moment for everyone, as we kick off the Festival with a full day of thrilling aerobatic displays at Kalma Airport. The skies above will be filled with a mix of civilian airliners from Air Koryo and military aircraft from the Korean People’s Army Air Force. -

Mar 1968 - North Korean Seizure of U.S.S

Keesing's Record of World Events (formerly Keesing's Contemporary Archives), Volume 14, March, 1968 United States, Korea, Korean, Page 22585 © 1931-2006 Keesing's Worldwide, LLC - All Rights Reserved. Mar 1968 - North Korean Seizure of U.S.S. “Pueblo.” - Panmunjom Meetings of U.S. and North Korean Military Representatives. Increase in North Korean Attacks in Demilitarized Zone. - North Korean Commando Raid on Seoul. A serious international incident occurred in the Far East during the night of Jan. 22–23 when four North Korean patrol boats captured the 906-ton intelligence ship Pueblo, of the U.S. Navy, with a crew of 83 officers and men, and took her into the North Korean port of Wonsan. According to the U.S. Defence Department, the Pueblo was in international waters at the time of the seizure and outside the 12-mile limit claimed by North Korea. A broadcast from Pyongyang (the North Korean capital), however, claimed that the Pueblo–described as “an armed spy boat of the U.S. imperialist aggressor force” –had been captured with her entire crew in North Korean waters, where she had been “carrying out hostile activities.” The Pentagon statement said that the Pueblo “a Navy intelligence-collection auxiliary ship,” had been approached at approximately 10 p.m. on Jan. 22 by a North Korean patrol vessel which had asked her to identify herself. On replying that she was a U.S. vessel, the patrol boat had ordered her to heave to and had threatened to open fire if she did not, to which the Pueblo replied that she was in international waters. -

The Situation Further to Determine If External Assistance Is Needed

Information bulletin Democratic People’s Republic of Korea: Floods Information Bulletin n° 1 GLIDE n° FL-2013-000081-PRK 26 July 2013 Text box for brief photo caption. Example: In February 2007, the This bulletin is being issued for information Colombian Red Cross Society distributed urgently needed only, and reflects the current situation and materials after the floods and slides in Cochabamba. IFRC (Arial details available at this time. The 8/black colour) Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Red Cross Society (DPRK RCS), with the support of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) is assessing the situation further to determine if external assistance is needed. Since 12-22 July 2013, most parts of DPRK were hit by consecutive floods and landslides caused by torrential rains. As of 23 July, DPRK government data reports 28 persons dead, 2 injured and 18 missing. A total of 3,742 families have lost their houses due to total and partial destruction and 49,052 people have been displaced. Red Cross volunteers were mobilized for early Red Cross volunteers are distributing the relief items to flood affected people in Anju City, South Pyongan province. Photo: DPRK RCS. warning and evacuation, search and rescue, first aid service, damage and need assessment, and distribution of relief items. The DPRK RCS with the support of IFRC has released 2,690 emergency relief kits, including quilts, cooking sets, tarpaulins, jerry cans, hygiene kits and water purification tablets which were distributed to 10,895 beneficiaries in Tosan County, North Hwanghae province and Anju City, South Pyongan province. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

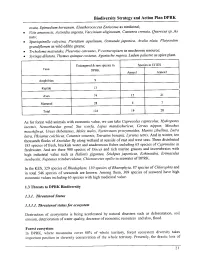

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood. -

Seismic Waves That Spread Through the Earth's Deep Interior

Seismic waves that spread through the Earth’s deep interior: BANG! or QUAKE! three stations at different distances from the sourc nces e ista 90º t d en er iff 60º d at s n o ti ta s e e r 30º h T CRUST (very thin) Seismic source CORE MANTLE 90º 60º 30º 90º 60º 30º 90º 60º 30º The wavefront position is shown after it has been traveling for several minutes. It continues to travel throughout the Earth's interior, bouncing off the core, and bouncing off the Earth's surface. 1.5 million seismic events since 1960, located by the International Seismological Centre on the basis of data from about 17,000 stations (up to ~ 6000 in any one year) 6L[GLIIHUHQWVWHSVLQQXFOHDUH[SORVLRQPRQLWRULQJ 'HWHFWLRQ GLGDSDUWLFXODUVWDWLRQGHWHFWDXVHIXOVLJQDO" $VVRFLDWLRQ FDQZHJDWKHUDOOWKHGLIIHUHQWVLJQDOVIURPWKHVDPH³HYHQW´" /RFDWLRQ ZKHUHZDVLW" ,GHQWLILFDWLRQ ZDVLWDQHDUWKTXDNHDPLQLQJEODVWDQXFOHDUZHDSRQWHVW" $WWULEXWLRQ LILWZDVDQXFOHDUWHVWZKDWFRXQWU\FDUULHGLWRXW" <LHOGHVWLPDWLRQ KRZELJZDVLW" MDJ 200 km HIA Russia 50°N 44°N HIA MDJ China USK BJT Chongjin 42° Japan 40° INCN KSRS MAJO 2006Oct09 MJAR Kimchaek SSE 30° 40° 120° 130° 140°E 126° 128° 130°E NIED seismic stations Hi-net 750 KiK-net 700 K-NET 1000 F-net 70 MDJ 200 km HIA Russia 50°N 44°N HIA MDJ China USK BJT Chongjin 42° Japan 40° INCN KSRS MAJO 2006Oct09 MJAR Kimchaek SSE 30° 40° 120° 130° 140°E 126° 128° 130°E Station Source crust mantle Pn - wave path (travels mostly in the mantle) Station Source crust mantle Pg - paths, in the crust, all with similar travel times Vertical Records at MDJ (Mudanjiang, -

Dpr Korea 2019 Needs and Priorities

DPR KOREA 2019 NEEDS AND PRIORITIES MARCH 2019 Credit: OCHA/Anthony Burke Democratic People’s Republic of Korea targeted beneficiaries by sector () Food Security Agriculture Health Nutrition WASH 327,000 97,000 CHINA Chongjin 120,000 North ! Hamgyong ! Hyeson 379,000 Ryanggang ! Kanggye 344,000 Jagang South Hamgyong ! Sinuiju 492,000 North Pyongan Hamhung ! South Pyongan 431,000 ! PYONGYANG Wonsan ! Nampo Nampo ! Kangwon North Hwanghae 123,000 274,000 South Hwanghae ! Haeju 559,000 REPUBLIC OF 548,000 KOREA PART I: TOTAL POPULATION PEOPLE IN NEED PEOPLE TARGETED 25M 10.9M 3.8M REQUIREMENTS (US$) # HUMANITARIAN PARTNERS 120M 12 Democratic People’s Republic of Korea targeted beneficiaries by sector () Food Security Agriculture Health Nutrition WASH 327,000 97,000 CHINA Chongjin 120,000 North ! Hamgyong ! Hyeson 379,000 Ryanggang ! Kanggye 344,000 Jagang South Hamgyong ! Sinuiju 492,000 North Pyongan Hamhung ! South Pyongan 431,000 ! PYONGYANG Wonsan ! Nampo Nampo ! Kangwon North Hwanghae 123,000 274,000 South Hwanghae ! Haeju 559,000 REPUBLIC OF 548,000 KOREA 1 PART I: TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: COUNTRY STRATEGY Foreword by the UN Resident Coordinator 03 Needs and priorities at a glance 04 Overview of the situation 05 2018 key achievements 12 Strategic objectives 14 Response strategy 15 Operational capacity 18 Humanitarian access and monitoring 20 Summary of needs, targets and requirements 23 PART II: NEEDS AND PRIORITIES BY SECTOR Food Security & Agriculture 25 Nutrition 26 Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) 27 Health 28 Guide to giving 29 PART III: ANNEXES Participating organizations & funding requirements 31 Activities by sector 32 People targeted by province 35 People targeted by sector 36 2 PART I: FOREWORD BY THE UN RESIDENT COORDINATOR FOREWORD BY THE UN RESIDENT COORDINATOR In the almost four years that I have been in DPR Korea Despite these challenges, I have also seen progress being made. -

Imjin70 Information Sheet What Is the Battle of Imjin River?

Imjin70 Information Sheet What is the battle of Imjin River? The battle of Imjin River was fought between the 22 – 25th of April 1951. The battle was part of a Chinese counter-offensive, after United Nations forces had recaptured Seoul in March 1951 The assault on ‘Gloster Hill’ was led by General Peng Dehuai who commanded a force of 300,000 troops attacking over a 40-mile sector. The 29th Independent Infantry Brigade group, under the command of Brigadier Tom Brodie, comprised of the 1st Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment, led by Lieutenant-Colonel J.P ‘Fred’ Carne, the 1st Royal Northumberland Fusiliers, 1st Royal Ulster Rifles, 8th King’s Royal Irish Hussars, C squadron 7th Royal Tank Regiment, 45th Field regiment Royal Artillery, 11th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery Royal Artillery, and 170th Battery Royal Artillery. The brigade was responsible for defending a 15-kilometre section of the front, over which General Peng Dehuai sent three divisions of his force. What resulted was the bloodiest battle that involved British troops in modern history since the Second World War. In the three-day battle, the Gloucestershire Regiment took the heaviest fire on 24th April 1951. In the early hours of the day, the ‘Glosters’ were forced to regroup and defend hill 235, now known as ‘Gloster Hill.’ That day an attempt was made to reinforce the Gloster’ position, but the Chinese military had now surrounded their position, and attempts to reinforce them were impossible. The 29th Independent Brigades mission became withdrawal. The other battalions retreated while the Glosters, Irish Fusiliers, and Ulster Riflemen repelled attack after attack.