Newsletter 15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maelor Mission Area Magazine

Maelor Mission Area Magazine Inside this issue: • Another (mostly) Good News Edition • Re-opening and recovering July 2020 • Scams Warning 75p per issue Rev’d Canon Sue Huyton Rector of Bangor on Dee Group of Parishes & Mission Area Leader The Rectory, 8 Ludlow Road Bangor-On-Dee Wrexham. LL13 0JG. Tel 01978 780608 [email protected] Rev’d Peter Mackriell Rector of Overton and Erbistock 07795 972325 The Rectory, 4 Sundorne, Overton, Wrexham. LL13 0EB Tel. 01978 710294 [email protected] Rev’d Clive Hughes Vicar of the Hanmer Group of Parishes The Vicarage, Hanmer, Whitchurch, Shropshire. SY13 3DE. Tel 01948 830468 [email protected] MMA Lay Chair: Mr. David Williams, [email protected] Magazine Editor: David Huyton, [email protected] The Maelor Churches are part of the Maelor Mission Area. This magazine has been published by volunteers for well over a century. During that time it has served various groupings of churches. We hope you find it informative, useful, and interesting. You are welcome to respond to any item. Please hand any such contribution to your Vicar. St Dunawd, Bangor on Dee. St Deiniol, Eyton St Deiniol, Worthenbury St Deiniol and St Marcella, Marchwiel St Mary the Virgin, Overton St Hilary, Erbistock St Chad, Hanmer St John the Baptist, Bettisfield Holy Trinity, Bronington St Mary Magdalene, Penley Mission Area News Dear Friends. I am sure that many of you will already have heard about a package of measures being put together to help Mission Areas weather the present financial crisis. As a response to the help we receive, we will be expected to enter a process of review. -

Management Plan 2014 - 2019

Management Plan 2014 - 2019 Part One STRATEGY Introduction 1 AONB Designation 3 Setting the Plan in Context 7 An Ecosystem Approach 13 What makes the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley Special 19 A Vision for the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley AONB 25 Landscape Quality & Character 27 Habitats and Wildlife 31 The Historic Environment 39 Access, Recreation and Tourism 49 Culture and People 55 Introduction The Clwydian Range and Dee lies the glorious Dee Valley Valley Area of Outstanding with historic Llangollen, a Natural Beauty is the dramatic famous market town rich in upland frontier to North cultural and industrial heritage, Wales embracing some of the including the Pontcysyllte country’s most wonderful Aqueduct and Llangollen Canal, countryside. a designated World Heritage Site. The Clwydian Range is an unmistakeable chain of 7KH2DȇV'\NH1DWLRQDO heather clad summits topped Trail traverses this specially by Britain’s most strikingly protected area, one of the least situated hillforts. Beyond the discovered yet most welcoming windswept Horseshoe Pass, and easiest to explore of over Llantysilio Mountain, %ULWDLQȇVȴQHVWODQGVFDSHV About this Plan In 2011 the Clwydian Range AONB and Dee Valley and has been $21%WRZRUNWRJHWKHUWRDFKLHYH was exteneded to include the Dee prepared by the AONB Unit in its aspirations. It will ensure Valley and part of the Vales of close collaboration with key that AONB purposes are being Llangollen. An interim statement partners and stake holders GHOLYHUHGZKLOVWFRQWULEXWLQJWR for this Southern extension including landowners and WKHDLPVDQGREMHFWLYHVRIRWKHU to the AONB was produced custodians of key features. This strategies for the area. in 2012 as an addendum to LVDȴYH\HDUSODQIRUWKHHQWLUH the 2009 Management Plan community of the AONB not just 7KLV0DQDJHPHQW3ODQLVGLHUHQW for the Clwydian Range. -

Aerial Archaeology Research Group - Conference 1996

AERIAL ARCHAEOLOGY RESEARCH GROUP - CONFERENCE 1996 PROGRAMM.E Wednesday 18 September 10.00 Registration 12.30 AGM 13.00 Lunch 114.00 Welcome and Introduction to Conference - Jo EIsworthIM Brown Aerial Archaeology in the Chester Area t'14.10 Archaeology in Cheshire and Merseyside: the view from the ground Adrian Tindall /14.35 The impact of aerial reconnaissance on the archaeology of Cheshire and Merseyside - Rob Philpot . {/15.05 Aerial reconnaissance in Shropshire; Recent results and changing perceptions Mike Watson 15.35 ·~ 5The Isle of Man: recent reconnaissance - Bob Bewley 15.55 Tea News and Views V16.l0 The MARS project - Andrew Fulton 16.4(}1~Introduction to GIS demonstrations 10/17.15 North Oxfordshire: recent results in reconnaissance - Roger Featherstone 17.30 Recent work in Norfolk - Derek Edwards 19.30 Conference Dinner 21 .30 The aerial photography training course, Hungary, June 1996 - Otto Braasch Historical Japan from the air - Martin Gojda Some problems from the Isle ofWight - David Motkin News and Views from Wales - Chris Musson Parchmarks in Essex - David Strachan Thursday 19 September International Session 9.00 From Arcane to Iconic - experience of publishing and exhibiting aerial photographs in New Zealand - Kevin Jones 9.40 The combined method of aerial reconnaissance and sutface collection - Martin Gojda "c j\ 10.00. Recent aerial reconnaissance in Po1and ·"Bf1uL,fi~./ 10.10'1 CtThirsty Apulia' 1994 - BaITi Jones 10.35 The RAPHAEL Programme of the European Union and AARG - Otto Braasch 10.45 Coffee 11.00 TechnicaJ -

Newsletter 16

Number 16 March 2019 Price £6.00 Welcome to the 16th edition of the Welsh Stone Forum May 11th: C12th-C19th stonework of the lower Teifi Newsletter. Many thanks to everyone who contributed to Valley this edition of the Newsletter, to the 2018 field programme, Leader: Tim Palmer and the planning of the 2019 programme. Meet:Meet 11.00am, Llandygwydd. (SN 240 436), off the A484 between Newcastle Emlyn and Cardigan Subscriptions We will examine a variety of local and foreign stones, If you have not paid your subscription for 2019, please not all of which are understood. The first stop will be the forward payment to Andrew Haycock (andrew.haycock@ demolished church (with standing font) at the meeting museumwales.ac.uk). If you are able to do this via a bank point. We will then move to the Friends of Friendless transfer then this is very helpful. Churches church at Manordeifi (SN 229 432), assuming repairs following this winter’s flooding have been Data Protection completed. Lunch will be at St Dogmael’s cafe and Museum (SN 164 459), including a trip to a nearby farm to Last year we asked you to complete a form to update see the substantial collection of medieval stonework from the information that we hold about you. This is so we the mid C20th excavations which have not previously comply with data protection legislation (GDPR, General been on show. The final stop will be the C19th church Data Protection Regulations). If any of your details (e.g. with incorporated medieval doorway at Meline (SN 118 address or e-mail) have changed please contact us so we 387), a new Friends of Friendless Churches listing. -

WRX4MOD the Flash

COMMUNITY : BRYMBO 1. Intended effect of To add a bridleway to the Definitive Map application. Geographical location 2. Grid references SJ 2663 5334 for the start and end SJ 2673 5389 of the claimed route. A map showing the claimed route is provided on the webpage, along with the original application 3. Address of any Graig Wen Farm property on which Brymbo Road the claimed route Bwlchgwyn lies. Wrexham LL11 5UB 4. Principal Nearest city: Chester cities/towns/villages nearest to the Nearest town: Wrexham claimed route. Nearest village : Bwlchgwyn 5. Locally-known The Flash name for location of the claimed route. 6. Community in Brymbo which the claimed route lies. Further information about the application 7. Applicant’s name Brymbo Community Council and address. 15 Chestnut Avenue Acton Wrexham LL12 7HS 8. Date application Received: 11 December 1994 received and accepted by Accepted: 11 December 1994 Wrexham County Borough Council. 9. Council contact details: (a) Claim reference WRX4/MOD – The Flash (b) Department Environment Department (c) Contact Definitive Map Team Rights of Way Abbey Road South Wrexham Industrial Estate Wrexham LL13 3BG Email: [email protected] Tel: 01978 292057 10. Date set for The Council will determine the application determination of the following the completion of an investigation of application. the available evidence and completion of consultations. 11. Details of any N/a appeal to the National Assembly to direct the Council to determine the application. 12. Date of Application determined 09 December 2010. determination of the application and Decision made to add restricted byway to the decision made. -

Planning Committee Meeting – 8Th February 2007

Planning Committee Meeting – 8th February 2007 2006/00062/FUL Received on 19 January 2006 Gateway Homes ( Wales) Ltd., C/o. 124, High Street, Barry, Vale of Glamorgan. , CF62 7DT Peter Jenkins Architects, 124, High Street, Barry, Vale of Glamorgan. , CF62 7DT Land adjacent to the Colcot Arms, Colcot Road, Barry Construction of 2 No. Town Houses SITE DESCRIPTION The application site relates to land adjacent to the Colcot Arms Public House, located at the northern end of Colcot Road near its junction with Port Road West, Barry. The application site comprises of a rectangular piece of land which currently serves the public house as open amenity space and is located between the recently laid out beer garden and lane adjacent to No. 192 Colcot Road which provides a footpath link between Hinchsliff Avenue and Colcot Road. The application site is a flat rectangular piece of grassed open space with a road frontage of 19 metres wide by a depth of 39 metres. DESCRIPTION OF DEVELOPMENT This is a full application and as amended now relates to two dwellings, comprising of detached modern hipped roof dwellings fronting and accessing onto Colcot Road. The proposed dwellings are of the same design and have a footprint of 12.8 metres by a width of 8.2 metres with an eaves height of 5 metres and ridge height of 7.7 metres. The dwellings will provide four bedroom accommodation and include an integral garage. The dwellings will be constructed in facing brick with contrasting brick courses and grey concrete interlocking roof tiles. The dwellings are set back some 12.5 metres from the edge of the highway and each dwelling has a rear garden of 18.5 metres and an area of 180 square metres. -

The Crick ( Pitch 2 )

Date: 21.07.2018 Ground: 38 Match: 4 (61) Venue: The Crick ( Pitch 2 ) Teams: Brymbo FC V Vauxhall Motors Reserves FC Competition: Pre-Season Friendly Admission: Free Entry Final Score: 2-1 ( H/T 1-0 ) Referee: Not Known Attendance: 30 ( Head Count ) Mileage to venue and return: 105 Miles Programme: NA Key Ring: £2 Village of Brymbo Brymbo, possibly from the Welsh ‘Bryn Baw’ ( Mud Hill or Dirt Hill ) is a local government community, part of Wrexham County Borough in North Wales. The population of the community including Brymbo Village and the villages of, Tanyfron and Bwlchgwyn plus several rural Hamlets is, 4836. Brymbo first makes an appearance in written documents as early as 1339, although the area was clearly occupied long before (read on for the discovery of ‘The Brymbo Man’) at this stage the area was a township. In 1410, The Burgesses of the nearby settlement of, Holt were given the rights to dig for Coal in the areas of, Harwd and Coedpoeth. Harwd, was an early name used for what is now Brymbo – this was derived from the English name, Harwood (Harewood) and referred to a common in one part of the township. During the 15th Century, Landowner, Edward ap Morgan ap Madoc constructed what was later to become Brymbo Hall and subsequently the home of his decendents, The Griffith Family. Following the rights given to the area for coal mining in 1410, the industry continued on a small scale. This was until an expansion in activity during the late 18th Century. The industrialist, John “Iron Mad” Wilkinson purchased Brymbo Hall and developed the estate, the development meant that mining for Coal and Ironstone could begin. -

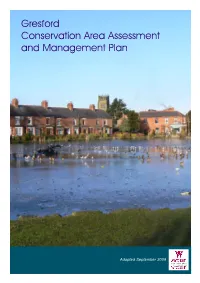

Gresford Conservation Area Assessment and Management Plan

Gresford Conservation Area Assessment and Management Plan Adopted September 2009 Contact For more information or advice contact: Chief Planning Officer Planning Department Wrexham County Borough Council Lambpit Street Wrexham LL11 1AR Telephone: 01978 292019 email: [email protected] www.wrexham.gov.uk/planning This document is available in welsh and in alternative formats on request. It is also available on the Council’s website Struck Pointing Pointing which leaves a small part of the top of the lower brick exposed Stringcourse Horizontal stone course or moulding projecting from the surface of the wall Tracery Delicately carved stonework usually seen gothic style windows Trefoil Three leaves, relating to any decorative element with the appearance of a clover leaf Tudor Period in English history from 1485 to 1603 References CADW Listing Descriptions Edward Hubbard, 1986. The Buildings of Wales (Denbighshire and Flintshire). Bethan Jones, 1997. All Saints Church Gresford. The Finest Parish Church in Wales. Dr Colin Jones, 1995. Gresford Village and Church and Royal Marford. Jones, 1868. Wrexham and its neighbourhood. A.N. Palmer, 1904. A History of the Old Parish of Gresford. Sydney Gardnor Jarman. The Parishes of Gresford and Hope: Past and Present. Gresford.All Saints'Church Gresford, Youth-Family Group, May 1993. The Wells of Gresford. Regional Sites and Monuments Record of the Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust. Guidance on Conservation Area Appraisals, English Heritage, 2005 Guidance on the Management of Conservation Areas, English -

Project Profile Castell Coch: Bat Survey & Licence Implementation

BSG ecology Project Profile Castell Coch: Bat Survey & Licence Implementation Background BSG Ecology has been providing ecological support The surveys identified a number of and advice to Cadw, the Welsh Government’s historic bat roosts within the site, with at least environment service, on a number of important projects in six species confirmed as roosting: common Wales since 2007. These have included the conservation and pipistrelle, soprano pipistrelle, brown long-eared bat, refurbishment of a number of historic buildings, including serotine, greater horseshoe bat and lesser horseshoe bat. Bishop’s Palace (St. David’s, Pembrokeshire), Coity Castle, As well as numerous locations supporting small numbers of Kidwelly Castle, Caerphilly Castle, Laugharne Castle, Beaupre roosting bats, we identified a breeding colony of brown long- Castle, Neath Abbey, Dinefwr Castle and Castell Coch. eared bats in the Kitchen Tower during the summer, and around thirty common pipistrelle bats hibernating behind Castell Coch is a Victorian Gothic Revival castle that is beams around the courtyard in the winter. managed and maintained by Cadw. This impressive structure contains a courtyard flanked by three four-storey towers Working closely with the clients and the construction with tall conical roofs: the Keep, Kitchen and Well Towers. team, BSG Ecology successfully devised mitigation and They each incorporate a series of apartment rooms, many method statements to ensure compliance with European of which are ornately decorated and furnished. The castle and domestic wildlife legislation, and secured a European walls are buttressed by a thick sloping stone wall that rises Protected Species (EPS) licence to carry out the conservation from the moat. -

Country Walks Around Wrexham

Country Walks around Wrexham Coedpoeth – Nant Mill Country Park – Clywedog Trail – Minera Lead Mines Country Park – Minera – Coedpoeth Approx 5 miles, 3 hours Directions to starting point by car From Wrexham town centre take the A525 Ruthin Road, cross over the A483 and follow the road for approx. 2 miles into Coedpoeth. Parking: There is a car park in Coedpoeth, situated just off the A525, opposite the New Inn. The car park can be accessed via the High Street or Park Road. Public Transport: Bus numbers 9 & 10 of G. Edwards & Son and numbers 10 & 11 of Arriva link Wrexham town centre to Coedpoeth. Timetables are available at the Tourist Information Centre, Libraries, online via Wrexham County Borough Council’s website and most Post Offices in Wrexham. Bus information: 01978 266166. It should be noted that this walk may be muddy and slippery in some places so please wear suitable footwear and take extra caution. This route is not suitable for wheelchairs or buggies. Please take the utmost care during this walk as some sections of the walk follow roads without pavements. WALK DIRECTIONS Starting from the car park opposite the New Inn in Coedpoeth, (Grid Ref: SJ 283511) walk out of the car park and turn left onto Park Road. After 200m, take the first left onto Tudor Street (the road in front of the black and white house), after a short distance take the next right opposite The Golden Lion. Approach Rock House and follow the footpath on the left eventually exiting once again on to Tudor Street. -

Scheduled Ancient Monuments in the Vale of Glamorgan

Scheduled Ancient Monuments in the Vale of Glamorgan Community Monument Name Easting Northing Barry St Barruch's Chapel 311930 166676 Barry Barry Castle 310078 167195 Barry Highlight Medieval House Site 310040 169750 Barry Round Barrow 612m N of Bendrick Rock 313132 167393 Barry Highlight Church, remains of 309682 169892 Barry Westward Corner Round Barrow 309166 166900 Barry Knap Roman Site 309917 166510 Barry Site of Medieval Mill & Mill Leat Cliffwood 308810 166919 Cowbridge St Quintin's Castle 298899 174170 Cowbridge South Gate 299327 174574 Cowbridge Caer Dynnaf 298363 174255 Cowbridge Round Barrows N of Breach Farm 297025 173874 Cowbridge Round Barrows N of Breach Farm 296929 173780 Cowbridge Round Barrows N of Breach Farm 297133 173849 Cowbridge Llanquian Wood Camp 302152 174479 Cowbridge Llanquian Castle 301900 174405 Cowbridge Stalling Down Round Barrow 301165 174900 Cowbridge Round Barrow 800m SE of Marlborough Grange 297953 173070 Dinas Powys Dinas Powys Castle 315280 171630 Dinas Powys Romano-British Farmstead, Dinas Powys Common 315113 170936 Ewenny Corntown Causewayed Enclosure 292604 176402 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291294 177788 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291260 177814 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291200 177832 Ewenny Ewenny Priory 291111 177761 Llancarfan Castle Ditches 305890 170012 Llancarfan Llancarfan Monastery (site of) 305162 170046 Llancarfan Walterston Earthwork 306822 171193 Llancarfan Moulton Roman Site 307383 169610 Llancarfan Llantrithyd Camp 303861 173184 Llancarfan Medieval House Site, Dyffryn 304537 172712 Llancarfan Llanvithyn -

From Maiden and Martyr to Abbess and Saint the Cult of Gwenfrewy at Gwytherin CYCS7010

Gwenfrewy the guiding star of Gwytherin: From maiden and martyr to abbess and saint The cult of Gwenfrewy at Gwytherin CYCS7010 Sally Hallmark 2015 MA Celtic Studies Dissertation/Thesis Department of Welsh University of Wales Trinity Saint David Supervisor: Professor Jane Cartwright 4 B lin a thrwm, heb law na throed, [A man exhausted, weighed down, without hand or A ddaw adreef ar ddeudroed; foot, Bwrw dyffon i’w hafon hi Will come home on his two feet. Bwrw naid ger ei bron, wedi; The man who throws his crutches in her river Byddair, help a ddyry hon, Will leap before her afterwards. Mud a rydd ymadroddion; To the deaf she gives help. Arwyddion Duw ar ddyn dwyn To the dumb she gives speech. Ef ai’r marw’n fyw er morwyn. So that the signs of God might be accomplished, A dead man would depart alive for a girl’s sake.] Stori Gwenfrewi A'i Ffynnon [The Story of St. Winefride and Her Well] Tudur Aled, translated by T.M. Charles-Edwards This blessed virgin lived out her miraculously restored life in this place, and no other. Here she died for the second time and here is buried, and even if my people have neglected her, being human and faulty, yet they always knew that she was here among them, and at a pinch they could rely on her, and for a Welsh saint I thinK that counts for much. A Morbid Taste for Bones Ellis Peters 5 Abstract As the foremost female saint of Wales, Gwenfrewy has inspired much devotion and many paeans to her martyrdom, and the gift of healing she was subsequently able to bestow.