Cultural Values, Religiosity and Gender Segregation by Field of Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formalism: from Racial Integration to Same-Sex Marriage Holning Lau

Hastings Law Journal Volume 59 | Issue 4 Article 2 1-2008 Formalism: From Racial Integration to Same-Sex Marriage Holning Lau Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Holning Lau, Formalism: From Racial Integration to Same-Sex Marriage, 59 Hastings L.J. 843 (2008). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol59/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Formalism: From Racial Integration to Same-Sex Marriage HOLNING LAU* Racial integration and same-sex marriage both headlined political and legal commentary during the summer of 2007. On one hand, the United States Supreme Court prompted discussion by holding, in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. i ("Parents Involved"),' that Seattle's and Louisville's voluntary efforts to integrate schools were unconstitutional On the other hand, commentators weighed in on litigation, legislation, and presidential candidates' platforms on same-sex marriage.' While racial integration and same-sex marriage captured attention, commentators typically addressed the two * Associate Professor, Hofstra University School of Law; Co-Director, Hofstra LGBT Rights Fellowship; 2oo6-2007 Harvey S. Shipley Miller Fellow, Williams Institute on Sexual Orientation Law and Public Policy, UCLA School of Law. This Article benefited from feedback that I received at the Hofstra Colloquium on Gender, Law, and Public Policy; the Williams Institute Works-in-Progress Series; the Emory Law School faculty workshop; and the Villanova Law School faculty workshop. -

Breaking the Binary: Desegregation of Bathrooms

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 36 Issue 2 Winter 2019-2020 Article 4 1-1-2020 Breaking the Binary: Desegregation of Bathrooms Timothy J. Graves Georgia State University College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Timothy J. Graves, Breaking the Binary: Desegregation of Bathrooms, 36 GA. ST. U. L. REV. 381 (2020). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol36/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Graves: Breaking the Binary: Desegregation of Bathrooms BREAKING THE BINARY: DESEGREGATION OF BATHROOMS Timothy J. Graves INTRODUCTION Sex discrimination is prohibited in the United States by several laws and constitutional guarantees.1 In recent years, the public bathroom has become a battleground for equal rights under these laws, both in the courts and the local legislature.2 Some states have attempted to legislate access to sex-segregated bathrooms purportedly based on biology, defining sex in a myriad of ways, which exclude gender-diverse individuals.3 Meanwhile, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has held that denying access to a bathroom corresponding with gender identity constitutes sex discrimination within the meaning of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.4 While the EEOC’s approach to bathroom access is a * J.D. -

Women in Islamic State: from Caliphate to Camps

ICCT Policy Brief October 2019 DOI: 10.19165/2019.03.9 ISSN: 2468-0656 Women in Islamic State: From Caliphate to Camps Author: Gina Vale Within the territorial boundaries of the Islamic State’s (IS) ‘caliphate’, women were largely confined to the domestic sphere. Their roles centred on support to militant husbands and the ideological upbringing of children. The physical collapse of IS’ proto-state marks a significant turning point in women’s commitment and activism for the group. Many IS-affiliated women are now indefinitely detained within Kurdish-run camps in North-eastern Syria. The harsh living conditions therein have fostered ideological divides. While some show signs of disillusionment with IS’ ‘caliphate’ dream, others have sought to re-impose its strictures. This paper contributes to the understanding of women’s roles across the lifespan of the Islamic State, and the efficacy of independent female activism to facilitate the group’s physical recovery. It argues that IS’ post-territorial phase has brought greater autonomy and ideological authority to individual hard-line detainees. However, beyond the camps, women’s influence and ability to realise IS’ physical resurgence remains practically limited and dependent on male leadership. Keywords: Islamic State, al-Hol, Women, Gender, Propaganda, Children, Indoctrination Women in Islamic State: From Caliphate to Camps Introduction The loss of Baghouz in March 2019 marked the long-awaited territorial collapse of Islamic State’s (IS, or ISIS) ‘caliphate’.1 As a result, Kurdish forces in Syria captured thousands of its remaining fighters and supporters, with many occupying camps such as al-Hol.2 Though once effective to initially detain and process IS-affiliated persons, the population of such camps now far exceeds maximum capacity. -

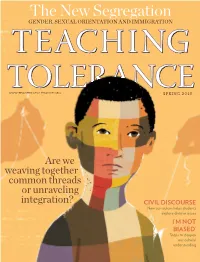

Teaching-Tolerance-Spring-2010.Pdf

The New Segregation GENDER, SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND IMMIGRATION tteeaacchihinngg ttwww.teachingtolerance.orgoolelerraannceceSpring 2010 Are we weaving together common threads or unraveling integration? CIVIL DISCOURSE new curriculum helps students explore divisive issues ‘I’M NOT BIASED’ steps to deepen our cultural understanding spring 2010 teaching tolerance I Our award-winning teaching KitS teaching tolerance makes copies of its educational kits available to educators are FREE tO SchoolS! free of charge. academy award ® academy award ® winner for winner for documentary documentary short subject short subject Starting Small This kit profiles exemplary pre-K through mighty timeS: the children’S march 3rd-grade classrooms in which peace, equity and justice are guiding themes. This Academy Award®-wining documentary film DVD only and accompanying resources tell the heroic story of One SurvivOr rememberS viva la cauSa the young people in Birmingham, Ala., who brought This Academy Award®-winning documentary film tells This short documentary film and accompanying segregation to its knees. Grade 5 and up. the empowering story of Holocaust survivor Gerda teacher’s guide explore one of the great DVD only Weissmann Klein. The kit includes primary documents movements for social justice in the u. S. — the drawn from Klein’s private collection, along with a Grape Strike and Boycott led by Cesar Chavez teacher’s guide and resource booklet. Grade 8 and up. and dolores Huerta. Grade 7 and up. DVD only DVD only Order theSe ready-made lesson KitS nOw! To receive a free copy of any two of these teaching kits, simply detach and RETURN THE ORDER CARD ON THIS PAGE, signed by a principal or department chair. -

Gender-Based Occupational Segregation in the 1990'S

InFocus Programme on Promoting the Declaration on Fundamental Principles WORK IN FREEDOM and Rights at Work International Labour Office Gender-based occupational segregation in the 1990’s R. Anker, H. Melkas and A. Korten DECLARATION/WP/16/2003 Working Paper Working WP.16 Working Paper Gender-based occupational segregation in the 1990s by Richard Anker Independent consultant, Geneva, Switzerland Helinä Melkas Research at Helsinki University of Technology Lahti Center, Finland and Ailsa Korten Independent consultant, Canberra, Australia International Labour Office September 2003 Foreword In June 1998 the International Labour Conference adopted the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and its Follow-up. The Declaration obligates all member States of the International Labour Organization to respect, promote and realize freedom of association and effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining, the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour, the effective abolition of child labour, and the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation1. The InFocus Programme on Promoting the Declaration is responsible for the reporting processes and technical cooperation activities associated with the Declaration Follow-up; and it carries out awareness-raising, advocacy and knowledge functions – of which this Working Paper is an example. Working Papers are intended to stimulate discussion of the issues covered by the Declaration. They express the views of the authors, which are not necessarily those of the ILO. The importance of occupational sex segregation as a form of discrimination is recognised in ILO Convention on Discrimination (Employment and Occupation), 1958 (No. 111). It is one of the most insidious aspects of gender inequality in the labour market, since it is generally accompanied by lower pay and worse working conditions in female occupations. -

The Overdue Case Against Sex-Segregated Bathrooms

The Overdue Case Against Sex-Segregated Bathrooms Laura Portuondot INTRODUCTION. ...................................... .............. 466 I. THE UNREVEALING HISTORY OF SEX-SEGREGATED BATHROOMS .............. 470 A. Origins ................................... ..... 471 B. Sex-Segregated Bathrooms and the ERA Debates ...... ...... 476 II. THE JURISPRUDENCE OF SEX-SEGREGATED BATHROOMS .. ............ 482 A. The Interest in Accommodating Biological Differences................483 B. The Interest in Protecting Privacy......... ................. 485 C. The Interest in Protecting Women's Safety .... ................... 491 III. THE LEGAL CASE AGAINST SEX-SEGREGATED BATHROOMS...................497 A. The Intermediate Scrutiny Standard .......... ........ 497 B. Applying Intermediate Scrutiny to the Judicially Asserted Interests ............................ .............. 499 1. Accommodating Biological Differences .......... .......... 499 2. Privacy . ..................................... 502 3. Safety ............................. .............. 510 IV. THE NORMATIVE CASE AGAINST SEX-SEGREGATED BATHROOMS .......... 514 A. When Separate May Be Equal: The Subordination Distinction.....514 B. Overcoming the Privacy Objection: Sex-Segregated Bathrooms Perpetuate Harmful Stereotypes ................ ...... 517 C. Overcoming the Safety Objection: Sex-Segregated Bathrooms Perpetuate Dangers for Women ................. ..... 521 f Yale Law School, J.D., expected 2018; Yale University, B.A., 2014. I am grateful and indebted to Professor Cary Franklin -

Occupational Segregation and Earnings Differences By

Research Summaries Occupational segregation factors such as workers' ages, education, and occupa- tional skill or status .' and earnings differences by sex Data and method NANCY F. RYTINA The data for this research are cross-tabulations from the 1976 Survey of Income and Education, which is be- The persistence of a wide male-female earnings dif- ing used as part of a continuing study on occupational ferential is well-documented . Through 1978, women sex segregation . The median 1975 annual earnings of listed who worked full time continued to earn about 60 per- men and women in all detailed occupations were cent as much as men .' Among the various explanations for workers grouped by age, race, and level of education offered to account for these differences, one suggested as approximate indicators of worker characteristics . The by a growing body of literature is that occupational sex percentage of women in each of the occupations was segregation plays a critical role.' The majority of work- calculated as a measure of occupational sex segregation . ing women are employed in a small number of occupa- In addition, the job characteristic of occupational status earnings tions which are predominantly female ; in both 1969 and is included to take into account variations in 1979, about one-half of all working women were between male and female occupations which arise from employed in fewer than 30 of the detailed Census occu- the concentration of female occupations in the middle are more dis- pations (in which 80 percent or more of the employees of the status hierarchy . Male occupations oc- were women) .3 Among the occupations heavily dominat- persed ; they include the highest paying professional ed by women are nurses, secretaries, and elementary cupations, as well as some of the very low paid service Socio-Economic school teachers . -

An Experimental Study of Sex Segregation in the Swedish Labour Market: Is Discrimination the Explanation?

IZA DP No. 3811 An Experimental Study of Sex Segregation in the Swedish Labour Market: Is Discrimination the Explanation? Magnus Carlsson Dan-Olof Rooth DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES DISCUSSION PAPER November 2008 Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor An Experimental Study of Sex Segregation in the Swedish Labour Market: Is Discrimination the Explanation? Magnus Carlsson Kalmar University Dan-Olof Rooth Kalmar University and IZA Discussion Paper No. 3811 November 2008 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post World Net. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. -

Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. 16-273 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States __________ GLOUCESTER COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, Petitioner, v. G.G., BY HIS NEXT FRIEND AND MOTHER, DEIRDRE GRIMM, Respondent. __________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit __________ BRIEF OF NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. AND THE ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT __________ SHERRILYN IFILL SUZANNE B. GOLDBERG Director-Counsel Counsel of Record JANAI NELSON Columbia Law School Sexuality CHRISTINA SWARNS and Gender Law Clinic MONIQUE LIN-LUSE 435 W. 116th St. DEUEL ROSS New York, NY 10027 NAACP Legal Defense & (212) 854-0411 Educational Fund, Inc. [email protected] 40 Rector St., Fl. 5 New York, NY 10006 PETER K. STRIS ELIZABETH BRANNEN DANA BERKOWITZ VICTOR O’CONNELL Stris & Maher LLP 725 S. Figueroa St., Ste. 1830 Counsel for Amici Curiae Los Angeles, CA 90017 (Additional Counsel On Inside Cover) COTY MONTAG JOHN PAUL SCHNAPPER- CASTERAS NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. 1444 I Street NW Washington, DC 20005 i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............................................. ii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ..................................... 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ........................................................................ 3 ARGUMENT ........................................................................ 6 I. THE PHYSICAL SEPARATION OF BATHROOMS BY RACE WAS CONTROVERSIAL AND HARMFUL ..................... 8 -

Gender and Race in Latin American Nineteenth-Century Travel

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Northern Sights: Gender and Race in Latin American Nineteenth-Century Travel Narratives of the United States DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Spanish by Linda Ruth Gruen Dissertation Committee: Professor Viviane Mahieux, Chair Professor Horacio Legras Professor Santiago Morales-Rivera 2020 © 2020 Linda Ruth Gruen, Spanish and Portuguese Review, Journeys: The International Journal of Travel and Travel Writing TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii VITA iv ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION v INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: The United States Man, Symbol of a Nation 21 CHAPTER 2: Women as a Transnational Marker of Modernity 71 CHAPTER 3: The United States as a Multiethnic Country 117 CONCLUSION 160 BIBLIOGRAPHY 171 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have been fortunate, as a student in the Spanish and Portuguese Department at the University of California, Irvine, to have received the invaluable mentorship of my academic advisor, Viviane Mahieux. I am also grateful for my committee members, Horacio Legras and Santiago Morales-Rivera, for their feedback and encouragement. I wish to thank my husband Lon, my madrina, and my fellow graduate students Blanca Liliana García and Aracelí Calderón, for their ongoing support during the ups and downs of my Ph.D. journey. I also thank the Spanish and Portuguese Review and Journeys: The International Journal of Travel and Travel Writing for permission to include portions of Chapters Two and Three of my dissertation. iii VITA Linda Ruth Gruen 1986 B.A. in Latin American Studies and Geography University of California, Berkeley 1987 Teaching Credential Program California State University, East Bay 2013 M.A. -

Women in Islamic Societies: a Selected Review of Social Scientific Literature

WOMEN IN ISLAMIC SOCIETIES: A SELECTED REVIEW OF SOCIAL SCIENTIFIC LITERATURE A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the Office of the Director of National Intelligence/National Intelligence Council (ODNI/ADDNIA/NIC) and Central Intelligence Agency/Directorate of Science & Technology November 2005 Author: Priscilla Offenhauer Project Manager: Alice Buchalter Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540−4840 Tel: 202−707−3900 Fax:202 −707 − 3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://www.loc.gov/rr/frd p 57 Years of Service to the Federal Government p 1948 – 2005 Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Women in Islamic Societies PREFACE Half a billion Muslim women inhabit some 45 Muslim-majority countries, and another 30 or more countries have significant Muslim minorities, including, increasingly, countries in the developed West. This study provides a literature review of recent empirical social science scholarship that addresses the actualities of women’s lives in Muslim societies across multiple geographic regions. The study seeks simultaneously to orient the reader in the available social scientific literature on the major dimensions of women’s lives and to present analyses of empirical findings that emerge from these bodies of literature. Because the scholarly literature on Muslim women has grown voluminous in the past two decades, this study is necessarily selective in its coverage. It highlights major works and representative studies in each of several subject areas and alerts the reader to additional significant research in lengthy footnotes. In order to handle a literature that has grown voluminous in the past two decades, the study includes an “Introduction” and a section on “The Scholarship on Women in Islamic Societies” that offer general observations⎯bird’s eye views⎯of the literature as a whole. -

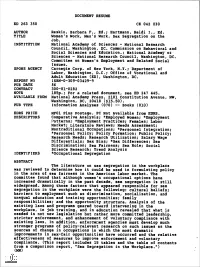

ED263350.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 263 350 CE 042 830 AUTHOR Reskin, Barbara F., Ed.; Hartmann, Heidi I., Ed. TITLE Women's Work, Men's Work. Sex Segregation on the Job. INSTITUTION National Academy of Sciences - National Research Council, Washington, DC. Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education.; National Academy of Sciences - National Research Council, Washington, DC. Committee on Women's Employment and Related Social Issues. SPONS AGENCY Carnegie Corp. of New York, N.Y.; Department of Labor, Washington, D.C.; Office of Vocational and Adult Education (ED), Washington, DC. REPORT NO ISBN-0-309-03429-9 PUB DATE 86 CONTRACT 300-81-0282 NOTE 185p.; For a related document, see ED 247 445. AVAILABLE FROMNational Academy Press, 2101 Constitution Avenue, NW, Washington, DC, 20418 ($15.50). PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) -- Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Comparative Analysis; *Employed Women; *Employment Patterns; *Employment Practices; Females; Labor Market; Literature Reviews; Needs Assessment; Nontraditional Occupations; *Personnel Integration; *Personnel Policy; Policy Formation; Public Policy; Research Needs; Research Utilization; Salary Wage Differentials; Sex Bias; *Sex Differences; Sex Discrimination; Sex Fairness; Sex Role; Social Science Research; Trend Analysis IDENTIFIERS *Occupational Segregation ABSTRACT The literature on sex segregation in the workplace was reviewed to determine how it could be used in formulating policy in the area of sex fairness in the American labor market. The committee found that although women's occupational options have increased dramatically in the past decade, sex segregation is still widespread. Among those factors that appeared responsible for sex segregation in the workplace were the following: cultural beliefs; barriers to employment such as discrimination, socialization, and unequal education and training opportunities; family responsibilities; and the opportunity structure.