Copyright by Jaya Kristin Soni 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National News in ‘09: Obama, Marriage & More Angie It Was a Year of Setbacks and Progress

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Dec. 30, 2009 • vol 25 no 13 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Joe.My.God page 4 LGBT Films of 2009 page 16 A variety of events and people shook up the local and national LGBT landscapes in 2009, including (clockwise from top) the National Equality March, President Barack Obama, a national kiss-in (including one in Chicago’s Grant Park), Scarlet’s comeback, a tribute to murder victim Jorge Steven Lopez Mercado and Carrie Prejean. Kiss-in photo by Tracy Baim; Mercado photo by Hal Baim; and Prejean photo by Rex Wockner National news in ‘09: Obama, marriage & more Angie It was a year of setbacks and progress. (Look at Joining in: Openly lesbian law professor Ali- form for America’s Security and Prosperity Act of page 17 the issue of marriage equality alone, with deni- son J. Nathan was appointed as one of 14 at- 2009—failed to include gays and lesbians. Stone als in California, New York and Maine, but ad- torneys to serve as counsel to President Obama Out of Focus: Conservative evangelical leader vances in Iowa, New Hampshire and Vermont.) in the White House. Over the year, Obama would James Dobson resigned as chairman of anti-gay Here is the list of national LGBT highlights and appoint dozens of gay and lesbian individuals to organization Focus on the Family. Dobson con- lowlights for 2009: various positions in his administration, includ- tinues to host the organization’s radio program, Making history: Barack Obama was sworn in ing Jeffrey Crowley, who heads the White House write a monthly newsletter and speak out on as the United States’ 44th president, becom- Office of National AIDS Policy, and John Berry, moral issues. -

One Year Out: an Assessment of DADT Repeal's Impact on Military

One Year Out: An Assessment of DADT Repeal’s Impact on Military Readiness by Professor Aaron Belkin, Ph.D, Palm Center Professor Morten Ender, Ph.D, US Military Academy* Dr. Nathaniel Frank, Ph.D, Columbia University Dr. Stacie Furia, Ph.D, Palm Center Professor George R. Lucas, Ph.D, US Naval Academy/Naval Postgraduate School* Colonel Gary Packard, Jr., Ph.D, US Air Force Academy* Professor Tammy S. Schultz, Ph.D, US Marine Corps War College* Professor Steven M. Samuels, Ph.D, US Air Force Academy* Professor David R. Segal, Ph.D, University of Maryland September 20, 2012 *The views expressed by faculty at US Government Agencies are those of the individuals and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of their respective Service Academies, their Service Branches, the Department of Defense or the US Government. Non-military institutional affiliations are listed for identification purposes only and do not convey the institutions’ positions. “Repeal… would undermine recruiting and retention, impact leadership at all levels, have adverse effects on the willingness of parents who lend their sons and daughters to military service, and eventually break the All-Volunteer Force.” — March 2009 statement signed by 1 1,167 retired admirals and generals “The flag and general officers for the military, 1,167 to date, 51 of them former four-stars, said that this law, if repealed, could indeed break the All-Volunteer Force. They chose that word very carefully. They have a lot of military experience… and they know what they’re talking about.” — Elaine Donnelly, Center for Military Readiness, May 20102 1 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................ -

Marches on Washington by Brett Genny Beemyn

Marches on Washington by Brett Genny Beemyn Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2004, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com The lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender rights movement in the United States grew tremendously during the last quarter of the twentieth century, a phenomenon perhaps best demonstrated by the success of the first three national marches held in Washington, D. C. Each march was much larger and more diverse than the previous one, as greater numbers of people became open about their sexual and gender identities and created a wide array of glbtq subcommunities. A less flattering trend was reflected in the fourth march: the increasing corporatization of the movement, with grassroots activists having less of a role in setting its goals and priorities. [However, the most recent march may have reversed this trend. Organized primarily by younger activists energized by the passage of Proposition 8, which nullified marriage equality in California, the emphasis of the October 2009 National Equality March was on grassroots activism.] The 1979 March Marking the tenth anniversary of the Stonewall riots and coming in the wake of the lenient jail sentence given to Dan White for the assassination of openly gay San Francisco city supervisor Harvey Milk, the First National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights on October 14, 1979 was an historic event that drew more than 100,000 people from across the United States and ten other countries. National lesbian and gay groups were initially reluctant to support the 1979 march, fearing that such a public display would not attract many people or, if it did, that it would generate a right-wing backlash similar to Anita Bryant's 1977 "Save Our Children" campaign. -

Alice Rossi (1922-2009): Feminist Scholar and an Ardent Activist

Volume 38 • Number 1 • January 2010 Alice Rossi (1922-2009): Feminist Scholar and an Ardent Activist by Jay Demerath, Naomi Gerstel, Harvard, the University of were other honors too: inside Michael Lewis, University of Chicago, and John Hopkins The Ernest W. Burgess Massachusetts - Amherst as a “research associate”—a Award for Distinguished position often used at the Research on the Family lice S. Rossi—the Harriet time for academic women (National Council of ASA’s 2010 Election Ballot Martineau Professor of Sociology 3 A married to someone in Family Relations, 1996); Find out the slate of officer and Emerita at the University of the same field. She did not the Commonwealth Award Massachusetts - Amherst, a found- committee candidates for the receive her first tenured for a Distinguished Career ing board member of the National 2010 election. appointment until 1969, in Sociology (American Organization for Women (NOW) Alice Rossi (1922-2009) when she joined the faculty Sociological Association, (1966-70), first president of at Goucher College, and her first 1989); elected American Academy of August 2009 Council Sociologists for Women in Society 5 appointment to a graduate depart- Arts and Sciences Fellow (1986); and Highlights (1971-72), and former president of the ment did not come until 1974, honorary degrees from six colleges Key decisions include no change American Sociological Association when she and her husband, Peter H. and universities. in membership dues, but (1982-83)—died of pneumonia on Rossi, moved to the University of As an original thinker, Alice man- subscription rates see a slight November 3, 2009, in Northampton, Massachusetts-Amherst as Professors aged to combine her successful activ- Massachusetts. -

Something Changed: the Social and Legal Status of Homosexuality in America As Reported by the New York Times Lauren Berard

Florida State University Libraries Honors Theses The Division of Undergraduate Studies 2014 Something Changed: The Social and Legal Status of Homosexuality in America as Reported by the New York Times Lauren Berard Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] 1 Abstract: (homosexual, law, culture) Homosexuality, though proven to be a naturally occurring phenomenon, has been a recurring subject of controversy: for years, homosexuality was classified as a disease, labeling gay citizen as sick at best, perverts at worst. As recently as fifty years ago, seen the best reception an active homosexual could hope for was to be seen as having a terrible affliction which must be cured. Gay citizens were treated as second-class citizens, with every aspect of their lifestyles condemned by society and the government. This thesis is a history of the changing social and legal status of homosexuality in the United States, from the 1920's. Something certainly has changed, in law and society, and I propose to explore the change and to explain why and how it happened. 2 THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF CRIMINOLOGY & CRIMINAL JUSTICE SOMETHING CHANGED: THE SOCIAL AND LEGAL STATUS OF HOMOSEXUALITY IN AMERICA AS REPORTED BY THE NEW YORK TIMES By LAUREN BERARD A thesis submitted to the Department of Criminology & Criminal Justice Theses and Dissertations In partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in the Major Degree Awarded: Spring, 2014 3 The members of the Defense Committee approve the thesis of Lauren Berard defended on May 2, 2014. -

Terrorizing Gender: Transgender Visibility and the Surveillance Practices of the U.S

Terrorizing Gender: Transgender Visibility and the Surveillance Practices of the U.S. Security State A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Mia Louisa Fischer IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Mary Douglas Vavrus, Co-Adviser Dr. Jigna Desai, Co-Adviser June 2016 © Mia Louisa Fischer 2016 Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my family back home in Germany for their unconditional support of my academic endeavors. Thanks and love especially to my Mom who always encouraged me to be creative and queer – far before I knew what that really meant. If I have any talent for teaching it undoubtedly comes from seeing her as a passionate elementary school teacher growing up. I am very thankful that my 92-year-old grandma still gets to see her youngest grandchild graduate and finally get a “real job.” I know it’s taking a big worry off of her. There are already several medical doctors in the family, now you can add a Doctor of Philosophy to the list. I promise I will come home to visit again soon. Thanks also to my sister, Kim who has been there through the ups and downs, and made sure I stayed on track when things were falling apart. To my dad, thank you for encouraging me to follow my dreams even if I chased them some 3,000 miles across the ocean. To my Minneapolis ersatz family, the Kasellas – thank you for giving me a home away from home over the past five years. -

Program Schedule

PROGRAM SCHEDULE FRIDAY, MAY 28, 2010 12:15 – 1:45 pm A01 A REPORT OF THE FIRST RSA CAREER RETREAT Co-Chairs: Cheryl Geisler, Simon Fraser University; Michael Halloran, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute; Krista Ratcliffe, Marquette University Participants: Jen Bacon, West Chester University; Suzanne Bordelon, San Diego State University; Elizabeth Britt, Northeastern University; Leah Ceccarelli, University of Washington; Martha Cheng, Rollins College; Janice Chernekoff, Kutztown University; Arabella Lyon, SUNY-Buffalo; Carole Clark Papper, Hofstra University; Barbara Schneider, University of Toledo; Christine Tully, University of Wisconsin, Madison; Liz Wright, Rivier College A02 BARACK OBAMA: THE RHETORIC OF A POSTMODERN PRESIDENT Chair: Connie Johnson, University of Texas at Austin A Tale of Two Cities: Obama at Howard and at South New Hampshire Sheena Howard, Howard University Cultural Memory and Productive Forgetting in Obama’s A More Perfect Union Speech G. Mitchell Reyes, Lewis and Clark College A More Perfect Union: A Critical Analysis of Obama’s "Race" Speech Matt Morris, University of Texas at Austin Barack Obama’s Heroic Whiteness: Invoking the Founding Fathers to Win the Presidency Connie Johnson, University of Texas at Austin Respondent : Barry Brummett, University of Texas at Austin A03 RHETORIC OF SCIENCE Chair: Virginia Anderson, Indiana University Southeast Raising Moral Questions through Science: Silent Spring’s Use of Narrative, Time, and Space Jessica Prody, University of Minnesota Evolving Concordance: An Aristotelian -

Guide to the Dennis Mcbride Collection on LGBTQ Las Vegas, Nevada

Guide to the Dennis McBride Collection on LGBTQ Las Vegas, Nevada This finding aid was created by Tammi Kim. This copy was published on March 25, 2021. Persistent URL for this finding aid: http://n2t.net/ark:/62930/f1vp61 © 2021 The Regents of the University of Nevada. All rights reserved. University of Nevada, Las Vegas. University Libraries. Special Collections and Archives. Box 457010 4505 S. Maryland Parkway Las Vegas, Nevada 89154-7010 [email protected] Guide to the Dennis McBride Collection on LGBTQ Las Vegas, Nevada Table of Contents Summary Information ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Scope and Contents Note ................................................................................................................................ 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................. 5 Related Materials ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Names and Subjects ....................................................................................................................................... -

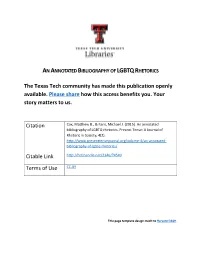

An Annotated Bibliography of Lgbtqrhetorics

AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF LGBTQ RHETORICS The Texas Tech community has made this publication openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters to us. Citation Cox, Matthew B., & Faris, Michael J. (2015). An annotated bibliography of LGBTQ rhetorics. Present Tense: A Journal of Rhetoric in Society, 4(2). http://www.presenttensejournal.org/volume-4/an-annotated- bibliography-of-lgbtq-rhetorics/ Citable Link http://hdl.handle.net/2346/74549 Terms of Use CC-BY Title page template design credit to Harvard DASH. An Annotated Bibliography of LGBTQ Rhetorics Matthew B. Cox and Michael J. Faris East Carolina University and Texas Tech University Present Tense, Vol. 4, Issue 2, 2015. http://www.presenttensejournal.org | [email protected] An Annotated Bibliography of LGBTQ Rhetorics Matthew B. Cox and Michael J. Faris Introduction The early 1970s marked the first publications both in English studies and communication studies to address lesbian and gay issues. In 1973, James W. Chesebro, John F. Cragan, and Patricia McCullough published an article in Speech Monographs exploring consciousness- raising by members of Gay Liberation. The following year, Louie Crew and Rictor Norton’s special issue on The Homosexual Imagination appeared in College English. In the four decades since these publications, the body of work in rhetorical studies within both fields that addresses lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (hereafter LGBTQ) issues has grown quite drastically. While the first few decades marked slow and interstitial development of this work, it has burgeoned into a rigorous, exciting, and diverse body of literature since the turn of the century—a body of literature that shows no signs of slowing down in its growth. -

Erin Rand's Curriculum Vitae

Erin J. Rand Department of Communication and Rhetorical Studies Syracuse University 100 Sims Hall Building V Syracuse, NY 13244-1230 E-mail: [email protected] Education Ph.D., Communication Studies, 2006 University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa Dissertation: “Risking Resistance: Rhetorical Agency in Queer Theory and Queer Activism” B.A., Psychology (minor in Spanish), 1996 Carroll College, Helena, Montana Summa cum Laude Academic Appointments Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York Associate Professor, Department of Communication and Rhetorical Studies, 2015- present. Assistant Professor, Department of Communication and Rhetorical Studies, 2009-2015. Affiliated Faculty, LGBT Studies Program, 2009-present. Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Communication Studies, Fall 2008-Summer 2009. California State University, Fresno, California Assistant Professor, Department of Communication, Fall 2006-Summer 2008. University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa Rand, Curriculum Vitae 2 Graduate Instructor, Department of Communication Studies, Spring 2005-Spring 2006. Teaching Assistant, Sexuality Studies Program, Spring 2004. Research Assistant, Sexuality Studies Program, Spring 2004. Graduate Instructor, Sexuality Studies Program, Fall 2003. Graduate Instructor, Department of Women’s Studies, Fall 2002-Spring 2003. Honors and Awards Excellence in Graduate Education Faculty Recognition Award, Syracuse University, 2017. Karl R. Wallace Memorial Award, National Communication Association, 2016. Book of the Year Award, -

Perry and the Lgbtq Movement

PERRY AND THE LGBTQ MOVEMENT MARY BERNSTEINt I. INTRODUCTION In order to discuss the ongoing impact of Hollingsworth v. Perryl on LGBTQ activism, it is important to first examine the impact of litigation on social movements more generally. Much of the literature on law and social movements is skeptical of the value of litigation for social movements.2 Some sociolegal scholars believe that social 3 movements squander time and money when they seek legal change. They argue that, by pursuing change through the courts, rather than through the political system, movements cede decision-making to lawyers, impair mobilization efforts, and make their missions more conservative.4 Even more problematic litigation may create backlash, as in the cases of Brown v. Board of Education and Roe v. Wade. Many question whether law and legal institutions can ever produce progressive social change given that the courts are unlikely to be much ahead of public opinion.7 In response, some sociolegal scholars counter that litigation can provide useful leverage for social movement organizations that are negotiating with opponents. Still others note that framing grievances in terms of legal rights can help to mobilize a constituency. For instance, a focus on legal rights has helped mobilize organizing against sex discrimination.9 Both the critiques and defenses of litigation in social movements share t Professor of Sociology, University of Connecticut. 1. Hollingsworth v. Perry, 81 U.S.L.W. 3075 (U.S. Dec. 7, 2012) (No. 12-144), granting cert. to Perry v. Brow, 671 F.3d 1052 (9th Cir. 2012), affg Perry v. Schwarzenegger, 704 F. -

Obama and the Gays by Claude J. Summers

Special Features Index Obama and the Gays Newsletter December 1, 2010 Sign up for glbtq's Obama and the Gays free newsletter to receive a spotlight by Claude J. Summers on GLBT culture every month. At the "Visible Vote 2008 Presidential e-mail address Forum" sponsored by the Human Rights Campaign and MTV's Logo cable television channel in August 2007, Melissa Etheridge recalled the subscribe euphoria many of us felt in 1992 at the privacy policy election of President Bill Clinton: "It unsubscribe was a very hopeful time for the gay community. For the first time we were Encyclopedia being recognized as American citizens. We were very, very Discussion go hopeful." But, she added, no doubt thinking of the Don't Ask, Don't Tell Act and the Defense of Marriage Act, both of which Tracy Baim's Obama and the became law under Clinton's watch, "In Gays (2010) is available in the years that followed, our hearts were paperback and Kindle formats. Baim also broken. We were thrown under the bus. maintains a website at We were pushed aside. All those great obamaandthegays.com. promises that were made to us were broken." Log In Now Two years into the Obama administration, many of us feel the same Forgot Your Password? way about our experience with the current President in whom we similarly invested so much time, energy, fortune, and emotion. Not a Member Yet? JOIN TODAY. IT'S FREE! On election night 2008, most of us believed that the gay movement had turned a significant corner with the election of an outspokenly glbtq-supportive President who was swept into office with large Democratic majorities in both Houses of Congress.