ACG Clinical Guideline: Evaluation of Abnormal Liver Chemistries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of Abnormal Liver Chemistries

ACG Clinical Guideline: Evaluation of Abnormal Liver Chemistries Paul Y. Kwo, MD, FACG, FAASLD1, Stanley M. Cohen, MD, FACG, FAASLD2, and Joseph K. Lim, MD, FACG, FAASLD3 1Division of Gastroenterology/Hepatology, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California, USA; 2Digestive Health Institute, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center and Division of Gastroenterology and Liver Disease, Department of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio, USA; 3Yale Viral Hepatitis Program, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112:18–35; doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.517; published online 20 December 2016 Abstract Clinicians are required to assess abnormal liver chemistries on a daily basis. The most common liver chemistries ordered are serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin. These tests should be termed liver chemistries or liver tests. Hepatocellular injury is defined as disproportionate elevation of AST and ALT levels compared with alkaline phosphatase levels. Cholestatic injury is defined as disproportionate elevation of alkaline phosphatase level as compared with AST and ALT levels. The majority of bilirubin circulates as unconjugated bilirubin and an elevated conjugated bilirubin implies hepatocellular disease or cholestasis. Multiple studies have demonstrated that the presence of an elevated ALT has been associated with increased liver-related mortality. A true healthy normal ALT level ranges from 29 to 33 IU/l for males, 19 to 25 IU/l for females and levels above this should be assessed. The degree of elevation of ALT and or AST in the clinical setting helps guide the evaluation. -

Total Bilirubin in Athletes, Determination of Reference Range

OriginalTotal bilirubin Paper in athletes DOI: 10.5114/biolsport.2017.63732 Biol. Sport 2017;34:45-48 Total bilirubin in athletes, determination of reference range AUTHORS: Witek K1, Ścisłowska J2, Turowski D1, Lerczak K1, Lewandowska-Pachecka S2, Corresponding author: Pokrywka A3 Konrad Witek Department of Biochemistry, Institute of Sport - National 1 Department of Biochemistry, Institute of Sport - National Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland Research Institute 2 01-982 Warsaw, Poland Faculty of Pharmacy with the Laboratory Medicine Division, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland 3 E-mail: Department of Biochemistry, 2nd Faculty of Medicine, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland [email protected] ABSTRACT: The purpose of this study was to determine a typical reference range for the population of athletes. Results of blood tests of 339 athletes (82 women and 257 men, aged 18-37 years) were retrospectively analysed. The subjects were representatives of different sports disciplines. The measurements of total bilirubin (BIT), iron (Fe), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) were made using a Pentra 400 biochemical analyser (Horiba, France). Red blood cell count (RBC), reticulocyte count and haemoglobin concentration measurements were made using an Advia 120 haematology analyser (Siemens, Germany). In groups of women and men the percentage of elevated results were similar at 18%. Most results of total bilirubin in both sexes were in the range 7-14 μmol ∙ L-1 (49% of women and 42% of men). The highest results of elevated levels of BIT were in the range 21-28 μmol ∙ L-1 (12% of women and 11% of men). There was a significant correlation between serum iron and BIT concentration in female and male athletes whose serum total bilirubin concentration does not exceed the upper limit of the reference range. -

Outcomes and Predictors of In-Hospital Mortality Among Cirrhotic

Turk J Gastroenterol 2014; 25: 707-713 Outcomes and predictors of in-hospital mortality among cirrhotic patients with non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in upper Egypt LIVER Khairy H Morsy1, Mohamed AA Ghaliony2, Hamdy S Mohammed3 1Department of Tropical Medicine and Gastroenterology, Sohag University Faculty of Medicine, Sohag, Egypt 2Department of Tropical Medicine and Gastroenterology, Assuit University Faculty of Medicine, Assuit, Egypt 3Department of Internal Medicine, Sohag University Faculty of Medicine, Sohag, Egypt ABSTRACT Background/Aims: Variceal bleeding is one of the most frequent causes of morbidity and mortality among cir- rhotic patients. Clinical endoscopic features and outcomes of cirrhotic patients with non-variceal upper gastroin- testinal bleeding (NVUGIB) have been rarely reported. Our aim is to identify treatment outcomes and predictors of in-hospital mortality among cirrhotic patients with non-variceal bleeding in Upper Egypt. Materials and Methods: A prospective study of 93 cirrhotic patients with NVUGIB who were admitted to the Original Article Tropical Medicine and Gastroenterology Department, Assiut University Hospital (Assiut, Egypt) over a one-year period (November 2011 to October 2012). Clinical features, endoscopic findings, clinical outcomes, and in-hospital mortality rates were studied. Patient mortality during hospital stay was reported. Many independent risk factors of mortality were evaluated by means of univariate and multiple logistic regression analyses. Results: Of 93 patients, 65.6% were male with a mean age of 53.3 years. The most frequent cause of bleeding was duodenal ulceration (26.9%). Endoscopic treatment was needed in 45.2% of patients, rebleeding occurred in 4.3%, and the in-hospital mortality was 14%. -

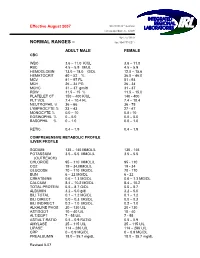

Normal Rangesа–А

Effective August 2007 5361 NW 33 rd Avenue Fort Lauderdale, FL 33309 954-777-0018 NORMAL RANGES – fax: 954-777-0211 ADULT MALE FEMALE CBC WBC 3.6 – 11.0 K/UL 3.6 – 11.0 RBC 4.5 – 5.9 M/UL 4.5 – 5.9 HEMOGLOBIN 13.0 – 18.0 G/DL 12.0 – 15.6 HEMATOCRIT 40 – 52 % 36.0 – 46.0 MCV 81 – 97 FL 81 93 MCH 26 – 34 PG 26 34 MCHC 31 – 37 gm/dl 31 37 RDW 11.5 – 15 % 11.5 – 15.0 PLATELET CT 150 – 400 K/UL 140 400 PLT VOL 7.4 – 10.4 FL 7.4 – 10.4 NEUTROPHIL % 36 – 66 36 75 LYMPHOCYTE % 23 – 43 27 47 MONOCYTE % 0.0 – 10 0.0 10 EOSINOPHIL % 0 – 5.0 0.0 – 5.0 BASOPHIL % 0 – 1.0 0.0 – 1.0 RETIC 0.4 – 1.9 0.4 – 1.9 COMPREHENSIVE METABOLIC PROFILE /LIVER PROFILE SODIUM 135 – 145 MMOL/L 135 145 POTASSIUM 3.5 – 5.5 MMOL/L 3.5 – 5.5 (OUTREACH) CHLORIDE 95 – 110 MMOL/L 95 110 CO2 19 – 34.MMOL/L 19 34 GLUCOSE 70 – 110 MG/DL 70 110 BUN 6 – 22 MG/DL 6 22 CREATININE 0.6 – 1.3 MG/DL 0.6 – 1.3 MG/DL CALCIUM 8.4 – 10.2 MG/DL 8.4 – 10.2 TOTAL PROTEIN 5.5 – 8.7 G/DL 5.5 – 8.7 ALBUMIN 3.2 – 5.0 g/dl 3.2 – 5.0 BILI TOTAL 0.1 – 1.2 MG/DL 0.1 – 1.2 BILI DIRECT 0.0 – 0.3 MG/DL 0.0 – 0.3 BILI INDIRECT 0.2 – 1.0 MG/DL 0.2 – 1.0 ALKALINE PHOS 20 – 130 U/L 20 130 AST/SGOT 10 – 40 U/L 10 40 ALT/SGPT 7 55 U/L 7 55 AST/ALT RATIO 0.5 – 0.9 RATIO 0.5 – 0.9 AMYLASE 25 – 115 U/L 25 – 115 U/L LIPASE 114 – 286 U/L 114 – 286 U/L CRP 0 – 0.9 MG/DL 0 – 0.9 MG/DL PREALBUMIN 18.0 – 35.7 mg/dL 18.0 – 35.7 mg/dL Revised 807 MAGNESIUM 1.8 – 2.4 mg/dL 1.8 – 2.4 mg/Dl LDH 100 – 200 Units /L 100 – 200 Units/L PHOSPHOROUS 2.3 – 5.0 mg/dL 2.3 – 5.0 mg/dL LACTIC ACID 0.4 -

Laboratory Test Reference Ranges

Laboratory Test Reference Ranges Central Zone Always refer to the laboratory report for appropriate reference ranges at the time of analysis. This document lists the test reference ranges that were established for the analysis methodologies used only by Nova Scotia Health Central Zone (Central Zone) Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine facilities. Anatomical Pathology Blood Tests Name of Test Specimen Units Low High Critical Type Anti-Cardiac Muscle Antibody Serum (SST) Qualitative N/A N/A N/A Anti-Skeletal Muscle Antibody Serum (SST) Qualitative N/A N/A N/A Anti-Pemphigoid Antibody Serum (SST) Qualitative N/A N/A N/A Anti-Pancreatic Islet Cell Antibody Serum (SST) Qualitative N/A N/A N/A Anti-Smooth Muscle Antibody Serum (SST) Qualitative N/A N/A N/A Anti-Liver Kidney Microsomal Antibody Serum (SST) Qualitative N/A N/A N/A Clinical Chemistry Blood Tests Name of Test Gender Age Units Low High Critical Acetaminophen M/F >0min µmol/L >350 Interpretive Data: Therapeutic range: 66-199 umol/L Toxic level: Refer to Rumack Matthew nomogram. Acetaminophen results can be falsely low for patients undergoing treatment of N- acetylcysteine (NAC). Adrenocorticotropic M/F >0min pmol/L 2.3 10.1 hormone Interpretive Data: Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) reference ranges are based on (ACTH) samples collected prior to 10 AM. Albumin M/F 0-1yr g/L 25 46 >1yr 35 50 Alcohol M/F >0min mmol/L None Detected >54 Interpretive Data: The method is intended for clinical purposes only. Medical-legal specimens should be analyzed by gas chromatographic method for confirmation of results. -

Inside the Minds: the Art and Science of Gastroenterology

Gastroenterology_ptr.qxd 8/24/07 11:29 AM Page 1 Inside the Minds ™ Inside the Minds ™ The Secrets to Success in The Art and Science of Gastroenterology Gastroenterology The Art and Science of Gastroenterology is an authoritative, insider’s perspective on the var- ious challenges in this field of medicine and the key qualities necessary to become a successful Top Doctors on Diagnosing practitioner. Featuring some of the nation’s leading gastroenterologists, this book provides a Gastroenterological Conditions, Educating candid look at the field of gastroenterology—academic, surgical, and clinical—and a glimpse Patients, and Conducting Clinical Research into the future of a dynamic practice that requires a deep understanding of pathophysiology and a desire for lifelong learning. As they reveal the secrets to educating and advocating for their patients when diagnosing their conditions, these authorities offer practical and adaptable strategies for excellence. From the importance of soliciting a thorough medical history to the need for empathy towards patients whose medical problems are not outwardly visible, these doctors articulate the finer points of a profession focused on treating disorders that dis- rupt a patient’s lifestyle. The different niches represented and the breadth of perspectives presented enable readers to get inside some of the great innovative minds of today, as experts offer up their thoughts around the keys to mastering this fine craft—in which both sensitiv- ity and strong scientific knowledge are required. ABOUT INSIDETHE MINDS: Inside the Minds provides readers with proven business intelligence from C-Level executives (Chairman, CEO, CFO, CMO, Partner) from the world’s most respected companies nationwide, rather than third-party accounts from unknown authors and analysts. -

Nutrition Considerations in the Cirrhotic Patient

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #204 NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #204 Carol Rees Parrish, MS, RDN, Series Editor Nutrition Considerations in the Cirrhotic Patient Eric B. Martin Matthew J. Stotts Malnutrition is commonly seen in individuals with advanced liver disease, often resulting from a combination of factors including poor oral intake, altered absorption, and reduced hepatic glycogen reserves predisposing to a catabolic state. The consequences of malnutrition can be far reaching, leading to a loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength, a variety of micronutrient deficiencies, and poor clinical outcomes. This review seeks to succinctly describe malnutrition in the cirrhosis population and provide clarity and evidence-based solutions to aid the bedside clinician. Emphasis is placed on screening and identification of malnutrition, recognizing and treating barriers to adequate food intake, and defining macronutrient targets. INTRODUCTION The Problem ndividuals with cirrhosis are at high risk of patients to a variety of macro- and micronutrient malnutrition for a multitude of reasons. Cirrhotic deficiencies as a consequence of poor intake and Ilivers lack adequate glycogen reserves, therefore altered absorption. these individuals rely on muscle breakdown as an As liver disease progresses, its complications energy source during overnight periods of fasting.1 further increase the risk for malnutrition. Large Well-meaning providers often recommend a variety volume ascites can lead to early satiety and decreased of dietary restrictions—including limitations on oral intake. Encephalopathy also contributes to fluid, salt, and total calories—that are often layered decreased oral intake and may lead to inappropriate onto pre-existing dietary restrictions for those recommendations for protein restriction. -

Medical History and Primary Liver Cancer1

[CANCER RESEARCH 50, 6274-6277. October I. 1990] Medical History and Primary Liver Cancer1 Carlo La Vecchia, Eva Negri, Barbara D'Avanzo, Peter Boyle, and Silvia Franceschi Istituto di Ricerche Farmaco/logiche "Mario Negri," 20157 Milan, Italy [C. L. V., E. N., B. D.]; Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland ¡C.L. V.¡;Unitof Analytical Epidemiology, The International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France ¡P.B.f;and Servizio di Epidemiologia, Centro di Riferimento Oncologico, 33081 Ariano (PN), Italy [S. F.] ABSTRACT The general structure of this investigation has already been described (12). Briefly, trained interviewers identified and questioned cases and The relationship between selected aspects of medical history and the controls in the major teaching and general hospitals of the Greater risk of primary liver cancer was analyzed in a hospital-based case-control Milan area. The structured questionnaire included information on study conducted in Northern Italy on 242 patients with histologically or sociodemographic characteristics, smoking habits, alcohol drinking, serologically confirmed hepatocellular carcinoma and 1169 controls in intake of coffee and 14 selected indicator foods, and a problem-oriented hospital for acute, nonneoplastic, or digestive diseases. Significant asso medical history including 12 selected diseases or interventions. By ciations were observed for clinical history of hepatitis (odds ratio (OR), definition, the diseases or interventions considered had to anticipate by 3.7; 95% confidence interval (CI), 2.3-5.9], cirrhosis (OR, 16.8; 95% CI, at least 1 year the onset of the symptoms of the disease which led to 9.8-28.8), and three or more episodes of transfusion in the past (OR, admission. -

Abnormal Liver Enzymes

Jose Melendez-Rosado , MD Ali Alsaad , MBChB Fernando F. Stancampiano , MD William C. Palmer , MD 1.5 ANCC Contact Hours Abnormal Liver Enzymes ABSTRACT Abnormal liver enzymes are frequently encountered in primary care offi ces and hospitals and may be caused by a wide variety of conditions, from mild and nonspecifi c to well-defi ned and life-threatening. Terms such as “abnormal liver chemistries” or “abnormal liver enzymes,” also referred to as transaminitis, should be reserved to describe infl am- matory processes characterized by elevated alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and alkaline phosphatase. Although interchangeably used with abnormal liver enzymes, abnormal liver function tests specifi cally denote a loss of synthetic functions usually evaluated by serum albumin and prothrombin time. We discuss the entities that most commonly cause abnormal liver enzymes, specifi c patterns of enzyme abnormalities, diagnostic modalities, and the clinical scenarios that warrant referral to a hepatologist. he liver is the largest solid organ in the human elevated liver function tests (LFTs), they would more body, as well as one of the most versatile. It accurately describe as liver inflammation tests. LFTs manufactures cholesterol, contributes to hor- should instead refer to serum assessments of hepatic mone production, stores glucose in the form synthetic function, such as albumin and prothrombin Tof glycogen, processes drugs prior to systemic exposure, time. Disease categories, such as viral inflammation and and aids in the digestion of food and production of injury from alcohol use, may be differentiated by fol- proteins. However, the liver is also vulnerable to injury, lowing patterns and trends of enzyme elevations. -

Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia

Clinical Chemistry Trainee Council Pearls of Laboratory Medicine www.traineecouncil.org TITLE: Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia PRESENTER: Linnea M. Baudhuin, Ph.D., DABMG Slide 1: Title slide Slide 2: Bilirubin is an orange‐yellow pigment derived from the degradation of the heme moiety of hemoproteins, particularly the hemoglobin of mature circulating erythrocytes. Hemo oxygenase is the enzyme initially responsible for the degradation of hemoglobin, producing biliverdin and carbon monoxide. Biliverdin reductase reduces the green‐pigmented biliverdin to bilirubin. Bilirubin production primarily occurs in the liver, but also can occur in the spleen and bone marrow, and as it is produced in the unconjugated form, bilirubin is highly insoluble. Bilirubin is conjugated in the liver, which allows excretion in the bile and urine. Bilirubin is mainly conjugated to glucuronic acid by uridine diphosphate glucuronosyl transferase 1A1, or UGT1A1. Slide 3: Bilirubin is photosensitive because light causes configurational and structural changes to unconjugated bilirubin. The structure of bilirubin, as established by x‐ray crystallography, is a ridge‐tiled configuration stabilized by six intramolecular hydrogen bonds. These six intramolecular hydrogen bonds stabilize the Z‐Z structure of unconjugated bilirubin, rendering it insoluble. Rotation and/or breakage of the bonds on carbon atoms 5 and 15 lead to more open E‐Z‐ and Z‐E‐bilirubin structures, which are more water soluble. The sensitivity of bilirubin to light is the basis for phototherapy in individuals with unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Clinical measurement of bilirubin can also be affected due to this light sensitivity. Slide 4: Four fractions of bilirubin can be revealed upon open‐column chromatographic separation that does not involve deproteinization. -

Liver Function Tests in Type 2 Sudanese Diabetic Patients

International Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism Vol. 3(2) pp. 17-21, February 2011 Available online http://www.academicjournals.org/ijnam ISSN 2141-2340 ©2011 Academic Journals. Full Length Research Paper Liver function tests in type 2 Sudanese diabetic patients Ayman S. Idris 1*, Koua Faisal Hammad Mekky 1, Badr Eldin Elsonni Abdalla 2 and Khalid Altom Ali 3 1Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science and Technology, Al-Neelain University, P. O. Box 12702, Al Baladya St. Khartoum, Sudan. 2Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Gezira, Sudan. 3Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, International University of Africa, Sudan. Accepted 21 January, 2011 This study was planned to evaluate the liver function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus by measuring aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), total protein and albumin. The study was carried out in Wad Medani, Abo Agla Diabetes Centre. 50 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (23 male and 27 female) were included in the study. Their ages ranged between 43 and 79 years. Thirty matched normal individuals were taken as control group. In the present study, mean values of ALT, AST and GGT were significantly higher in patients than in the control (P<0.001). Total protein and albumin concentrations in patients were lower compared to control group (P<0.01). The mean of serum glucose in patients revealed significant difference (P<0.000) in comparison to the control group. Although the differences were statistically significant, the means of ALT, AST, GGT, total protein and albumin were falling within the normal range. -

Inherited Thrombophilia Protein S Deficiency

Inherited Thrombophilia Protein S Deficiency What is inherited thrombophilia? If other family members suffered blood clots, you are more likely to have inherited thrombophilia. “Inherited thrombophilia” is a condition that can cause The gene mutation can be passed on to your children. blood clots in veins. Inherited thrombophilia is a genetic condition you were born with. There are five common inherited thrombophilia types. How do I find out if I have an They are: inherited thrombophilia? • Factor V Leiden. Blood tests are performed to find inherited • Prothrombin gene mutation. thrombophilia. • Protein S deficiency. The blood tests can either: • Protein C deficiency. • Look at your genes (this is DNA testing). • Antithrombin deficiency. • Measure protein levels. About 35% of people with blood clots in veins have an inherited thrombophilia.1 Blood clots can be caused What is protein S deficiency? by many things, like being immobile. Genes make proteins in your body. The function of Not everyone with an inherited thrombophilia will protein S is to reduce blood clotting. People with get a blood clot. the protein S deficiency gene mutation do not make enough protein S. This results in excessive clotting. How did I get an inherited Sometimes people produce enough protein S but the thrombophilia? mutation they have results in protein S that does not Inherited thrombophilia is a gene mutation you were work properly. born with. The gene mutation affects coagulation, or Inherited protein S deficiency is different from low blood clotting. The gene mutation can come from one protein S levels seen during pregnancy. Protein S levels or both of your parents.