Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Genealogy of the Pepys Family, 1273-1887

liiiiiiiw^^^^^^ UGHAM YOUM; university PROVO, UTAH ^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Brigham Young University http://www.archive.org/details/genealogyofpepysOOpepy ^P?!pPP^^^ GENEALOGY OF THE PEPYS FAMILY. r GENEALOGY OF THE PEPYS FAMILY 1273— 1887 COMPILED BY WALTER COURTENAY PEPYS LATE LIEUTENANT 60TH ROYAL RIFLES BARRISTER-AT-LAW, LINCOLN'S INN LONDON GEORGE BELL AND SONS, YORK STREET COVENT GARDEN I 1887 CHISWICK PRESS :—C. WHITTINGHAM AND CO., TOOKS COURT CHANCERY LANE. 90^w^ M ^^1^^^^K^^k&i PREFACE. N offering the present compilation of family data to those interested, I wish it to be clearly understood that I claim to no originality. It is intended—as can readily be seen by those who . read it—to be merely a gathering together of fragments of family history, which has cost me many hours of research, and which I hope may prove useful to any future member of the family who may feel curious to know who his forefathers were. I believe the pedigrees of the family I have compiled from various sources to be the most complete and accurate that ever have been published. Walter Courtenay Pepys. 6l, PORCHESTER TeRRACE, London, W., /uly, 1887. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAGE 1. Arms of the Family, &c. 9 2. First Mention of the Name 1 3. Spelling and Pronunciation of the Name . .12 4. Foreign Form of the Name . 14 5. Sketch of the Family Histoiy 16 6. Distinguished Members of the Family 33 7. Present Members of the Family 49 8. Extracts from a Private Chartulary $2 9. -

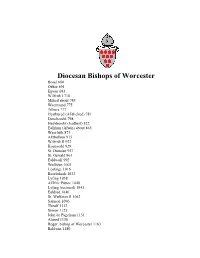

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester Bosel 680 Oftfor 691 Egwin 693 Wilfrith I 718 Milred about 743 Waermund 775 Tilhere 777 Heathured (AEthelred) 781 Denebeorht 798 Heahbeorht (Eadbert) 822 Ealhhun (Alwin) about 845 Waerfrith 873 AEthelhun 915 Wilfrith II 922 Koenwald 929 St. Dunstan 957 St. Oswald 961 Ealdwulf 992 Wulfstan 1003 Leofsige 1016 Beorhtheah 1033 Lyfing 1038 AElfric Puttoc 1040 Lyfing (restored) 1041 Ealdred 1046 St. Wulfstan II 1062 Samson 1096 Theulf 1113 Simon 1125 John de Pageham 1151 Alured 1158 Roger, bishop of Worcester 1163 Baldwin 1180 William de Narhale 1185 Robert Fitz-Ralph 1191 Henry de Soilli 1193 John de Constantiis 1195 Mauger of Worcester 1198 Walter de Grey 1214 Silvester de Evesham 1216 William de Blois 1218 Walter de Cantilupe 1237 Nicholas of Ely 1266 Godfrey de Giffard 1268 William de Gainsborough 1301 Walter Reynolds 1307 Walter de Maydenston 1313 Thomas Cobham 1317 Adam de Orlton 1327 Simon de Montecute 1333 Thomas Hemenhale 1337 Wolstan de Braunsford 1339 John de Thoresby 1349 Reginald Brian 1352 John Barnet 1362 William Wittlesey 1363 William Lynn 1368 Henry Wakefield 1375 Tideman de Winchcomb 1394 Richard Clifford 1401 Thomas Peverell 1407 Philip Morgan 1419 Thomas Poulton 1425 Thomas Bourchier 1434 John Carpenter 1443 John Alcock 1476-1486 Robert Morton 1486-1497 Giovanni De Gigli 1497-1498 Silvestro De Gigli 1498-1521 Geronimo De Ghinucci 1523-1533 Hugh Latimer resigned title 1535-1539 John Bell 1539-1543 Nicholas Heath 1543-1551 John Hooper deprived of title 1552-1554 Nicholas Heath restored to title -

Journal of the KILVERT SOCIETY

THE Journal OF THE KILVERT SOCIETY Number 41 September 2015 THE KILVERT SOCIETY Founded in 1948 to foster an interest in the Reverend Francis Kilvert, his work, his Diary and the countryside he loved Registered Charity No. 1103815 www.thekilvertsociety. org.uk President Ronald Blythe FRSL Vice-Presidents Mrs S Hooper, Mr A L Le Quesne Hon Life Members Miss M R Mumford, Mrs Hurlbutt, Mrs T Williams, Mr J Palmer, Dr W Mom Lockwood, Mr J Hughes-Hallett Chairman David Elvins Dates for your diary Sandalwood, North End Road, Steeple Claydon, Bucks MK18 2PG. All teas and pub lunches must be pre booked with the Secretary by post or email (jeanbrimson @hotmail.com) Hon Secretary Alan Brimson Saturday 26 September 30 Bromley Heath Avenue, Downend, Bristol BS16 6JP. 12.30pm Meet at church of St James, Kinnersley, for a email: jeanbrimson @hotmail.com picnic lunch, followed by a conducted tour of Kinnersley Castle. Tea provided by the castle, £7.50. Vice-Chairman Michael Sharp The Old Forge, Kinnersley, Herefordshire HR3 6QB. Sunday 27 September 3pm Commemorative Service at St James’ Church, Hon Treasurer Richard Weston Kinnersley, followed by tea and croquet on the lawn at 35 Harold Street, Hereford HR1 2QU. the Rectory, by kind invitation of Major and Mrs James Greenfield. £4.50 per person. Hon Membership Secretary Mrs Sue Rose Seend Park Farm, Semington, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Tea on both days must be booked with the Secretary by BA14 6LH. Friday 18 September. Hon Publications Manager and Archivist Colin Dixon 2016 Tregothnan, Pentrosfa Crescent, Llandrindod Wells, Powys LD1 5NW. -

Wo.Rbestensliir1t. [.K:Ettfs

Wo.RbEstEnsliiR1t. [.K:EttfS I t n 1 fle\-racrd' ITltm~,iai'ther~llla:c,HHfr~eD.tl rt.oCk'G~org'E!~ i'arcier'; 'to~~lt faltttt '• ' 1'otnpldh~ Renry, ta.?fuiet', M~ Gould Henry, farmer, :Priest~ela 31 ' Mellor Geot'ge ~.farmer,Merebrdok frm 't'nrnel' Williath, rriarket1' 'g"t'tlen#. 1 1 1 Green Francis, fall-mer; Sinlt'"fatiri ~ • • Merrlck Alfl'etl, ~amekeeP.eY to J. V. Vicata.,.e house •l ' 1 ''•" ,r1J1 Green Sl. district surveyor, Walmer vil Hornyold esq. Blackmore l!a.tk · ' Wa~ta:t'l''Stephen; grocet, f>ee'r-reiaifer Gwilliam Jn.TbreeKin~sP.ir.ChTch.ertd MittenJohn'Edward,'farmer,Ndrth end & agent for W. &i A. Gllbey, Wi~~ H-amsher John; farmer, Common farm Morgan Isa.ac, shoe m!L. St.(iabriel's ter spirit merchant's', Po~t offi~ ·•'! ':~'3 Hartland James, fll.rhler~ 'fhe Chesn.uts Osborne George, (arm~r, Btitler 1 Watkins' By. blacksmith, GiUfett's·~ Hill thomas, booi maker, Quar lane · Page William, cooper Watson c ieorge, farmer, Mereva.le Hirons Wm. farmer, 'Parsonage farm Reynolds William, Carpenter & shOJ?· Weaver Robert Reo, miller(wate~),But· Home or the ~ood Shepherd (Miss keeper, Gilbert's end ley mill • t 1 Boultbee, lady matron; Rev. George Rimel William, farmer; Herbert's farm Webb James-, carpenter, Spring 00~ Thomas Fieldwick, hon. chaplain) · Rob bins Rt.head gardnr.& land steward West William, baker & grocer, Habley J ones Henry, beer retailer & butcher, to Sir E. A. H. Lechmere hart. M. P green • 1 Hanley green' · ·• · Russell Charles, farmer, The Common Wild John, farmer, Ivy honse ' Jones Hy. -

The Eagle 1910 (Michaelmas Term)

iv CONTENTS. PAGE Notes from the College Records (collli'llued) 257 The Quatercentenary Dinners 275 The Commemoration Sermon 277 The Lady Margaret in Shakespeare 284 Gott unci Welt-Procemion 290 Reculver 291 The Viking's Wraith 292 A Serpentine Bowl 297 THE EAGLE. Marionettes 298 Ode on the Immediate Prospect of the Easter Vacation 302 October Term, I9IO. Music and the Lay Mind 303 Meleager 307 The Lights of Home 309 NOTE S FR OM THE COLLEGE REC ORDS. Obituary: Christopher John Clark 310 (Continued from Vol. XXXI., p. 316.) Philip Pennant 310 HE first gr ou p of documen ts which fo llow Sir Thomas Anclros De La Rue, Bart. 312 relate to Mr Alan Percy , second Mast er of The Rev. J. Foxley 312 the Colle ge. He is fir st met with as Pre The late Dr Foxwell-Memorial Tablet unveiled 313 bendary of Du nnin gton in York Cath edral, Completed �ist of Professor J. E. B. Mayor's Vegetarian Publications 316 to wh ich he was admitted 1 May 1513. He was Our Chronicle 318 admitted Master of St John's July 15 r6, at the fo rma 29 The Library 334 l openin g of the Colle ge, thou gh he seems to have been pe rformin g the duties fo r abo ut a month befo re that date. He vacated his Prebend at Yo rk in and Robert Shorton, his pr edecessor as Master 1.517 of St John's, succe eded him there , 1 November 15 Mr Percy had been appo inted Rector of St 17·Anne with St Agnes in the City of London by the Abbo t and Convent ofWestm inster, and was in stituted 6 May I 5 5.I He resi gned both his Rectory and his Master shi p in I,•p8 ; up to the pr esent no reason for these res ignations ha s come to li ght. -

Trinity College Library Cambridge Finding

Trinity College Library Cambridge Finding Aid - Papers of the Monk and Sanford Families (MONK) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.5.3 Printed: February 12, 2020 Language of description: English Trinity College Library Cambridge Trinity College Library Cambridge CB2 1TQ Telephone: 0044 (0)1223 338488 Email: [email protected] https://archives.trin.cam.ac.uk/index.php/papers-of-the-monk-and-sanford-families Papers of the Monk and Sanford Families Table of contents Summary information .................................................................................................................................... 34 Scope and content ......................................................................................................................................... 34 Notes .............................................................................................................................................................. 34 Bibliography .................................................................................................................................................. 35 Collection holdings ........................................................................................................................................ 35 MONK/A, Papers of James Henry Monk (1805–55) ................................................................................ 35 MONK/A/1, Personal correspondence (1808–55) ................................................................................... 35 MONK/A/1/1, Letter -

In the Lands of the Romanovs an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917)

In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross Publisher: Open Book Publishers Year of publication: 2014 Published on OpenEdition Books: 29 November 2016 Serie: OBP collection Electronic ISBN: 9782821876224 http://books.openedition.org Printed version ISBN: 9781783740574 Number of pages: xvi + 432 Electronic reference CROSS, Anthony. In the Lands of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917). New edition [online]. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2014 (generated 19 décembre 2018). Available on the Internet: <http://books.openedition.org/ obp/2350>. ISBN: 9782821876224. © Open Book Publishers, 2014 Creative Commons - Attribution 4.0 International - CC BY 4.0 ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers IN THE LANDS OF THE ROMANOVS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. -

Russell's Morayshire Register, and Elgin and Forres Directory

APSJ.2og.03s ,\/ Digitized by the Internet' Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/russellsmorayshi1852elgi :! RUSSELL'S MORAYSHIRE REGISTER, AND ELGIN AND FORRES DIRECTORY, FOE 1852, Mtins Heap fear, DEDICATED, BY SPECIAL PERMISSION, TO :&e mm Hon- Cfte ©arl of ffitt. ELGIN:; PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY ALEX. RUSSELL, CO U RANT OFFICE, AND SOLD BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. Price Is. Qd. Bound in Cloth, • . — INDEX TO THE CONTENTS. PART I.—GENERAL ALMANACK. Arehbishops of England 54 Palaces, Hereditary Keepers. ..71 Assessed Taxes 43 Parliaments, Imperial 68 Bank Holidays., 7 Peers, House of.., 53 Banks and Banking Companies 45 Peerage, Scottish ,70 Banks & Branches in Scotland 45 Peers, Scottish Representative57 Bill Card for 1852....... 50 Peers, Irish Representative 57 Bishops of England 55 Peers, Officers of the House.. ..58 British Empire, Extent and Peeresses in their own Right... 58 Population of 52 Prelates, Irish Representative.. 58 British Ministry 53 Quarters of the Year, 8 Cattle, Rule for Weighing 41 Railway Communication 73 Chronicle and Obituary, Royal Family 52 1850-51. 77 Salaries and Expenses, Table Chronological Cycles .8 for Calculating 36 Commons, House of, .....58 Savings' Bank, National Se- Commons, Officers of the curity.., 44 House of 68 Scotland, Extent, &c 44 Corn, Duties on , 40 Scotland, Judges and Officers.. 69 Distance Table of Places in Scotland, Officers of State in... 71 Elginshire 7 Scotland, Population, Lords- Eclipses of the Sun and Moon 8 Lieutenant, and Sheriffs 69 European States, Population, Scotland, Summary of the Po- and Reigning Sovereigns 52 pulation in 1821, 1831, Excise Duties ...41 1841, and 1851 70 Fairs in Scotland 21 Scotland, Universities of 71 Fairs in North of England 35 Scotland, View of the Pro- Fast Days.... -

Bishops of Worcester

Bishops of Worcester From Until Incumbent Notes 680 691 Bosel Resigned the See 691 693 Oftfor 693 717 Ecgwine of Evesham Also recorded as Ecgwin, Egwin and Eegwine 718 c744 Wilfrith Also recorded as Wilfrid c743 c775 Milred Also recorded as Mildred and Hildred 775 777 Waermund 777 c780/81 Tilhere 781 c799 Heathured Also recorded as Hathored and AEthelred c799 822 Denebeorht Also recorded as Deneberht 822 c845/48 Heahbeorht Also recorded as Heahberht and Eadbert c845/48 872 Ealhhun Also recorded as Alwin 873 915 Werferth Also recorded as Waerfrith, Waerferth, Werfrith and Waerfrith 915 922 AEthelhun 922 929 Wilfrith 929 957 Koenwald Also recorded as Cenwald and Coenwald 957 959 Dunstan Previouely Abbot of Glastonbury, Translated to London; and leter to Canterbury 961 992 Oswald Held both Worcester and York (971-992) 992 1002 Ealdwulf Previously Abbot of Peterborough; held both Worcester and York (995-1002) 1002 1016 Wulfstan Translated from London; also Archbishop of York (1002-1023) 1016 1033 Leofsige 1033 1038 Beorhtheah c1038/39 1040 Lyfing (1st term) Deprived from Worcester; also Bishop of Crediton and Cornwall (1027-1046) 1040 1041 AElfric Puttoc Also Archbishop of York 1023-1041; deprived from both 1041 1046 Lyfing (2nd term) Restored to Worcester 1046 1061 Ealdred Translated from Hereford; later to York 1062 1095 Wulfstan Canonized on 14 May 1203 by Pope Innocent III Conquest to the Reformation 1096 1112 Samson 1113 1123 Theulf Nominated in 1113; consecrated in 1115 1125 1150 Simon 1151 1157 John de Pageham 1158 1160 Alured 1163