Involving Parents As Partners for Youth Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homeschooling and the Question of Socialization Revisited

Homeschooling and the Question of Socialization Revisited Richard G. Medlin Stetson University This article reviews recent research on homeschooled children’s socialization. The research indicates that homeschooling parents expect their children to respect and get along with people of diverse backgrounds, provide their children with a variety of social opportunities outside the family, and believe their children’s social skills are at least as good as those of other children. What homeschooled children think about their own social skills is less clear. Compared to children attending conventional schools, however, research suggest that they have higher quality friendships and better relationships with their parents and other adults. They are happy, optimistic, and satisfied with their lives. Their moral reasoning is at least as advanced as that of other children, and they may be more likely to act unselfishly. As adolescents, they have a strong sense of social responsibility and exhibit less emotional turmoil and problem behaviors than their peers. Those who go on to college are socially involved and open to new experiences. Adults who were homeschooled as children are civically engaged and functioning competently in every way measured so far. An alarmist view of homeschooling, therefore, is not supported by empirical research. It is suggested that future studies focus not on outcomes of socialization but on the process itself. Homeschooling, once considered a fringe movement, is now widely seen as “an acceptable alternative to conventional schooling” (Stevens, 2003, p. 90). This “normalization of homeschooling” (Stevens, 2003, p. 90) has prompted scholars to announce: “Homeschooling goes mainstream” (Gaither, 2009, p. 11) and “Homeschooling comes of age” (Lines, 2000, p. -

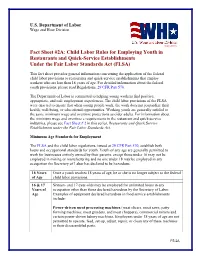

Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division (July 2010) Fact Sheet #2A: Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) This fact sheet provides general information concerning the application of the federal child labor provisions to restaurants and quick-service establishments that employ workers who are less than 18 years of age. For detailed information about the federal youth provisions, please read Regulations, 29 CFR Part 570. The Department of Labor is committed to helping young workers find positive, appropriate, and safe employment experiences. The child labor provisions of the FLSA were enacted to ensure that when young people work, the work does not jeopardize their health, well-being, or educational opportunities. Working youth are generally entitled to the same minimum wage and overtime protections as older adults. For information about the minimum wage and overtime e requirements in the restaurant and quick-service industries, please see Fact Sheet # 2 in this series, Restaurants and Quick Service Establishment under the Fair Labor Standards Act. Minimum Age Standards for Employment The FLSA and the child labor regulations, issued at 29 CFR Part 570, establish both hours and occupational standards for youth. Youth of any age are generally permitted to work for businesses entirely owned by their parents, except those under 16 may not be employed in mining or manufacturing and no one under 18 may be employed in any occupation the Secretary of Labor has declared to be hazardous. 18 Years Once a youth reaches 18 years of age, he or she is no longer subject to the federal of Age child labor provisions. -

Youth Participation in Electoral Processes Handbook for Electoral Management Bodies

Youth Participation in Electoral Processes Handbook for Electoral Management Bodies FIRST EDITION: March 2017 With support of: European Commission United Nations Development Programme Global Project Joint Task Force on Electoral Assistance for Electoral Cycle Support II ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Lead authors Ruth Beeckmans Manuela Matzinger Co-autors/editors Gianpiero Catozzi Blandine Cupidon Dan Malinovich Comments and feedback Mais Al-Atiat Julie Ballington Maurizio Cacucci Hanna Cody Kundan Das Shrestha Andrés Del Castillo Aleida Ferreyra Simon Alexis Finley Beniam Gebrezghi Najia Hashemee Regev Ben Jacob Fernanda Lopes Abreu Niall McCann Rose Lynn Mutayiza Chris Murgatroyd Noëlla Richard Hugo Salamanca Kacic Jana Schuhmann Dieudonne Tshiyoyo Rana Taher Njoya Tikum Sébastien Vauzelle Mohammed Yahya Lea ZoriĆ Copyeditor Jeff Hoover Graphic desiger Adelaida Contreras Solis Disclaimer This publication is made possible thanks to the support of the UNDP Nepal Electoral Support Project (ESP), generously funded by the European Union, Norway, the United Kingdom and Denmark. The information and views set out in this publication are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the UN or any of the donors. The recommendations expressed do not necessarily represent an official UN policy on electoral or other matters as outlined in the UN Policy Directives or any other documents. Decision to adopt any recommendations and/or suggestions presented in this publication are a sovereign matter for individual states. Youth -

Youth Voter Participation

Youth Voter Participation Youth Voter Participation Involving Today’s Young in Tomorrow’s Democracy Copyright © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) 1999 All rights reserved. Applications for permission to reproduce all or any part of this publication should be made to: Publications Officer, International IDEA, S-103 34 Stockholm, Sweden. International IDEA encourages dissemination of its work and will respond promptly to requests for permission for reproduction or translation. This is an International IDEA publication. International IDEA’s publications are not a reflection of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA’s Board or Council members. Art Direction and Design: Eduard âehovin, Slovenia Illustration: Ana Ko‰ir Pre-press: Studio Signum, Slovenia Printed and bound by: Bröderna Carlssons Boktryckeri AB, Varberg ISBN: 91-89098-31-5 Table of Contents FOREWORD 7 OVERVIEW 9 Structure of the Report 9 Definition of “Youth” 9 Acknowledgements 10 Part I WHY YOUNG PEOPLE SHOULD VOTE 11 A. Electoral Abstention as a Problem of Democracy 13 B. Why Participation of Young People is Important 13 Part II ASSESSING AND ANALYSING YOUTH TURNOUT 15 A. Measuring Turnout 17 1. Official Registers 17 2. Surveys 18 B. Youth Turnout in National Parliamentary Elections 21 1. Data Sources 21 2. The Relationship Between Age and Turnout 24 3. Cross-National Differences in Youth Turnout 27 4. Comparing First-Time and More Experienced Young Voters 28 5. Factors that May Increase Turnout 30 C. Reasons for Low Turnout and Non-Voting 31 1. Macro-Level Factors 31 2. -

Reconsidering the Minimum Voting Age in the United States

Reconsidering the Minimum Voting Age in the United States Benjamin Oosterhoff1, Laura Wray-Lake2, & Daneil Hart3 1 Montana State University 2 University of California, Los Angeles 3 Rutgers University Several US states have proposed bills to lower the minimum local and national voting age to 16 years. Legislators and the public often reference political philosophy, attitudes about the capabilities of teenagers, or past precedent as evidence to support or oppose changing the voting age. Dissenters to changing the voting age are primarily concerned with whether 16 and 17-year-olds have sufficient political maturity to vote, including adequate political knowledge, cognitive capacity, independence, interest, and life experience. We review past research that suggests 16 and 17-year-olds possess the political maturity to vote. Concerns about youths’ ability to vote are generally not supported by developmental science, suggesting that negative stereotypes about teenagers may be a large barrier to changing the voting age. Keywords: voting, adolescence, rights and responsibility, politics Voting represents both a right and responsibility within tory and rooted in prejudiced views of particular groups’ ca- democratic political systems. At its simplest level, voting is pabilities. Non-white citizens were not granted the right to an expression of a preference (Achen & Bartels, 2017) in- vote until the 1870s, and after being legally enfranchised, tended to advance the interests of oneself or others. Voting literacy tests were designed to prevent people of color from is also a way that one of the core qualities of citizenship— voting (Anderson, 2018). The year 2020 marks the 100th participation in the rule-making of a society—is exercised. -

Adjusting the Bright-Line Age of Accountability Within the Criminal

Duquesne Law Review Volume 55 Number 1 Drafting Statutes and Rules: Article 8 Pedagogy, Practice, and Politics 2017 Adjusting the Bright-Line Age of Accountability within the Criminal Justice System: Raising the Age of Majority to Age 21 Based on the Conclusions of Scientific Studies egarr ding Neurological Development and Culpability of Young-Adult Offenders Carly Loomis-Gustafson Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr Part of the Juvenile Law Commons Recommended Citation Carly Loomis-Gustafson, Adjusting the Bright-Line Age of Accountability within the Criminal Justice System: Raising the Age of Majority to Age 21 Based on the Conclusions of Scientific Studies egarr ding Neurological Development and Culpability of Young-Adult Offenders, 55 Duq. L. Rev. 221 (2017). Available at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr/vol55/iss1/8 This Student Article is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Duquesne Law Review by an authorized editor of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. Adjusting the Bright-Line Age of Accountability within the Criminal Justice System: Raising the Age of Majority to Age 21 based on the Conclusions of Scientific Studies Regarding Neurological Development and Culpability of Young-Adult Offenders Carly Loom is-Gustafson* ABSTRACT The criminaljustice system determines a criminalactor's liability based primarily on the age of the actor at the time of the offense, adhering to a rule instituted by arbitrary designationof adulthood at the age of eighteen. Solely, this line determines the degree of treat- ment a criminal defendant will receive within the system, with more punitive measures being reserved for adult offenders and greater re- habilitative efforts made for juvenile offenders. -

Child Marriage and POVERTY

Child Marriage and POVERTY Child marriage is most common in the world’s poorest countries and is often concentrated among the poorest households within those countries. It is closely linked with poverty and low levels of economic development. In families with limited resources, child marriage is often seen as a way to provide for their daughter’s future. But girls who marry young are IFAD / Anwar Hossein more likely to be poor and remain poor. CHILD MARRIAGE Is INTIMATELY shows that household economic status is a key factor in CONNEctED to PovERTY determining the timing of marriage for girls (along with edu- cation and urban-rural residence, with rural girls more likely Child marriage is highly prevalent in sub- to marry young). In fact, girls living in poor households are Saharan Africa and parts of South Asia, the approximately twice as likely to marry before 18 than girls two most impoverished regions of the world.1 living in better-off households.4 • More than half of the girls in Bangladesh, Mali, Mozam- In Côte d’Ivoire, a target country for the President’s Emer- bique and Niger are married before age 18. In these same gency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), girls in the poorest countries, more than 75 percent of people live on less than $2 a day. In Child Marriage in the Poorest and Richest Households Mali, 91 percent of the in Select Countries population lives on less 80 than $2 a day. 2 70 • Countries with low GDPs tend to have a higher 60 prevalence of child mar- riage. -

Youth Governance: Strengthening and Maintaining Youth Committees to Improve Services for Youth

Youth Governance: Strengthening and Maintaining Youth Committees to Improve Services for Youth STATE PLAN LOCAL PLAN POLICIES & GUIDANCE BUDGET CHOICES CLASP's Opportunities for Action is a series of short memos with recommendations for state and local areas to fully realize the options in the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) to help low-income and lower-skilled youth and adults achieve economic success. WIOA title I youth requires that at least 75 percent of available state-wide funds and 75 percent of funds available to local areas be spent on workforce investment services for out-of-school youth. This is an increase from 30 percent under the Workforce Investment Act (WIA). In addition, WIOA raises the eligibility range for out-of-school youth from 16-21 to 16-24. This redirected funding gives states and local communities dedicated resources to implement effective employment, education, and youth development strategies for the most vulnerable young people in highly distressed communities. Similarly, raising the eligibility age could help states and local areas better target their programming for this population of youth who are transitioning into adulthood. There is no one system that serves out-of-school youth, and out-of-school youth are more likely to touch multiple systems. Consequently, specific developmental needs often go unmet, especially among youth served through the adult workforce system. Unlike WIA, WIOA does not require local workforce boards to maintain youth councils. However, WIOA does allow local boards to establish standing youth committees, as well as continue any existing youth councils established under the previous law. -

Prepare Your Child for Age of Majority and Transfer of Rights*

INSPIRING POSSIBILITIES Prepare Your Child for Age of Majority and Transfer of Rights* Parents want their children to have the skills they need to a statement that the student has been informed of his or succeed as adults. While this is important for every young her rights and responsibilities under IDEA. person, youth with disabilities often face extra challenges. • The public agency (the school) will provide required That’s why they need to be actively involved in setting notices to both the student and the parents. This their high school goals and planning for their transition to regulation does not apply to students who have been adulthood well before they reach the age of majority. Age of determined to be “incompetent” under state law. majority is the legal age established under state law at which Rights that Transfer an individual is no longer a minor and, as a young adult, has the right and responsibility to make certain legal choices In states that transfer educational rights at the age of majority, that adults make. This is called transfer of rights. In most all of the educational rights provided to the parents transfer states, the age of majority is 18, but there are exceptions. It is to the student when he or she reaches the age of majority. important to know your state’s laws. These educational rights may include the rights to: Takeaways from this handout: • receive notice of and attend Individualized Education Program (IEP) meetings • Most young adults, usually at age 18, are granted certain • consent to reevaluation legal rights including special education rights. -

Unit on ADULTISM

http://www.socialjusticeeducation.org Tools for Building Justice, January, 2003 Unit On ADULTISM Unit Outline Session # 1. Introduction Introducing the concept of unequal treatment for youth and adults, the session explores stereotypes and putdowns of young people and analyzes two scenes of youth/adult interaction. 2. Adultism This session focuses on adultism and internalized adultism: how young people are mistreated or discriminated against in adult-defined institutions and how young people can internalize mistreatment against themselves and other youth. Session closes with strengths of young people. 3. Adults This session examines the conditioning process of becoming an adult, identifying the costs and privileges of adulthood and the requirements for being an adult ally to youth. 4. Organizing/Action Unit on Adultism 1 SESSION 1. Introduction Aims • To introduce the unit on adultism • To identify and discuss two day-to-day conflicts between youth and adults Skills Students will: • Identify negative stereotypes applied to young people as a group • Identify target and nontarget group members in two conflicts affecting youth and adults • Apply the concept of unequal treatment of youth and adults to other youth/adult relationships besides those depicted Preparation Consult with appropriate school counseling personnel ahead of time about the unit, lining up adults for young people to talk to. Make sure you have reviewed local guidelines for mandated reporting of child abuse, and prepare a simple, clear statement to make to students. You will need photos and 2 pieces of butcher paper and markers for the adult/youth brainstorm. Note that there is one photo with uncaptioned and captioned versions: prepare the discussion accordingly. -

Research Facts on Homeschooling

RESEARCH FACTS ON HOMESCHOOLING Brian D. Ray, Ph.D. January 6, 2015 General Facts and Trends • Homeschooling – that is, parent-led home-based education – is an age-old traditional educational practice that a decade ago appeared to be cutting-edge and “alternative” but is now bordering on “mainstream” in the United States. It may be the fastest-growing form of education in the United States. Home-based education has also been growing around the world in many other nations (e.g., Australia, Canada, France, Hungary, Japan, Kenya, Russia, Mexico, South Korea, Thailand, and the United Kingdom). • There are about 2.2 million home-educated students in the United States. There were an estimated 1.73 to 2.35 million children (in grades K to 12) home educated during the spring of 2010 in the United States (Ray, 2011). It appears the homeschool population is continuing to grow (at an estimated 2% to 8% per annum over the past few years). • Families engaged in home-based education are not dependent on public, tax-funded resources for their children’s education. The finances associated with their homeschooling likely represent over $24 billion that American taxpayers do not have to spend, annually, since these children are not in public schools • Homeschooling is quickly growing in popularity among minorities. About 15% of homeschool families are non-white/nonHispanic (i.e., not white/Anglo). • A demographically wide variety of people homeschool – these are atheists, Christians, and Mormons; conservatives, libertarians, and liberals; low-, middle-, and high-income families; black, Hispanic, and white; parents with Ph.D.s, GEDs, and no high-school diplomas. -

Homeschool Education Guide a Supplement to the Educator Guide Federal Junior Duck Stamp Program Connecting Youth with Nature Through Science and Art!

Homeschool Education Guide A Supplement to the Educator Guide Federal Junior Duck Stamp Program Connecting Youth with Nature Through Science and Art! An opportunity to investigate what is fun, unique, and mysterious about waterfowl and wetlands in North America and in your community. The mission of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is working with others to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, plants, and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people. Contents Getting Started .................................................................................................................7 What is the Junior Duck Stamp Program? ....................................................................7 Curriculum Guides and the Junior Duck Stamp Art Contest .........................................8 Junior Duck Stamp Youth Guide .............................................................................8 Junior Duck Stamp Educator Guide ........................................................................8 Junior Duck Stamp Art Contest ...............................................................................8 How is the Homeschool Guide Organized .......................................................................9 Using the Homeschool Guide ........................................................................................ 10 Learning and the Junior Duck Stamp Homeschool Guide ......................................... 10 Why Waterfowl and Wetlands for Homeschoolers? ...................................................