SEABISCUIT: a Lesson in Fixing Each Other Rosh Hashanah Morning 5764

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MJC Media Guide

2021 MEDIA GUIDE 2021 PIMLICO/LAUREL MEDIA GUIDE Table of Contents Staff Directory & Bios . 2-4 Maryland Jockey Club History . 5-22 2020 In Review . 23-27 Trainers . 28-54 Jockeys . 55-74 Graded Stakes Races . 75-92 Maryland Million . 91-92 Credits Racing Dates Editor LAUREL PARK . January 1 - March 21 David Joseph LAUREL PARK . April 8 - May 2 Phil Janack PIMLICO . May 6 - May 31 LAUREL PARK . .. June 4 - August 22 Contributors Clayton Beck LAUREL PARK . .. September 10 - December 31 Photographs Jim McCue Special Events Jim Duley BLACK-EYED SUSAN DAY . Friday, May 14, 2021 Matt Ryb PREAKNESS DAY . Saturday, May 15, 2021 (Cover photo) MARYLAND MILLION DAY . Saturday, October 23, 2021 Racing dates are subject to change . Media Relations Contacts 301-725-0400 Statistics and charts provided by Equibase and The Daily David Joseph, x5461 Racing Form . Copyright © 2017 Vice President of Communications/Media reproduced with permission of copyright owners . Dave Rodman, Track Announcer x5530 Keith Feustle, Handicapper x5541 Jim McCue, Track Photographer x5529 Mission Statement The Maryland Jockey Club is dedicated to presenting the great sport of Thoroughbred racing as the centerpiece of a high-quality entertainment experience providing fun and excitement in an inviting and friendly atmosphere for people of all ages . 1 THE MARYLAND JOCKEY CLUB Laurel Racing Assoc. Inc. • P.O. Box 130 •Laurel, Maryland 20725 301-725-0400 • www.laurelpark.com EXECUTIVE OFFICIALS STATE OF MARYLAND Sal Sinatra President and General Manager Lawrence J. Hogan, Jr., Governor Douglas J. Illig Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Tim Luzius Senior Vice President and Assistant General Manager Boyd K. -

A Film Analysis: Seabiscuit: an American Legend

Suzanne Gehring Film and Culture 1010 Marty Nabham November 24, 2008 A Film Analysis: Seabiscuit: An American Legend “If your dream was big enough and you had the guts to follow it, there was truly a fortune to be made.” - David McCullough Through literal and symbolic representation, the film Seabiscuit portrays an ongoing theme of hope in times of struggle. The movie is time-specific to the Great Depression and is a story of a few broken-down people and an equally broken-down horse who join forces in order to overcome the odds with hope. On a wider scope, such hope is symbolic of a hope that Americans searched for in order to survive during a pivotal time of devastation. The film uniquely represents the events of the era through a documentary style which consistently is in direct correlation with the main storyline throughout the movie. Specific examples of devastation on a smaller scope in the film include Charles Howard‟s (played by Jeff Bridges) loss of family through the death of his son; Red Pollard‟s (played by Tobey Maguire) suggested abandonment by his family and, later, his injury while riding; Seabiscuit‟s injury while racing, all of which are representations of overcoming the odds through hope as each of these situations are resolved. Throughout each situation, the existence of hope is suggested through the unlikely relationships between each of these characters. Specifically, the character of Tom Smith (played by Chris Cooper) is suggested to be the „glue‟ which holds each of these relationships together, as he is, in a way, the person to form each relationship. -

Seabiscuit Transcript

Seabiscuit Transcript Video transcript for SHARE. Seabiscuit This training is Identifying Symptoms: The Seabiscuit Case Study We’re about to watch a segment out of Seabiscuit and what we're going to do is we are going to treat this segment as a case study. So your job is to identify the person who has had a traumatic event and then also look at what symptoms they may have experienced and what were the reactions of the people around them. Seabiscuit dialog The first time he saw Seabiscuit, the colt was walking through the fog at five in the morning. Smith would say later that the horse looked right through him, as if to say “What the hell are you looking at? Who do you think you are?” He was a small horse, barely 15 hands. He was hurting too. There was a limp in his walk, a wheezing when he breathed. Smith didn’t pay attention to that. He was looking the horse in the eye. He was the son of Hardtack sired by the mighty Man-of-War, but the breeding did little to impress anyone at Claiborne Farm. “Get rid of him.” At six months he was shipped off the same as the legendary trainer of Sonny Fitzsimmons who, overtime, developed a similar opinion of him. “Is that a race horse or a lead pony?” The judgment wasn’t helped by his gentle nature. Where his sire had been a fierce almost violent competitor, Seabiscuit took to sleeping for huge chunks of the day, enjoyed lolling for hours under the bows of the Juniper trees. -

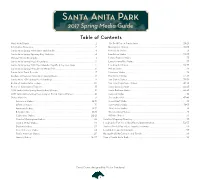

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

KPOST J FIR. T

..... __ E AND VESPER SERVICE TO FEATURE WEEK-END OF MEMORIAL EVENTS THENE KPOST j FIR. T . ---A. AY Son And Daughter Of Class Of 1914 ANNUAL TO MAY MART ~lt~r~~N Local Organizations JUNE SATURDAY NTlI IS NAMED Sponsor Ceremonies Plans Now About McClintock Aids ~ e r s In COlllpleted For Drive For Funds; Active In 1\le1110rial Day Services Annu al Benefit Affair COtnlllittee :Meets I__ -======== =- CAPTAIN IS 011 ; College With all committee membcrs Williom K. Gillespie, principal I-IEAD OF working overtime and plans about of Newark High School. director of I To Groups fini shed for the affair, the fifth an- Athletics, football, basketball and nual May Mart, scheduled to start track coach at the institution; on Saturday at one o'clock on thc Ralph O'Conncll, instructor of MEMORIAL Newark High School athletic Held, physical education and baseball is expected to prove more successful coach at the same school, and Mi ss than in U, e past, Mrs. Leon H. Ryan, J anc J ernee, completing her junior COMMITTEE general chairman, announced yes- I ycnr at the Women's Collcge of terday. Dclawarc, werc named to the sta fT Soldiers, Civic. Sponsored by the Newark P arent- of thc new community playground Tcacher Association, proceeds from and swimming pool by the general And Fraternal Pictured abovc are Arthur C. Huston, Jr., son of Mr. and Mrs. Arthur the fete, which was started Hve c o mmilt~e last week. Huston. W. Park Place, and Mi ss Janet Grubb, daughter of MI'. and Mrs. years ago, will be used for school MI'. -

Seabiscuit a Webquest for 9Th Grade English

Seabiscuit A WebQuest for 9th Grade English Designed by Susan Richardson, Media Specialist [email protected] Norman Newburn, English Teacher [email protected] Introduction | Task | Process | Evaluation | Conclusion | Credits Introduction What in the world has happened? You went to bed after reading the biography from your Holt McDougal online textbook (page 126) about Seabiscuit’s success as a race horse in the 1930’s, and then you woke up outside of a horse stable where he’s being prepped for his next big race. You are penniless, jobless, and homeless. You try to not draw any attention to yourself while you attempt to figure out what is going on and how you will get back home to your current time period. You start seeing herds of people moving towards a stadium in the distance. People are dressed “to the nines” and the sounds of announcers screeching on the speakers drift to where you are. There seems to be an event going on. You figure you might be able to get some information from someone there. As you approach the gates, you realize that this is a horse race track. How will you get inside? Luckily for you, someone walking by thinks you’re a graphic artist for a major magazine that he met at a party and wants you to cover Seabiscuit’s next race and the influence of the Great Depression on the 1930’s. The only problem: You have no idea what the 1930’s are like, much less how to design a graphic about the Great Depression. -

RICE's DERBY CHOICE JOURNAL 2012 33St Edition

RICE’S DERBY CHOICE JOURNAL 2012 33st Edition “Now there is a languor … I am fulfilled and weary. This Kentucky Derby, whatever it is — a race, an emotion, a turbulence, an explosion–is one of the most beautiful and violent and satisfying things I have ever experienced. And, I suspect that, as with other wonders, the people one by one have taken from it exactly as much good or evil as they brought to it… I am glad I have seen and felt it at last.” ‐John Steinbeck (1956) Copyright © 2012 Tim Rice All Rights Reserved 1 I think you will soon agree with me that there is a great deal more annoyance and vexation in race horses than real pleasure.” - August Belmont writing to his son August Belmont, Jr. Rare was the voting-age American ignorant of that colossus, Secretariat, and his supra- equine achievement in the third leg of the 1973 Triple Crown. That thirty-one length score, in still world record time for a mile and a half, completed the colt’s sweep of the three-year-old classic fixtures. He was acclaimed from sea to shining sea including the covers of Time, Newsweek, and Sports Illustrated. And, no small task that because 1973 was not without many headline grabbers including the Watergate Hearings and the departure of the last U.S. soldier from Viet Nam. Of lesser note were the declaration of Ferdinand Marcos as President for Life of the Philippines, the sale of the New York Yankees to George Steinbrenner for ten million dollars, and O.J. -

1930S Greats Horses/Jockeys

1930s Greats Horses/Jockeys Year Horse Gender Age Year Jockeys Rating Year Jockeys Rating 1933 Cavalcade Colt 2 1933 Arcaro, E. 1 1939 Adams, J. 2 1933 Bazaar Filly 2 1933 Bellizzi, D. 1 1939 Arcaro, E. 2 1933 Mata Hari Filly 2 1933 Coucci, S. 1 1939 Dupuy, H. 1 1933 Brokers Tip Colt 3 1933 Fisher, H. 0 1939 Fallon, L. 0 1933 Head Play Colt 3 1933 Gilbert, J. 2 1939 James, B. 3 1933 War Glory Colt 3 1933 Horvath, K. 0 1939 Longden, J. 3 1933 Barn Swallow Filly 3 1933 Humphries, L. 1 1939 Meade, D. 3 1933 Gallant Sir Colt 4 1933 Jones, R. 2 1939 Neves, R. 1 1933 Equipoise Horse 5 1933 Longden, J. 1 1939 Peters, M. 1 1933 Tambour Mare 5 1933 Meade, D. 1 1939 Richards, H. 1 1934 Balladier Colt 2 1933 Mills, H. 1 1939 Robertson, A. 1 1934 Chance Sun Colt 2 1933 Pollard, J. 1 1939 Ryan, P. 1 1934 Nellie Flag Filly 2 1933 Porter, E. 2 1939 Seabo, G. 1 1934 Cavalcade Colt 3 1933 Robertson, A. 1 1939 Smith, F. A. 2 1934 Discovery Colt 3 1933 Saunders, W. 1 1939 Smith, G. 1 1934 Bazaar Filly 3 1933 Simmons, H. 1 1939 Stout, J. 1 1934 Mata Hari Filly 3 1933 Smith, J. 1 1939 Taylor, W. L. 1 1934 Advising Anna Filly 4 1933 Westrope, J. 4 1939 Wall, N. 1 1934 Faireno Horse 5 1933 Woolf, G. 1 1939 Westrope, J. 1 1934 Equipoise Horse 6 1933 Workman, R. -

2018 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 FIRST RUNNING the First Running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park Took Place on a Thursday

2018 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 FIRST RUNNING The first running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park took place on a Thursday. The race was 1 5/8 miles long and the conditions included “$200 each; half forfeit, and $1,500-added. The second to receive $300, and an English racing saddle, made by Merry, of St. James TABLE OF Street, London, to be presented by Mr. Duncan.” OLDEST TRIPLE CROWN EVENT CONTENTS The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is the oldest of the Triple Crown events. It predates the Preakness Stakes (first run in 1873) by six years and the Kentucky Derby (first run in 1875) by eight. Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ran second in the 1875 Belmont behind winner Calvin. RECORDS AND TRADITIONS . 4 Preakness-Belmont Double . 9 FOURTH OLDEST IN NORTH AMERICA Oldest Triple Crown Race and Other Historical Events. 4 Belmont Stakes Tripped Up 19 Who Tried for Triple Crown . 9 The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is one of the oldest stakes races in North America. The Phoenix Stakes at Keeneland was Lowest/Highest Purses . .4 How Kentucky Derby/Preakness Winners Ran in the Belmont. .10 first run in 1831, the Queens Plate in Canada had its inaugural in 1860, and the Travers started at Saratoga in 1864. However, the Belmont, Smallest Winning Margins . 5 RUNNERS . .11 which will be run for the 150th time in 2018, is third to the Phoenix (166th running in 2018) and Queen’s Plate (159th running in 2018) in Largest Winning Margins . -

Meghan Mccarthy

Launching Nonfiction Author Studies: A focus for teaching the Common Core State Standards with books by MEGHAN MCCARTHY Books Daredevil: The Wildest Race Ever: Pop!: The Daring Life of The Story of the 1904 The Invention of Betty Skelton Olympic Marathon Bubble Gum Seabiscuit Earmuffs for Everyone!: City Hawk: the Wonder Horse How Chester Greenwood Became The Story of Pale Male Known as the Inventor of Earmuffs Background Information Introduce younger readers to picture book biographies of daring and inventive people such as “daredevil” Betty Skelton—who broke speed records on the ground, in the air, and in the water—and Walter Diemer, the accoun- tant-turned-experimental-scientist who invented bubble gum. Learn about animals that people have taken to their hearts, such as Pale Male, the red-tailed hawk that built a nest on the side of an apartment building overlooking New York City’s Central Park, and Seabiscuit, the horse who went from being an underdog to being a champion racehorse. Each story is complemented by Meghan McCarthy’s bold, acrylic paintings featuring her trademark “googly-eyed” portraits. These biographies are perfect for supporting content area learning and for introducing the features of biography. Encourage students to discuss the content of these books and share their ideas in writing. Nonfiction Author Study Sets / Meghan McCarthy 1 Activities for Launching Your Author Study CCSS Connection: The first two activities below deal with asking and answering questions about a text, identifying the main topic and key details that support it, and describing the relationship between a series of events, concepts, or ideas (RI.1–2.1) (RI.1–3.2). -

Haras La Pasioì N

ÍNDICE ESTADÍSTICAS ESTADÍSTICAS GENERALES ESTADÍSTICAS BLACK TYPE DESTACADOS 2016 GANADORES CLÁSICOS REFERENCIA DE PADRILLOS EASING ALONG MANIPULATOR ZENSATIONAL SIDNEY’S CANDY SIXTIES ICON VIOLENCE LIZARD ISLAND NOT FOR SALE EMPEROR RICHARD ROMAN RULER KEY DEPUTY POTRILLOS 1 Liso Y Llano Easing Along - Potra Liss por Potrillon 2 Giradisco Easing Along - Gincana por Lode 3 Portofinense Easing Along - Prolongada por Tiznow 4 Mikonos Grand Easing Along - Magic Sale por Not For Sale 5 Infobae Easing Along - Idyllic por Halo Sunshine 6 Anime Easing Along - Abide por Pivotal 7 Vuemont Easing Along - Valentini por Boston Harbor 8 Gingerland Easing Along - Gone For Christmas por Gone West 9 Illegallo Easing Along - Illegally Blonde por Southern Halo ÍNDICE 10 Santinesi Easing Along - Santita por Maria’s Mon 11 Buen Gusto BO Easing Along - Buena Alegria por Interprete 12 Falabello Not For Sale - Fancy Tale por Rahy 13 Fashion Kid Not For Sale - Fashion Model por Rainbow Quest 14 Grecko Not For Sale - Grecian por Equalize 15 EL Viruta Not For Sale - La Impaciente por Bernstein 16 Scandalous Not For Sale - Sa Torreta por Southern Halo 17 American Tattoo Not For Sale - American Whisper por Quiet American 18 Paco Meralgo Not For Sale - Potential Filly por Thunder Gulch 19 Palpito Fuerte Not For Sale - Palpitacion por Thunder Gulch 20 Sale Tinder Not For Sale - Smashing Glory por Honour And Glory 21 Onagro Not For Sale - Orientada por Grand Slam 22 Emotividad Not For Sale - Embrida por Lizard Island 23 Verso DE Amor Not For Sale - Stormy Venturada -

Alhambra and the Kentucky Derby

Alhambra and the Kentucky Derby By Gary Frueholz, Dilbeck Real Estate A winner of the Kentucky Derby used to call Alhambra home... and I am not speaking about a person. Determine won the 1954 Kentucky Derby. Out of the mold of Seabiscuit, the legendary winner of the 1939 Santa Anita Handicap, Determine was a small horse with a determined nature. In the Kentucky Derby that year, Determine was the smallest of the 17 entries. But unlike Seabiscuit, a horse with an unorthodox gate that people joked about looking more appropriate pulling a milk truck, Determine, with his picturesque proportions and classic stride gave the clear message of being a racehorse. Alhambra notable, Andy Crevolin, not only owned the Chrysler dealership at Main Street and Bushnell Street in our city during the 1930's through 1950's, but also established one of horse racing's most impressive stables of thoroughbreds during the 1940's and 50's. His star horse was Determine. And Andy Crevolin kept his stable here in Alhambra, south of Poplar Boulevard between Main Street and Fremont Avenue at the bottom of the hill, where the Target Department Store now is. Gary Wagner and his brother grew up in Alhambra near the Crevolin stables during the 1940's and 50's. Gary's brother Ron, exercised Crevolin's horses, and this afforded Gary with a good perspective of the race horses. "My brother would exercise the horses," said Gary Wagner. "He (Crevolin) had Determine at the Popular stables." By mid 1950's a higher and better use of the land the Crevolin stables occupied had been found and the stable was closed with many of the horses then being moved out to Santa Anita.