Thinking in Babel 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELI STUDENT VOICES Volume 15, Issue 3 Fall, 2011

ELI STUDENT VOICES Volume 15, Issue 3 Fall, 2011 Happily Never After… (1st Place) and her parents stayed together the last time. Mariah's parents wanted to run away, but she did not want to see them beaten by Lan Phung the henchmen of the squire. She said to them: “No father, R/W 43 mother. Necessity knows no laws. This is my choice, I reap as I sow.” A long time ago, there was a beautiful girl named “We do not want to lose you forever. Blood is thicker “Mariah”. Mariah has a pure beauty like an wonderful smelling than water. You are our only daughter. How can we live without flower that can make any man's heart go round and round just you?” Mariah's parents said. concentrically. She has curly golden hair, azure eyes, coral lips “So much to do, so much has been done. We have no and a dimple on her face. She has soft skin like a baby and choice. Please do not worry for me. I will be happy.” Mariah always is odoriferous. Mariah not only has these about her. told them. Mariah's silky words and her beautiful smile are like aqua fresh They stayed together to enjoy their last time before she air and could make anyone's day. She was the only daughter of left. her parents. They live on a small farm with a happy life. The next day, the henchmen came to pick her up by But a happy life was not enough to live. They were just carriage. -

PRI Chalice Lessons-All Units

EPISCOPAL CHILDREN’S CURRICULUM PRIMARY CHALICE Chalice Year Primary Copyright © 2009 Virginia Theological Seminary i Locke E. Bowman, Jr., Editor-in-Chief Amelia J. Gearey Dyer, Ph.D., Associate Editor The Rev. George G. Kroupa III, Associate Editor Judith W. Seaver, Ph.D., Managing Editor (1990-1996) Dorothy S. Linthicum, Managing Editor (current) Consultants for the Chalice Year, Primary Charlie Davey, Norfolk, VA Barbara M. Flint, Ruxton, MD Martha M. Jones, Chesapeake, VA Burleigh T. Seaver, Washington, DC Christine Nielsen, Washington, DC Chalice Year Primary Copyright © 2009 Virginia Theological Seminary ii Primary Chalice Contents BACKGROUND FOR TEACHERS The Teaching Ministry in Episcopal Churches..................................................................... 1 Understanding Primary-Age Learners .................................................................................. 8 Planning Strategies.............................................................................................................. 15 Session Categories: Activities and Resources ................................................................... 21 UNIT I. JUDGES/KINGS Letter to Parents................................................................................................................... I-1 Session 1: Joshua................................................................................................................. I-3 Session 2: Deborah............................................................................................................. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Disclosure Guide

2010 - 2011 Disclosure Guide RCI® Weeks This publication contains information that indicates resorts participating in, and explains the terms, conditions and use of the RCI Weeks Exchange Program operated by RCI, LLC. You are urged to read it carefully. DISCLOSURE GUIDE TO THE RCI WEEKS Kirsten Hotchkiss EXCHANGE PROGRAM Senior Vice President, Legal and Assistant Secretary 22 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 This Disclosure Guide explains the RCI Weeks Exchange Program offered to Vacation Owners by RCI, Susan Loring Crane LLC (“RCI”). Vacation Owners should carefully review Group Vice President, Legal and Assistant Secretary this information to ensure full understanding of the 22 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 terms, conditions, operation and use of the RCI Weeks Exchange Program. Note: Unless otherwise stated Nicola Rossi herein, capitalized terms in this document have the Senior Vice President same meaning as those in the Terms and Conditions of 22 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 RCI Weeks Subscribing Membership, which are also included in this document. Steve Meetre Vice President, Legal and Assistant Secretary RCI is the operator of the RCI Weeks Exchange 22 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 Program. No government agency has approved the merits of this exchange program. Lynn A. Feldman Senior Vice President and Secretary RCI is a Delaware limited liability company with its 22 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 principal office located at: Gregory T. Geppel 7 Sylvan Way Vice President, Tax Parsippany, NJ 07054 22 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 Exchanges through the RCI Weeks Exchange Program Gail Mandel are processed at: Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer 7 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 9998 North Michigan Road Carmel, IN 46032 Barry Goldschmidt Vice President and Assistant Treasurer RCI is a subsidiary of Wyndham Worldwide Corporation, 7 Sylvan Way, Parsippany, NJ 07054 a Delaware corporation. -

Eça De Queirós

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Apollo !1 Naturalism Against Nature: Kinship and Degeneracy in Fin-de-siècle Portugal and Brazil David James Bailey" Trinity Hall 1/9/17 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy !2 DECLARATION This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit. !3 Abstract The present thesis analyses the work of four Lusophone Naturalist writers, two from Portugal (Abel Botelho and Eça de Queirós) and two from Brazil (Aluísio Azevedo and Adolfo Caminha) to argue that the pseudoscientific discourses of Naturalism, positivism and degeneration theory were adapted on the periphery of the Western world to critique the socio-economic order that produced that periphery. A central claim is that the authors in question disrupt the structure of the patriarchal family — characterised by exogamy and normative heterosexuality — to foster alternative notions of kinship that problematise the hegemonic mode of transmitting name, capital, bloodline and authority from father to son. -

Asia & Australia Study for Grades

Missions Alive! Asia & Australia Study for Grades 1-6 Australia, Cambodia, Creative Access, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, the Philippines, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam Free Methodist World Missions Fall 2010 - Spring 2011 page 1 Missions Alive! 2010-2011 How to use Missions Alive! Put this curriculum in a three-ring binder for easy use. In order to fi nd the sections quickly, you might want to make index tabs to separate them. A sticky note on the fi rst page of each sec- tion might even do the trick. Feel free to make as many copies of the curriculum as you need for each teacher and student. You may also download the curriculum from our Web site, www.fmwm.org. We hope you fi nd this curriculum user-friendly. Drop us a line and let us know what you think about Missions Alive! - Paula Gillespie, editor Free Methodist World Missions - PO Box 535002, Indianapolis, IN 46253-5002 Missions Alive! staff editor: Paula J. Gillespie consultants: missionary team to Asia, Sherrill Yardy, Judy Litsey proofreaders: Linda Sanders, Jennifer Veldman artist: Lynn Hartzell Missions Alive! is a product of Free Methodist World Missions Missions Alive! © 2010 by Free Methodist World Missions NA Indianapolis, IN 46253-5002 Printed in the U.S.A. Permission is granted to copy this leader’s guide for use by local children’s leaders and educa- tors only. Please note, however, that Missions Alive! materials are copyrighted by Free Method- ist World Missions, which owns all material and illustrations. It is against the law to copy any of these materials for any commercial promotion, advertising or sale of a product or service. -

UPF Today for October 2009

FROM THE PUBLISHER Recently, the world’s attention has been focused on the General Assembly of the United Nations with its heated debates about disar- mament and the environment. The Universal Peace Federation was founded on the simple but profound premise that lasting solutions to all human problems – including poverty, hunger, and disease UPF Chairman as well as ongoing conflict, the economic crisis, and threats to the Chung Hwan Kwak environment – cannot come by political and economic efforts alone, however well intended. We absolutely need to include the spiritual UPF Co-Chair dimension, and in particular, to acknowledge the reality that we are Hyun Jin Moon all “One Family Under God.” Dr. Thomas G. Walsh, As the preamble to the UNESCO Constitution states, “wars Secretary General, Publisher begin in the minds of men,” and that is where the solutions must Universal Peace Federation Thomas G. Walsh begin – in the minds and hearts of all people, not just in the cham- bers of the United Nations and national assemblies. This principle guides all the activities of Executive Editor the Universal Peace Federation. Michael Balcomb This issue reports on observances of the UN International Day of Peace in 40 nations. This year’s theme, established by Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, was nuclear disarmament. Editor UPF held a number of disarmament seminars to mark the day, but we also conducted service Joy Pople programs, interfaith gatherings, poetry contests and sports competitions all aimed at bringing Designer a more personal element into the celebration. During the UN General Assembly week, UPF Kensei Ito also held top-level meetings with the heads of a number of delegations to the United Nations, including Kenya, Tanzania, Palau, and Nepal. -

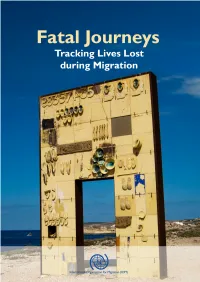

Fatal Journeys Tracking Lives Lost During Migration

IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. The opinions expressed in the book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the book do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. Publisher: International Organization for Migration 17 route des Morillons 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Tel: + 41 22 717 91 11 Fax: + 41 22 798 61 50 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.iom.int ISBN 978-92-9068-698-9 © 2014 International Organization for Migration (IOM) Cover Photo: Overlooking the Mediterranean Sea from Lampedusa’s coastline stands Porta di Lampedusa - Porta d’Europa. Created by artist Mimmo Paladino in 2008, this monument is dedicated to those migrants who have died in search of a new life. Photo by Paolo Todeschini, 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

Chronology of the Life and Works of True Parents ~ Guide to the Chronology

Chronology of the Life and Works of True Parents ~ Guide to the Chronology 1. Major providential events and achievements that True Parents initiated or conducted are recorded in order of date. If no precise date is known the entry is marked n.d. 2. In choosing which events to include, priority was given to events that True Parents directly presided over or participated in. 3. For conferences, the date indicates when the event began or the day on which True Parents attended. For international speaking tours, dates reflect the full span of the tour plus the day on which True Parents arrived in the country. 4. Where dates on the lunar calendar or heavenly calendar are included, they are written in a shortened form, with the month and date, followed by LC for lunar calendar or HC for heavenly calendar. For example, l .13 HC would mean the 13th day of the l st month by the heavenly calendar. 5. To look up material related to itemized events in the Cheon 11 Guk scriptures, the number of the corresponding page and extract number are indicated for content that can be found in Chambumo Gyeong and Cheon Seong Gyeong, and for Pyeong Hwa Gyeong the beginning page number of the speech that contains the related material is listed. For example, [CBG 122-6) refers the reader to excerpt number 6 on page 122 of Chambumo Gyeong. [CSG 1240- 22) refers the reader to excerpt number 22 on page 1240 of Cheon Seong Gyeong; and [PHG 20 I] informs the reader that related content may be found in a speech beginning on page 201 of Pyeong Hwa Gyeong. -

View/Save PDF Version of This Document

IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. The opinions expressed in the book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the book do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. Publisher: International Organization for Migration 17 route des Morillons 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland Tel: + 41 22 717 91 11 Fax: + 41 22 798 61 50 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.iom.int © 2014 International Organization for Migration (IOM) Cover Photo: Overlooking the Mediterranean Sea from Lampedusa’s coastline stands Porta di Lampedusa - Porta d’Europa. Created by artist Mimmo Paladino in 2008, this monument is dedicated to those migrants who have died in search of a new life. Photo by Paolo Todeschini All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 58_14 Fatal Journeys Tracking Lives Lost during Migration Edited by Tara Brian and Frank Laczko International Organization for Migration (IOM) Fatal Journeys: Tracking Lives Lost during Migration Table of Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................ -

Ligue 1 Economic Leader

OL, Ligue 1 economic leader Lyon, 24 March 2009 OL, Ligue 1 economic leader The 2007-08 annual report published by the financial regulatory body of the French football league (Direction Nationale du Contrôle de Gestion) on 12 March has confirmed the economic performance of Olympique Lyonnais and its determining impact on the cumulative economic results of Ligue 1. For the 2007-08 season OL, who prepare their consolidated financial statements in accordance with IFRS, as adopted by the European Union, accounted for a major share of the total Ligue 1 financial statements and remains the principal economic driver in the development of French football. For the 2007-08 season Olympique Lyonnais accounted for: 64% of the cumulative net profit of the 20 Ligue 1 clubs, with €20.1m 50% of the net cash reserves of the 20 Ligue 1 clubs, with €100.5m 47% of the shareholders’ equity of the 20 Ligue 1 clubs, with €164.8m 31% of the total amount spent on player acquisitions for the season, with €78.3m Red Cross and OL Fondation partnership OL Fondation and the French Red Cross have set up a joint programme for the training of young sportspeople in first aid techniques. A DVD to raise awareness has been produced in partnership with the Fondation du Football and involving international OL players Sidney Govou and Corine Franco. 3,000 DVDs will be distributed, including 1,500 to all amateur football clubs in the Rhône-Alpes league. OL participation in the 2009 Peace Cup After the first three competitions held in South Korea, the fourth Peace Cup will be held in Spain from 24 July to 2 August 2009, in Madrid and four cities of Andalusia (Seville, Malaga, Jerez and Huelva). -

Audio Scripts for the Kitchen

1 Audio Scripts for Pealta House exhibits: Friends of Peralta Hacienda Historical Park, Holly Alonso 525-0712 [email protected] Peralta Hacienda Audio Scripts KITCHEN Stop Speaker/Title Script Duration 1 Mission farm On the plaza at the mission at Carmel. This is Junipero 1:20 workers, Serra, head of the California missions... 1770. Actor: Quoted from the ....From the Indians who are living a little distance from Ogie correspondence of here I received, today, word that they are busy with their Zulueta Junípero harvest...and that four days from now they will come Serrra and leave their small children with me. Of two Spaniards who married convert Christian girls at this mission, one harvested thirteen and a half bushels of white wheat, and the other six and a half bushels of bald wheat; he has, besides, his corn, and his beans are fine, and promise a good yield... 2 Sardine The reaping had to be delayed three weeks, because as 1:41 harvest, 1770. soon as it began, great schools of sardines appeared near the beach, close to the mission...Until noontime, Actor: Quoted from the they harvested wheat, and in the afternoon caught Ogie correspondence of Junípero sardines. This lasted fully twenty days without a break. Zulueta Serra Besides all the fish that was eaten by so many people-- and they came, day after day, even from far-off places— besides what we ate fresh, we still have twenty barrels filled up, salted and cleaned. After two weeks of eating fish, leaving the sardines in 2 Audio Scripts for Pealta House exhibits: Friends of Peralta Hacienda Historical Park, Holly Alonso 525-0712 [email protected] peace, they went hunting for the nests of sea birds that live in the rocks and feed on fish.