Monsignor Thomas Paul Hadden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecclesiastical Circumscriptions and Their Relationship with the Diocesan Bishop

CANON 294 ECCLESIASTICAL CIRCUMSCRIPTIONS AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP WITH THE DIOCESAN BISHOP What is the relationship of the faithful in personal ecclesiastical circumscriptions to the local diocesan bishop? OPINION The Apostolic See, in the Annual General Statistical Questionnaire, asks diocesan bishops the number of priests in the ecclesiastical circumscription of the diocese, their country of origin and whether they are diocesan or religious. The fact that the diocesan bishop is answering these questions indicates the close relationship between himself and any personal Ecclesiastical Circumscription. Canons 215 and 216 of the 1917 Code required that ecclesiastical circumscriptions be territorial within a diocese and an apostolic indult was needed, for example, to establish personal parishes for an ethnic group of the faithful. After World War II, Pope Pius XII provided for the pastoral care of refugees and migrants in his apostolic constitution Exsul Familia in 1952. Chaplains for migrants were granted special faculties to facilitate pastoral care without receiving the power of jurisdiction or governance. The Second Vatican Council admitted personal criteria in ecclesiastical organisation. The decree Christus Dominus 11 held that the essential element of a particular Church is personal, being a “portion of the people of God”. Personal factors are crucial to determine the communitarian aspect of the makeup of a community. After Vatican II, the Code of Canon Law needed revision. The Synod of Bishops in 1967 approved the principles to guide the revision of the code. The eighth principle stated: “The principle of territoriality in the exercise of ecclesiastical government is to be revised somewhat, for contemporary apostolic factors seem to recommend personal jurisdictional units. -

Abbess-Elect Envisions Great U. S. Benedictine Convent Mullen High to Take Day Pupils Denvircatholic Work Halted on Ten Projects

Abbess-Elect Envisions Great U. S. Benedictine Convent Mother Augustina Returns to Germany Next Month But Her Heart Will Remain in Colorado A grgantic Benedioine convent, a St. Walburga’s of ser of Eichstaett. That day is the Feast of the Holy Name In 1949 when Mother Augustina visited the German as Abbess will be as custodian and distributor of the famed the West, is the W jo c h o p e envisioned by Mother M. of Mary, a name that Mother Augustina bears as'' a nun. mother-house and conferred with the late Lady Abbess Ben- St. Walburga oil. This oil exudes from the bones of the Augustina Weihermuellcrp^perior of St. Walbutga’s con The ceremony will be held in St. Walburga’s parish church edicta, whom she has succeeejed, among the subjects con saint, who founded the Benedictine community and lived vent in South Boulder, as she prepares to return to Ger and the cloistered nuns of the community will witness it sidered wJs the possibility of transferring the heart of the 710-780. Many remarkable cures have been attributed many to assume her position as, Lady Abbess at the mother- ffom their private choir. order to America if Russia should:overrun Europe! to its use while seeking the intercession o f St. Walburga. house of her community in Eidistaett, Bavaria. That day, just two months hence, will mark the first At the great St. Walburga’s mother-house in Eich 'Those who have heard Mother Augustina in one of her Mother Augustina’s departure for Europe is scheduled time that an American citizen ,has returned to Europe to staett, she will be superior of 130 sisters. -

Organizational Structures of the Catholic Church GOVERNING LAWS

Organizational Structures of the Catholic Church GOVERNING LAWS . Canon Law . Episcopal Directives . Diocesan Statutes and Norms •Diocesan statutes actually carry more legal weight than policy directives from . the Episcopal Conference . Parochial Norms and Rules CANON LAW . Applies to the worldwide Catholic church . Promulgated by the Holy See . Most recent major revision: 1983 . Large body of supporting information EPISCOPAL CONFERENCE NORMS . Norms are promulgated by Episcopal Conference and apply only in the Episcopal Conference area (the U.S.) . The Holy See reviews the norms to assure that they are not in conflict with Catholic doctrine and universal legislation . These norms may be a clarification or refinement of Canon law, but may not supercede Canon law . Diocesan Bishops have to follow norms only if they are considered “binding decrees” • Norms become binding when two-thirds of the Episcopal Conference vote for them and the norms are reviewed positively by the Holy See . Each Diocesan Bishop implements the norms in his own diocese; however, there is DIOCESAN STATUTES AND NORMS . Apply within the Diocese only . Promulgated and modified by the Bishop . Typically a further specification of Canon Law . May be different from one diocese to another PAROCHIAL NORMS AND RULES . Apply in the Parish . Issued by the Pastor . Pastoral Parish Council may be consulted, but approval is not required Note: On the parish level there is no ecclesiastical legislative authority (a Pastor cannot make church law) EXAMPLE: CANON LAW 522 . Canon Law 522 states that to promote stability, Pastors are to be appointed for an indefinite period of time unless the Episcopal Council decrees that the Bishop may appoint a pastor for a specified time . -

What They Wear the Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 in the Habit

SPECIAL SECTION FEBRUARY 2020 Inside Poor Clare Colettines ....... 2 Benedictines of Marmion Abbey What .............................. 4 Everyday Wear for Priests ......... 6 Priests’ Vestments ...... 8 Deacons’ Attire .......................... 10 Monsignors’ They Attire .............. 12 Bishops’ Attire ........................... 14 — Text and photos by Amanda Hudson, news editor; design by Sharon Boehlefeld, features editor Wear Learn the names of the everyday and liturgical attire worn by bishops, monsignors, priests, deacons and religious in the Rockford Diocese. And learn what each piece of clothing means in the lives of those who have given themselves to the service of God. What They Wear The Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 In the Habit Mother Habits Span Centuries Dominica Stein, PCC he wearing n The hood — of habits in humility; religious com- n The belt — purity; munities goes and Tback to the early 300s. n The scapular — The Armenian manual labor. monks founded by For women, a veil Eustatius in 318 was part of the habit, were the first to originating from the have their entire rite of consecrated community virgins as a bride of dress alike. Belt placement Christ. Using a veil was Having “the members an adaptation of the societal practice (dress) the same,” says where married women covered their Mother Dominica Stein, hair when in public. Poor Clare Colettines, “was a Putting on the habit was an symbol of unity. The wearing of outward sign of profession in a the habit was a symbol of leaving religious order. Early on, those the secular life to give oneself to joining an order were clothed in the God.” order’s habit almost immediately. -

The Constantinian Order of Saint George and the Angeli, Farnese and Bourbon Families Which Governed It

Available at a pre-publication valid until 28th December 2018* special price of 175€ Guy Stair Sainty tienda.boe.es The Constantinian Order of Saint George and the Angeli, Farnese and Bourbon families which governed it The Boletín Oficial del Estado is pleased to announce the forthcoming publication of The Constantinian Order of Saint George and the Angeli Farnese and Bourbon families which governed it, by Guy Stair Sainty. This is the most comprehensive history of the Order from its foundation to the present, including an examination of the conversion of Constantine, the complex relationships between Balkan dynasties, and the expansion of the Order in the late 16th and 17th centuries until its acquisition by the Farnese. The passage of the Gran Mastership from the Farnese to the Bourbons and the subsequent succession within the Bourbon family is examined in detail with many hitherto unpublished documents. The book includes more than 300 images, and the Appendix some key historic texts as well as related essays. There is a detailed bibliography and index of names. The Constantinian Order of Saint George 249x318 mm • 580 full color pages • Digitally printed on Matt Coated Paper 135 g/m2 Hard cover in fabric with dust jacket SHIPPING INCLUDED Preorder now Boletín Oficial del Estado * Applicable taxes included. Price includes shipping charges to Europe and USA. Post publication price 210€ GUY STAIR SAINTY, as a reputed expert in the According to legend the Constantinian Order is the oldest field, has written extensively on the history of Orders chivalric institution, founded by Emperor Constantine the GUY STAIR SAINTY Great and governed by successive Byzantine Emperors and of Knighthood and on the legitimacy of surviving their descendants. -

Vol 5, No 80 Msgr. James D. Poole

SACRAMENTO DIOCESAN ARCHIVES Vol 5 Father John E Boll No 80 Monsignor James Dallas Poole Native of Marysville, California Priest of the Diocese of Sacramento Founding Pastor of Saint Charles Borromeo Parish, Sacramento July 18, 1918 – November 10, 1997 James Dallas Poole, son of Horatio Devore Poole and Mary Elizabeth Finnegan, was born on July 18, 1918, in Marysville, California. He was baptized on July 28, 1918 in Saint Joseph Church in Marysville by Father James Grealy. His baptismal sponsors were James and Elizabeth McElroy. Jim was confirmed by Bishop Robert Armstrong on February 15, 1931. JAMES BEGINS HIS PRIMARY EDUCATION In September 1924, at the age of 6 years, James began his primary education at Notre Dame Catholic Grammar School in Marysville which was staffed by the Notre Dame Sisters. After completing the fifth grade in 1929, Jim’s parents sent him to Saint Catherine Academy in Benicia for his three years of junior high where he graduated from the eighth grade in the spring of 1932. Photo from the St Catherine, Benicia Website Saint Catherine Academy, Benicia, California BEGINNING OF HIGH SCHOOL In September of 1932, Jim transferred to Saint Joseph College Seminary in Mountain View where he began his four years of high school, graduating in June 1936. He then began his first two years of college at Saint Joseph College from 1936 to 1938. Jim Poole was a tall, handsome and intelligent student who was also an excellent athlete. If he had chosen to enter the professional world of sports, he could have made it to the professional leagues since he had the physical height, natural skill and brilliant intelligence to be a professional baseball player. -

Year of Preparation Primer

YEAR OF PREPARATION PRIMER AN EXPLANATION OF THE ORDER, ITS HISTORY, ITS MEMBERSHIP & THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION Sovereign Military Order of St. John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta American Association 1011 First Avenue New York, NY 10022 Table of Contents Chapter 1 What is the Order of Malta Page 1 Chapter 2 The Year of Preparation Page 7 Chapter 3 The American Association Page 11 Chapter 4 Works and Ministries Page 15 Chapter 5 The Lourdes Pilgrimage Page 22 Chapter 6 A History of the Order of Malta Page 29 Chapter 7 The Daily Prayer of the Order Page 33 Chapter 8 Members of the Order: Knights Page 36 and Dames of Magistral Grace, Those in Obedience and the Professed. Appendix Our Lady of Philermo Page 44 Order of Malta American Association Year of Preparation Formation Program Chapter 1--What is the Order of Malta? This booklet is designed to give you a better understanding of the Order of Malta. With background knowledge of the Order of Malta, you will be in a better position to satisfactorily complete your year- long journey of preparation to become a member of the Order. Hopefully, many of your questions about the Order will be answered in the coming pages. The Order of Malta is a lay religious Order of the Catholic Church with 14,000 members and 80,000 volunteers across the world headed by a Grand Master who governs the Order from Rome, both as a sovereign and as a religious leader. The Order was founded over 900 years ago by Blessed Gerard, a monk and Knight, who gathered a group of men and women together to commit themselves to the assistance of the poor and the sick, and to defend and to give witness to the Catholic faith. -

Monsignor H. Jules Roos, His Legacy of Love, Hope and Faith

“ By taking the Monsignor H. Jules Roos, his Legacy of Love, Hope and Faith Monsignor Jules Roos, died on February 16, 2013 at people of Pittsburgh and the people of Chimbote.” the age of 82 after serving nearly 50 years as a Of Monsignor Roos he said, “He never, ever wa- walk together, you missionary priest of Pittsburgh among the people he vered in his conviction that the church should bring to loved so much in Chimbote Peru. His life was a power- even the poorest people the spiritual and physical ful example of the words of Saint Francis of Assisi, and medical support they need.” Monsignor Roos, ensure that the “Preach the Gospel at all times. If necessary, use he remembered, “was an example of a priest hard words.” Bishop David Zubik remembered Monsignor at work who left his country and family and went to Roos as “a humble man of great faith who proudly serve and found so much joy and so much satisfac- served Jesus Christ by answering His call to minister to tion that he just stayed. He is a priest for our day, people of Chimbote ‘the least of my for the new evan- sisters and broth- gelization.” ers.’” The entire will not walk their Church of Pitts- The funeral mass burgh, he noted, “is was celebrated on honored to have February 18 in streets alone.” raised up such a Chimbote with good and holy Bishop Francisco priest.” Piorno of the Diocese of Chim- Monsignor Roos bote as the princi- +Bishop David A. Zubik was ordained to pal Celebrant. -

The Visit of a Future Pope to Pittsburgh John C

The Visit of a Future Pope to Pittsburgh John C. Bates, Esq. The canonization on October 14, 2018 of Pope Paul VI as a saint University from which he graduated in 1930, winning the univer- occasioned memories of the arrival of then-Monsignor Giovanni sity’s annual oratorical contest in his senior year.3 He undertook Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini to Pittsburgh in Septem- graduate studies in philosophy at the University of Fribourg in ber 1951 to visit the family and the grave of Monsignor Walter Switzerland, from which he received a doctorate in 1933. He then S. Carroll – Montini’s closest American co-worker and a highly attended the North American College in Rome, taking theology at respected Vatican diplomat. the Pontifical Gregorian University, which granted him a licenti- ate in 1936. He subsequently studied canon law at the Apollinare Montini’s Background Institute and received a doctorate in January 1940. He also un- The future pope was born in Concesio in the Diocese of Brescia dertook special studies at the Universities of Tours, Florence, and in northwestern Italy on September 26, 1897. He was ordained a Perugia, and became fluent in several languages. priest in May 1920 at age 22. In 1922, he entered the service of the Vatican’s Secretariat of State in Rome, where he would work During his studies, Walter Carroll was ordained a priest in the with American Father Francis J. Spellman. In 1937, Montini was chapel of the North American College in Rome on December 8, appointed Substitute (Sostituto) Secretary for Ordinary Affairs un- 1935 by Francesco Cardinal Marchetti-Selvaggiani, the vicar of der papal Secretary of State Eugenio Cardinal Pacelli. -

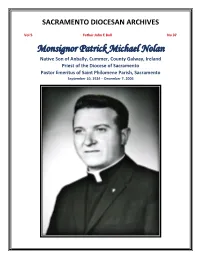

Monsignor Patrick Michael Nolan

SACRAMENTO DIOCESAN ARCHIVES Vol 5 Father John E Boll No 37 Monsignor Patrick Michael Nolan Native Son of Anbally, Cummer, County Galway, Ireland Priest of the Diocese of Sacramento Pastor Emeritus of Saint Philomene Parish, Sacramento September 10, 1924 – December 7, 2006 Patrick Michael Nolan, son of Daniel Nolan and Kate Clancy, was born on September 10, 1924 in Anbally, Cummer, County Galway, Ireland. Three days later, on September 13, he was baptized in Saint Colman’s Church, Cummer. PATRICK BEGINS HIS SCHOOLING Patrick was raised by his grandparents on their farm after his mother died when he was two years of age. He began his elementary schooling in Scoil Mhuire, Furbo, County Galway in 1931 to 1939. He then transferred to Apostolic School, Mungret College, Limerick from 1939 to 1946. He then began his theological studies at All Hallows College, Dublin where he prepared for ordination to the priesthood and service in the Diocese of Sacramento. ORDAINED A PRIEST FOR THE DIOCESE OF SACRAMENTO Patrick Nolan was ordained a priest for the Diocese of Sacramento on June 18, 1950 in All Hallows College Chapel by Bishop Michael O’Reilly of the Diocese of Saint George, Newfoundland. Photo from the book Missionary College of All Hallows, by Kevin Condon, CM All Hallows College, Dublin, Ireland 2 BEGINS PRIESTLY MINISTRY The newly arrived Father Nolan received his first assignment in the Diocese of Sacramento on November 7, 1950 when he was appointed assistant priest of Saint Bernard Parish in Eureka. At this time, Humboldt and Del Norte Counties were part of the Diocese of Sacramento. -

Directors of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions: Monsignor Paul A

Directors of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions: Monsignor Paul A. Lenz, 1976-2007 Kevin Abing, 1994 The man chosen to succeed Father Tennelly, Monsignor Paul Lenz, faced a daunting task. Somehow, he had to devise a plan which reconciled the Bureau's traditional objectives with contemporary Native American needs. Furthermore, he faced school closings, funding shortages and strained relations with the Tekakwitha Conference. Monsignor Lenz firmly and decisively met the challenges. As a result, the Bureau has been revitalized. It has resumed its active defense of Native American rights, repaired its link with the Tekakwitha Conference and extended its reach to the Native American community. Paul Lenz was born on December 15, 1925, the second of six sons of Raymond and Aimee Lenz. He spent his early life in his hometown of Gallitzin, Pennsylvania, and attended the public school there. He attended Altoona Catholic High School and graduated in 1943. He then matriculated at St. Vincent College in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. In 1946, he received a Bachelor of Arts degree in philosophy. For quite some time, Lenz had considered joining the priesthood. For a while, he even thought he might join the Maryknoll Society to do missionary work. But his plans changed when his father passed away in 1944. Lenz still wanted to become a priest, but he decided to join the diocesan clergy so he could remain close to home and help his mother. Consequently, he began his studies for the priesthood at St. Vincent's Seminary in Latrobe. On April 2, 1949, Bishop Richard T. Guilfoyle ordained Lenz in the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament in Altoona.1 For the next twenty-one years, Father Lenz occupied a variety of positions in the Altoona- Johnstown diocese. -

The Bordentown Story, 1941 – 2012 Rev

Stories of the Chicago Province Bordentown THE BORDENTOWN STORY, 1941 – 2012 Rev. Raymond Lennon PREFACE It has been a great satisfaction for me to write this history of the Divine Word Missionaries in Bordentown, New Jersey. My joy comes from the fact that Bordentown was the first Divine Word Missionary house that I entered, back in 1952, some 11 years after its foundation. It was then known as St. Joseph’s Mission House. During the two years that I spent here as a student I came to know many of the first Divine Word Missionaries who established this community as a house of studies for belated vocations. Although I was only 16 years old and was in my junior year of high school when I arrived here, I happily was considered part of the belated vocation group that was allowed to enter this program. In writing this history I have been fortunate to have access to rich, local archival information and a set of house chronicles that afford an ongoing history of what happened since the first Divine Word Missionary arrived on these grounds. I have tried to be as objective as possible in what I have written. The text is longer than I expected, and more intimate. In a way, I have been caught up in the mystique of these historic grounds, the fascinating people who lived here, and the marvelous ministry of all those who have been privileged to call Bordentown home. My hope is that these pages show you what I mean. I want to thank Fathers Patrick Connor and Leo Dusheck, Dr.