Opinion Permanent Injunction Merits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wheeler Morning Show Hosts Summary (PUBLIC) to the Following

Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 03/10/2020 03:58:13 PM EDT Mel Wheeler Inc is proud to have a wealth of talent in its morning show personalities with great longevity at the stations and in the market Leading to a strong emotional connection with our community WSLQ ? Dick Daniels David Page Dick Daniels has hosted the morning show on WSLQ for 30 years clearly giving him morning show seniority among the hosts in the Roanoke Lynchburg Market David Page currently has been co host with Dick for 20 years plus he served as WSLQ?s morning radio news anchor for two years in the mid90?s WXLK ? The Mornin? Thang with Monica Zack Antoine Zack Jackson has been entertaining morning audiences 17 years as an original member of the Mornin? Thang Monica Brooks has been part of the Mornin? Thang for 10 years after working as a Reporter on Wheeler?s Roanoke NewsTalk station WFIR WSLC ? Brett Sharp BOOMER Brett Sharp has been on WSLC 19 years coming to Roanoke to be the Program Director and Morning Show host when the station launched in early 2000 Boomer has been co hosting with Brett Sharp 9 years He started in Roanoke Radio in 1993 and has worked for several stations in this market including WXLK NAB EX 69 Wheeler Media is proud to have a wealth of talent in its morning show personalities and is even more proud of their longevity at the stations WFIR ? The Roanoke Valley?s Morning News with Joey Self Joey Self has hosted WFIR?s Morning News program 18 years He joined the Wheeler team on WFIR and WSLQ in 2001 WLNI ? The -

CAMPBELL COUNTY EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN (Revised 2015)

CAMPBELL COUNTY EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN (Revised 2015) TABLE OF CONTENTS BASIC PLAN 10 I. INTRODUCTION 11 II. PLANNING ASSUMPTIONS AND CONSIDERATIONS 13 III. ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES 14 IV. CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS 16 V. INCIDENT MANAGEMENT ACTIONS 20 VI. ONGOING PLAN MANAGEMENT 22 APPENDICIES 1. GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS 24 2. LIST OF ACRONYMS 28 3. AUTHORITIES AND REFERENCES 30 4. MATRIX OF RESPONSIBILITIES 31 5. SUCCESSION OF AUTHORITY 32 6. EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN DISTRIBUTION LIST 33 7. CONTINUITY OF GOVERNMENT 34 8. NIMS RESOLUTION 35 1 9. SAMPLE DECLARATION OF A LOCAL EMERGENCY 38 EMERGENCY SUPPORT FUNCTIONS 1. TRANSPORTATION 40 TAB A COORDINATION 42 TAB B EMERGENCY TRANSPORTATION VEHICLES 42 TAB C MEDEVAC SUPPORT 2. COMMUNICATIONS 43 TAB A SUGGESTED EOC MESSAGE FLOW 48 TAB B AMATEUR RADIO EMERGENCY SERVICE 49 TAB C USE OF CABLE TV DURING EMERGENCY SITUATIONS 50 TAB D MESSAGE LOG 51 TAB E EOC MESSAGE FORM 52 TAB F EOC SIGN IN/SIGN OUT LOG 53 TAB G EOC STAFF SCHEDULE 54 TAB H EOC STATUS BOARD 55 TAB I EMERGENCY PUBLIC INFORMATION RESOURCES 56 TAB J EMERGENCY NOTIFICATION PROCEDURES 64 3. PUBLIC WORKS, UTILITIES, INSPECTIONS, PLANNING, AND ZONING 65 TAB A PUBLIC WORKS/UTILITIES RESOURCES 71 TAB B INSPECTIONS, PLANNING AND ZONING RESOURCES 73 TAB C BUILDING POSTING GUIDE 74 2 4. FIRE FIGHTING 75 TAB A FIRE DEPARTMENT RESOURCES 79 5. EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT 83 TAB A EMERGENCY CONTACT TELEPHONE LIST 95 TAB B PRIMARY EOC STAFFING 98 TAB C EOC LAYOUT 99 6. MASS CARE, HOUSING, AND HUMAN RESOURCES 100 TAB A CAMPBELL COUNTY SCHOOLS 104 TAB B CAMPBELL COUNTY SHELTER FLOOR PLAN 105 7. -

Parent/Student Handbook 1

2012-2013 LYNCHBURG CITY SCHOOLS Parent/Student Handbook 1 Parent/Student Handbook Lynchburg City Schools 2012-2013 Map of Schools ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 School Board ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 School Districts ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 School Information .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 4-5 Directory Hours of Operation (UPDATED THIS YEAR) Inclement Weather/ School Closing .............................................................................................................................................................. 6 Wellness .................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 School Nutrition ..................................................................................................................................................................................................10 -

VAB Member Stations

2018 VAB Member Stations Call Letters Company City WABN-AM Appalachian Radio Group Bristol WACL-FM IHeart Media Inc. Harrisonburg WAEZ-FM Bristol Broadcasting Company Inc. Bristol WAFX-FM Saga Communications Chesapeake WAHU-TV Charlottesville Newsplex (Gray Television) Charlottesville WAKG-FM Piedmont Broadcasting Corporation Danville WAVA-FM Salem Communications Arlington WAVY-TV LIN Television Portsmouth WAXM-FM Valley Broadcasting & Communications Inc. Norton WAZR-FM IHeart Media Inc. Harrisonburg WBBC-FM Denbar Communications Inc. Blackstone WBNN-FM WKGM, Inc. Dillwyn WBOP-FM VOX Communications Group LLC Harrisonburg WBRA-TV Blue Ridge PBS Roanoke WBRG-AM/FM Tri-County Broadcasting Inc. Lynchburg WBRW-FM Cumulus Media Inc. Radford WBTJ-FM iHeart Media Richmond WBTK-AM Mount Rich Media, LLC Henrico WBTM-AM Piedmont Broadcasting Corporation Danville WCAV-TV Charlottesville Newsplex (Gray Television) Charlottesville WCDX-FM Urban 1 Inc. Richmond WCHV-AM Monticello Media Charlottesville WCNR-FM Charlottesville Radio Group (Saga Comm.) Charlottesville WCVA-AM Piedmont Communications Orange WCVE-FM Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCVE-TV Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCVW-TV Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corp. Richmond WCYB-TV / CW4 Appalachian Broadcasting Corporation Bristol WCYK-FM Monticello Media Charlottesville WDBJ-TV WDBJ Television Inc. Roanoke WDIC-AM/FM Dickenson Country Broadcasting Corp. Clintwood WEHC-FM Emory & Henry College Emory WEMC-FM WMRA-FM Harrisonburg WEMT-TV Appalachian Broadcasting Corporation Bristol WEQP-FM Equip FM Lynchburg WESR-AM/FM Eastern Shore Radio Inc. Onley 1 WFAX-AM Newcomb Broadcasting Corporation Falls Church WFIR-AM Wheeler Broadcasting Roanoke WFLO-AM/FM Colonial Broadcasting Company Inc. Farmville WFLS-FM Alpha Media Fredericksburg WFNR-AM/FM Cumulus Media Inc. -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

Linda Kenney Baden, Esq. Address

CURRICULUM VITAE Personal Data: Name: Linda Kenney Baden, Esq. Address: 15 West 53rd Street New York, New York 10019 Legal: Pro Bono: Assisted the IP on numerous cases advising regarding non-DNA forensic issues. Cases included: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Anthony Wright which was tried and resulted in an acquittal of a murder charge (contact person Peter Neufeld, Esq.). Recent Cases of Note: Commonwealth v. Aaron Hernandez, represented Aaron Hernandez as forensic counsel on double homicide trial for which he was acquitted. State of New York v. Gilberto Nunez, assisted trial counsel on forensic and scientific issues resulting in a not guilty verdict on a murder charge for Dr. Nunez. State of New York v. Gigi Jordan, as legal forensic consultant to the trial team where she was acquitted by the State of New York of a murder charge but was convicted for the crime of manslaughter in the death of her minor child. State of Florida v. Casey Anthony, represented Casey Anthony on a pro bono basis as the forensic advisor/attorney for the defense from December 2008 until October 2010, resigning only because the State of Florida would not fund costs to out of state pro bono counsel. In re Estate of Madeleine Stockdale, after nearly ten years of litigation including a decision by the NJ Supreme Court, the Superior Court of New Jersey, Chancery Division, Probate Part, in June 2010, granting a seven figure fee award, praised Ms. Kenney Baden and her co-counsel as extremely capable for their persistent, extraordinary efforts and the results which they obtained in a ten year fight on behalf of the Spring Lake First Aid Squad. -

Station Ownership and Programming in Radio

FCC Media Ownership Study #5: Station Ownership and Programming in Radio By Tasneem Chipty CRA International, Inc. June 24, 2007 * CRA International, Inc., 200 Clarendon Street, T-33, Boston, MA 02116. I would like to thank Rashmi Melgiri, Matt List, and Caterina Nelson for helpful discussions and valuable assistance. The opinions expressed here are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of CRA International, Inc., or any of its other employees. Station Ownership and Programming in Radio by Tasneem Chipty, CRA International, June, 2007 I. Introduction Out of concern that common ownership of media may stifle diversity of voices and viewpoints, the Federal Communications Commission (“FCC”) has historically placed limits on the degree of common ownership of local radio stations, as well as on cross-ownership among radio stations, television stations, and newspapers serving the same local area. The 1996 Telecommunications Act loosened local radio station ownership restrictions, to different degrees across markets of different sizes, and it lifted all limits on radio station ownership at the national level. Subsequent FCC rule changes permitted common ownership of television and radio stations in the same market and also permitted a certain degree of cross-ownership between radio stations and newspapers. These changes have resulted in a wave of radio station mergers as well as a number of cross-media acquisitions, shifting control over programming content to fewer hands. For example, the number of radio stations owned or operated by Clear Channel Communications increased from about 196 stations in 1997 to 1,183 stations in 2005; the number of stations owned or operated by CBS (formerly known as Infinity) increased from 160 in 1997 to 178 in 2005; and the number of stations owned or operated by ABC increased from 29 in 1997 to 71 in 2005. -

TITLE Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (83Rd, Phoenix, Arizona, August 9-12, 2000)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 447 546 CS 510 463 TITLE Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (83rd, Phoenix, Arizona, August 9-12, 2000). Radio-Television Journalism Division. INSTITUTION Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication. PUB DATE 2000-08-00 NOTE 168p.; For other sections of this proceedings, see CS 510 451-470. PUB TYPE Collected Works Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Content Analysis; Economic Factors; Editing; Empowerment; Higher Education; Journalism; *Journalism Education; News Media; *News Reporting; Ownership; Race; Radio; Social Class; *Television; Videotape Recordings IDENTIFIERS Deregulation; Local Television Stations; Writing Style ABSTRACT The Radio-Television Journalism Division section of the proceedings contains the following six papers: "Local Television News and Viewer Empowerment: Why the Public's Main Source of News Falls Short" (Denise Barkis Richter); "For the Ear to Hear: Conversational Writing on the Network Television News Magazines"(C. A. Tuggle, Suzanne Huffman and Dana Rosengard); "Synergy Bias: Conglomerates and Promotion in the News" (Dmitri Williams); "Constructing Class & Race in Local TV News" (Don. Heider and Koji Fuse); "Going Digital: An Exploratory Study of Nonlinear Editing Technology in Southeastern Television Newsrooms" (Seok Kang, George L. Daniels, Tanya Auguston and Alyson Belatti); and "Deregulation and Commercial Radio Network News: A Qualitative Analysis" (Richard Landesberg).(RS) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ;t- Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (83rd, Phoenix, Arizona, August 9-12, 2000). Radio-Television Journalism Division. -

How to Switch Programs on the XDS Pro Using Serial Commands Every

How to switch programs on the XDS Pro using Serial Commands Every Program transmitted via the XDS satellite system is associated with a Program ID that identifies the program to the receiver. Individual programs may be selected to the receiver’s output ports by issuing serial ID commands via the M&C (Console) Port on the back of the receiver, thereby changing the program that the receiver is decoding. If a program is selected for decoding using this method that is NOT part of the station’s list of authorized programming, it will NOT be decoded. Only programs authorized for the station that the receiver is assigned to can be decoded. Whenever possible, always use the XDS Port Scheduler as your main method of taking a program to ensure you receive the proper content. You can command the receiver as follows: 1) Start a terminal session (using HyperTerminal or equivalent) by connecting to the receiver’s M&C (Console) Port. The default settings for this Port are 115200, 8, None, 1. 2) Hit Enter. You should see a “Hudson” prompt. 3) Log in by by typing LOGIN(space)TECH(space)(PASSWORD) (Use your Affiliate NMS (myxdsreceiver.westwoodone.com) password OR you can use the receiver’s daily password (Setup > Serial # > PWD). 4) Login confirmation will be displayed (‘You are logged in as TECH’) Once you are logged in, the command to steer a Port on the receiver to a specific program PID is: PORT(space)LIVE,(Port),ID Examples: PORT LIVE,A,99 – This command will set Port A to Program ID 99 (Mark Levin) PORT LIVE,B,1196 – This command will set Port B to Program ID 1196 (CBS Sports - Tiki and Tierney) Please refer to the PID table listed below for the Program ID assignments for each program available on the Westwood One XDS receiver. -

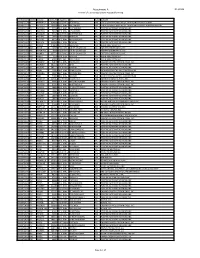

Attachment a DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing

Attachment A DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing File Number Service Callsign Facility ID Frequency City State Licensee 0000072254 FL WMVK-LP 124828 107.3 MHz PERRYVILLE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMN. 0000072255 FL WTTZ-LP 193908 93.5 MHz BALTIMORE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 0000072258 FX W253BH 53096 98.5 MHz BLACKSBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072259 FX W247CQ 79178 97.3 MHz LYNCHBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072260 FX W264CM 93126 100.7 MHz MARTINSVILLE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072261 FX W279AC 70360 103.7 MHz ROANOKE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072262 FX W243BT 86730 96.5 MHz WAYNESBORO VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072263 FX W241AL 142568 96.1 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072265 FM WVRW 170948 107.7 MHz GLENVILLE WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072267 AM WESR 18385 1330 kHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072268 FM WESR-FM 18386 103.3 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072270 FX W289CE 157774 105.7 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072271 FM WOTR 1103 96.3 MHz WESTON WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072274 AM WHAW 63489 980 kHz LOST CREEK WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072285 FX W206AY 91849 89.1 MHz FRUITLAND MD CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. 0000072287 FX W284BB 141155 104.7 MHz WISE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072288 FX W295AI 142575 106.9 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072293 FM WXAF 39869 90.9 MHz CHARLESTON WV SHOFAR BROADCASTING CORPORATION 0000072294 FX W204BH 92374 88.7 MHz BOONES MILL VA CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. -

UPDATED 4.15.2015 TIME: 9:00 A.M. ET APRIL 18, 2015 1. Call to Order

UPDATED 4.15.2015 AGENDA SOCIETY OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISTS BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING TIME: 9:00 A.M. ET APRIL 18, 2015 INDIANAPOLIS STREAMED LIVE AT WWW.SPJ.ORG 1. Call to Order – Neuts 2. Roll Call – Walsh a. Cuillier g. Tarquinio n. Koretzky t. Johnson b. Neuts h. Gass-Poore o. Gallagher- u. Hallenberg c. Fletcher i. Brett Hall Newberry v. Matthew d. Kopen- j. Reilley p. Givens Hall Katcef k. Tallent q. Radske w. Hernandez e. Walsh l. Baker r. McLean f. McCloskey m. Schotz s. Gallagher 3. Report of the SPJ President – Neuts [Page 2] 4. Approval of Board Meeting Minutes – Neuts a. Sept. 4, 2014 [Page 5] b. Sept. 7, 2014 [Page 11] c. Nov. 18, 2014 [Page 15] 5. Review of the SPJ budget for fiscal year ending July 31, 2016. – Skeel [Page 21] 6. Chapter Activity – Puckey [Page 36] 7. Nominations Report – Albarado [Page 37] 8. Report of the SDX Foundation President – Leger [Page 38] 9. Staff Report – Skeel [Page 40] 10. Action/Discussion Items a. Convention – Skeel [Page 51] i. Discuss moving to June, July, October ii. Discuss criteria for city selection b. Online LDF Auction – Skeel c. Meetings recording policy – Skeel d. Religious Freedom legislation, as it affects SPJ – Neuts and Fletcher e. SPJ Diversity – Neuts Page 1 of 2 11. Old/New Business a. Financial implications of extended post-grad discount to 4 years – Skeel [Page 54] b. Career center update – Walsh c. Communities update – Neuts [Page 56] d. Tech upgrade update – Puckey [Page 58] e. Update re high school journalism book – Tallent f. -

Robert J. Marks II

Robert J. Marks II Curriculum Vitae Amplified (Abbreviated CV also available: check for hyperlinks) July 13, 2021 Contents 1 Education 5 2 Contact Information 5 3 Employment History 5 4 Recognition 6 4.1 Honors & Awards ................................. 6 4.2 Listings ...................................... 7 4.3 Honorary Conference Positions ......................... 10 5 Professional Societies 11 5.1 Publication Administration ........................... 11 5.2 Administrative .................................. 11 5.3 Conferences .................................... 14 6 Publications 18 6.1 Books ....................................... 18 6.2 Book Chapters .................................. 19 6.3 Journal Articles .................................. 25 6.3.1 1970-1979 ................................. 25 6.3.2 1980-1989 ................................. 26 6.3.3 1990-1999 ................................. 29 6.3.4 2000-2009 ................................. 34 6.3.5 2010-2019 ................................. 37 1 CONTENTS Curriculum Vitae 6.3.6 2020-2029 ................................. 41 6.4 Proceedings & Edited Publications ....................... 42 6.4.1 1970-1979 ................................. 42 6.4.2 1980-1989 ................................. 43 6.4.3 1990-1999 ................................. 46 6.4.4 2000-2009 ................................. 53 6.4.5 2010-2019 ................................. 58 6.4.6 2020-2029 ................................. 66 6.5 Patents ...................................... 68 6.6 Endorsements