Downloaded 2021-09-28T00:05:27Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Was Who in Early Modern Limerick by Alan O'driscoll and Brian Hodkinson

Who Was Who in Early Modern Limerick By Alan O'Driscoll and Brian Hodkinson The following was commenced by Alan O’Driscoll (AOD) while on a work placement in Limerick Museum in the autumn of 2012 and continued by Brian Hodkinson. It is a continuation of the Who was who in medieval Limerick, which can also be found on the Limerick Museum website. It straddles the period c 1540 to c 1700, so some figures may appear in both databases. It is compiled for the most part by using the indexes of the various sources using Limerick as the search term. However, it has been noted that these indexes are often not comprehensive, and so when sources are available online, then a scroll through the text highlighting Limerick has produced entries not in the index. Such scrolling has also found entries where place names are abviously Limerick ones but Limerick does not appear as a word, e.g. in Fiants and CPCRCI. So while I (BJH) like to think it is comprehensive, it may not be. Notes. • Where two similar names are believed to be the same person, the entries are combined. However, many repeated names appear in the same lists (particularly in the Civil Survey). Where this occurs and/or the two persons are listed as coming from a different location, they are separated, even if they are recorded at the same time. There are a great many repeated full names, such as William Bourke, and it has proved practically impossible to be sure of which of these are different people. -

Proposed Record of Protected Structures Newcastle West Municipal District

DRAFT LIMERICK DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2022-2028 Volume 3B Proposed Record of Protected Structures Newcastle West Municipal District June 2021 Contents 1.0 Introduction Record of Protected Structures (RPS) – Newcastle West Municipal District 1 2.0 Record of Protected Structures - Newcastle West Municipal District ................................. 2 1 1.0 Introduction Record of Protected Structures (RPS) – Newcastle West Municipal District Limerick City & County Council is obliged to compile and maintain a Record of Protected Structures (RPS) under the provisions of the Planning and Development Act 2000 (as amended). A Protected Structure, unless otherwise stated, includes the interior of the structure, the land lying within the curtilage of the structure, and other structures lying within that curtilage and their interiors. The protection also extends to boundary treatments. The proposed RPS contained within Draft Limerick Development Plan 2022 - 2028 Plan represents a varied cross section of the built heritage of Limerick. The RPS is a dynamic record, subject to revision and addition. Sometimes, ambiguities in the address and name of the buildings can make it unclear whether a structure is included on the RPS. Where there is uncertainty you should contact the Conservation Officer. The Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht is responsible for carrying out surveys of the architectural heritage on a county-by-county basis. Following the publication of the NIAH for Limerick City and County, and any subsequent Ministerial recommendations, the Council will consider further amendments to the Record of Protected Structures. The NIAH survey may be consulted online at buildingsofireland.ie There are 286 structures listed as Protected Structures in the Newcastle West Metropolitan District. -

Limerick Manual

RECORD OF MONUMENTSAND PLACES as Established under Section 12 of the National Monuments ’ (Amendment)Act 1994 COUNTYLIMERICK Issued By National Monumentsand Historic Properties Service 1997 j~ Establishment and Exhibition of Record of Monumentsand Places under Section 12 of the National Monuments (Amendment)Act 1994 Section 12 (1) of the National Monuments(Amendment) Act 1994 states that Commissionersof Public Worksin Ireland "shall establish and maintain a record of monumentsand places where they believe there are monumentsand the record shall be comprised of a list of monumentsand such places and a mapor mapsshowing each monumentand such place in respect of each county in the State." Section 12 (2) of the Act provides for the exhibition in each county of the list and mapsfor that county in a mannerprescribed by regulations madeby the Minister for Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht. The relevant regulations were made under Statutory Instrument No. 341 of 1994, entitled National Monuments(Exhibitior~ of Record of Monuments)Regulations, 1994. This manualcontains the list of monumentsand places recorded under Section 12 (1) of the Act for the Countyof Limerick whichis exhibited along with the set of mapsfor the Countyof Limerick showingthe recorded monumentsand places. Protection of Monumentsand Places included in the Record Section 12 (3) of the Act provides for the protection of monumentsand places included in the record stating that "When the owner or occupier (not being the Commissioners) of monumentor place which has been recorded under -

Pairc Lde Naola Chill De

Pairclde Naola Chill lde In October1980 the local newspapersheralded Killeedy's A field the property of Kantoher C.D.S.was mad'eavailible to the club breakthroughin capturing-headlinestheir fiisf couqtysenior hu-rling-ti- at a nominal fee in the earlv seventies tle with anarietvhv of - "sensationalWin for courtesy of the managemeit commit- Killeedy", "The iedr of the underdog","first for Killeedy" tee - it was in this field that organised --they failed on thr-ee scientific training was first employed etc. An"dsensatioiral it was indeed had by Killeedy G.A.A.leading to their first previousattempts and this one lookedlike going too. But county final appearancein 1973and to iacluck was with them and so the county cup resided in their first divisional senior title in 1974. forecasting Inclement weather at times forced the Killeedyduring the Wintermonths and many wg_Ie club to train indoors in Cronin's hall on a longilomocil-e for the JohnDaly Cupin fhe WestLimerick the Community centre and oftentimes parish. road trainins was adopted. And *hen these same Recent veErs have Seenteam train- newsDaDers the headlines ing sessioirsback again in Hennessy's carried By JosephO'Connor farm in Killeedv which had been used "KiU'eeily's reign as champs in s earlier this ceniurv also bv the club - short-lived" and "Killeedy's reign on this occasion howevei a different brought to an end" just nine field was usedwhich carries with it the months later in July 1981 many Situated just below Dore's house,now distinction of being ideally suited to might have felt Killeedy were only owned by James Mulcahy, this field training irrespective of weather condi- fluke winners and a team of the was constantly used for hurling and tions or time of the year. -

Church of Ireland Parish Registers

National Archives Church of Ireland Parish Registers SURROGATES This listing of Church of Ireland parochial records available in the National Archives is not a list of original parochial returns. Instead it is a list of transcripts, abstracts, and single returns. The Parish Searches consist of thirteen volumes of searches made in Church of Ireland parochial returns (generally baptisms, but sometimes also marriages). The searches were requested in order to ascertain whether the applicant to the Public Record Office of Ireland in the post-1908 period was entitled to an Old Age Pension based on evidence abstracted from the parochial returns then in existence in the Public Record Office of Ireland. Sometimes only one search – against a specific individual – has been recorded from a given parish. Multiple searches against various individuals in city parishes have been recorded in volume 13 and all thirteen volumes are now available for consultation on six microfilms, reference numbers: MFGS 55/1–5 and MFGS 56/1. Many of the surviving transcripts are for one individual only – for example, accessions 999/562 and 999/565 respectively, are certified copy entries in parish registers of baptisms ordered according to address, parish, diocese; or extracts from parish registers for baptismal searches. Many such extracts are for one individual in one parish only. Some of the extracts relate to a specific surname only – for example accession M 474 is a search against the surname ”Seymour” solely (with related names). Many of the transcripts relate to Church of Ireland parochial microfilms – a programme of microfilming which was carried out by the Public Record Office of Ireland in the 1950s. -

A.L NON-TECHNICALSUMMARY

«or-toner Pc vlt-v IPPC Mulllan e A.l NON -TECHNICAL SU M MARY The a pplic ation tor an IPPC licence is being put torward by NRGE (Nutrient Recovery to Generate Electricity) Ltd, whose registered office is at Mooresfort. Lattin, Co. Tipperary. Thisapplication has been prepared and submitted by NRGE on behalf of Mary Mullane Killeedy Ballag h, Co, Limerick, The farm operates as a c ontract growers for the Kantoher Poultry Producers Co operative Society. All stock, feed, finished poultry and waste arrangementsare managed and c ontrolled centrally by fhe co-op. The farm operates under standard methodology approved by An Bord Bia. The farm comprises 2 poultry houses of modern design wh ich are operated to the highest standard. All clean storm w ater from the site is collected via the sformwater c ollec tion system, before discharge. Monitoring points are visually inspected weekly. All soiled water is diverted into the adjac ent sforage tan ks. The estimated annua l production of poultry lifter from fhe farm is 240 tonnes The farm employs one farmer. The farm also gives rise indirecfly to another 5 jobsin the meat processing , milling and service sectors. The application of animal manure to farmland isregulated under 5.1. No. 378 of 2006 and distribu tion of manure from thissite will comply with fhose regulations. This farm is For inspection purposes only. entitled to supply manure to Consentany lofocal copyrightfarme ownerr required w ho forwants any otherit. use.and isobliged to record all dispatches from the holding and the farmers acq uiring manure are obliged to rec ord all consignments acquired and to use it in compliance with the regulations. -

Round About the County of Limerick

ROUND ABOUT THE COUNTY OF LIMERICK: BY REV. JAMES DOW'D, A.B., AUTHOR OF "LIMERICK AXD ITS SIEGES." Zfnterick : G. McKERN & SONS, PUBLISHERS. PREFACE. INasking my readers to accompany me on an Historical and Archzological Tour Round About the County of L~merick,I have consulted their convenience by grouping events around the places brought under notice. The arrangement may lead to occasional repetition, and the narrative may sometimes be left incomplete, to bf resumed and finished elsewhere. But, on the o ?r hand, it possesses the undoubted advantage of fixlng the % FRINTED BY attention of the reader upon the events and occur- e. W'KERN AND SONS, LINERICK. rences which render the places visited memorable. This little work 1s intended to be, as far as possible, a history of those places in the County of Limerick about which there is something to be told. The length of time covered ranges from the pre-historic period almost up to the present. Around the hill of Knockainy linger memories of the last remnants , of an extinct race. The waters of Lough Gur and the adjacent swamps y~eldup remains of animals no longer to be found in th~scountry. The same district preserves the rude memorials of men of the Stone Age whose cromlechs, circles and pillar stones have survived all the changes and chances of the inter- vening centuries. The vigorous heathenism of the early Celts has bequeathed the names of its last heroes to several of the more noticeable physical features of the county, To them succeeded the VI. -

The List of Church of Ireland Parish Registers

THE LIST of CHURCH OF IRELAND PARISH REGISTERS A Colour-coded Resource Accounting For What Survives; Where It Is; & With Additional Information of Copies, Transcripts and Online Indexes SEPTEMBER 2021 The List of Parish Registers The List of Church of Ireland Parish Registers was originally compiled in-house for the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI), now the National Archives of Ireland (NAI), by Miss Margaret Griffith (1911-2001) Deputy Keeper of the PROI during the 1950s. Griffith’s original list (which was titled the Table of Parochial Records and Copies) was based on inventories returned by the parochial officers about the year 1875/6, and thereafter corrected in the light of subsequent events - most particularly the tragic destruction of the PROI in 1922 when over 500 collections were destroyed. A table showing the position before 1922 had been published in July 1891 as an appendix to the 23rd Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records Office of Ireland. In the light of the 1922 fire, the list changed dramatically – the large numbers of collections underlined indicated that they had been destroyed by fire in 1922. The List has been updated regularly since 1984, when PROI agreed that the RCB Library should be the place of deposit for Church of Ireland registers. Under the tenure of Dr Raymond Refaussé, the Church’s first professional archivist, the work of gathering in registers and other local records from local custody was carried out in earnest and today the RCB Library’s parish collections number 1,114. The Library is also responsible for the care of registers that remain in local custody, although until they are transferred it is difficult to ascertain exactly what dates are covered. -

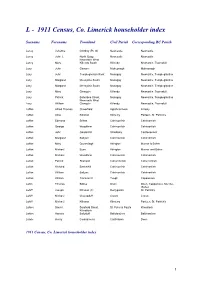

1911 Census, Co. Limerick Householder Index

L - 1911 Census, Co. Limerick householder index Surname Forename Townland Civil Parish Corresponding RC Parish Lacey Johanna Gortboy (Pt. of) Newcastle Newcastle Lacey John J. North Quay, Newcastle Newcastle Newcastle West Lacey Mary Killeedy South Killeedy Newcastle, Tournafull Lacy John Garrane Mahoonagh Mahoonagh Lacy John Templeglentan West Monagay Newcastle, Templeglantine Lacy Margaret Meenyline South Monagay Newcastle, Templeglantine Lacy Margaret Meenyline South Monagay Newcastle, Templeglantine Lacy Mary Glenquin Killeedy Newcastle, Tournafull Lacy Patrick Boherbee Street, Monagay Newcastle, Templeglantine Newcastle West Lacy William Glenquin Killeedy Newcastle, Tournafull Laffan Alfred Thomas Cloverfield Aglishcormack Kilteely Laffan Alice Killonan Kilmurry Parteen, St. Patrick's Laffan Edmond Brittas Cahirconlish Cahirconlish Laffan George Woodfarm Cahirconlish Cahirconlish Laffan John Gardenhill Stradbally Castleconnell Laffan Margaret Ballyart Cahirconlish Cahirconlish Laffan Mary Dromeliagh Abington Murroe & Boher Laffan Michael Eyon Abington Murroe and Boher Laffan Michael Woodfarm Cahirconlish Cahirconlish Laffan Patrick Skahard Caherconlish Caherconlish Laffan Richard Baskethill Cahirconlish Cahirconlish Laffan William Ballyart Cahirconlish Cahirconlish Laffan William Tinnatarriff Tuogh Cappamore Laffin Thomas Bilboa Doon Doon, Cappamore, Murroe, Boher Lahiff Joseph Killonan (1) Derrygalvin St. Patrick's Lahiff Michael Cloonaduff Croom Croom Lahiff Michael Killonan Kilmurry Parteen, St. Patrick's Lahive Daniel Sarsfield -

Limerick Guide

THE BEST OF IRELAND Series LimerickStanding on the Shoulders of Giants! COMPLIMENTARY COPY COMPLIMENTARY INCLUDES MAP A Must See Destination for 2015 Limerick Guide Lotta stories in this town. This town. This old, bold, cold town. This big town. This pig town. “Every house a story…This gets up under your skin town…Fill you with wonder town…This quare, rare, my ho-o-ome is there town. Full of life town. Extract from Pigtown by local playwright, Mike Finn. Editor: Rachael Finucane Contributing writers: Rachael Finucane, Bríana Walsh and Cian Meade. Photography: Lorcan O’Connell, Dave Gaynor, Limerick City of Culture, Limerick Marketing Company, Munster Images, Tarmo Tulit, Rachael Finucane and others (see individual photos for details). 2 | The Best Of Ireland Series Limerick Guide Contents THE BEST OF IRELAND Series Contents 4. Introducing Limerick 29. Festivals & Events 93. Further Afield 6. Farewell National 33. Get Active in Limerick 96. Accommodation City of Culture 2014 46. Family Fun 98. Useful Information/ 8. History & Heritage Services 57. Shopping Heaven 17. Arts & Culture 100. Maps 67. Food & Drink A Tourism and Marketing Initiative from Southern Marketing Design Media € For enquiries about inclusion in updated editions of this guide, please contact 061 310286 / [email protected] RRP: 3.00 No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the publishers. © Southern Marketing Design Media 2015. Every effort has been made in the production of this magazine to ensure accuracy at the time of publication. The editors cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions, or for any alterations made after publication. -

NCW Abbey Drom A3

Newcastle West Abbeyfeale Dromcollogher Newcastle West is Limerick’s largest town and located Situated in the West Limerick uplands, Abbeyfeale is Dromcollogher was one of the in the middle of a great bowl-shaped valley in West the westernmost town in the county and is around 900 starting points for the Irish years old. Co-op Movement, with the Limerick, known one time as the valley of the Wild Boar. The crest of the town carries the image of a wild boar. first Co-operative creamery Mainistir na Féile, meaning “Abbey of the Feale” is named being set up here in 1889 Desmond Banqueting Hall and Castle Newcastle West’s after the former Cistercian monastery which was located on the initiative of Horace adjacent to the current town square and is a historical landmark feature dominates the southern end of the Main Plunkett. The listed building has since been restored, market town. The Abbey has since all but disappeared, and is now the National Dairy Co-operative Museum. Town Square. The banqueting hall of the Desmond Castle, and the only identifiable remnants are those used in the seat of the Earl of Desmond, parts of which date from construction of the Roman Catholic Church in 1847. Dromcollogher Fire the 13th century. The Current Castle dates from the 15th Dromcollogher is also widely known for its tragic past. century. We will journey through the town centre, taking in its monastic and infrastructural development and some of On 5 September 1926, a timber barn being used as a Castle Demesne 99 acres of parkland with numerous forms its buildings of architectural merit. -

Placenames of the Down Survey of Co

Placenames of the Down Survey of Co. Limerick. Compiled by Brian Hodkinson, Limerick Museum, June 2013. http://downsurvey.tcd.ie/down-survey-maps.php#c=Limerick&indexOfObjectValue=- 1&indexOfObjectValueSubstring=-1 The following is a list of the placenames of the Down Survey, taken for the most part from the parish maps. It is not an exhaustive list of every occurrence of a particular spelling. The list was compiled from the TCD website in the order presented there, i.e. by Barony then by parish within the Barony, Only the first noted occurrence of a spelling of a name is given and it is possible several other maps contain the same spelling. Thus the first entry might be peripheral, e.g. the name of the adjoining parish and more detail is available on another map. Where there are numbers on parcels of land, rather than names on the map, the associated terrier has been mined for the name. It is quite possible, however, that there are other variant spellings of names on the map within the terriers. For some Baronies there are no parish maps, so names are taken from the Barony map. The list was made for my own research purposes and is made available with that understanding. It is probably in almost alphabetical order. OW-Owneybeg CL-Coshlea CW-Clanwilliam CO-Coonagh KM-Kilmallock CM-Connello SC-Small County PB-Pubblebrien LB-Liberties of Limerick CM-Coshma KY-Kenry A Abbybalinegaule Athneasy & CL Kilbreedy Abbyfeild Abbeyfeale Cn Abbyony Abington CW Abbyowny Clonkeen CW Abbyowthneybeg Abington OW Ackarakeele Oola & CO Tuoghcluggin Adamstowne