The Case of Chitharal in Tamil Nadu, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kalarippayat

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/65537 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-07 and may be subject to change. Kalarippayat The structure and essence of an Indian martial art D.H. Luijendijk Kalarippayat The Structure and Essence of an Indian Martial Art Een wetenschappelijke proeve op het gebied van de Religiewetenschappen Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. mr. S.C.J.J. Kortmann volgens besluit van het College van Decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 16 april 2008 om 15.30 uur precies door Dick Hidde Luijendijk geboren op 19 juni 1971 te Gouda Promotor: Prof. dr. W. Dupré Copromotor: Dr. P.J.C.L. van der Velde Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. G. Essen Prof. dr. W.M. Callewaert (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven) Dr. F.L. Bakker (Universiteit Utrecht) CIP-GEGEVENS KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG © Copyright D.H. Luijendijk 2007 Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag zonder schriftelijke toestemming van de auteur worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij electronisch, mechanisch, door fotokopieen, opnamen, of op enig andere manier. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the author. -

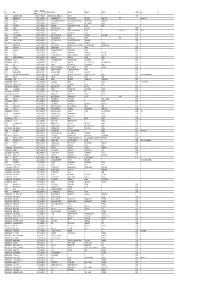

Mgl-Di419-Unpaid Shareholder List As On

DIVIDEND WARRANT KEY NAME MICR DDNO ADDRESS 1 ADDRESS 2 ADDRESS 3 ADDRESS 4 CITY PINCODE JH1 JH2 AMOUNT NO 001221 DWARKA NATH ACHARYA 220000.00 194000027 843427 5 JAG BANDHU BORAL LANE CALCUTTA 700007 000642 JNANAPRAKASH P.S. 2200.00 194000030 536 POZHEKKADAVIL HOUSE P.O.KARAYAVATTAM TRICHUR DIST. KERALA STATE 68056 MRS. LATHA M.V. 000691 BHARGAVI V.R. 2200.00 194000031 537 C/O K.C.VISHWAMBARAN,P.B.NO.63 ADV.KAYCEE & KAYCEE AYYANTHOLE TRICHUR DISTRICT KERALA STATE 002670 SUNIL P K 6600.00 194000040 546 PARAMEL HOUSE CHIRAKKACODE VELLANIKKARA P O THRISSUR 002679 NARAYANAN P S 2200.00 194000041 547 PANAT HOUSE P O KARAYAVATTOM, VALAPAD THRISSUR KERALA 002809 GIREESH C T 2200.00 194000045 551 CHERIYA THOTTUNGAL H ICE ROAD VATAKARA-3 000000 003124 VENUGOPAL M R 2200.00 194000048 554 MOOTHEDATH (H) SAWMILL ROAD KOORVENCHERY THRISSUR GEETHADEVI M V 000000 RISHI M.V. 003292 SURENDARAN K K 2068.00 194000050 556 KOOTTALA (H) PO KOOKKENCHERY THRISSUR 000000 003442 POOKOOYA THANGAL 2068.00 194000053 559 MECHITHODATHIL HOUSE VELLORE PO POOKOTTOR MALAPPURAM 000000 003445 CHINNAN P P 2200.00 194000054 560 PARAVALLAPPIL HOUSE KUNNAMKULAM THRISSUR PETER P C 000000 001431 JITENDRA DATTA MISRA 6600.00 194000065 571 BHRATI AJAY TENAMENTS 5 VASTRAL RAOD WADODHAV PO AHMEDABAD 382415 IN30177410163576 Rukaiya Kirit Joshi 2695.00 194000081 587 303 Anand Shradhanand Road Vile Parle East Mumbai 400057 001012 SHARAVATHY C.H. 2200.00 194000088 594 W/O H.L.SITARAMAN, 15/2A,NAV MUNJAL NAGAR,HOUSING CO-OPERATIVE SOCIETY CHEMBUR, MUMBAI 400089 001424 BALARAMAN S N 11000.00 194000112 618 14 ESOOF LUBBAI ST TRIPLICANE MADRAS 600005 002473 GUNASEKARAN V 5500.00 194000114 620 NO.5/1324,18TH MAIN ROAD ANNA NAGAR WEST CHENNAI 600040 000697 AMALA S. -

List of Books

List of books SL. TITLE AUTHOR NO. PUBLISHER, PLACE, YEAR 1. Administration under the Basavaraja, K.R New Era Publications, Chalukayas of Kalyana Chennai 2. All the kings mana papers on Burton Steen New Era Publications, medieval South Indian history Chennai 3. Ancient Port of Arikamedu Vimala Begley Ecole Farucaise D’ Extreme- Orient Centre d. Historic et Archaeologic , Pondicherry 4. Art of Ancient India Susan L Huntington Weather hill Inc, New York 5. Blood weddings the Kananaga Suiderslu, R.M New Era publications, Christians of Kerala Chennai 6. Catalogue of Roman gold coins Satyamurthy, T Dept. of Archaeology, Government of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram 7. Catalogue of the coins of the Rapson, E.J Asian Educational Services, Andhra dynasty Madras 8. Chandogyoparisad Sankaranarayanan, S Adyar Library & Research Centre, Madras 9. Chola and Vijayanagara Naidu, P.N New Era publications, Chennai 10. Church history of Travancore Agur. C.M Asian Educational Services, Madras 11. Coins of Ancient India from Cunnigham, A Asian Educational Services, earliest time to 7th century AD Madras 12. Coins of Hyder Ali & Tippu Henderson, J.R Pioneer Book Service, Sultan Madras 13. Coins of India Brown, C.J Asian Educational Services, Chennai 14. Coins of Tipusultan Taylor, P Asian Educational Services, Madras 15. Conservation of Monuments in Seshadri, A.K Book India Publishing Co., India Delhi 16. Contribution to the study of Gerson Cunty, J Asian Educational Services, Indo Portuguese Numismatics Chennai 17. Dress and jewellery of women Uma Maheswari, C.S New Era publications, satavahara kakatiya Chennai 18. Economic conditions in Kuppuswamy, C.R Karnataka University, Karnataka (AD 973 to 1336) Dharward 19. -

„Rediscovering Jain Tradition in Wayanad‟

„REDISCOVERING JAIN TRADITION IN WAYANAD‟ MINOR RESEARCH PROJECT IN HISTORY SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION 2014-15 SASI C T (PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR) DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY GOVT COLLEGE, KALPETTA WAYANAD, KERALA - 673121 CONTENT Page No. 1. Declaration 2. Certificate 3. Acknowledgement 4. Preface, Objectives, Methodology 5. Literature Review i-iv 6. Chapter 1 1-5 7. Chapter 2 6-9 8. Chapter 3 10-12 9. Chapter 4 13-22 10 Chapter 5 23-27 11 Chapter 6 28-31 12 Chapter 7 32-34 13 Appendices 35-37 14 Table 38-41 15 Images 42-56 16 Select Bibliography 57-59 (A video graphic representation on the Jain temples is attached separately in a DVD) DECLARATION I, Sasi C.T, Principal Investigator, (Assistant Professor, Department Of History, Govt College, Kalpetta, Wayanad, Kerala) do here by declare that, this is a bona fide work by me, and that it was undertaken as a Minor Research Project funded by the University Grants Commission during the period 2014-15. Kalpetta 22/9/2015 SASI C T CERTIFICATE Govt College Kalpetta, Wayanad Kerala This is to certify that this Minor Research Project entitled „REDISCOVERING JAIN TRADITION IN WAYANAD‟, submitted to the University Grants Commission is a Minor research work carried out by Sasi C T, Assistant Professor, Department of History, Govt.College, Kalpetta. No part of this work has been submitted before. Kalpetta 22/9/2015 Principal ACKNOWLEDGEMENT For doing the Minor Research Project on „Rediscovering Jain traditions in Wayanad‟ I am owed much to the assistance of distinguished personalities and institutions. I am expressing my sincere thanks to the Librarians of different Libraries. -

GRO Details (Branches)

GRO Details (Branches) Region Name Type of Branch Branch / HPC Name GRO NAME ADDRESS CONTACT NUMBER Email SBI Life Insurance Company Ltd, Ahmedabad Primary Branch Ahmedabad 5 Mr. Ankit Panchal Office No. 303, Landmark Building, 100 Ft. Road, Anand 079-26934464 [email protected] Nagar, Satelite, Ahmedabad - 380015 SBI Life Insurance Company Ltd, 2Nd Floor, Office No.221 To 223, City Centre (Labha Ahmedabad Primary Branch Surendranagar Mr. Rakesh Zaveri 02752-226022 [email protected] Complex), Oppositem.P. Arts And Science College, Bus Stand, Surendranagar - 363001 SBI Life Insurance Company Ltd, 3Rd Floor, Office No. 302 Ahmedabad Primary Branch Anand Mr. Ajay Prasad And 303,Maruti Skand, Nr. Ioc Petrol Pump, Anand Vidhyanagar 02692-246270/1 [email protected] Road, Anand - 388001 SBI Life Insurance Company Ltd, Poonam Plaza, 3Rd Floor, Part 3 + Wing C, Near Ahmedabad Primary Branch Ahmedabad 4 Mr. Vikas Sharma 9033047072/3 [email protected] Swaminarayan Temple, Rambaug, Maninagar, Ahmedabad - 380028 Mr. Mahendra SBI Life Insurance Company Ltd, 301, 3Rd Floor, Shri Krishna Ahmedabad Primary Branch Jamnagar Avenue, Opp. Town Hall, Jamnagar District, Jamnagar - 361001 9033047968 / 69 [email protected] Dalsaniya SBI Life Insurance Company Ltd, 2Nd Floor, Tulsimilestone Ahmedabad Primary Branch Nadiad Mr. Anil Luhana Complex, Samir Hospital Compound, College Road, Nadia - 387001 0268 - 2526883/916 [email protected] SBI Life Insurance Co Ltd, 4Th Floor, 2/2, Pushpak Arcade, Ahmedabad Primary Branch Ahmedabad 6 Mr. Chirag Oza Near Holly Child School, Opp Hirawadi Brts Bus Stand, 079-22782220 [email protected] Thakkar Bapa Nagar, Ahmedabad - 382350 SBI Life Insurance Company Ltd, Ahmedabad Primary Branch Porbandar Mr. -

Sociology of Keralam (Sgy4b06)

SOCIOLOGY OF KERALAM (SGY4B06) STUDY MATERIAL CORE COURSE IV SEMESTER B.A. SOCIOLOGY (2019 Admission) UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION CALICUT UNIVERSITY P.O. MALAPPURAM - 673 635, KERALA 19456 School of Distance Education University of Calicut Study Material IV Semester B.A. SOCIOLOGY (2019 Admission) Core Course : SGY4B06 : SOCIOLOGY OF KERALAM Prepared by: Sri. JAWHAR. CT Assistant Professor, School of Distance Education, University Of Calicut. Scrutinised by: Smt. SHILUJAS. M Assistant Professor Department of Sociology Farook College, Kozhikode. DISCLAIMER "The author(s) shall be solely responsible for the content and views expressed in this book". Printed @ Calicut University Press SGY4B06: SOCIOLOGY OF KERALAM No. of Credits: 4, No. of hours/week: 4 Course outcomes 1. Recollect the social and cultural history of Kerala society 2. Explain the major social transformation in Kerala and its implications in present society 3. Analyses various socio cultural issues concerning Kerala society through sociological lens. CONTENTS Page Module No. I SOCIO-CULTURAL PROCESSES 1 - 29 AND ORIGIN OF KERALA SOCIETY 1.1 Life & culture in Sangam age, Chera- Chola period, traditions of Buddhism & Jainism, emergence of brahminic influence 1.2 Geographic specialities and culture of Malanadu, Edanadu, Theera Desam 1.3 Colonial influence, impact of colonial administration II SALIENT FEATURES OF SOCIAL 30 - 53 INSTITUTIONS IN KERALA 2.1 Forms and changes in marriage & family among Hindu, Christian, Page Module No. Muslims 2.2 Caste and Religion: -

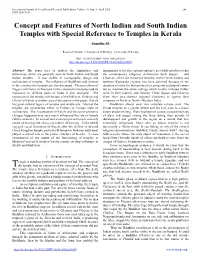

Concept and Features of North Indian and South Indian Temples with Special Reference to Temples in Kerala

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 10, Issue 4, April 2020 246 ISSN 2250-3153 Concept and Features of North Indian and South Indian Temples with Special Reference to Temples in Kerala Sumitha SS Research Scholar , Department of History , University of Kerala DOI: 10.29322/IJSRP.10.04.2020.p10029 http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.10.04.2020.p10029 Abstract- The paper tries to analyse the similarities and monuments to last for centuries and give us a fairly good idea what differences which are generally seen in North Indian and South the contemporary religious architecture built Stupas and Indian temples. It was visible in iconographs, design and Chaityas, which are in essence temples, in the Estern Andhra and architecture of temples. The influence of Buddhism and Jainism northern Karnataka regions, too have survived because of the in the construction temples are also discussed. The prevalence of adoption of stone for their protective casing and sculptured veneer Nagara and Versa architecture in the construction temples and its not to mention the stone railings which totally imitated timber expansion to differed parts of India is also analysed. The work in their journey and fixtures. These Stupas and Chaityas expansion of the temple architecture of the Pallavas, Pandyas and show their own distinct regional characters as against their Cholas to Kerala is another area of discussion in the paper. Kerala compeers in North an North –Western India. has great cultural legacy of temples and temple arts. Most of the Buddhism almost went into complete eclipse soon. The temples are constructed either in Pallava or Pandya style of Hindu temples to a greater extent and the Jain ones to a lesser architecture. -

Jainism in Haryana: an Archaeological Perspective

Jainism in Haryana: An Archaeological Perspective Vivek Dangi1 1. Department of History, All India Jat Heroes Memorial College, Rohtak, Haryana – 124 001, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 26 July 2017; Revised: 11 September 2017; Accepted: 04 November 2017 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 5 (2017): 300‐330 Abstract: The origin of Jainism is much earlier than Buddhism and most of the scholars agree that its antiquity goes back to Vedic times. Evidences of its existence are found in most of all the Indian states and Haryana was also an important centre of Jainism during hoary past. A large number of Jaina sculptures and other antiquities are occasionally found as chance discoveries from various archaeological sites in Haryana. The Jaina literature also refers to many important Jaina sites such as Agroha, Hansi, Rohtak etc. and many more place are yet to identify which are mentioned in ancient Jaina literature but so far as no attempt has been made to study the Jaina remains in Haryana in holistic perspective. Author of this paper have explored most of the known Jaina sites and provide a systematic documentation of recorded findings. Keywords: Tirthankara, Jaina, Haryana, Sculpture, Parsvanatha, Adinatha, Temple Introduction India has long been known as a very spiritual and religious part of the world. Religions are an integral part of all Indian traditions. Indian religions constitute a field of study that is of great importance to study of human culture overall. Religion in Haryana is a very complex phenomenon requiring careful study. However few studies thus far have been conducted on this aspect of Haryana culture. -

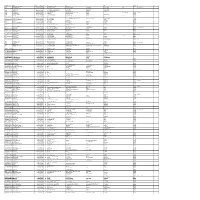

Mgl-Di420- List of Unpaid Shareholders As on 31.12

FOLIO-DEMAT ID NAME NETDIV DWNO MICR AD1 AD2 AD3 AD4 CITY PINCOD JH1 JH2 001221 DWARKA NATH ACHARYA 220000.00 204000027 5 JAG BANDHU BORAL LANE CALCUTTA 700007 000642 JNANAPRAKASH P.S. 2200.00 204000030 3 POZHEKKADAVIL HOUSE P.O.KARAYAVATTAM TRICHUR DIST. KERALA STATE 68056 MRS. LATHA M.V. 000691 BHARGAVI V.R. 2200.00 204000031 4 C/O K.C.VISHWAMBARAN,P.B.NO.63 ADV.KAYCEE & KAYCEE AYYANTHOLE TRICHUR DISTRICT KERALA STATE 001004 KARTHIKEYAN P.K. 2200.00 204000033 6 PANIKKASSERY HOUSE, THRIPRAYAR POST NATTIKA TRICHUR DIST. KERALA STATE 002769 RAMLATH V E 2200.00 204000037 10 ELLATHPARAMBIL HOUSE NATTIKA BEACH P O THRISSUR KERALA 003124 VENUGOPAL M R 2200.00 204000041 14 MOOTHEDATH (H) SAWMILL ROAD KOORVENCHERY THRISSUR GEETHADEVI M V 000000 RISHI M.V. 003292 SURENDARAN K K 2068.00 204000043 16 KOOTTALA (H) PO KOOKKENCHERY THRISSUR 000000 003442 POOKOOYA THANGAL 2068.00 204000045 18 MECHITHODATHIL HOUSE VELLORE PO POOKOTTOR MALAPPURAM 000000 003445 CHINNAN P P 2200.00 204000046 19 PARAVALLAPPIL HOUSE KUNNAMKULAM THRISSUR PETER P C 000000 IN30177410163576 Rukaiya Kirit Joshi 2695.00 204000064 37 303 Anand Shradhanand Road Vile Parle East Mumbai 400057 001012 SHARAVATHY C.H. 2200.00 204000065 38 W/O H.L.SITARAMAN, 15/2A,NAV MUNJAL NAGAR,HOUSING CO-OPERATIVE SOCIETY CHEMBUR, MUMBAI 400089 IN30028010510303 JAIN SANJAY KHEMCHAND 1815.00 204000068 41 185 RAVIWAR PETH SATARA 415002 IN30066910186257 B MURALIDHAR 1952.50 204000075 48 D NO 13-56/A KANKIPADU KRISHNA DIST 521151 000697 AMALA S. 4400.00 204000081 54 36 CAR STREET SOWRIPALAYAM COIMBATORE TAMILNADU 641028 001209 PANCHIKKAL NARAYANAN 22000.00 204000082 55 NANU BHAVAN KACHERIPARA KANNUR KERALA 670009 1202990005855228 SHEJI MATHEW KURIAKOSE 3135.00 204000083 56 658 Ozhukayil House P O Taliparamba Pushpagiri Dt Kannur 670141 003506 KAMALA K 2200.00 204000091 64 SRUTHY NIVAS ALACHANCODE CHITTUR COLLEGE P O CHITTUR PALAKKAD 678104 000637 MURALEEDHARAN T.R. -

Jainism from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Log in / create account article discussion edit this page history Jainism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "Jain" and "Jaina" redirect here. For other uses, see Jain (disambiguation) and Jaina (disambiguation). Jainism (pronounced /ˈdʒaɪnɪzəm/) is one of the oldest religions that navigation Jainism Main page originated in India. Jains believe that every soul is divine and has the Contents potential to achieve enlightenment or Moksha. Any soul which has Featured content conquered its own inner enemies and achieved the state of supreme Current events being is called jina (Conqueror or Victor). Jainism is the path to Random article achieve this state. Jainism is often referred to as Jain Dharma (जन ) or Shraman Dharma or the religion of Nirgantha or religion of search धम This article is part of a series on Jainism "Vratyas" by ancient texts. Jainism was revived by a lineage of 24 enlightened ascetics called Prayers and Vows Go Search tirthankaras[1] culminating with Parsva (9th century BCE) and Navakar Mantra · Ahimsa · interaction Mahavira (6th century BCE).[2][3][4][5][6] In the modern world, it is a Brahmacharya · Satya · Nirvana · Asteya · Aparigraha · Anekantavada About Wikipedia small but influential religious minority with as many as 4 million Community portal followers in India,[7] and successful growing immigrant communities Key concepts Recent changes Kevala Jñāna · Cosmology · in North America, Western Europe, the Far East, Australia and Samsara · Contact Wikipedia [8] elsewhere. Karma · Dharma · Mokṣa · Donate to Wikipedia Jains have sustained the ancient Shraman ( ) or ascetic religion Reincarnation · Navatattva Help मण and have significantly influenced other religious, ethical, political and Major figures toolbox economic spheres in India. -

Jaina Women and Their Identity As Reflected in the Early South Indian Inscriptions (C

Jaina Women and Their Identity as Reflected in the Early South Indian Inscriptions (c. 1st Century BCE ‐ 12th Century CE) M. S. Dhiraj1 1. Department of History, Pondicherry Central University, Pondicherry – 605 014, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 25 July 2019; Revised: 04 September 2019; Accepted: 09 October 2019 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 7 (2019): 450‐462 Abstract: Studies on the status of Women in historical context exclusively based on the analysis of epigraphical sources are few and far between, particularly in the case of Tamil, Kannada and Kerala regions of India. This paper will analyse the position and roles of Jain women as recorded in early and medieval inscriptions of the ancient Tamilakam including Karnataka and Kerala regions of Peninsular India. The study shows that Jain women in the records were largely Nuns and religious teachers who played a significant role in the spiritual scenario of the society and period under discussion. Records mention them as Kuratti, Kanti and Kavundi. They were described as carving out caverns and endowing them to other monks and Nuns of the same sect. They also constructed temples and basties. They made munificent land grants and other endowments to the Jain establishments called Pallis. They played the role of chief priestesses of the temples. In certain cases, they even organized monasteries exclusively for the Nuns and involved in large scale missionary and other spiritual activities. They provided public utilities for the common people. These inscriptions also attest to the role of the lay Jaina woman followers such as queens, princesses, family members of the subordinate rulers, dancing girls, etc. -

Jwalamalini Cult and Jainism in Kerala

Jwalamalini Cult and Jainism in Kerala K. Rajan1 1. Department of History, Government Victoria College, Palakkad, Kerala, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 30 June 2017; Revised: 02 August 2017; Accepted: 26 September 2017 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 5 (2017): 507‐513 Abstract: Jwalamalini is recognized as one of the Yakshi figures in Jaina iconography. Its origins are traced back to the early medieval period. Historians believe that the cult centred round Jwalamalini evolved in the Tamil lands. It represents the Tantric phase in south Indian Jainism. In Kerala, the most important example of a shrine dedicated to Jwalamalini is Palliyara Bhagavathy temple, near Vadakkenchery in Palakkad district. The four armed deity is now worshipped as a Bhagavathy. Archaeologists and historians have identified this shrine as one of the important remnants of Jaina heritage in Kerala. Located on the trade route linking Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu to Cochin, the shrine must have been prominent in the early medieval period. No inscription has been found in the temple. Keywords: Jwalamalini, Yakshi, Yapaniya Sect, Avarana‐Devata, Sasana Devata, Vahni Devata, Tantric Introduction Jawalamalini forms one of the Yakshis depicted in Jaina iconography. The present paper is focussed on tracing the origins of the cult of this deity in Kerala. Considered as `avarana‐devatas’ or `surrounding divinities’, Yakshis are said to be representing Shakti (Kramrisch 1976). The figures of Yakshas and Yakshis are found depicted in association with the Jaina Thirthankara images. The worship of Yaksas and Yakshis may be traced back to the pre‐Christian era. Buddhist sources indicate that Yakshi was considered as a malignant demon devoted to devouring children before the deity was abosorbed into it.