Crooked Lake: Emmet County

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Inland Waterway and Straits Area Water Trails Plan

Water Trail Plan Inland Waterway and Straits Area Cheboygan and Emmet Counties Funded by: Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce and the Michigan Coastal Management Program, Michigan Department of Environmental Quality with support from the Emmet County, Cheboygan County, Mackinaw City, and volunteers. June 2014 1 Inland Waterway and Straits Area Water Trail Plan Introduction The Inland Waterway is a 40 mile long historic water route that connects Lake Huron by way of Cheboygan, Indian River, Alanson, and Conway and with series of long portages at the headwaters to Petoskey State Park and Lake Michigan. A coastal route, part of the Huron Shores Blueways, connects the City of Cheboygan to Mackinaw City and the Straits of Mackinac. Like the interior water trails, the coastal waters have been used for transportation for thousands of years. The Inland Waterway has long been marketed as the motor boating paradise. Sitting along the banks of the Indian River on a summer afternoon and watching a steady stream of motored craft pass by, attests to the marketing success. There has never been a multi-community effort to organize and promote a paddle trail. Human-powered quiet water sports are among the fastest growing outdoor recreation activities. Combined with other active sports facilities such as the North Central State Trail, North Western State Trail and the North Country Trail, the water trail will bring visitors to the area, add to the quality of life for residents and enhance the rural-recreation sense of place. Furthermore, development of the water trail represents a regional, multi organization effort and will support economic development in the region of the state dependent upon recreational visitors. -

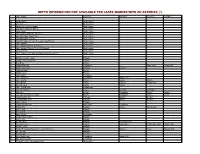

Depth Information Not Available for Lakes Marked with an Asterisk (*)

DEPTH INFORMATION NOT AVAILABLE FOR LAKES MARKED WITH AN ASTERISK (*) LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY GL Great Lakes Great Lakes GL Lake Erie Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Western Basin) Great Lakes GL Lake Huron Great Lakes GL Lake Huron (w West Lake Erie) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (Northeast) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (South) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (w Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes GL Lake Superior Great Lakes GL Lake Superior (w Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes AL Baldwin County Coast Baldwin AL Cedar Creek Reservoir Franklin AL Dog River * Mobile AL Goat Rock Lake * Chambers Lee Harris (GA) Troup (GA) AL Guntersville Lake Marshall Jackson AL Highland Lake * Blount AL Inland Lake * Blount AL Lake Gantt * Covington AL Lake Jackson * Covington Walton (FL) AL Lake Jordan Elmore Coosa Chilton AL Lake Martin Coosa Elmore Tallapoosa AL Lake Mitchell Chilton Coosa AL Lake Tuscaloosa Tuscaloosa AL Lake Wedowee Clay Cleburne Randolph AL Lay Lake Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Lay Lake and Mitchell Lake Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Lewis Smith Lake Cullman Walker Winston AL Lewis Smith Lake * Cullman Walker Winston AL Little Lagoon Baldwin AL Logan Martin Lake Saint Clair Talladega AL Mobile Bay Baldwin Mobile Washington AL Mud Creek * Franklin AL Ono Island Baldwin AL Open Pond * Covington AL Orange Beach East Baldwin AL Oyster Bay Baldwin AL Perdido Bay Baldwin Escambia (FL) AL Pickwick Lake Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL Shelby Lakes Baldwin AL Walter F. -

Inland Waterway

About the Navigating North Northern Michigan’s scenic Inland Waterway he closest communities to the Inland Waterway Tinclude Petoskey, Harbor Springs, Indian River and INLAND he first known improvement to the Inland Water- Cheboygan. Highways into the area include I-75 and Tway occurred in 1874 - the clearing of a sandbar at U.S. 31. The Web site, www.fishweb.com, has extensive the head of the Indian River. Prior to this time, the information about each of the waters along the route, lodging, boat service and rentals, boat ramps and related WATERWAY waterway was being used by Native Americans in canoes as a means of travel across the Northern end of the information. Lower Peninsula. During the lumbering era, the route was used extensively for transportation of products and people to the many resorts in the area. Since then, the 38 miles of connected lakes Inland Waterway has become one of the more popular and rivers through Emmet boat trips to be found anywhere in the country. and Cheboygan Counties Navigation notes: From Crooked Lake in Conway (Em- met County), the navigable waters flow toward Lake Hu- ron. Passing from lake to river, the water drops 18 inches at the Crooked River Lock. Through Alanson, past its quaint swing bridge, and north into Hay Lake (a marsh two miles long), the waters continue to flow northeast- erly. At Devil’s Elbow and at the Oxbow, the Crooked For information about Northern River lives up to its name. Here, on the forested banks, Front Cover 4” deer browse, herons gather and autumn creates a display Michigan, complimentary maps and more: of irresistible color. -

Village of Alanson / Littlefield Township Able of T Contents

Recreation Plan 2018-2022 Village of Alanson / Littlefield Township able of T Contents Village of Alanson/Littlefield Township Recreation Plan 2018-2022 Chapter Page Number 1.0 Introduction and Community Description Purpose of the Village of Alanson/ Littlefield Township Recreation Plan . 1 Community Description . 1 2.0 Administrative Structure Village Organization . 7 Past MDNR Grants and Other Funding Sources . 8 Township Organization . 9 Village and Township Cooperation . 10 Relationship with Other Agencies and Organizations . 10 3.0 Recreation Inventory Village of Alanson . 13 Littlefield Township . 15 Joint Village and Township . 15 Alanson-Littlefield Public Schools . 16 Alanson Beautification Center . 16 Oden Community Association . 17 Woodruff Park . 17 Street End Access to Crooked Lake . 17 Little Traverse Conservancy Nature Preserves . 19 Emmet County . 19 City of Petoskey Regional Parks . 21 Petoskey to Mackinaw City Rail Trail . 23 State of Michigan . 23 Private Recreational Facilities . 25 Americans with Disabilities Act Compliance . 25 Village of Alanson/Littlefield Township Recreation Plan 2018-2022 i Table of Contents (cont.) Chapter Page Number 4.0 Resource Inventory Water Resources . 27 Fish and Wildlife . 27 5.0 Description of the Planning Process . 31 6.0 Description of the Public Input Process . 33 7.0 Basis for Action / Goals and Objectives Recreation Trends . 37 National Planning Standards . 39 Acreage Standards . 39 Related Planning Initiatives . 44 Goals and Objectives . 45 8.0 Action Plan Capital Improvements Schedule . 51 Appendices A. Alanson/Littlefield Parks and Recreation Survey - Results Summary B. Notice of Availability of the Draft Plan for Public Review and Comment C. Notice for the Public Meeting D. Minutes of Public Meeting / Plan Adoption Meeting E. -

Pickerel and Crooked Lakes Aquatic Plant Surveys 2015

Pickerel and Crooked Lakes Aquatic Plant Surveys 2015 Pickerel Lake, Crooked Lake, Round Lake, and Crooked River Survey and report by Kevin L. Cronk, Daniel T.L. Myers, and Matthew L. Claucherty. Contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... 2 List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. 2 Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Background ................................................................................................................................. 7 Study Area ................................................................................................................................... 9 Pickerel and Crooked Lakes .................................................................................................... 9 Round Lake............................................................................................................................ 11 Crooked River (and Watershed) ............................................................................................ 12 Methods........................................................................................................................................ -

Crooked-Pickerel Lakes Shoreline Survey 2012 by Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council

Crooked-Pickerel Lakes Shoreline Survey 2012 By Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council Report written by: Kevin L. Cronk Monitoring and Research Coordinator i Table of Contents Page List of Tables and Figures iii Summary 1 Introduction 2 Background 2 Shoreline development impacts 3 Study Area 6 Methods 13 Field Survey Parameters 13 Data processing 16 Results 17 Discussion 21 Recommendations 24 Literature and Data Referenced 27 ii List of Tables Page Table 1. Crooked and Pickerel Lakes watershed land-cover statistics 9 Table 2. Categorization system for Cladophora density 14 Table 3. Cladophora density results 17 Table 4. Greenbelt rating results 18 Table 5. Shoreline alteration results 18 Table 6. Shoreline erosion results 19 Table 7. Shore survey statistics from Northern Michigan lakes. 22 List of Figures Page Figure 1. Crooked Lake, Pickerel Lake, and watershed 8 Figure 2. Secchi disc depth data from Crooked and Pickerel Lakes 10 Figure 3. Chlorophyll-a data from Crooked and Pickerel Lakes 10 Figure 4. Trophic status index data from Crooked and Pickerel Lakes 11 Figure 5. Phosphorus data from Crooked and Pickerel Lakes 12 iii SUMMARY Shoreline property management practices can negatively impact water quality and lake health. Nutrients are necessary to sustain a healthy aquatic ecosystem, but excess can adversely impact an aquatic ecosystem. Greenbelts provide many benefits to the lake ecosystem, which are lost when shoreline vegetation is removed. Erosion and shoreline alterations (seawalls, rip-rap, etc.) both have the potential to degrade water quality. During the late spring of 2012, the Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council conducted a comprehensive shoreline survey on Crooked and Pickerel Lakes to assess such shoreline conditions. -

Living with the Lakes! Liters X 0.26 = Gallons Area Square Kilometers X 0.4 = Square Miles

LivingLiving withwith thethe LakesLakes UnderstandingUnderstanding andand AdaptingAdapting toto GreatGreat LakesLakes WaterWater LevelLevel ChangesChanges MEASUREMENTS CONVERTER TABLE U.S. to Metric Length feet x .305 = meters miles x 1.6 = kilometers The Detroit District, established in 1841, is responsible for water Volume resource development in all of Michigan and the Great Lakes watersheds in cubic feet x 0.03 = cubic meters Minnesota, Wisconsin and Indiana. gallons x 3.8 = liters Area square miles x 2.6 = square kilometers Mass pounds x 0.45 = kilograms Metric to U.S. The Great Lakes Commission is an eight-state compact agency established in Length 1955 to promote the orderly, integrated and comprehensive development, use and conservation of the water resources of the Great Lakes basin. meters x 3.28 = feet kilometers x 0.6 = miles Volume cubic meters x 35.3 = cubic feet Order your copy of Living with the Lakes! liters x 0.26 = gallons Area square kilometers x 0.4 = square miles Mass kilograms x 2.2 = pounds This publication is a joint project of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Photo credits Detroit District, and the Great Lakes Commission. Cover: Michigan Travel Bureau; Page 3 (l. to r.): Michigan Travel Bureau, Michigan Travel Bureau, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (photo by David Editors Riecks); Page 4: Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (photo by David Riecks); Page 5: Roger Gauthier, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Detroit District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) (image by Lisa Jipping); Page 8: Michael J. Donahue, Julie Wagemakers and Tom Crane, Great Lakes Commission Michigan Travel Bureau; Page 9: National Park Service, Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore (photo by Richard Frear); Page 10 (t. -

Indian River & Burt Lake

SP 2017 (30) IWM Out 2 Final 6-6B_Layout 1 6/7/17 2:58 PM Page 1 FOUR LOCATIONS The THREE RIVERS of the Inland Waterway 2 2017 Northern Michigan’s Inland Waterway offers you a boating trip unlike any in the world. The approximately 42 mile trip takes you through three rivers and three lakes and surrounds you with some of the most beautiful scenery and captivating communities in Michigan. Once the route of Inland Waterway large Inland Route steamers, today’s boaters can enjoy many of the same sights that those a generation ago experienced. CHEBOYGAN Northern Michigan’s guide & map featuring marinas, accommodations, A voyage on the Inland Waterway can begin at the north end in boat rentals, restaurants, realtors, shopping and much more along the Inland Waterway. INDIAN RIVER Cheboygan, the south end in Conway, or anywhere along the 22 way. Boat launches are conveniently located at many places ONAWAY Cheboygan County Marina along the route. The trip can be made in a day or over a weekend, with the communities of Cheboygan, Topinabee, B OYNE CITY Aloha, Indian River, Alanson, Oden and Conway all located on Port of Cheboygan the water. Dining, lodging, supplies, and banking facilities can Continental Inn Seasonal Boat Slips be found in most of these communities. Numerous marinas The Nauti Inn Barstro Walstrom Marine SEASONAL BOAT SLIPS Citizens National Bank also dot the Inland Waterway where marine fuel, boat rentals, City on the Cheboygan River Cheboygan Area Visitors Bureau Hall and ships stores are situated for your convenience. The Boathouse Restaurant 517-898-3953 Carquest Auto Parts Whether you choose to make the Inland Waterway journey in a Best Western River Terrace Slip Rental includes Cheboygan River Lock & Dam day or make it a weekend, you will see a side of Northern 231-627-5688 parking, electric, water Michigan that cannot be seen along a highway or freeway. -

Michigan Department of Natural Resources Fisheries Division

ATUR F N AL O R T E N S E O U M R T C R E A S STATE OF MICHIGAN P E DNR D M ICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Number 34 August 2005 The Fish Community and Fishery of Crooked and Pickerel Lakes, Emmet County, Michigan with Emphasis on Walleyes and Northern Pike Patrick A. Hanchin, Richard D. Clark, Jr., Roger N. Lockwood, and Alanson Neal A. Godby, Jr.# Crooked River McPhee Creek Oden Fish Hatchery outflow # Oden Crooked Lake Pickerel Lake Channel Mud Creek � � � � Pickerel Lake 0 1 2 Mud Creek Miles Minnehaha Creek Cedar Creek www.michigan.gov/dnr/ FISHERIES DIVISION SPECIAL REPORT MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES FISHERIES DIVISION Fisheries Special Report 34 August 2005 The Fish Community and Fishery of Crooked and Pickerel Lakes, Emmet County, Michigan with Emphasis on Walleyes and Northern Pike Patrick A. Hanchin Michigan Department of Natural Resources Charlevoix Fisheries Research Station 96 Grant Street Charlevoix, Michigan 49721-0117 Richard D. Clark, Jr. and Roger N. Lockwood Neal A. Godby, Jr. School of Natural Resources and Environment Michigan Department of Natural Resources University of Michigan Gaylord Operations Service Center Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1084 1732 M-32 West Gaylord, Michigan 49735 MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES (DNR) MISSION STATEMENT “The Michigan Department of Natural Resources is committed to the conservation, protection, management, use and enjoyment of the State’s natural resources for current and future generations.” NATURAL RESOURCES COMMISSION (NRC) STATEMENT The Natural Resources Commission, as the governing body for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, provides a strategic framework for the DNR to effectively manage your resources. -

Great Lakes Lake Erie

4389 # of lakes LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY 99000 GL Great Lakes Great Lakes 99005 GL Lake Erie Great Lakes 99010 GL Lake Erie (Lake Erie Islands Region) Great Lakes 99015 GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo Region) Great Lakes 99020 GL Lake Erie (Put-In-Bay Area) Great Lakes 99025 GL Lake Erie (Western Basin Region) Great Lakes 99030 GL Lake Huron Great Lakes 99035 GL Lake Huron (With Lake Erie - Western Section) Great Lakes 99040 GL Lake Michigan (Northeastern Section) Great Lakes 99045 GL Lake Michigan (Southern Section) Great Lakes 99050 GL Lake Michigan (With Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes 99055 GL Lake Michigan (Lighthouses and Shipwrecks) Great Lakes 99060 GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes 99065 GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes 99066 GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes 99070 GL Lake Superior Great Lakes 99075 GL Lake Superior (With Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes 99080 GL Lake Superior (Lighthouses and Shipwrecks) Great Lakes 10000 AL Baldwin County Coast Baldwin 10005 AL Cedar Creek Reservoir Franklin 10010 AL Dog River * Mobile 10015 AL Goat Rock Lake * ChaMbers Lee Harris (GA) Troup (GA) 10020 AL Guntersville Lake Marshall Jackson 10025 AL Highland Lake * Blount 10030 AL Inland Lake * Blount 10035 AL Lake Gantt * Covington 10040 AL Lake Jackson * Covington Walton (FL) 10045 AL Lake Jordan ElMore Coosa Chilton 10050 AL Lake Martin Coosa ElMore Tallapoosa 10055 AL Lake Mitchell Chilton Coosa 10060 AL Lake Tuscaloosa Tuscaloosa 10065 AL Lake Wedowee Clay Cleburne Randolph 10070 AL Lay -

State of Michigan Department of Natural Resources

ATUR F N AL O R T E N S E O U M R T C R E A S STATE OF MICHIGAN P E DNR D M ICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Number 34 August 2005 The Fish Community and Fishery of Crooked and Pickerel Lakes, Emmet County, Michigan with Emphasis on Walleyes and Northern Pike Patrick A. Hanchin, Richard D. Clark, Jr., Roger N. Lockwood, and Alanson Neal A. Godby, Jr.# Crooked River McPhee Creek Oden Fish Hatchery outflow # Oden Crooked Lake Pickerel Lake Channel Mud Creek � � � � Pickerel Lake 0 1 2 Mud Creek Miles Minnehaha Creek Cedar Creek www.michigan.gov/dnr/ FISHERIES DIVISION SPECIAL REPORT MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES FISHERIES DIVISION Fisheries Special Report 34 August 2005 The Fish Community and Fishery of Crooked and Pickerel Lakes, Emmet County, Michigan with Emphasis on Walleyes and Northern Pike Patrick A. Hanchin Michigan Department of Natural Resources Charlevoix Fisheries Research Station 96 Grant Street Charlevoix, Michigan 49721-0117 Richard D. Clark, Jr. and Roger N. Lockwood Neal A. Godby, Jr. School of Natural Resources and Environment Michigan Department of Natural Resources University of Michigan Gaylord Operations Service Center Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1084 1732 M-32 West Gaylord, Michigan 49735 MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES (DNR) MISSION STATEMENT “The Michigan Department of Natural Resources is committed to the conservation, protection, management, use and enjoyment of the State’s natural resources for current and future generations.” NATURAL RESOURCES COMMISSION (NRC) STATEMENT The Natural Resources Commission, as the governing body for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, provides a strategic framework for the DNR to effectively manage your resources. -

Michigan's Inland Waterway

Courtesy of Michigan Living * July 1981 Excerpts from: Michigan’s Inland Waterway From Petoskey to Cheboygan By Carl Olson Recently, I asked someone if they had heard of the Inland Waterway Route and the response was, “Of course. It runs along the East Coast to Florida.” Wrong! It’s right here in Michigan. It runs from Petoskey to Cheboygan, passing through Crooked Lake, Crooked River, Burt Lake, Indian River, Mullett Lake and the Cheboygan River into Lake Huron. This water route has a recorded history going back well over 100 years and was first used by Indians in canoes as a shortcut from Lake Michigan to Lake Huron across the northern tip of the Lower Peninsula. The first improvement to the waterway came in 1874 when a large sandbar at the head of the Indian River was removed, making the route navigable to larger boats. During Michigan’s lumbering era, the system was used extensively for transporting forest products and supplying lumber camps which dotted the area. Around the turn of the century, small steam-powered excursion boats carried tourists and picnickers from the town of Conway on the western shore of Crooked Lake to the old resort hotel at Topinabee on Mullett Lake. If you stay to the northwest side of Mullett Lake you’ll soon pass Topinabee, the resort destination of the early steamers. Docks are available and, if you would like to see a bit more Michigan history, stop for a while and walk. Our trip across the lake, about 12 miles, was done at high speed, and we were concerned that our fuel wouldn’t last until Cheboygan.