United States V. Auernheimer and the Sixth Amendment Right to Be Tried in the District in Which the Alleged Crime Was Committed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

الجريمة اإللكرتونية يف املجتمع الخليجي وكيفية مواجهتها Cybercrimes in the Gulf Society and How to Tackle Them

مسابقة جائزة اﻷمير نايف بن عبدالعزيز للبحوث اﻷمنية لعام )2015م( الجريمة اﻹلكرتونية يف املجتمع الخليجي وكيفية مواجهتها Cybercrimes in the Gulf Society and How to Tackle Them إعـــــداد رامـــــــــــــي وحـــــــــــــيـد مـنـصــــــــــور باحـــــــث إســـتراتيجي في الشــــــئون اﻷمـــنـــية واﻻقتصـــــــــاد الســــــــياسـي -1- أ ت جملس التعاون لدول اخلليج العربية. اﻷمانة العامة 10 ج إ الجريمة اﻹلكترونية في المجتمع الخليجي وكيفية مواجهتها= cybercrimes in the Gulf:Society and how to tackle them إعداد رامي وحيد منصور ، البحرين . ـ الرياض : جملس التعاون لدول اخلليج العربية ، اﻷمانة العامة؛ 2016م. 286 ص ؛ 24 سم الرقم املوحد ملطبوعات اجمللس : 0531 / 091 / ح / ك/ 2016م. اجلرائم اﻹلكرتونية / / جرائم املعلومات / / شبكات احلواسيب / / القوانني واللوائح / / اجملتمع / مكافحة اجلرائم / / اجلرائم احلاسوبية / / دول جملس التعاون لدول اخلليج العربية. -2- قائمة املحتويات قائمة احملتويات .......................................................................................................... 3 قائمــة اﻷشــكال ........................................................................................................10 مقدمــة الباحــث ........................................................................................................15 مقدمة الدراســة .........................................................................................................21 الفصل التمهيدي )اﻹطار النظري للدراسة( موضوع الدراســة ...................................................................................................... 29 إشــكاليات الدراســة ................................................................................................ -

Darpa Starts Sleuthing out Disloyal Troops

UNCLASSIFIED (U) FBI Tampa Division CI Strategic Partnership Newsletter JANUARY 2012 (U) Administrative Note: This product reflects the views of the FBI- Tampa Division and has not been vetted by FBI Headquarters. (U) Handling notice: Although UNCLASSIFIED, this information is property of the FBI and may be distributed only to members of organizations receiving this bulletin, or to cleared defense contractors. Precautions should be taken to ensure this information is stored and/or destroyed in a manner that precludes unauthorized access. 10 JAN 2012 (U) The FBI Tampa Division Counterintelligence Strategic Partnership Newsletter provides a summary of previously reported US government press releases, publications, and news articles from wire services and news organizations relating to counterintelligence, cyber and terrorism threats. The information in this bulletin represents the views and opinions of the cited sources for each article, and the analyst comment is intended only to highlight items of interest to organizations in Florida. This bulletin is provided solely to inform our Domain partners of news items of interest, and does not represent FBI information. In the JANUARY 2012 Issue: Article Title Page NATIONAL SECURITY THREAT NEWS FROM GOVERNMENT AGENCIES: American Jihadist Terrorism: Combating a Complex Threat p. 2 Authorities Uncover Increasing Number of United States-Based Terror Plots p. 3 Chinese Counterfeit COTS Create Chaos For The DoD p. 4 DHS Releases Cyber Strategy Framework p. 6 COUNTERINTELLIGENCE/ECONOMIC ESPIONAGE THREAT ITEMS FROM THE PRESS: United States Homes In on China Spying p. 6 Opinion: China‟s Spies Are Catching Up p. 8 Canadian Politician‟s Chinese Crush Likely „Sexpionage,‟ Former Spies Say p. -

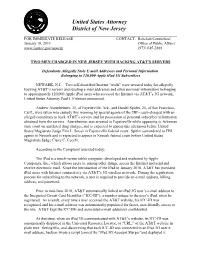

Two Men Charged in New Jersey with Hacking AT&T's Servers

United States Attorney District of New Jersey FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Rebekah Carmichael January 18, 2011 Office of Public Affairs www.justice.gov/usao/nj (973) 645-2888 TWO MEN CHARGED IN NEW JERSEY WITH HACKING AT&T’S SERVERS Defendants Allegedly Stole E-mail Addresses and Personal Information Belonging to 120,000 Apple iPad 3G Subscribers NEWARK, N.J. – Two self-described Internet “trolls” were arrested today for allegedly hacking AT&T’s servers and stealing e-mail addresses and other personal information belonging to approximately 120,000 Apple iPad users who accessed the Internet via AT&T’s 3G network, United States Attorney Paul J. Fishman announced. Andrew Auernheimer, 25, of Fayetteville, Ark., and Daniel Spitler, 26, of San Francisco, Calif., were taken into custody this morning by special agents of the FBI – each charged with an alleged conspiracy to hack AT&T’s servers and for possession of personal subscriber information obtained from the servers. Auernheimer was arrested in Fayetteville while appearing in Arkansas state court on unrelated drug charges, and is expected to appear this afternoon before United States Magistrate Judge Erin L. Setser in Fayetteville federal court. Spitler surrendered to FBI agents in Newark and is expected to appear in Newark federal court before United States Magistrate Judge Claire C. Cecchi. According to the Complaint unsealed today: The iPad is a touch-screen tablet computer, developed and marketed by Apple Computers, Inc., which allows users to, among other things, access the Internet and send and receive electronic mail. Since the introduction of the iPad in January 2010, AT&T has provided iPad users with Internet connectivity via AT&T’s 3G wireless network. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

No. 13-1816 in the UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for THE

Case: 13-1816 Document: 003111395511 Page: 1 Date Filed: 09/20/2013 No. 13-1816 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT _____________________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. ANDREW AUERNHEIMER, Appellant. Appeal from a Final Judgment in a Criminal Case of the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey (Crim. No. 11-470). Sat Below: Honorable Susan D. Wigenton, U.S.D.J. __________________________________________________________________ BRIEF FOR APPELLEE __________________________________________________________________ PAUL J. FISHMAN United States Attorney GLENN J. MORAMARCO Assistant U.S. Attorney Camden Federal Building 401 Market Street, Fourth Floor Camden, New Jersey 08101 (856) 968-4863 Case: 13-1816 Document: 003111395511 Page: 2 Date Filed: 09/20/2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Abbreviations ............................................. vi Table of Authorities .............................................. vii Statement of the Issues ............................................. 1 Statement of the Facts.............................................. 2 Statement of the Case ............................................. 14 Summary of Argument ............................................ 16 ARGUMENT I. THE GOVERNMENT PRESENTED SUFFICIENT EVIDENCE TO PERMIT THE JURY TO FIND THAT THE CONSPIRATORS’ ACCESSING OF AT&T’S SERVERS WAS UNAUTHORIZED. ......20 A. The Evidence Overwhelmingly Supported A Jury Finding That The Conspirators Improperly Accessed AT&T’s Computers By Impersonating Authorized Users............................24 -

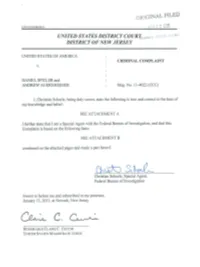

Orl GIN AL FILED

ORl GIN AL FILED LDVIZ120 10R0063 1 I '... ,', •I ".J ';Il0l..,1\1,1 lVU UNITED STATES DISTRICT COUR'fI.AIi<I> (.' :"Ce";' U.S DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY UNITED STATES OF AMERlCA CRIMINAL COMPLAINT V. DANIEL SPITLER and ANDREW AU ERN HEIMER Mag. No. 11-4022 (CCC) I, Christian Schorle, bei ng duly sworn, state the following is true and cOlTect to the best of my knowledge and belief. SEE ATTACHM E IT A I further state that I am a Special Agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigati on, and that this Complaint is based on the following facts: SEE ATTACHMENT B continued on the attached pages and made a part hereof. Christian Schor1e, Special Agent, Federal Bureau ofInvestigati on Sworn to before me and subscribed in my presence, January 13, 20 II , at Newark, ew Jersey c. HONORAB LE CLAtRE C. CECCHI UNITED STATES MAGISTRATE J UDGE ATTACHMENT A Countt (Conspiracy to Access a Computer without Authorization) From on or about June 2, 2010 through on or about June 11,2010, in the District of New Jersey, and elsewhere defendants DANIEL SPITLER and ANDREW AUERNHEIMER knowingly and intentionally conspired with each other and others to access a computer without authorization and to exceed authorized access, and thereby obtain information from a protected computer, namely the servers of AT&T, in furtherance of a criminal violation of the laws of the State of New Jersey, specifically, NJ.S.A. 2C:20-3I, contrary to Title 18, United States Code, Sections 1030(a)(2)(C) and I030(c)(2)(8)(ii), in violation of Title 18, United States Code, Section 371. -

A Target to the Heart of the First Amendment: Government Endorsement of Responsible Disclosure As Unconstitutional Kristin M

Northwestern Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property Volume 13 | Issue 2 Article 1 2015 A Target to the Heart of the First Amendment: Government Endorsement of Responsible Disclosure as Unconstitutional Kristin M. Bergman Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press Recommended Citation Kristin M. Bergman, A Target to the Heart of the First Amendment: Government Endorsement of Responsible Disclosure as Unconstitutional, 13 Nw. J. Tech. & Intell. Prop. 117 (2015). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njtip/vol13/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property by an authorized editor of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. NORTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF TECHNOLOGY AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY A Target to the Heart of the First Amendment: Government Endorsement of Responsible Disclosure as Unconstitutional Kristin M. Bergman May 2015 VOL. 13, NO. 2 Copyright 2015 by Northwestern University School of Law Volume 13, Number 2 (May 2015) Northwestern Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property A Target to the Heart of the First Amendment: Government Endorsement of Responsible Disclosure as Unconstitutional By Kristin M. Bergman* Brian Krebs, a former reporter for the Washington Post who is now known for his blog Krebs on Security, remained relatively unknown for most of his career. But in December 2013, Mr. Krebs found that hackers had exploited a data vulnerability in Target’s electronic-payment system, compromising millions of credit-card numbers that had been used to purchase goods from the second-largest discount retailer in the United States. -

Generation, Yes? Digital Rights Management and Licensing, from the Advent of the Web to the Ipad

Generation, Yes? Digital Rights Management and Licensing, from the Advent of the Web to the iPad by Reuven Ashtar A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Law Graduate Department of Law University of Toronto © Copyright by Reuven Ashtar (2010) ―Generation, Yes? Digital Rights Management and Licensing, from the Advent of the Web to the iPad.‖ A thesis submitted by Reuven Ashtar in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Law, Graduate Department of Law, University of Toronto, November 2010. ABTRACT The Article discusses digital-era courts‘ distortion of (para)copyright principles, deeming it borne of jumbled underlying legislation and a misplaced predilection for adopting licensing terms—even at the expense of recognized use exceptions. Common law evolutionary principles, it is shown, have been abandoned just when they are most needed: the ethereal rightsholder-user balance is increasingly disturbed, and the incipient ―generative consumer‖ is in thrall, not liberated. Finally, the Article puts forth a proposal for the reestablishment of the principle of substantially noninfringing use, showing it to be in the interests of innovation, democracy, and the greater public interest. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………1 II. SECURING PEACE FOR THE INDUSTRIES…………………………………….…3 A. The Walled Garden: “Paradise” Found B. Inventing, then Sharing, the World Wide Web C. Man Makes the Clothes? Jefferson, Clinton & the White Paper D. Brokering the DMCA—Negotiation, Hollywood-Style E. A Witches’ Brew F. DRM and the Nature of Control III. DMCA JURISPRUDENCE………………………………………………………….31 A. Sony, Innovation & Vigorous Commerce B. Early DMCA Jurisprudence: Drawing Lines in the Sand C. -

FBI Investigating AT&T Ipad Security Breach

FBI investigating AT&T iPad security breach 10 June 2010, By PETER SVENSSON , AP Technology Writer (AP) -- The FBI said Thursday that it is that plant malicious software on their computers. investigating a data breach at AT&T that exposed the e-mail addresses of more than 114,000 owners New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg's e-mail of the Apple iPad, including government officials. address was among those exposed, but the billionaire media mogul shrugged it off Thursday The agency said it is looking into "the potential and said he didn't understand the fuss. cyber threat" from the breach. "It shouldn't be pretty hard to figure out my e-mail AT&T Inc. said it has no comment. The Dallas- address," Bloomberg said, "and if you send me an based phone company acknowledged Wednesday e-mail and I don't want to read it, I don't open it. To that it had exposed the e-mail addresses through a me it wasn't that big of a deal." Web site, and had closed the breach. ©2010 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. The vulnerability only affected iPad users who This material may not be published, broadcast, signed up for AT&T's "3G" wireless Internet rewritten or redistributed. service. An AT&T Web site could be tricked into revealing an iPad owner's e-mail address when supplied with a code associated with their particular iPad. A hacker group that calls itself Goatse Security said it got the site to cough up more than 114,000 e-mail addresses by guessing which codes would be valid. -

1 1 in the United States District Court for The

1 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY 2 CRIMINAL ACTION2:11-cr-470-SDW 3 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, : TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS : 4 : T R I A L -vs- : 5 : ANDREW AUERNHEIMER, : Pages 1 - 85 6 : Defendant. : 7 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 8 Newark, New Jersey November 15, 2012 9 B E F O R E: HONORABLE SUSAN D. WIGENTON, 10 UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE and a Jury 11 A P P E A R A N C E S: 12 PAUL FISHMAN, ESQ., UNITED STATES ATTORNEY 13 BY: MICHAEL MARTINEZ, ESQ. ZACH INTRATER, ESQ., ESQ. 14 Attorneys for the Government 15 TOR EKELAND, P.C. BY: TOR EKELAND, ESQ. 16 MARK H. JAFFE, ESQ. Attorneys for the Defendant 17 18 ________________________________________________________ 19 Pursuant to Section 753 Title 28 United States Code, the following transcript is certified to be an accurate record as 20 taken stenographically in the above entitled proceedings. 21 S/Carmen Liloia 22 CARMEN LILOIA Official Court Reporter 23 (973) 477-9704 24 25 2 1 I N D E X 2 Witnesses Direct Cross Redirect Recross 3 For the Defense 4 ANDREW AUERNHEIMER 3 28 61 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 3 1 ANDREW AUERNHEIMER, Sworn. 2 DIRECT EXAMINATION BY DEFENSE2: 3 THE COURT: Very well. Good morning, Mr. Auernheimer. 4 You can proceed, Mr. Ekeland 5 MR. EKELAND: Thank you, your Honor. 6 Q Mr. Auernheimer, how old are you? 7 A Twenty-seven. 8 Q Mr. -

Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: the Story of Anonymous

hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy the many faces of anonymous Gabriella Coleman London • New York First published by Verso 2014 © Gabriella Coleman 2014 The partial or total reproduction of this publication, in electronic form or otherwise, is consented to for noncommercial purposes, provided that the original copyright notice and this notice are included and the publisher and the source are clearly acknowledged. Any reproduction or use of all or a portion of this publication in exchange for financial consideration of any kind is prohibited without permission in writing from the publisher. The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-583-9 eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-584-6 (US) eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-689-8 (UK) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the library of congress Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed in the US by Maple Press Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY I dedicate this book to the legions behind Anonymous— those who have donned the mask in the past, those who still dare to take a stand today, and those who will surely rise again in the future. -

The Most Dangerous Cyber Nightmares in Recent Years Halloween Is the Time of Year for Dressing Up, Watching Scary Movies, and Telling Hair-Raising Tales

The most dangerous cyber nightmares in recent years Halloween is the time of year for dressing up, watching scary movies, and telling hair-raising tales. Events in recent years have kept companies on high alert. Every day we are seeing an increase in cyberattacks carried out by organized hacker organizations. In a matter of seconds, these threats can destabilize large corporations, stealing large quantities of money and personal data, as well shake the very foundations of entire world powers. Have a look at some of the most terrifying attacks of recent years. 2010 2011 2012 Operation Aurora RSA SecurID Stratfor A series of cyberattacks carried out RSA suffered a security breach as a Publication and dissemination of worldwide, targeting 34 companies, result of a cyberattack that sought internal emails exchanged between including Google. The attack was details about its SecureID system. personnel of the private intelligence perpetrated by a group of Chinese espionage agency Stratfor, as well as hackers. PlayStation Network emails exchanged with clients of the firm. 77 million accounts were Australian Government compromised and blocked PS3 and DDoS attacks, carried out by the PlayStation Portable users from Linkedin online community Anonymous, accessing the service for 23 hours. The passwords of nearly 6.5 million against the Australian Government. user accounts were stolen by Russian cybercriminals. Operation Payback An attack coordinated jointly against opponents of Internet piracy. 2013 2014 Cyberattack in South Korea Celebrity photos Cyber networks of major South 500 private photographs of several Korean banks and television celebrities, mostly women, were networks were shut down in an placed on 4chan and subsequently alleged act of cyber warfare.