Guide to Art Lending Programs for Students in Institutions of Higher Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harvard University Graduate School of Design and Harvard Art Museums Announce Collaborative Exhibition the Divine Comedy

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Shannon Stecher Graduate School of Design 617-495-4784 [email protected] HARVARD UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF DESIGN AND HARVARD ART MUSEUMS ANNOUNCE COLLABORATIVE EXHIBITION The Divine Comedy consists of major installations by Olafur Eliasson, Tomás Saraceno, and Ai Weiwei that explore intersections of art, design, and the public domain CAMBRIDGE, MA (March 11, 2011)—The Harvard University Graduate School of Design and the Harvard Art Museums are pleased to announce an unprecedented three- part exhibition that addresses the converging domains of contemporary art and design practice. Entitled The Divine Comedy, this exhibition is comprised of major installations by internationally acclaimed artists Olafur Eliasson, Tomás Saraceno, and Ai Weiwei, and is on display March 21 through May 17, 2011, at the Graduate School of Design, the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, and the Northwest Science Building. “We are extremely excited to host these path-breaking artists and their explorations of how art and design can powerfully engage the public domain, an area of increasing focus at the Graduate School of Design,” said Mohsen Mostafavi, Dean, and Alexander and Victoria Wiley Professor of Design at the Graduate School of Design. The Divine Comedy borrows its title from Dante Alighieri’s epic medieval poem in which the author presents a vision of earthly existence as an allegorical journey through the realms of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven. Dante’s masterwork is widely considered to be the first poetic presentation in which scientific and philosophical themes were given central place. This exhibition explores the political dimensions of History (Weiwei), Mind (Eliasson), and Cosmos (Saraceno), and how these aspects of contemporary experience are being engaged by art and design speculation today. -

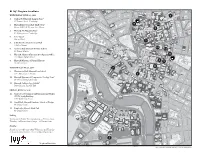

Ivy+ Program Locations

CUTLER AVE MILLER STREET PITMAN STREET CHILTON STREET AVON PL SPRING STREET HURLBUT ST LAUREL AV. KENNEDY MASSACHUSETTSAVENUE VASSAL LANE CYPRESS STREET TIERNEY HARRIS STREET BEACON STREET BEECH STREET DONNELL STREET EAST FRESH POND PARKWAY FAYERWEATHER STREET STREET GAR SACRAMENTO STREET DEN GARFIELD STREET 21 ST TRAYMORE GARDENS STREET BOWDOIN STREET OVERLAND STREET ST ARCADIA CONCORD AVE GRAY STREET EUSTIS STREET KELLEY STREET GRAY LINNAEAN STREET STANDISH STREET GRAY GARDENS MARTIN ST 20 ROBINSON STREET 1705 26 SOMERVILLE AVENUE YAWKEY WAY OXFORD ST GARDEN COURT SAVILLE STREET WEST Botanic Gardens 5A Sacramento Field BLEACHERY CT. BURLINGTON AVENUE WORTHINGTON STREET CRESCENT STREET KENT COURT VASSAL LANE Kittredge LAKEVIEW AVENUE WATERMAN RD LEXINGTON AVENUE Conway Playground HOLLY A 3 5 Kingsley Park MARTIN STREET FERNALD DRIVE Comstock SACRAMENTO PL Graham & V Parks WRIGHT STREET KENT STREET ENUE SACRAMENTO STREET B & M POPLAR RD HUTCHINSON MADISON STREET School AVON STREET HURON AVENUE RAILR FULLERTON STREET GARDEN ST Faculty Row PARK STREET GARDEN TER Maria L. OAD GURNEY STREET STREET Baldwin School Pforzheimer House ALLEN CT. DONNELL STREET STREET CARVER STREET Wolbach PROPERZI WAY VAN NESS STREET Tuchman WALKER STREET LAKE VIEW AVE Cabot 113 HUDSON Beckwith Circle FAYERWEATHER STREET Holmes R CT. BEAC HOWLAND ROYAL AVENUE MANASSAS AVENUE Moors 107 WENDELL STREET Hall TOWE HAWTHORNEBROOKLINE AVENUE PARK GRANVILLE ROAD Center for E Bingham ON STREET Landmark Center D Entry Astrophysics C 103 TYLER STREET 160 Harvard T WENDELL STREET HARRISON STREET Currier House Whitman GORHAM RESERVOIR STREET Briggs Hall MALCOLM ROAD Observatory STREET Dance Center SHEPARD STREE A Jordan North HURON AVE Gilbert Quadrangle RADCLIFFE B Daniels STREET QUADRANGLE STREET IVALOO STREET Athletic Center North Hall Harvard @ Trilogy St. -

SARA J. SCHECHNER David P. Wheatland Curator of The

SARA J. SCHECHNER David P. Wheatland Curator of the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments Lecturer on the History of Science Harvard University, Department of the History of Science Science Center 251c, 1 Oxford Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 (617) 496-9542 | [email protected] http://scholar.harvard.edu/saraschechner CONTENT Material Culture History of Astronomy EXPERTISE Science and Religion American Science Early Scientific Instruments Popular Culture and Science EDUCATION PhD (History of Science). Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 1988. AM (History of Science). Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 1982. MPhil (History and Philosophy of Science). Emmanuel College, Cambridge University, Cambridge, England, 1981. AB summa cum laude (History and Science, Physics). Harvard-Radcliffe, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 1979. AWARDS Paul Bunge Prize for the History of Scientific Instruments, Hans R. Jenemann-Stiftung, AND HONORS Gessellschaft Deutscher Chemiker (German Chemical Society) and Deutsche Bunsen-Gesellschaft für physikalische Chemie (German Bunsen Society for Physical Chemistry), 2019. LeRoy E. Doggett Prize for Historical Astronomy, American Astronomical Society, 2018. Telescopes-Mechanical/Other (second place), Stellafane Convention, for a quilt, “This is Stellafane!” 2018. Great Exhibitions Prize, British Society for the History of Science, for Body of Knowledge: A History of Anatomy (in 3 Parts), 2014. Dean’s Impact Award, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Harvard University, 2014. The Paul and Irene Hollister Lecturer on Glass, Bard Graduate Center, 2010. Telescopes-Mechanical/Special (first place), Stellafane Convention, for a historical quilt, “The Great 26-Inch Telescope at Foggy Bottom,” 2009. Joseph H. Hazen Education Prize, History of Science Society, 2008. First Place, International Design Awards 2007, for Time, Life, & Matter, 2007. -

Mary Schneider Enriquez Appointed As Harvard Art Museum's Houghton Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary

Mary Schneider Enriquez Appointed as Harvard Art Museum’s Houghton Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Cambridge, MA April 2, 2010 The Harvard Art Museum announces the appointment of Mary Schneider Enriquez as Houghton Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art in the museum’s Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, effective April 5, 2010. Schneider Enriquez has been Latin American art advisor to the Art Museum since 2002, working with the museum’s director and curatorial staff to identify collection and programmatic opportunities in Latin American art. She brings a long history of curatorial, academic, and administrative experience to this position, including undergraduate teaching, independent curatorial and advisory work for institutions across the U.S., art criticism, and fundraising. "I am pleased to welcome Mary to our staff," said Thomas W. Lentz, Elizabeth and John Moors Cabot Director of the Harvard Art Museum. “With her long and varied background in the art world, especially in Latin America, and as someone who already has an intimate knowledge of the Art Museum and Harvard University, she brings a distinct perspective to this position.” Currently visiting lecturer in fine arts at Brandeis University, Schneider Enriquez (Harvard A.B. ’81, A.M. ’87) is also completing her PhD in Harvard’s Department of History of Art and Architecture. She has served as a member of the Advisory Committee for Harvard’s David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies since 1995 and has been a member of the Board of Trustees at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, since 1999. She is also a member of the Harvard Art Museum’s World Visuality Committee, a group dedicated to addressing societies and their artistic traditions that have previously been underrepresented at Harvard. -

Research in the Fine Arts Library

Research in the Fine Arts Library The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Horrell, Jeffrey L. 2013. Research in the Fine Arts Library. Harvard Library Bulletin 23 (3), Fall 2012: 32. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42669024 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Research in the Fine Arts Library Jefrey L. Horrell Seneca Ray Stoddard, Te Adirondacks Illustrated (Glens Falls, N.Y., 1894). US 15461.22.24. n researching my dissertation (for a doctoral degree from Syracuse University) on the work, life, and context of the nineteenth-century IAdirondack writer and photographer Seneca Ray Stoddard, I was fortunate to have access to the full holdings of important journals in the Fine Arts Library that documented mid-to-late nineteenth-century photography and its reception. In addition, despite Harvard’s teaching the history of photography only infrequently up to the 1990s, I found that the overall strength of the photography holdings in the FAL was extraordinary. To follow leads and to make connections by browsing the open shelves were invaluable opportunities. To my amazement, afer not having found a single copy elsewhere, I discovered multiple copies of Stoddard’s guidebooks in the Widener Library collection. Even afer the fne arts books in Widener had been moved to the FAL, parts of these collections still spoke to one another in meaningful ways. -

Student Campus Map

STUDENT CAMPUS MAP 1 BRATTLE SQUARE HARVARD SQUARE 124 MOUNT AUBURN STREET (UNIVERSITY PLACE) BELFER CHARLES HOTEL Bell Hall 5 Land Lecture Hall 4 Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government (M-RCBG) 4 Updated August 2021 Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging (ODIB) 2 Starr Auditorium 2.5 Weil Town Hall L LITTAUER Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs 3 Campus Planning & Operations—Room Reservations G Dean of Students Office 1 IT Helpdesk G HKS QUAD Institute of Politics (IOP) 1 John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum 1 Library G | Mailroom G Master in Public Administration (MPA) Programs 1 Master in Public Policy (MPP) Program 1 Mid-Career Master in Public Administration (MC/MPA) Program 1 PhD Programs 1 OFER Office of Student Services 3 Student Government (KSSG) 3 Student Lounge 3 Student Public Service Collaborative (SPSC) 3 RUBENSTEIN JOHN F. Carr Center for Human Rights Policy 2 KENNEDY PARK Center for International Development (CID) G, 1, 3–5 Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy 4 Master in Public Administration/International Development (MPA/ID) Program 1 124 MT. AUBURN ST. | UNIVERSITY PLACE 1 BRATTLE SQUARE TAUBMAN Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation 2 Alumni Relations and Resource Development (ARRD) 3 Allison Dining Room (ADR) 5 Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy 2 Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs 3–5 Center for Public Leadership (CPL) 1–2 Executive Education 6 SUITE 165-SOUTH Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy 4 Enrollment Services (Offices of Admissions and Taubman Center for State and Local Government 3 Student Financial Services, Registrar) 1 Please wear your mask Women and Public Policy Program (WAPPP) 1 inside all buildings. -

BENEFITS ENROLLMENT GUIDE for Harvard Faculty, Administrative and Professional Staff, and Other Nonunion Staff

ENROLLMENT GUIDE 2021 BENEFITS Faculty & Nonunion Staff 2021 BENEFITS ENROLLMENT GUIDE For Harvard Faculty, Administrative and Professional Staff, and Other Nonunion Staff WHAT’S INSIDE HEALTH AND WELFARE • Medical and prescription drug ....................................................... 4 • Glossary ............................................................................................6 • Medical plan comparison tool ......................................................... 6 • Spending, savings, and reimbursement accounts ....................... 7 – Flexible Spending Accounts ....................................................... 7 – Health Savings Account ............................................................. 9 – Reimbursement Program .........................................................10 • Dental................................................................................................ 11 • Vision care ........................................................................................12 • Harvard University Health Services ..............................................13 DISABILITY AND LIFE • Short Term and Long Term Disability ...........................................14 • Life insurance ...................................................................................15 METLIFE LEGAL PLANS, IDENTITY THEFT PROTECTION, AND TUITION ASSISTANCE AND REIMBURSEMENT PROGRAMS .............................................16 RETIREMENT The employee benefit programs described • Tax-Deferred Annuity Plan .............................................................18 -

2017–2018 Arts and Humanities Initiative at Harvard Medical School Annual Report Contents About the Initiative

2017–2018 Arts and Humanities Initiative at Harvard Medical School Annual Report Contents About the Initiative .................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Mission .................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Goals ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Leadership ............................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Directors .............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Executive Committee .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Steering Committee ............................................................................................................................................................ 5 Accomplishments ................................................................................................................................................................... -

Student Handbook 2019—2020

Program in Neuroscience Student Handbook 2019—2020 Harvard University Program in Neuroscience Student Handbook Program in Neuroscience Department of Neurobiology Harvard Medical School Goldenson Building, Room 129 220 Longwood Avenue Boston, MA 02115 http://www.hms.harvard.edu/dms/neuroscience John Assad, Ph.D., Director David Ginty, Ph.D., Associate Director Karen Harmin, Administrator (617) 432-0912 Email: [email protected] August 2018 Overview of the Program in Neuroscience The Program in Neuroscience (“PiN”) is Harvard’s university-wide Ph.D. program in neuroscience. With over 130 research faculty members located at Harvard Medical School, Harvard’s Cambridge campus, and the Harvard-affiliated hospitals, it offers comprehensive training and outstanding research opportunities for graduate students. In the first year, students take the two mandatory core courses of the PiN curriculum: Quantitative Methods for Biologists (NB306QC), an intensive two-week boot camp in August that introduces students to statistics using the MATLAB programming language; and Discipline of Neuroscience (NB215), the year-long, flagship course of PiN that is designed to endow trainees with the broad, cross-discipline conceptual fluency required of neuroscientists. In consultation with faculty of the Student Advisory Committee, students may also choose to complete additional elective courses during their first year. PiN students must complete four quarters’ equivalence of electives (equaling two full semester courses), of which one quarter must be fulfilled by an advanced quantitative elective (e.g. NEUROBIO 308QC Thinking About Data: Statistics for the Life Sciences). While students are strongly encouraged to take advantage of neuroanatomy course offerings for their electives, neuroanatomy is not required. -

Course Guide 2Nd Edition

SECOND EDITION ABIGAIL ADAMS INSTITUTE Founded in 2014, AAI is a scholarly institute dedicated to providing supplementary humanistic education to the intellectual community of the Greater Boston area. We foster shared intellectual life by exploring questions of deep human concern that cut across the boundaries of academic disciplines. Throughout the year, we provide a range of programming for local college students and Cambridge young professionals including reading and discussion groups, workshops, lectures, conversations with faculty, intellectual retreats, and mentoring, while our summer seminars attract students and scholars from around the world. The name of the Institute honors the Massachusetts native Abigail Adams, whose capacious learning, judicious insight, and wise counsel shaped the founding and early development of the American nation. GENERAL INTRODUCTION This guide is meant to be useful to any Harvard College provides even a lifelong student the student who wants to make the best use of the opportunity to develop a taste for genuine College’s academic resources in the humanities. understanding. Your college years can be a time It highlights some of Harvard's truly of grounded and well-ordered intellectual outstanding courses and teachers. It also growth. We hope our Course Guide can be of provides a framework for thinking about what use to you in this endeavor. a humanistic education can look like in the twenty-first century, and it offers practical The Second Edition of this Guide has been advice on how to get such an education at a updated and expanded based on new course large modern research university like Harvard. offerings and student recommendations. -

Extracurriculars Stargazing If Weather Permits

New England REGIONAL SECTION Observatory Night lectures, followed by Extracurriculars stargazing if weather permits. SEAsONAL mUsIC fILm The Farmers’ Market at Harvard Sanders Theatre The Harvard Film Archive www.dining.harvard.edu/flp/ag_market. • October 21 at 8 p.m. http://hcl.harvard.edu/hfa; 617-495-4700 html. The Harvard Glee Club joins forces with Visit the website for complete listings. These outdoor markets emphasizing the Princeton Glee Club for a concert on • September 10-11 fresh, local foods and regional purveyors the night before the Harvard-Princeton World on a Wire by Rainer Werner Fass- run through October 25. football game. binder. A visionary science-fiction thriller RBORETUM; A In Cambridge: Tuesdays, noon-6 p.m. • October 28 at 8 p.m. made for German television in 1973. • NOLD Corner of Oxford and Kirkland streets, A “Montage Concert,” performed by the September 24-25 AR HE adjacent to Memorial Hall Harvard Monday Jazz Band, Harvard A Visit from Matt Porterfield. The Bal- T In Allston: Fridays, 3-7 p.m. Wind Ensemble, and the Harvard Uni timore native will discuss his work after K WEILER/ Corner of North Harvard Street and versity Band. screenings of Putty Hill and Hamilton, which c Western Avenue. feature amateur actors and capture subtle NAtURE AND sCIENCE aspects of youth and identity. thEAtER The Arnold Arboretum • September 26 IBRARY; JOSEPH FLA American Repertory Theater www.arboretum.harvard.edu; 617-384-5209 Radical Light: Alternative Film and Video L • www.americanrepertorytheater.org Opening October 29, with an artist’s recep- in the San Francisco Bay Area captures HAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY c 617-547-8300 (box office) tion on November 5, 1-3 p.m. -

NEWS RELEASE Harvard Exhibition of Visual Media in AIDS Activism Marks 20 Year Anniversary of the Formation of ACT up New York

NEWS RELEASE Harvard exhibition of visual media in AIDS activism marks 20 year anniversary of the formation of ACT UP New York Premiere of the ACT UP Oral History Project Cambridge, MA July 2, 2009 The Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts and the Harvard Art Museum present ACT UP New York: Activism, Art, and the AIDS Crisis, 1987–1993, an exhibition of over 70 politically-charged posters, stickers, and other visual media that emerged during a pivotal moment of AIDS activism in New York City. On view at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts October 15– Silence=Death Project, Silence=Death, 1986. December 23, 2009, the exhibition chronicles New York’s AIDS Coalition to Neon sign, 48 1/4 x 76 1/2 in. Copy of Unleash Power (ACT UP) through an examination of compelling graphics original from the collection of the New Museum, New York. Photo: Katya Kallsen. created by various artist collectives that populated the group. The exhibition also features the premiere of the ACT UP Oral History Project, a suite of over 100 video interviews with surviving members of ACT UP New York that offer a retrospective portal on a decisive moment in the history of the gay rights movement, 20th-century visual art, our nation’s discussion of universal healthcare, and the continuing HIV/AIDS epidemic. The exhibition opens just over 20 years after the formation of ACT UP and also marks the 40 year anniversary of the Stonewall riots, the defining event that marked the start of the gay rights movement in the United States.