A History of the Office of Usher at Sherborne School by W.B. Simms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Team Rector Writes

The Team Rector Writes... Dear Friends, When Bishop Nicholas visited the deaneries of the Diocese during Lent 2015 to develop our conversation around the vision RENEWING HOPE – PRAY, SERVE, GROW, he challenged us with three questions: What do you pray for? Whom do we serve? How will you grow? Questions that might at a first glance seem easy to answer: I want to encourage you to take time this Advent to look at those questions and allow yourselves to be more challenged than you expect! Advent and Christmas are seasons for the renewing of hope and I wonder whether we might try sharing our stories of hope with each other, as we seek to tell the greatest story of hope? At the start of diocesan meetings we now spend time sharing our stories of hope, talking about the things that have given us hope recently. First a candle is lit as the centre of the meeting – symbol of Christ’s presence in our midst; the Bible is read and studied; then people tell one another their stories. Simple but profound and challenging too! It is easy to be busy and preoccupied by the needs and demands of the day, especially in preparation for Christmas! But how life giving and holy it is to seek out and name those moments when hope has erupted. For some Christmas is unbounded joy and excitement, for others it is painful and troubling. However, it is the moment when we reflect on the truth that God became a human being; forever to experience our joys and sorrows alongside us. -

APRIL 2021 the Valley & Valence Parish Magazine for Winterborne St

Bluebells - by Alison Crawford APRIL 2021 The Valley & Valence Parish Magazine for Winterborne St. Martin • Winterbourne Steepleton • Winterbourne Abbas • Compton Valence V&V APR 21.indd 1 17/03/2021 08:38 V&V APR 21.indd 2 17/03/2021 08:38 THE APRIL 2021 & WE WANT YOUR PHOTOS! MAGAZINE Would you like the chance to see a photo taken by YOU VV on the front cover? The Valley & Valence Email your photo to me at: [email protected] Parish Magazine for make it relevant to the area in some way, let me know the Winterborne St. Martin title (or where it is) and put something like “photo for front Winterbourne Steepleton cover” as the subject of the email. Winterbourne Abbas One photo will be chosen each month to be on the front Compton Valence cover of this magazine - it could be yours! NEWS & ARTICLES FOR THE V&V PARISH MAGAZINE It would be much appreciated if copy is supplied electronically as a text doc. (Microsoft Word etc.) with any accompanying images as JPEG files to the address BELOW. ALL COPY MUST REACH ME BY 5pm on 15th (LATEST) OF THE PRECEDING MONTH in order to be included in that issue. ADVERTISING IN THE V&V PARISH MAGAZINE • Rates and Contact details Current rates & specifications enquiries, and advertisement copy for each month’s issue to: Graham Herbert, 1 Cowleaze, Martinstown, DT2 9TD Tel: 01305 889786 or email: [email protected] 3 V&V APR 21.indd 3 17/03/2021 08:38 Easter will be an even bigger event for us in the church this year, not so much in numbers because distancing restrictions will still be in place, but rather in joy and hope - the joy that we can be together again and the hope of what the future promises. -

Kim Sankey BA(Hons) Diparch Aadipcons RIBA Tel: 07742190490 | 01297 561045 Email: [email protected] Website

Kim Sankey BA(Hons) DipArch AADipCons RIBA Tel: 07742190490 | 01297 561045 Email: [email protected] Website: www.angel-architecture.co.uk Kim Sankey is a chartered Architect with more than 30 years’ experience spent wholly in the heritage sector. After graduating from Canterbury College of Art with a degree and diploma in Architecture and RIBA Part III, she achieved a further diploma in Building Conservation at the Architectural Association in London. Kim has worked both in the UK and overseas, including the conservation and reinstatement of fire damaged joinery at Uppark for the National Trust and repair and conservation of several war damaged buildings in Beirut. Latterly she was head of conservation for West Dorset District and Weymouth & Portland Borough Councils before starting her own chartered practice in 2014 covering the area of Dorset, Devon and Somerset. Kim inside Bridport Literary and Scientific Angel Architecture specialises in five areas – commercial clients, private clients, community Institute, for Bridport Area Development Trust projects, place making and heritage assessments. Kim has wide-ranging expertise including hands-on repair of historic buildings including mosaics, frescos, lime mortar and render. She also appears as expert witness in public inquiries in design matters and has been contract administrator for several complex historic building projects. She has been the author of many conservation area appraisals and has contributed heritage input to many neighbourhood plans. As well as running a busy practice Kim mentors undergraduates at the University of West of England and has applied to be on the conservation judging panel for the South West RIBA Regional Awards 2020. -

Water Situation Report Wessex Area

Monthly water situation report Wessex Area Summary – November 2020 Wessex received ‘normal’ rainfall in November at 84% LTA (71 mm). There were multiple bands of rain throughout November; the most notable event occurred on the 14 November, when 23% of the month’s rain fell. The last week of November was generally dry. The soil moisture deficit gradually decreased throughout November, ending the month on 7 mm, which is higher than the deficit this time last year, but lower than the LTA. When compared to the start of the month, groundwater levels at the end of November had increased at the majority of reporting sites. Rising groundwater levels in the Chalk supported the groundwater dominated rivers in the south, with the majority of south Wessex reporting sites experiencing ‘above normal’ monthly mean river flows, whilst the surface water dominated rivers in the north had largely ‘normal’ monthly mean flows. Daily mean flows generally peaked around 14-16 November in response to the main rainfall event. The dry end to November caused a recession in flows, with all bar two reporting sites ending the month with ‘normal’ daily mean flows. Total reservoir storage increased, with Wessex Water and Bristol Water ending November with 84% and 83%, respectively. Rainfall Wessex received 71 mm of rainfall in November (84% LTA), which is ‘normal’ for the time of year. All hydrological areas received ‘normal’ rainfall bar the Axe (69% LTA; 61 mm) and West Somerset Streams (71% LTA; 79 mm), which had ‘below normal’ rainfall. The highest rainfall accumulations (for the time of year) were generally in the east and south. -

![[DORSET.] 750 [POST OFFICE • Cerne](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4330/dorset-750-post-office-cerne-1474330.webp)

[DORSET.] 750 [POST OFFICE • Cerne

[DORSET.] 750 [POST OFFICE • Cerne. Totcombe and l\Iodbury:-Cattistock, Cerne Wimborne St. GiJes :-Hampreston, Wimborne St. Giles. Abba!o1, Compton Abbas, Godmanstoue, Hilfield, Nether Winfrith :-Coombe Keynes, East Lulworth, East Stoke, Cerne. Moreton Poxwell, Warmwell, Winfrith Newburgh, Woods- Cogdean :-Canford Magna, Charlton Marshall, Corfe ford. Mullen, Halllworthy, Kinson or Kin~stone, Longfleet, WJke Regis and Elwellliberty :-Wyke Regis. Lytchett Matl'avers, LJtchett l\1inster, Parkstone, 8tur- Yetminster :- Batcomhe, Chetnole, Clifton May bank, minster Marshall. Leigh, Melbury Bllbb, Melbury OSlllond, Yetminster. Coombs Ditch :-Anderilon, Blandford St. Mary, Bland- Bridport borough :-Bridport. ford Forum, Bloxworth, Winterborne Clenstone, Winter- Dorchester borough :-AlI Saints (Dorchester), Holy borne Thomson, Winterborne Whitechurch. Trinity (Dorchester), St. Peter (Dorchester). Corfe Castle :-Corfe Castle. Lyme Regis boroug-h. Cranborne :-Ashmore, Bellehalwell.Cranborne, Edmons- Poole Town and County: -St. James (Poole). ham. Farnham Tollard, Pentridge, Shillingstone or Shilling Shaftesbury borough :-Holy Trinity (Shaftesbury), St. Okeford, Tarrant Gunville, Tarrant Rushton, Turnwortb, James (Shaftesbury), St. Peter (Shaftesbury). West Parley, Witchampton. Wareham borough :-Lady St. Mary (Wareham), St. Culliford Tree:-Broadway, Buckland Ripers, Osmington, Martin (Wareham), The Holy Trinity (Wareham). Radipole, West Chickerell, West Knightoll, West Stafford, Weymouth borough :-Melcombe Regis, Weymouth. Whitcom be, Winterbourne Came, Winterbourne Herring- The old Dorset County Pauper Lunatic Asylum, is situated stone, Winterbourne Moncktoll. at Forston, 2~ miles north-west from Charminster: it fiu- Dewlish liberty :-Dewlish. nishes accommodation for 150 patients: it was formerly the E!!gerton :-Askerswell, Hook, Long Bredy, Poorstock, seat of the late Fl'ancis John Browne, who ~ave it to the Winterbourne Abbas, Wraxall. county for this purpose, and was opened in 1832; it has been FOl'dil1~toll' liberty :-Fordington, Frampton, Hermitage. -

Dorset Bird Report 2008

Dorset Bird Report 2008 Dorset Bird Club Blank Page Dorset Bird Report 2008 Published August 2010 © 2010 Dorset Bird Club 2008 Dorset Bird Report 1 We offer Tailor-made birding & wildlife tours Specialists in out-of-print Themed birding and wildlife walks NATURAL HISTORY BOOKS Local guides for groups Books bought & sold Illustrated wildlife talks UK & overseas wildlife tours and guides Log on to our website for a full stock list or contact us for a copy Check out our website or contact us of our latest catalogue for further details www.callunabooks.co.uk www.dorsetbirdingandwildlife.co.uk [email protected] [email protected] Neil Gartshore, Moor Edge, 2 Bere Road, Wareham, Dorset, BH20 4DD 01929 552560 What next for Britain’s birds? • Buzzards spread, Willow Tits disappear... • What about House Martins... or winter thrushes? • Who will hit the headlines in the first National Atlas since 1991? Be prepared, get involved! • Survey work starts in November 2007 • Over £1 Million needed for this 5-year project ? Visit www.bto.org/atlases to find out more! The 2007-2011 Atlas is a joint BTO/BWI/SOC Project Registered Charity No. 216652 House Martin by M S Wood 2 Dorset Bird Report 2008 DORSET BIRD REPORT 2008 CONTENTS Report Production Team . .5 Current Committee of the Dorset Bird Club . .5 Notes for Contributors . 6-7 Review and Highlights of 2008 . 8-13 The Dorset List . 14-18 Systematic List for 2008 . 20-183 Notes to Systematic List . 19 Escapes . 184-185 Pending and Requested Records . 186-187 Dorset Bird Ringing Summary and Totals for 2008 . -

Beacon Ward Beaminster Ward

As at 21 June 2019 For 2 May 2019 Elections Electorate Postal No. No. Percentage Polling District Parish Parliamentary Voters assigned voted at Turnout Comments and suggestions Polling Station Code and Name (Parish Ward) Constituency to station station Initial Consultation ARO Comments received ARO comments and proposals BEACON WARD Ashmore Village Hall, Ashmore BEC1 - Ashmore Ashmore North Dorset 159 23 134 43 32.1% Current arrangements adequate – no changes proposed Melbury Abbas and Cann Village BEC2 - Cann Cann North Dorset 433 102 539 150 27.8% Current arrangements adequate – no changes proposed Hall, Melbury Abbas BEC13 - Melbury Melbury Abbas North Dorset 253 46 Abbas Fontmell Magna Village Hall, BEC3 - Compton Compton Abbas North Dorset 182 30 812 318 39.2% Current arrangements adequate – no Fontmell Magna Abbas changes proposed BEC4 - East East Orchard North Dorset 118 32 Orchard BEC6 - Fontmell Fontmell Magna North Dorset 595 86 Magna BEC12 - Margaret Margaret Marsh North Dorset 31 8 Marsh BEC17 - West West Orchard North Dorset 59 6 Orchard East Stour Village Hall, Back Street, BEC5 - Fifehead Fifehead Magdalen North Dorset 86 14 76 21 27.6% This building is also used for Gillingham Current arrangements adequate – no East Stour Magdalen ward changes proposed Manston Village Hall, Manston BEC7 - Hammoon Hammoon North Dorset 37 3 165 53 32.1% Current arrangements adequate – no changes proposed BEC11 - Manston Manston North Dorset 165 34 Shroton Village Hall, Main Street, BEC8 - Iwerne Iwerne Courtney North Dorset 345 56 281 119 -

Axminster X51 Weymouth

Dorchester - Poundbury - Bridport - Lyme Regis - Axminster X51 Weymouth - Portesham - West Bay - Bridport - Lyme Regis - Axminster X52 X53 aslo showing school service A3 between Bridport and Woodroffe School, and the open top X52 between Weymouth and Bridport Monday to Friday Service Number X53 A3 X53 X51 X52 X53 X51 X52 X53 X51 X52 X53 X51 X51 X52 X53 X53 X51 Sch NSch Sch NSch Sch Weymouth King's Statue .... .... 0700 .... 0815 .... 0913 0930 1025 1113 1125 1225 1313 1313 1325 1425 1425 1513 Fiveways .... .... 0706 .... 0824 .... .... 0941 1036 .... 1136 1236 .... .... 1336 1436 1436 .... Chickerell Meadow Close .... .... 0711 .... 0830 .... .... 0948 1043 .... 1143 1243 .... .... 1343 1443 1443 .... Portesham Kings Arms .... .... 0718 .... 0839 .... .... 0958 1053 .... 1153 1253 .... .... 1353 1453 1453 .... Abbotsbury Ilchester Arms .... .... 0723 .... 0844 .... .... 1003 1058 .... 1158 1258 .... .... 1358 1458 1458 .... Burton Bradstock, Three Horseshoes .... .... 0734 .... 0857 .... .... 1018 1113 .... 1213 1313 .... .... 1413 1513 1513 .... West Bay George Hotel .... .... 0740 .... 0904 .... .... 1026 1121 .... 1221 1321 .... .... 1421 1521 1521 .... Dorchester Road, Morrisons .... .... .... .... .... .... 0922 .... .... 1122 .... .... 1322 1322 .... .... .... 1522 Dorchester South Station .... .... .... .... .... .... 0937 .... .... 1137 .... .... 1337 1337 .... .... .... 1537 Dorchester South Station .... .... .... 0805 .... .... 0942 .... .... 1142 .... .... 1342 1342 .... .... .... 1542 Dorchester Trinity Street .... .... ... -

STATEMENT of PERSONS NOMINATED Date of Election : Thursday 7 May 2015

West Dorset District Council Authority Area - Parish & Town Councils STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED Date of Election : Thursday 7 May 2015 1. The name, description (if any) and address of each candidate, together with the names of proposer and seconder are show below for each Electoral Area (Parish or Town Council) 2. Where there are more validly nominated candidates for seats there were will be a poll between the hours of 7am to 10pm on Thursday 7 May 2015. 3. Any candidate against whom an entry in the last column (invalid) is made, is no longer standing at this election 4. Where contested this poll is taken together with elections to the West Dorset District Council and the Parliamentary Constituencies of South and West Dorset Abbotsbury Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer and Seconder Invalid DONNELLY 13 West Street, Abbotsbury, Weymouth, Company Director Arnold Patricia T, Cartlidge Arthur Kevin Edward Patrick Dorset, DT3 4JT FORD 11 West Street, Abbotsbury, Weymouth, Wood David J, Hutchings Donald P Henry Samuel Dorset, DT3 4JT ROPER Swan Inn, Abbotsbury, Weymouth, Dorset, Meaker David, Peach Jason Graham Donald William DT3 4JL STEVENS 5 Rodden Row, Abbotsbury, Weymouth, Wenham Gordon C.B., Edwardes Leon T.J. David Kenneth Dorset, DT3 4JL Allington Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer and Seconder Invalid BEER 13 Fulbrooks Lane, Bridport, Dorset, Independent Trott Deanna D, Trott Kevin M Anne-Marie DT6 5DW BOWDITCH 13 Court Orchard Road, Bridport, Dorset, Smith Carol A, Smith Timothy P Paul George DT6 5EY GAY 83 Alexandra Rd, Bridport, Dorset, Huxter Wendy M, Huxter Michael J Yes Ian Barry DT6 5AH LATHEY 83 Orchard Crescent, Bridport, Dorset, Thomas Barry N, Thomas Antoinette Y Philip John DT6 5HA WRIGHTON 72 Cherry Tree, Allington, Bridport, Dorset, Smith Timothy P, Smith Carol A Marion Adele DT6 5HQ Alton Pancras Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer and Seconder Invalid CLIFTON The Old Post Office, Alton Pancras, Cowley William T, Dangerfield Sarah C.C. -

Catchment Report 2015

Catchment report 2015 www.wessexwater.co.uk Introduction Welcome to the first edition of our annual catchment report. In the past water authorities organised themselves according to river catchments and often controlled land use around water sources to prevent contamination of groundwater. However, after privatisation the focus shifted to upgrading water and sewage treatment infrastructure to provide greater guarantees that drinking water and effluent standards would be met within short timescales. While major improvements were made to the quality of our drinking water and treated effluent, they came at a high price in terms of capital and operational costs such as additional treatment chemicals and an increased carbon footprint, due to the energy used. More recently, there has been an upsurge in interest in catchment management as a less resource-intensive way to protect groundwater, streams and rivers. Since 2005 we have been carrying out catchment work in cooperation with farmers to optimise nutrient and pesticide inputs to land. This often means dealing with the causes of problems by looking at land use, management practices and even the behaviour of individuals. Addressing the issue at source is much more sustainable than investing in additional water treatment that is expensive to build and operate and leaves the problem in the environment. At the same time we have been amassing data on the condition of the rivers and estuaries in our region to ensure that any subsequent investment is proportional and based on solid evidence. We have also been working on different ways to engage with the public and influence behaviour to help protect water supplies and sewers and, in turn, the water environment. -

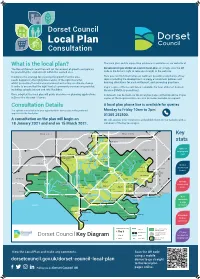

What Is the Local Plan? Consultation Details Dorset Council Key Diagram

What is the local plan? The local plan and its supporting evidence is available on our website at The Dorset Council Local Plan will set the amount of growth and policies dorsetcouncil.gov.uk/dorset-council-local-plan, or simply scan the QR for protecting the environment within the council area. code in the bottom right to take you straight to the website. It outlines the strategy for ensuring the growth that the area Here you can find information on webinars providing summaries of key needs happens in the right places and is of the right character, topics including the development strategy, environment policies and whilst protecting the natural environment and acting on climate change. housing allocations for each settlement, and answering questions. It seeks to ensure that the right level of community services are provided, Paper copies of the Local Plan are available for loan at Dorset Council including schools, leisure and retail facilities. libraries (COVID-19 permitting) . Once adopted, the local plan will guide decisions on planning applications Comments can be made on the local plan pages at the link above. Paper in Dorset for the next 15 years. copies of the response form can also be made available on request. Consultation Details A local plan phone line is available for queries The options consultation is your opportunity to have a say on the preferred Monday to Friday 10am to 2pm: approach to the local plan. 01305 252500. A consultation on the plan will begin on We will analyse your comments and publish them on our website with a 18 January 2021 and end on 15 March 2021. -

Sponsored Cycle Ride

DHCT – RIDE+STRIDE – LIST OF CHURCHES - Saturday 14th September 2019 - 10.00am to 6.00pm To help you locate churches and plan your route, the number beside each church indicates the (CofE) Deanery in which it is situated. Don’t forget that this list is also available on the website by Postcode, Location and Deanery. 1- Lyme Bay 2 - Dorchester 3 - Weymouth 4 - Sherborne 5 – Purbeck 6 - Milton & Blandford 7 - Wimborne 8 - Blackmore Vale 9 – Poole & N B’mouth 10- Christchurch 3 Abbotsbury 4 Castleton, Sherborne Old Church 5 Affpuddle 1 Catherston Leweston Holy Trinity 7 Alderholt 4 Cattistock 4 Folke 1 Allington 4 Caundle Marsh 6 Fontmell Magna 6 Almer 2 Cerne Abbas 2 Fordington 2 Athelhampton Orthodox 7 Chalbury 2 Frampton 2 Alton Pancras 5 Chaldon Herring (East Chaldon) 4 Frome St Quinton 5 Arne 6 Charlton Marshall 4 Frome Vauchurch 6 Ashmore 2 Charminster 8 Gillingham 1 Askerswell 1 Charmouth 8 Gillingham Roman Catholic 4 Batcombe 2 Cheselbourne 4 Glanvilles Wootton 1 Beaminster 4 Chetnole 2 Godmanstone 4 Beer Hackett 6 Chettle 6 Gussage All Saints 8 Belchalwell 3 Chickerell 6 Gussage St Michael 5 Bere Regis 1 Chideock 6 Gussage St Andrew 1 Bettiscombe 1 Chideock St Ignatius (RC) 4 Halstock 3 Bincombe 8 Child Okeford 8 Hammoon 4 Bishops Caundle 1 Chilcombe 7 Hampreston 1 Blackdown 4 Chilfrome 9 Hamworthy 6 Blandford Forum 10 Christchurch Priory 1 Hawkchurch Roman Catholic 5 Church Knowle 8 Hazelbury Bryan Methodist 7 Colehill 9 Heatherlands St Peter & St Paul 8 Compton Abbas 4 Hermitage United Reformed 2 Compton Valence 10 Highcliffe