Managing Tithes in the Late Middle Ages*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Castle Eden Colliery

DIRECTORY. 461 MUGGLESWICK. [DURHAM.j • • the churcll, and commanding extensive sea views; it is the Iof the above reverend g-entleman; the style is Gothic. On property of F. A. Milbanke, Esq., and at present occupied the right of the altar is the small handsome chapel of the by Thomas Moon, Esq. I Virgin Mary and Child; over the altar is a painting of the CASTLE EDEN COLLIERY is a hamlet and village in Crncifixion, and on each side are (in fresco) the Nativity, this township, cunsisting of several rows of workmen's cot- Agony in the Garden, and the Resurrection. F. A. Millbank, tages, occupied by the colliers engaged in the extensive Esq., is lord of the manor, and the principal landowners are Castle Eden Colliery, situated in the adjoining township. Lord Howden, Rowland Burdon, Esq., and the Rev. Thos. In this village is a station of the Sunderland and Hartlepool Augustine Slater, with many smaller proprietors. The railway, 6 miles from the latter town, and 11~ from Ferry- acreage is about 1,987 and, the population, in 1851, was hill. Here are chapels for Wesleyans and Primitive Metho- 1,067. dists, and a g'ood National school; the area of the township ROAD RInGE is a villag·e. is 2,456 acres, and the population, in 1851, was 1,495. 'l'he SHERATON and HULAM are two small townships in the landowners are F. A. IHilbanke, Esq., the representatives of parish of Monk Hesledell; the former is 2~ miles and the the late 1\1:rs. Burdon, R. -

Handlist 13 – Grave Plans

Durham County Record Office County Hall Durham DH1 5UL Telephone: 03000 267619 Email: [email protected] Website: www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk Handlist 13 – Grave Plans Issue no. 6 July 2020 Introduction This leaflet explains some of the problems surrounding attempts to find burial locations, and lists those useful grave plans which are available at Durham County Record Office. In order to find the location of a grave you will first need to find which cemetery or churchyard a person is buried in, perhaps by looking in burial registers, and then look for the grave location using grave registers and grave plans. To complement our lists of churchyard burial records (see below) we have published a book, Cemeteries in County Durham, which lists civil cemeteries in County Durham and shows where records for these are available. Appendices to this book list non-conformist cemeteries and churchyard extensions. Please contact us to buy a copy. Parish burial registers Church of England burial registers generally give a date of burial, the name of the person and sometimes an address and age (for more details please see information about Parish Registers in the Family History section of our website). These registers are available to be viewed in the Record Office on microfilm. Burial register entries occasionally give references to burial grounds or grave plot locations in a marginal note. For details on coverage of parish registers please see our Parish Register Database and our Parish Registers Handlist (in the Information Leaflets section). While most burial registers are for Church of England graveyards there are some non-conformist burial grounds which have registers too (please see appendix 3 of our Cemeteries book, and our Non-conformist Register Handlist). -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

(& Stanwick St. John & Caldwell) Ampleforth Appleton Wiske Ar

Monumental Inscriptions. The Centre for Local Studies, at Darlington Library has an extensive collection of Monumental Inscriptions compiled by the Cleveland, South Durham and North Yorkshire Family History Society. Acklam (Middlesbrough) Ainderby Steeple Aislaby Aldborough (& Stanwick St. John & Caldwell) Ampleforth Appleton Wiske Arkendale Arkengarthdale Arkletown, Wesleyan Chapel & St. Mary, Langthwaite Arkengarthdale (Yrks) Askrigg Auckland Auckland, St Andrew Auckland, St Andrew Extension Auckland, St Andrew (fiche) Aucklandshire and Weardale (Hearth Tax 1666) Aycliffe (see also School Aycliffe & U429AYCb LHOS Stephenson Way) Aysgarth Bagby Bainbridge Bainbridge and Carperby Baldersby Barnard Castle (St Mary/Roman Catholic/Victoria Road) Barningham Barton Bedale Bellerby Billingham Bilsdale Bilsdale Midcable Birkby Bishop Middleham Bishopton Boltby Bolton on Swale Boosbeck Bowes Bransdale (& Carlton) Brignall 13/07/2015 Brompton (near Northallerton) Brompton Cemetery (near Northallerton) Brotton Burneston Carlbury Carlton Miniott Carton in Cleveland Castle Eden Castleton Catterick Cleasby Coatham Cockfield Cold Kirby Commondale Coniscliffe (Carlbury) Carlbury (see Coniscliffe) Cornforth Cotherstone Coverham Cowesby Cowton (See East Cowton/South Cowton) Croxdale, St Bartholomew Coxwold Crakehall Crathorne Croft on Tees Cundall Dalby Dalton in Topcliffe Danby Danby Wiske Darlington Deaf Hill Deighton Denton Dinsdale Dishforth Downholme Easby Easington East Cowton (See Cowton) East Harsley (East) Loftus East Rounton East Witton 13/07/2015 -

Chapter IV Attitudes to Pastoral Work in England. C. 1560-1640. the Career Structure and Material Rewards Outlined in the Preced

195 Chapter IV Attitudes to Pastoral Work in England. c. 1560-1640. The career structure and material rewards outlined in the preceding chapters are the aspects of the parish ministry which left records obviously capable of analysis and even of measure- ment. No doubt they Shaped the lives and attitudes of the clergy. To see the parish clergy only in these terms, however, is to exclude the pastorate itself, the service which justified the continuance in a Protestant community of a separate order of church officers. Naturally enough the English clergy of the later 16th and early 17th centuries commonly held that theirs was both an honourable and an arduous office, by virtue of the ministry which they performed. The two went together, according to George Downame. "The honour and charge as they be inseperable, so also proportionable; for such as is the weight of the Burden, such is the height of the Honour; and contrariwise." 1 Before the burden and honour are examined as they appeared in the work of the Durham clergy, it would be helpful to know by what standards their efforts were judged. What expectations did clergy and laity entertain of the personal and professional conduct of the pastor? i. Contemporary writing on the pastorate. The most public and formal duties of the minister, those of the liturgy, were laid down in the Prayer Book, although with sufficient ambiguity for both the opponents of vestments 1. G. Downame, 'Of the Dignity and Duty of the Ministry' in G. Hickes, Two Treatises (1711), ii, pp. lxxi-lxxii. -

County Durham Association of Local Councils Annual Report 2018-2019

County Durham Association of Local Councils Annual Report 2018-2019 Horden Welfare Park—Courtesy of Horden Parish Council Report of CDALC Chair 2018-2019 The main impact on parish councils during This was the result of a 2018/19 was the introduction of the Data year long review and Protection Act 2018 and General Data wide consultation Protection Regulations (GDPR) which process. were introduced on the 29 May 2018. The report reviews the This issue was a major concern for parish current framework councils not just in County Durham but governing the behaviour across the country. of local government It was pleasing to eventually read, very councillors and executives in England and close to the Act receiving royal assent, makes a number of recommendations to that clause 7.3 of the Act exempted promote and maintain the standards parish councils from the requirement to expected by the public. Members could appoint a Data Protection Officer. be pleased to hear the following suggestions In some respects this provided, especially our larger councils, the opportunity to a new power for local authorities to overhaul their data systems. Most carried suspend councillors without allowances out a data audit of their current data for up to six months and systems which resulted in councils revised rules on declaring interests, gifts moving away from paper based systems and hospitality to cloud based systems which have local authorities retain ownership of added security built in. their own Codes of Conduct Smaller councils were also impacted by a right of appeal for suspended this legislation too, albeit where data councillors to the Local Government information is concerned, on a smaller Ombudsman scale. -

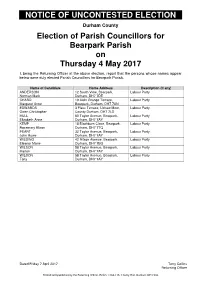

Notice of Uncontested Election

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Durham County Election of Parish Councillors for Bearpark Parish on Thursday 4 May 2017 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Bearpark Parish. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ANDERSON 12 South View, Bearpark, Labour Party Norman Mark Durham, DH7 7DE CHARD 19 Aldin Grange Terrace, Labour Party Margaret Anne Bearpark, Durham, DH7 7AN EDWARDS 3 Flass Terrace, Ushaw Moor, Labour Party Owen Christopher County Durham, DH7 7LD HULL 60 Taylor Avenue, Bearpark, Labour Party Elizabeth Anne Durham, DH7 7AY KEMP 18 Blackburn Close, Bearpark, Labour Party Rosemary Alison Durham, DH7 7TQ PEART 32 Taylor Avenue, Bearpark, Labour Party John Howe Durham, DH7 7AY WILDING 42 Ritson Avenue, Bearpark, Labour Party Eleanor Marie Durham, DH7 7BG WILSON 58 Taylor Avenue, Bearpark, Labour Party Marion Durham, DH7 7AY WILSON 58 Taylor Avenue, Bearpark, Labour Party Tony Durham, DH7 7AY Dated Friday 7 April 2017 Terry Collins Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Room 1/104-115, County Hall, Durham, DH1 5UL NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Durham County Election of Parish Councillors for Bishop Middleham Parish on Thursday 4 May 2017 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Bishop Middleham Parish. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) COOKE 5 High Road, Bishop Middleham, -

Fields, Farms and Sun-Division in a Moorland Region, 1100–1400*

AGHR52_1.qxd 15/06/2007 10:23 Page 20 Fields, farms and sun-division in a moorland region, 1100–1400* by Richard Britnell Abstract Earlier work combining the pre-Black Death charter evidence and post-medieval maps for county Durham has shown how extensive areas of waste survived in the county until the early modern period. This paper begins by considering the enclosed arable land of townships within the larger waste, showing how it was normally held in furlongs which often show evidence of subdivision according to the princi- ples of sun-division. The right to graze the remaining waste is discussed. The Bishops of Durham were in the habit of granting enclosures from the waste by charter: the arable of these enclosed farms might also be divided by sun-division. Recent research in the medieval archives of the bishopric and priory of Durham, in conjunc- tion with cartographic evidence drawn from more recent periods, has established that in county Durham before the twelfth century, small townships, with their fields, were separated from each other by extensive tracts of waste. Land use was modified between the twelfth and early fourteenth centuries, especially in the less heavily settled parts of central Durham, by peasant clearing of new lands and the creation of hundreds of new, compact farms, but even in the early fourteenth century there remained large areas of moor, not only in the land rising west of the Wear, and above the Wear valley, but also in more easterly parts of the county. This abundance of colonizable land was characteristic of many parts of northern Britain: similar landscapes in West Yorkshire, Northumberland and Cumbria have been well described in recent studies, though from types of record different from those available in Durham.1 Though many charac- teristics of such late colonized landscapes are best illustrated in a general overview, any detailed account of how these landscapes developed must rely on concentrations of more local evidence. -

Trades. [Durham

664 FAR TRADES. [DURHAM. FARMERS contmued. Bullerwell Henry, Barlow, Blaydon Charlton John, Pant house, Leadgate Bowron George, Houghton-le-Side, Bullerwell T. High Spen, Newcastle Charlton Joseph, Hilton, Darlington Heighington Bulman Thomas, Hunstanworth, Charlton T. Pitt close, Howden-le-Wr Bowron Thomas, High dyke, Middle- Riding Mill (Northumberland) Charlton Vincent, Blackball Mill, ton-in-Teesdale, Darlington Bulmer Mrs. Simon, Whickham, Hamsterley Colliery Bowron Wm. Gainford, Darlington Swalweli Chrystall William, Fleet shot, Hutton Bowser A. G. S. Bolam, Heighington Bulmer William, Seaton moor, Sea- Henry, Castle Eden Boyd James, Mordon, Ferryhill ton, New Seaham,Seaham Harbour Clapham Louis Charlton,High Thros Boyes Robart, Mordon, Ferryhill Burdon .A.nthony, Bradbury, Ferryhill ton, West Hartlepool Bradford T. A. & J. A. Vigo house, Burdon Mrs. Eleanor, Branch villa, Clark William Edward & John, 'Monk Chester-le-Street Lanchester, Durham Heselden, Castle Eden Bradley Brothers,Aislaby, Eaglescliffe Bur don George, Thrush nest,Eastgate Clark J. East Billingside, Medomsley Bradley Mrs.H.Cox grn.Fence Houses Burdon John Robert,Newbiggin, Red- Clark J. FE>llside, Wbickham.Swalwll Bradley James 0. East Boldon worth, Heighington Clark J. Hill ho. Shadforth, Durham Bradley John, Crimdon house, Hart, Burn Mrs. Margaret & William, Clark John P. Coniscliffe, Darlington West Hartlepool Broom ho. Witton Gilbert, Durhm Clark M.Hallgarth, Pittington,Durhm Bradley Mrs. Mary, Shipley, South Burn .Alexander, Bulam house, Clark Ralph, Shotton, Castle Eden Bedburn, Witton-le-Wear Hulam, Castle Eden Clark Thomas, Mill hill, Castle Eden Bradshaw Edward, West Cornforth Burn Thomas, Wheatley head, West Clark William Henry J.P. Hill house, Braithwaite Waiter & George, Mains Rainton, Fence Hous!ls Ferryhill forth, Ferryhill Burnip William, Westmoor, South Clarlre Jn. -

Subject Guide 11 – Poor Law Records Issue No

Durham County Record Office County Hall Durham DH1 5UL Telephone: 03000 267619 Email: [email protected] Website: www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk Subject Guide 11 – Poor Law Records Issue no. 7 July 2020 Contents Introduction 1 Historical development 1 Old Poor Law 2 New Poor Law 2 Scope and Organisation of this Leaflet 2 Old Poor Law Records 2 New Poor Law Records 3 Other Records 3 Records Held, by Union 3 Auckland Poor Law Union Area 3 Chester le Street Poor Law Union 4 Darlington Poor Law Union 4 Durham Poor Law Union 5 Easington Poor Law Union 5 Gateshead Poor Law Union 6 Hartlepool Poor Law Union (created from Stockton Union in 1859) 6 Houghton-le-Spring Poor Law Union 6 Lanchester Poor Law Union 7 Sedgefield Poor Law Union 7 South Shields Poor Law Union 8 Stockton-on-Tees Poor Law Union 8 Sunderland Poor Law Union 9 Teesdale Poor Law Union 9 Weardale Poor Law Union 10 Introduction This leaflet is a guide to Poor Law records held at Durham County Record Office, in particular those that might have potential for family history research. The aims are: to indicate which of our catalogues should be consulted for further information about record holdings relating to particular places; to explain some of the terminology in use; and to list records which may contain personal information. Many poor law records are subject to a 100 year closure under data protection legislation. Sensitive volumes where the latest record is dated within the last 100 years have a restricted access; contact us for details. -

Our Country Parks, Nature Reserves and Picnic Areas Are Great Places

Barn Owl What we do Our sites We manage and develop our: l Country Parks l Otter Picnic Areas Rockrose l Local Nature Reserves l Railway Paths Our country parks, nature reserves and picnic We l Improve our sites for wildlife and people areas are great places for a family day out l Deliver easy access improvements, wherever possible l Promote the countryside and its conservation l Run a programme of community and corporate volunteering l Run guided walks and events. Volunteer with us You can: l Improve our countryside l Meet new people Involving local communities Northern Brown Argus Countryside volunteers Badger l Share your skills l Learn new skills Durham’s Countryside Service l Keep fit Countryside Sites We have something to suit all ages, abilities and interests . Tel: 03000 264 589 sign up for e-news [email protected] www.durham.gov.uk/countryside Facebook/Durham-Countryside-Volunteers Tel: 03000 264 589 email: [email protected] Images: visit: www.durham.gov.uk/countryside www.wildstock.co.uk Your guide Countryside Service Geoff Hill Stuart Priestley Follow us on Twitter @durhamcouncil Facebook/Durham-Countryside-Volunteers Wingate Quarry Local Nature Reserve 31624 A guide to our country parks, picnic areas, local nature reserves and railway paths © Crown Copyright and database rights 2015. Ordnance Survey LA 100049055 Map Key: Click on the site name for Google link A 5 Country Parks 11 A693 1 Pow Hill – on B6306, 1 mile north of Edmundbyers 2 Waldridge Fell – west of Waldridge Village A692 3 Hardwick Park, on A177, -

The Way of Love Is That Pilgrimage, Particularly in the Middle Ages, Was Viewed As an Act of Devotion

Introduction This guide describes the pilgrimage route between St Hilda’s Church in Hartlepool and Durham Cathedral. All the Northern Saints Trails use the same waymark shown on the left. The total distance is 45.5 kilometres or 28 miles. The route is divided into four sections of between 9 and 15 kilometres. Points of interest are described in red. This pilgrimage route, along with the Ways of Life, Light and Learning, all lead to the shrine of St Cuthbert in Durham. One of the reasons that this route is called The Way of Love is that pilgrimage, particularly in the Middle Ages, was viewed as an act of devotion. One of the most famous pilgrimages to Durham was that of King Canute about a thousand years ago. He is recorded as walking barefoot along the latter part of this route. The church in Kelloe is dedicated to St Helen who was one of the initiators of pilgrimages to the Holy Land. Two other churches at Hart and Trimdon are dedicated to St Mary Magdalene who was known for her great devotion to Christ. St Hilda of Hartlepool was also known for her great devotion to God. Adding the fact that the cathedral is dedicated not just to St Cuthbert, but also to the Blessed Virgin Mary, we can say that this route has a distinctly feminine flavour! Hartlepool was the official port for the County Palatine of Durham, so it is likely that any devotees of St Cuthbert from the continent would have taken this route. If they had met anyone carrying a cross walking in the opposite direc- tion, he would most likely be a fugitive.