2021-06-01-MBTA-Open-Letter.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pathways for Girls: Insights Into the Needs of Young Women in Nubian Square

Pathways for Girls: Insights into the Needs of Young Women in Nubian Square DECEMBER 2019 Pathways for Girls | December 2019 1 The American City Coalition Founded in 1994, The American City Coalition (TACC) is TACC acknowledges the following individuals and a Roxbury-based 501(c)(3) organization committed to organizations for their contributions to the study: providing thought leadership and technical assistance to advance multi-sector and multi-stakeholder partnerships Therese Fitzgerald, PhD, MSW that focus investments to improve the quality of life for Director of Research, TACC Roxbury families. Christine Araujo With Roxbury as a primary focus area, TACC identifies and Executive Director, TACC develops programming and projects that respond to the Charlotte Rice neighborhood’s assets and needs. TACC’s work is grounded Senior Associate, TACC in objective research, in-depth resident input, and the expertise of local stakeholders; these data and analyses Rachele Gardner, MSW allow TACC to help partners identify unmet community Rachele Gardner Consulting needs. Using an emergent approach, TACC seeks to increase collective impact by aligning the skills of partners Yahaira Balestier, Porsha Cole, Carismah Goodman, within defined program areas and identifying and engaging Jael Nunez, Jade Ramirez, Alexandra Valdez complementary partnerships and resources. Youth Researchers, TACC Three interrelated programs guide TACC’s work and reflect Francisco Rodriguez, Intern, Corcoran Center for Real Estate the organization’s focus on connecting people to place: and Urban Action, Boston College d Resident Supports: Connects residents with the essential African Community Economic Development of New services and information needed to support health and England, Cape Verdean Association, Dorchester Bay mobility by working with key stakeholders, including resi- Economic Development Corporation, Freedom House, dents, community organizations, housing communities, Madison Park Development Corporation, and St. -

Downtown Crossing 19-21 School Street, Boston, MA 02108 Space for Lease

Downtown Crossing 19-21 School Street, Boston, MA 02108 Space for Lease DESCRIPTION n 8,131 SF available for lease n Located across from Boston’s 24,000 SF Walgreens, within blocks of Millennium Tower, the Paramount Theater, Boston Opera House n Three-story (plus basement) building located and the Omni Parker House Hotel on School Street near the intersection of Washington Street on the Freedom Trail in Boston’s Downtown Crossing retail corridor n Area retailers: Roche Bobois, Loews Theatre, Macy’s, Staples, Eddie Bauer Outlet, Gap Outlet; The Merchant, Salvatore’s, Teatro, GEM, n Exceptional opportunity for new flagship location Papagayo, MAST’, Latitude 360, Pret A Manger restaurants; Boston Common Coffee Co. and Barry’s Bootcamp n Two blocks from three MBTA stations - Park Street, Downtown Crossing and State Street FOR MORE INFORMATION Jenny Hart, [email protected], 617.369.5910 Lindsey Sandell, [email protected], 617.369.5936 351 Newbury Street | Boston, MA 02115 | F 617.262.1806 www.dartco.com 19-21 School Street, Boston, MA Cambridge East Boston INTERSTATE 49593 North End 1 N Beacon Hill Charles River SITE Financial W E District Boston Common INTERSTATE S 49593 INTERSTATE 49590 Seaport District INTERSTATE Chinatown 49590 1 SITE DATA n Located in the Downtown Crossing Washington Street Shopping District n 35 million SF of office space within the Downtown Crossing District n Office population within 1/2 mile: 190,555 n 2 blocks from the Financial District with approximately 50 million SF of office space DEMOGRAPHICS Residential Average -

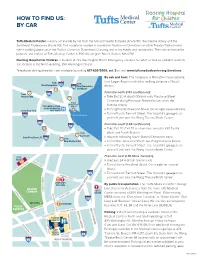

How to Find Us: by Car

HOW TO FIND US: BY CAR Tufts Medical Center is easily accessible by car from the Massachusetts Turnpike (Route 90), the Central Artery and the Southeast Expressway (Route 93). The hospital is located in downtown Boston—in Chinatown and the Theater District—and within walking distance of the Boston Common, Downtown Crossing and many hotels and restaurants. The main entrance for patients and visitors at Tufts Medical Center is 800 Washington Street, Boston, MA 02111. Floating Hospital for Children is located at 755 Washington Street. Emergency services for adult as well as pediatric patients are located at the North Building, 830 Washington Street. Telephone driving directions are available by calling 617-636-5000, ext. 5 or visit www.tuftsmedicalcenter.org/directions. By cab and train: The hospital is a 15-to-20-minute cab ride from Logan Airport and within walking distance of South from from New Hampshire 93 95 New Hampshire Station. 128 and Maine 2 From the north (I-93 southbound): from 95 Western MA » 1 Take Exit 20 A (South Station) onto Purchase Street. Continue along Purchase Street (this becomes the Logan International TUFTS MEDICAL CENTER Airport Surface Artery). & FLOATING HOSPITAL from New York FOR CHILDREN » Turn right onto Kneeland Street. Go straight several blocks. » Turn left onto Tremont Street. The hospital’s garage is on 90 Boston Harbor your left, just past the Wang Theatre/Boch Center. 95 From the south (I-93 northbound): 93 128 » Take Exit 20 (Exit 20 is a two-lane ramp for I-90 East & from West, and South Station). 3 Cape Cod from Providence, RI » Stay left, following South Station/Chinatown signs. -

City of Boston HPRP Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing Program

City of Boston HPRP Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing Program DIRECTORY OF SUB-GRANTEES Updated: March 29, 2010 Homelessness Prevention Providers Action for Boston Community Development (ABCD) Primary Office Neighborhood HPRP Appropriate HPRP Services Special Expertise Second Contacts Location Commonly Served Population(s) Referrals and Program Model and Cultural Language(s) Targeted Competences Capacity In-house Tabitha Gaston 178 Tremont St. Citywide Single Landlords or Landlord engagement & education Marginalized Spanish (617) 348-6449 Boston, MA Office in Individuals Property Early warning system - triage at-risk populations Creole Gaston@Bostonabc 02111 downtown Families Managers with tenancies via support to landlords in general Somali d.org location tenants at-risk Training directly to landlords to solve Housing Cape Verdean Note: Target Landlords problem tenancies/avert search Creole populations seeking help to homelessness Early to be served stabilize tenants Assessment, assistance, stabilization warning Secondary Contact in Public Transportation Location of HPRP “through the and preserve Other Complementary In-House Capacity systems Other Notable event Primary Contact is Access to Office Service Delivery landlord housing Relevant to HPRP HPRP Staff on Vacation or Out Sick door” arrangements – Characteristics/ or divert Capacity Robby Thomas Green Line: Neighborhood household to HEART (Help at-risk Tenant Program) HPRP staff (617) 348-6450 Boylston Street T based outreach new housing = important potential -

State Holds Public Hearing for Shattuck Campus Proposal

THURSDAY, APRIL 15, 2021 PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY SERVING BACK BAY - SOUTH END - FENWAY - KENMORE State holds public hearing for Shattuck Campus proposal By Lauren Bennett portive housing that contributes positively to health outcomes, On April 13, a public hearing and contributes to the supply of was hosted by the state’s Division supportive housing in the region. of Capital Asset Management DCAMM project manager and Maintenance (DCAMM) to Loryn Sheffner explained some present the project proposal for of these goals further at the the Shattuck Hospital campus on public hearing, saying that they Morton St. in Jamaica Plain, and include a “minimum” of 75 to to allow for public comment on 100 supportive housing units, the proposal. as well as “integrated health ser- The Shattuck Hospital plans vices including both services cur- to move to the Newtown Pavil- rently offered on the site and new ion in the South End in 2024, types of services/programs cited and throughout a several year in the Vision Plan,” according to process, the community has been With “activity” going on in the background, Newmarket Business Association Director Sue Sullivan said this a slide presented. week at a press conference that she and some others in the community no longer support the re-opening of outspoken about what should be The state is also looking at the Comfort Station on Atkinson Street. This butts up against a call by neighbors in Worcester Square and done with the campus site. The “other allowable public health Blackstone/Franklin to re-open the Station as soon as possible. -

Market Analysis

NUBIAN SQUARE MARKET ANALYSIS Executive Summary February 2020 The American City Coalition Founded in 1994, The American City Coalition (TACC) is a TACC acknowledges the following individuals and Roxbury-based 501(c)(3) organization committed to providing organizations for their contributions to this study: thought leadership and technical assistance to advance multi- Residents, business owners, employees, and property owners sector and multi-stakeholder partnerships that focus invest- who participated in focus groups, surveys, and interviews ments to improve the quality of life for Roxbury families. Dudley Square Main Streets With Roxbury as a primary focus area, TACC identifies and Joyce Stanley develops programming and projects that respond to the neighborhood’s assets and needs. TACC’s work is grounded Initiative for a Competitive Inner City in objective research, in-depth resident input, and the exper- Steve Grossman tise of local stakeholders; this data and analyses allow TACC Howard Wial to help partners identify unmet community needs. Using an Chris Scott emergent approach, TACC seeks to increase collective Jay Gray impact by aligning the skills of partners within defined program areas and identifying and engaging complementary FXM Associates partnerships and resources. Frank Mahady Dianne Tsitsos Three interrelated programs guide TACC’s work and reflect Jacquelyn Hallsmith the organization’s focus on connecting people to place: Byrne McKinney & Associates • Resident Supports: Connects residents with the essential Pam McKinney services and information needed to support health and mobility; TACC Christine Araujo Economic Development and Asset Development: • David Nardelli Advances strategies that strengthen asset and wealth Charlotte Rice creation pathways; and Carole Walton • Neighborhood Vitality: Supports multi-sector partnerships that improve the neighborhood environment and facilitate investment. -

Key Contributor South End Community Health Center Brings Familiarity and Trust to Vaccination Efforts

THURSDAY, FEBruary 11, 2021 PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY SERVING BACK BAY - SOUTH END - FENWAY - KENMORE Key Contributor South End Community Health Center brings familiarity and trust to vaccination efforts By Seth Daniel then I began to think about it and now I think it’s a blessing As Beverly Rogers sat in the we have this vaccine,” she said. chair at the South End Com- “I remember when I was a kid munity Health Center (SECHC) and they came out with the polio on Monday preparing to get the vaccine. We went in there really Modera COVID-19 vaccination, scared, but it was good.” it wasn’t a snap decision that Rogers heard the opinions of brought her out, but rather a friends in her building, of her eye thoughtful journey about histo- doctor that got the vaccine, her ry, science, vaccines, family and sister, brother-in-law and a niece. community. She even did a little extensive Rogers, who is Cape Verdean, research on the awful medical said she wasn’t one that immedi- experiments done at Tuskegee ately jumped out of the chair and and learned it was blood work ran down to get vaccinated. For and not vaccines that were part her, like a lot of people of color, it of that awful chapter in medical took a journey to get to the exam history. room. The Chapel Street Footbridge, Riverway lit up green as part of the ‘Lights in the Necklace’ series. “I wasn’t so sure at first, but (SECHC , Pg. 5) “Lights in the Necklace” begins this An Historic Victory Saturday on select Emerald Necklace bridges Staff Report be awash with an emerald glow lace bridges, daily from dusk to Former pulse of the Black – thanks to battery-powered 9pm. -

40 Rugg Road Boston (Allston), Ma Supplemental Information Report

40 RUGG ROAD BOSTON (ALLSTON), MA SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION REPORT Submitted To: In Association With: Boston Planning and Development Agency DiMella Shaffer Kittelson & Associates Tech Environmental, Inc. Robinson & Cole LLP AEI Consultants Submitted by: Northeast Geotechnical, Inc. The Michaels Organization Consulting Engineering Services New Ecology, Inc. Solomon McCown Prepared by: Bohler Engineering TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1.0 APPLICANT/PROPONENT INFORMATION ......................................................................... 1-1 Development Team ....................................................................................................... 1-1 Names .................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1.1 Proponent........................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1.1.2 Attorney ............................................................................................................. 1-1 1.1.1.3 Project Consultants and Architects .................................................................... 1-2 Legal Information .......................................................................................................... 1-3 Pending Legal Judgements or Actions Concerning Proposed Project ................... 1-3 History of Property’s Tax Arrears ........................................................................... 1-3 Site Control Over Project ...................................................................................... -

CIVIC AGENDA Right by the “Grove”—The Brick Patio- • TUE, FEB

FEBRUARY WWW.FENWAYNEWS.ORG 2021 FREE COVERING THE FENWAY, AUDUBON CIRCLE, KENMORE SQUARE, UPPER BACK BAY, PRUDENTIAL, LONGWOOD, AND MISSION HILL SINCE 1974 • VOLUME 47, NUMBER 2 • JANUARY 29 - FEBRUARY 26, 2021 FCDC Looks Set to Develop 72 Burbank Project BY ALISON PULTINAS original 32, and all will be income-restricted $1.8 million. The presentation BPDA THE OF COURTESY RENDERING EMBARC he small parking lot at 72 Burbank in perpetuity for households at or below 60 to the Trust estimated the total Street in the East Fens—owned by percent of the area median income (AMI). development cost as $15,117,028. Forest Properties (also known as The reduction in units translated into more Burbank Terrace is also Parkside Tower LLC)—could see units of larger dimensions. The unit mix is in line for low-income tax- a construction start this year. It would be now 8 studios, 7 one-bedroom apartments, credit funding from the state’s T and 12 two-bedrooms. Forest had proposed Department of Housing and Fenway CDC’s version of a proposal already approved for compact apartments. The CDC 13 studios, 12 one-bedrooms, and 7 two- Community Development and Forest Properties signed a purchase-and- bedrooms. (DHCD) winter competition. sale agreement in December; final transactions However, some aspects of the project Although applications were due are expected later this year. have not changed. The units will remain January 21, the CDC won approval When Attorney Marc LaCasse presented rentals and are still undersized, officially in November 2020 through the Forest Properties’ original plan to the Zoning meeting the BPDA’s special compact-living department’s pre-application Board of Appeal on June 25, 2019, the project, standards. -

Institutional Master Plan 2021-2031 Boston Medical Center

Institutional Master Plan 2021-2031 Boston Medical Center May 3, 2021 SUBMITTED TO: Boston Planning and Development Agency One City Hall Square Boston, MA 02201 Submitted pursuant to Article 80D of the Boston Zoning Code SUBMITTED BY: Boston Medical Center Corporation One Boston Medical Center Place Boston, MA 02118 PREPARED BY: Stantec 226 Causeway Street, 6th Floor Boston, MA 02114 617.654.6057 IN ASSOCIATION WITH: Tsoi-Kobus Design VHB DLA Piper Contents 1.0 OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 INSTITUTIONAL MASTER PLAN HISTORY ............................................................... 1-1 1.3 PROGRESS ON APPROVED 2010-2020 IMP PROJECTS ........................................ 1-2 1.4 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES FOR THE 2021-2031 IMP ............................................... 1-3 1.5 A MEASURED APPROACH TO CAMPUS GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY ........... 1-4 1.6 PUBLIC REVIEW PROCESS ...................................................................................... 1-5 1.7 SUMMARY OF IMP PUBLIC AND COMMUNITY BENEFITS ...................................... 1-6 1.8 PROJECT TEAM ......................................................................................................... 1-9 2.0 MISSION AND OBJECTIVES ..................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 OBJECTIVES -

8086 TAP 0221.Docx

Transportation Access Plan 209 Harvard Street Brookline, Massachusetts Prepared for: 209 Harvard Street Development, LLC, c/o CMS Partners Cambridge, Massachusetts February 2021 Prepared by: 35 New England Business Center Drive Suite 140 Andover, MA 01810 TRANSPORTATION ACCESS PLAN 209 HARVARD STREET BROOKLINE, MASSACHUSETTS Prepared for: 209 Harvard Development, LLC c/o CMS Partners P.O. Box 382265 Cambridge, MA 02238 February 2021 Prepared by: VANASSE & ASSOCIATES, INC. Transportation Engineers & Planners 35 New England Business Center, Suite 140 Andover, MA 01810 (978) 474-8800 Copyright © 2021 by VAI All Rights Reserved CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 5 Study Methodology ........................................................................................................ 5 EXISTING CONDITIONS ......................................................................................................... 6 Geometry ........................................................................................................................ 6 2020 Baseline Traffic Volumes ...................................................................................... 7 Pedestrian And Bicycle Facilities ................................................................................... 9 Public Transportation .................................................................................................... -

Harrison Avenue 1135 Roxbury, Ma

HARRISON AVENUE 1135 ROXBURY, MA REDEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY 7,000 SF ZONED RND (ROXBURY NEIGHBORHOOD DISTRICT) LESS THAN 3 MILES TO DOWNTOWN BOSTON PRICE $1,496,000 Colliers International is pleased to present a redevelopment opportunity located on a corner parcel containing a gross site area of 7,000 SF. The lot is zoned Roxbury Neighborhood District (RND) by the City of Boston. The property offers access to two full-access curb cuts on Harrison Avenue and one on Palmer Street. It is conveniently located 0.2 miles from Dudley Station in Nubian Square. It is one mile from State Route 28, one mile from Interstate 93, one mile from State Route 9, and two miles from Interstate 90. Just four miles to Logan International Airport. REDEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY HARRISON AVENUE ROXBURY, MA 7,000 SF FOR SALE 1135 BACK BAY FENWAY SOUTH END WASHINGTON STREET HARRISON AVENUE EXISTING IMPROVEMENTS BUILDING SIZE: 4,227 SF ZONING FAR: 2 CURRENT ZONING: Roxbury Neighborhood MAX HEIGHT: 55' District (RND) ZONING OVERLAY: Overlay District (NDOD) SUBDISTRICT TYPE: Economic Development Area Neighborhood Design ZONING SUB DISTRICT: Dudley Square EDA SITE COVERAGE RATIO: 60.4% CONTACT US Wayne Spiegel SIOR CCIMIM Nancy EmmonsM LEED Green Associate Assistant Vice President Senior Vice President 617 330 8136 508 259 2348 [email protected] [email protected] This document has been prepared by Colliers International for advertising and general information only. Colliers International makes no guarantees, representations or warranties of any kind, expressed or implied, regarding the information including, but not limited to, warranties of content, accuracy 160 Federal Street Floor 11 and reliability.