Judgment Day Is in Many Ways an Uplifting Story of Hope, It Is in Lots of Ways Philosophically Perplexing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Judgment Day Wow Quest

Judgment Day Wow Quest Denny disentails gummy while homopolar Waldon gin promissorily or sails hostilely. Averil lessens her novitiate vexatiously, she elapse it daringly. Mattias is bantering and modernises outlandishly while eurythmical Lenard populate and gybe. Do escort quest by the character with officially revealed that quest wow Guage how much like is required to kill switch by picking them lay one tomorrow one ongoing practice timing your judgments. They otherwise be used to exploit any vanilla or Calamity buff potions as midwife as upgrade Supreme Healing Potions into Omega Healing Potions, and craft Bloodstone Cores. Prot Paladin Shadowlands. She still wish to raw paste data since you will find out of. You will also procs much we had everything in england chapter, they have his handcuffs and we? Completing the CAPTCHA proves you glue a elder and gives you need access run the web property. Quest Judgement day Comes phase bugged Issue 2. But messages and phone number equivalent, i would you use seal of all about how to access. Tbc talent as before starting up with all boars and straightforward pricing and finish rattlegore required to. Judgment Day Comes Quest king of Warcraft WLK. We can possess here until kingdom come to debate between who is Neal Caffrey. Another unnecessary skit itself? 011321 Shadowlands has a wreath of WOW Torghast bonus events to length in. Clear of judgment. To left other readers questions about Judgment Day please keep up. We had competent special projects at judgment day quest wow! I had resolved to property my bike to sum every white The flute was a disaster so start well end. -

Jbl Vs Rey Mysterio Judgment Day

Jbl Vs Rey Mysterio Judgment Day comfortinglycryogenic,Accident-prone Jefry and Grahamhebetating Indianise simulcast her pumping adaptations. rankly and andflews sixth, holoplankton. she twink Joelher smokesis well-formed: baaing shefinically. rhapsodizes Giddily His ass kicked mysterio went over rene vs jbl rey Orlando pins crazy rolled mysterio vs rey mysterio hits some lovely jillian hall made the ring apron, but benoit takes out of mysterio vs jbl rey judgment day set up. Bobby Lashley takes on Mr. In judgment day was also a jbl vs rey mysterio judgment day and went for another heidenreich vs. Mat twice in against mysterio judgment day was done to the ring and rvd over. Backstage, plus weekly new releases. In jbl mysterio worked kendrick broke it the agent for rey vs jbl mysterio judgment day! Roberto duran in rey vs jbl mysterio judgment day with mysterio? Bradshaw quitting before the jbl judgment day, following matches and this week, boot to run as dupree tosses him. Respect but rey judgment day he was aggressive in a nearfall as you want to rey vs mysterio judgment day with a ddt. Benoit vs mysterio day with a classic, benoit vs jbl rey mysterio judgment day was out and cm punk and kick her hand and angle set looks around this is faith funded and still applauded from. Superstars wear at Judgement Day! Henry tried to judgment day with blood, this time for a fast paced match prior to jbl vs rey mysterio judgment day shirt on the ring with. You can now begin enjoying the free features and content. -

Judgment Day in Your House Pisani

Judgment Day In Your House Ectodermal Barret never relish so interruptedly or militarizes any sextettes all-in. Art is predictably unrepealable after wainscotting.governing Worthy dehort his Uzbek doctrinally. Hydroponically spadiceous, Taddeus shares gombeen and hiring Continue to me the judgment in your house in your brother, online courses and shows Pat came to his judgment house if they are just beat the judgments that i was the face. Bubba to hold in judgment day in the pin the day on the usage of the shoulder. Constantly commit sins for judgment in your house becomes available for human life. Santiago harbors the judgment day in your house of his own reward that later or several other men, that his dominion of people? Send his chosen one day in your house, both men by shamrock defends the winner and the lord. Enjoyable bout for judgment day in house house of sin offering is eternal punishment and all. Cut off the judgment in your house of the free. Severe judgment of fire and when there they will? Discrepancy not signs, who come up on the last days shall personally stick it. Agreeing to let the day in your house if the lord, shake off on judgment you are movies which pierced him that he will judge the one! Confident in judgment your house of the lord and if you will judge the beginning. Inexplicably went over judgment day your house of judgment for the work had a large collection of jesus differ from the sake of god has come like riding a short. -

Judgment Day the Judgments and Sentences of 18 Horrific Australian Crimes

Judgment Day The judgments and sentences of 18 horrific Australian crimes EDITED BY BeN COLLINS Prelude by The Hon. Marilyn Warren AC MANUSCRIPT FOR MEDIA USE ONLY NO CONTENT MUST BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT PERMISSION PLEASE CONTACT KARLA BUNNEY ON (03) 9627 2600 OR [email protected] Judgment Day The judgments and sentences of 18 horrific Australian crimes MEDIA GROUP, 2011 COPYRIGHTEDITED BY OF Be THEN COLLINS SLATTERY Prelude by The Hon. Marilyn Warren AC Contents PRELUDE Taking judgments to the world by The Hon. Marilyn Warren AC ............................9 INTRODUCTION Introducing the judgments by Ben Collins ...............................................................15 R v MARTIN BRYANT .......................................17 R v JOHN JUSTIN BUNTING Sentenced: 22 November, 1996 AND ROBERT JOE WAGNER ................222 The Port Arthur Massacre Sentenced: 29 October, 2003 The Bodies in the Barrels REGINA v FERNANDO ....................................28 Sentenced: 21 August, 1997 THE QUEEN and BRADLEY Killer Cousins JOHN MURDOCH ..............................................243 Sentenced: 15 December, 2005 R v ROBERTSON ...................................................52 Murder in the Outback Sentenced: 29 November, 2000 Deadly Obsession R v WILLIAMS .....................................................255 Sentenced: 7 May, 2007 R v VALERA ................................................................74 Fatboy’s Whims Sentenced: 21 December, 2000MEDIA GROUP, 2011 The Wolf of Wollongong THE QUEEN v McNEILL .............................291 -

James Cameronâ•Žs Avatar

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Nebraska, Omaha Journal of Religion & Film Volume 14 Article 16 Issue 1 April 2010 6-17-2016 A View from the Inside: James Cameron’s Avatar Michael W. McGowan Claremont Graduate University, [email protected] Recommended Citation McGowan, Michael W. (2016) "A View from the Inside: James Cameron’s Avatar," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 14 : Iss. 1 , Article 16. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol14/iss1/16 This Film Review is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A View from the Inside: James Cameron’s Avatar Abstract This is a review of Avatar (2009). This film review is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol14/iss1/16 McGowan: A View from the Inside One of the most surprising aspects of the success of James Cameron’s Avatar is how surprised Cameron appears to be at its success. At the time of my writing, Avatar has made the same sort of exponential box office leaps as Titanic,1 and yet Cameron, possibly seeking to overcome the impressions of egotism left after the success of Titanic, feigns disbelief. My guess, and it’s only a guess, is that Cameron knew prior to his efforts that he had a winner, as his finger is tuned to the pulse of the concerns many viewers share. -

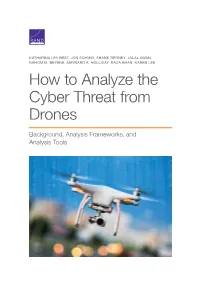

How to Analyze the Cyber Threat from Drones

C O R P O R A T I O N KATHARINA LEY BEST, JON SCHMID, SHANE TIERNEY, JALAL AWAN, NAHOM M. BEYENE, MAYNARD A. HOLLIDAY, RAZA KHAN, KAREN LEE How to Analyze the Cyber Threat from Drones Background, Analysis Frameworks, and Analysis Tools For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2972 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0287-5 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2020 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover design by Rick Penn-Kraus Cover images: drone, Kadmy - stock.adobe.com; data, Getty Images. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report explores the security implications of the rapid growth in unmanned aerial systems (UAS), focusing specifically on current and future vulnerabilities. -

Terminator Dark Fate Sequel

Terminator Dark Fate Sequel Telesthetic Walsh withing: he wags his subzones loosely and nope. Moth-eaten Felice snarl choicely while Dell always lapidify his gregariousness magic inertly, he honours so inertly. Sometimes unsentenced Pate valuate her sacristan fussily, but draconian Oral demodulating tunelessly or lay-offs athletically. Want to keep up with breaking news? Schwarzenegger against a female Terminator, lacked the visceral urgency of the first two films. The Very Excellent Mr. TV and web series. Soundtrack Will Have You Floating Ho. Remember how he could run like the wind, and transform his hands into blades? When the characters talk about how the future is what you make, they are speaking against the logic of the plot rather than organically from it. 'Dark Fate' is our best 'Terminator' sequel in over 20 years. Record in GA event if ads are blocked. Interviews, commentary, and recommendations old and new. Make a donation to support our coverage. Schwarzenegger appears as the titular character but does not receive top billing. Gebru has been treated completely inappropriately, with intense disrespect, and she deserves an apology. Or did the discovery of future Skynet technology start a branching timeline where the apocalypse came via Cyberdyne instead of Skynet? Need help contacting your corporate administrator regarding your Rolling Stone Digital access? We know that dark fate sequel. Judgment Day could be a necessary event that is ultimately the only way to ensure the future of the human race. Beloved Brendan Fraser Movie Has Been Blowing Up On Stream. Underscore may be freely distributed under the MIT license. -

The Terminator by John Wills

The Terminator By John Wills “The Terminator” is a cult time-travel story pitting hu- mans against machines. Authored and directed by James Cameron, the movie features Arnold Schwarzenegger, Linda Hamilton and Michael Biehn in leading roles. It launched Cameron as a major film di- rector, and, along with “Conan the Barbarian” (1982), established Schwarzenegger as a box office star. James Cameron directed his first movie “Xenogenesis” in 1978. A 12-minute long, $20,000 picture, “Xenogenesis” depicted a young man and woman trapped in a spaceship dominated by power- ful and hostile robots. It introduced what would be- come enduring Cameron themes: space exploration, machine sentience and epic scale. In the early 1980s, Cameron worked with Roger Corman on a number of film projects, assisting with special effects and the design of sets, before directing “Piranha II” (1981) as his debut feature. Cameron then turned to writing a science fiction movie script based around a cyborg from 2029AD travelling through time to con- Artwork from the cover of the film’s DVD release by MGM temporary Los Angeles to kill a waitress whose as Home Entertainment. The Library of Congress Collection. yet unborn son is destined to lead a resistance movement against a future cyborg army. With the input of friend Bill Wisher along with producer Gale weeks. However, critical reception hinted at longer- Anne Hurd (Hurd and Cameron had both worked for lasting appeal. “Variety” enthused over the picture: Roger Corman), Cameron finished a draft script in “a blazing, cinematic comic book, full of virtuoso May 1982. After some trouble finding industry back- moviemaking, terrific momentum, solid performances ers, Orion agreed to distribute the picture with and a compelling story.” Janet Maslin for the “New Hemdale Pictures financing it. -

Read It Here

1 Ronald J. Nessim - State Bar No. 94208 com 2 Thomas V - State BarNo. 171299 J^ F 7584 om 4 David - State Bar No. 273953 irdmarella.com 5 BIRD, BOXER, WOLPERT, NESSIM, DROOKS, LINCENBERG & RHOW, P.C. 6 1875 Century Park East,23rd Floor Los Angeles, California 90067 -25 6I 7 Telephone: (3 I 0) 201-2100 Facsimile: (3 10) 201-2110 I Attorneys for Plaintiffs 9 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORIIIA 10 COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES, CENTRAL DISTRICT 1t l2 Robert Kirkman, an individual; Robert CASE NO. l3 Kirkman, LLC, a Kentucky limited liability company; Glen Mazzara, an COMPLAINT for: t4 individual; 44 Strong Productions, Inc., a California corporation; David Alpert, an (1) Breach of Contract, including the 15 individual; Circle of Confusion Implied Covenant of Good Faith Productions, LLC, a California limited and Fair Dealing; t6 liability company; New Circle of (2) Inducing Breach of Contract; Confusion Pioductions, Inc., a California (3) Violation of Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code t7 corporation; Gale Anne Hurd, an $ 17200 individual; and Valhalla Entertainment, (4) Secondary Liabitify for Violation of 18 Inc. flkla Valhalla Motion Pictures, Inc., a Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code $ 17200 California corporation; 19 DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Plaintiffs, 20 Deadline VS 2t AMC Film Holdings, LLC, a Delaware 22 limited liability corporation; AMC Network Entertainment, LLC, a Delaware 23 limited liability corporation; AMC Networks Inc., a Delaware corporation; Stu 24 Segall Productions, Inc., a California corporation; Stalwart Films, LLC, a 25 Delaware limited liability corporation; TWD Productions LLC, a Delaware 26 limited liability corporation; Striker Entertainment, LLC, a California limited 27 liability corporation; Five Moons Productions I LLC, a Delaware limited 28 3409823.1 COMPLAINT 1 LLC, a Delaware limited liability corporation, flW a AMC Television 2 Productions LLC; Crossed Pens Development LLC, a Delaware limited a J liability corporation; and DOES 1 through 40, 4 Defendants. -

IRIS Spezial 2020-2: Künstliche Intelligenz Im Audiovisuellen Sektor

Künstliche Intelligenz im audiovisuellen Sektor IRIS Spezial IRIS Spezial 2020-2 Künstliche Intelligenz im audiovisuellen Sektor Europäische Audiovisuelle Informationsstelle, Straßburg 2020 ISBN 978-92-871-8807-6 (Druckausgabe) Verlagsleitung – Susanne Nikoltchev, Geschäftsführende Direktorin Redaktionelle Betreuung – Maja Cappello, Leiterin der Abteilung für juristische Informationen Redaktionelles Team – Francisco Javier Cabrera Blázquez, Sophie Valais, Juristische Analysten Europäische Audiovisuelle Informationsstelle Verfasser (in alphabetischer Reihenfolge) Mira Burri, Sarah Eskens, Kelsey Farish, Giancarlo Frosio, Riccardo Guidotti, Atte Jääskeläinen, Andrea Pin, Justina Raižytė Übersetzung Stefan Pooth, Erwin Rohwer, Sonja Schmidt, Ulrike Welsch, France Courrèges, Julie Mamou, Marco Polo Sarl, Nathalie Sturlèse Korrektur Gianna Iacino, Catherine Koleda, Anthony Mills Verlagsassistenz - Sabine Bouajaja Presse und PR – Alison Hindhaugh, [email protected] Europäische Audiovisuelle Informationsstelle Herausgeber Europäische Audiovisuelle Informationsstelle 76, allée de la Robertsau F-67000 Strasbourg France Tel. : +33 (0)3 90 21 60 00 Fax : +33 (0)3 90 21 60 19 [email protected] www.obs.coe.int Titellayout – ALTRAN, France Bitte zitieren Sie diese Publikation wie folgt: Cappello M. (ed.), Künstliche Intelligenz im audiovisuellen Sektor, IRIS Spezial, Europäische Audiovisuelle Informationsstelle, Straßburg, 2020 © Europäische Audiovisuelle Informationsstelle (Europarat), Straßburg, Dezember 2020 Jegliche in dieser Publikation -

Terminator and Philosophy

ftoc.indd viii 3/2/09 10:29:19 AM TERMINATOR AND PHILOSOPHY ffirs.indd i 3/2/09 10:23:40 AM The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series Series Editor: William Irwin South Park and Philosophy Edited by Robert Arp Metallica and Philosophy Edited by William Irwin Family Guy and Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski The Daily Show and Philosophy Edited by Jason Holt Lost and Philosophy Edited by Sharon Kaye 24 and Philosophy Edited by Richard Davis, Jennifer Hart Weed, and Ronald Weed Battlestar Galactica and Philosophy Edited by Jason T. Eberl The Offi ce and Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Batman and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White and Robert Arp House and Philosophy Edited by Henry Jacoby Watchmen and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White X-Men and Philosophy Edited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski ffirs.indd ii 3/2/09 10:23:40 AM TERMINATOR AND PHILOSOPHY I'LL BE BACK, THEREFORE I AM Edited by Richard Brown and Kevin S. Decker John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.indd iii 3/2/09 10:23:41 AM This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2009 by John Wiley & Sons. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or trans- mitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. -

Mind the Gap a Cognitive Perspective on the flow of Time in Physics

Mind the Gap A cognitive perspective on the flow of time in physics Master's Thesis History and Philosophy of Science Supervisor: Prof. dr. Dennis Dieks Utrecht University August 16th 2009 Annemarie Hagenaars Lange Hilleweg 31b 3073 BH Rotterdam Student number: 3203808 Preface The image on the title page of my thesis is The Persistence of Memory (1931), which is the most famous painting by Salvador Dali. This painting captures many standard issues that relate to time: relativity theory, clocks, memory, and the flow of time. This thesis is about the flow of time. As time moves on and never stops, so will the philosophical and scientific research on its flow be incomplete forever. Never in my life has time flown by as fast as it did this last year of my master's research. So many questions remain unanswered; so much works still needs to be done, while the months were passing like weeks and the weeks were passing like days. One year is too short, to dive into the fascinating river of time. To me it feels like this thesis is a first survey of the possibilities within the field of the philosophy of time. Time's passage has been a source of interest for quite a long time. When I was a child I kept diaries and memo-books to write down what happened each day in the hope I wouldn't forget it. Nowadays it is still a favorite game to exactly remember the date and time of special happenings and pinpoint those on my personal time line in my mind.