Queen Control Over Reproductive Decisions—No Sexual Deception In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lasius Fuliginosus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Shapes Local Ant Assemblages

NORTH-WESTERN JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY 10 (2): 404-412 ©NwjZ, Oradea, Romania, 2014 Article No.: 141104 http://biozoojournals.ro/nwjz/index.html Lasius fuliginosus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) shapes local ant assemblages Piotr ŚLIPIŃSKI1,*, Bálint MARKÓ2, Kamil RZESZOWSKI1, Hanna BABIK1 and Wojciech CZECHOWSKI1 1. Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Wilcza 64, 00-679 Warsaw, Poland, E-mails: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 2. Hungarian Department of Biology and Ecology, Babeş-Bolyai University, Clinicilor str. 5-7, 400006 Cluj-Napoca, Romania, E-mail: [email protected]. * Corresponding author, P. Ślipiński, E-mail: [email protected] Received: 20. December 2013 / Accepted: 22. March 2014 / Available online: 17. October 2014 / Printed: December 2014 Abstract. Interspecific competition is a major structuring force in ant assemblages. The assemblages are organized hierarchically, with territorial species as top competitors. In boreal areas and in the temperate deciduous forest biome common territorials are species of the subgenus Formica s. str. They are well known for their negative impact on lower-ranked ant species. Less is known, though the structuring role of Lasius fuliginosus, another territorial ant species. Some earlier studies have shown or suggested that it may restrictively affect subordinate species (including direct predation toward them) even stronger than wood ants do. In the present study we compared species compositions and nest densities of subordinate ant species within and outside territories of L. fuliginosus. The results obtained confirmed that this species visibly impoverishes both qualitatively (reduced species richness, altered dominance structures) and quantitatively (decreased nest densities) ant assemblages within its territories. -

The Role of Ant Nests in European Ground Squirrel's (Spermophilus

Biodiversity Data Journal 7: e38292 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.7.e38292 Short Communications The role of ant nests in European ground squirrel’s (Spermophilus citellus) post-reintroduction adaptation in two Bulgarian mountains Maria Kachamakova‡‡, Vera Antonova , Yordan Koshev‡ ‡ Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research at Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, Bulgaria Corresponding author: Maria Kachamakova ([email protected]) Academic editor: Ricardo Moratelli Received: 16 Jul 2019 | Accepted: 09 Sep 2019 | Published: 07 Oct 2019 Citation: Kachamakova M, Antonova V, Koshev Y (2019) The role of ant nests in European ground squirrel’s (Spermophilus citellus) post-reintroduction adaptation in two Bulgarian mountains. Biodiversity Data Journal 7: e38292. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.7.e38292 Abstract The European ground squirrel (Spermophilus citellus) is a vulnerable species, whose populations are declining throughout its entire range in Central and South-Eastern Europe. To a great extent, its conservation depends on habitat restoration, maintenance and protection. In order to improve the conservation status of the species, reintroductions are increasingly applied. Therefore, researchers focus their attention on factors that facilitate these activities and contribute to their success. In addition to the well-known factors like grass height and exposition, others, related to the underground characteristics, are more difficult to evaluate. The presence of other digging species could help this evaluation. Here, we present two reintroduced ground squirrel colonies, where the vast majority of the burrows are located in the base of anthills, mainly of yellow meadow ant (Lasius flavus). This interspecies relationship offers numerous advantages for the ground squirrel and is mostly neutral for the ants. -

Is Lasius Bicornis (Förster, 1850) a Very Rare Ant Species?

Bulletin de la Société royale belge d’Entomologie/Bulletin van de Koninklijke Belgische Vereniging voor Entomologie, 154 (2018): 37–43 Is Lasius bicornis (Förster, 1850) a very rare ant species? (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) François VANKERKHOVEN1, Luc CRÈVECOEUR2, Maarten JACOBS3, David MULS4 & Wouter DEKONINCK5 1 Mierenwerkgroep Polyergus, Wolvenstraat 9, B-3290 Diest (e-mail: [email protected]) 2 Provinciaal Natuurcentrum, Craenevenne 86, B-3600 Genk (e-mail: [email protected]) 3 Beukenlaan 14, B-2200 Herentals (e-mail: [email protected]) 4 Tuilstraat 15, B-1982 Elewijt (e-mail: [email protected]) 5 Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Vautierstraat 29, B-1000 Brussels (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract Since its description based on a single alate gyne by the German entomologist Arnold Förster, Lasius bicornis (Förster, 1850), previously known as Formicina bicornis, has been sporadically observed in the Eurasian region and consequently been characterized as very rare. Here, we present the Belgian situation and we consider some explanations for the status of this species. Keywords: Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Lasius bicornis, faunistics, Belgium Samenvatting Vanaf de beschrijving door de Duitse entomoloog Arnold Förster, werd Laisus bicornis (Förster, 1850), voordien Formicina bicornis en beschreven op basis van een enkele gyne, slechts sporadisch waargenomen in de Euraziatische regio. De soort wordt dan meer dan 150 jaar later als ‘zeer zeldzaam’ genoteerd. In dit artikel geven we een overzicht van de Belgische situatie en overwegen enkele punten die de zeldzaamheid kunnen verklaren. Résumé Depuis sa description par l’entomologiste allemand Arnold Förster, Lasius bicornis (Förster, 1850), anciennement Formicina bicornis décrite sur base d'une seule gyne ailée, n'a été observée que sporadiquement en Eurasie, ce qui lui donne un statut de «très rare». -

A Phylogenetic Analysis of North American Lasius Ants Based on Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA Trevor Manendo University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2008 A Phylogenetic Analysis of North American Lasius Ants Based on Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA Trevor Manendo University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Recommended Citation Manendo, Trevor, "A Phylogenetic Analysis of North American Lasius Ants Based on Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA" (2008). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 146. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/146 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A phylogenetic analysis of North American Lasius ants based on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA. A Thesis Presented by Trevor Manendo to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Specializing in Biology May, 2008 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science specializing in Biology. Thesis Examination Committee: ice President for Research and Dean of Graduate Studies Date: March 19,2008 ABSTRACT The ant genus Lasius (Formicinae) arose during the early Tertiary approximately 65 million years ago. Lasius is one of the most abundant and widely distributed ant genera in the Holarctic region, with 95 described species placed in six subgenera: Acanthomyops, Austrolasius, Cautolasius, Chthonolasius, Dendrolasius and Lasius. -

Above-Belowground Effects of the Invasive Ant Lasius Neglectus in an Urban Holm Oak Forest

U B Universidad Autónoma de Barce lona Departamento de Biología Animal, de Biología Vegetal y de Ecología Unidad de Ecología Above-belowground effects of the invasive ant Lasius neglectus in an urban holm oak forest Tesis doctoral Carolina Ivon Paris Bellaterra, Junio 2007 U B Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona Departamento de Biología Animal, de Biología Vegetal y de Ecología Unidad de Ecología Above-belowground effects of the invasive ant Lasius neglectus in an urban holm oak forest Memoria presentada por: Carolina Ivon Paris Para optar al grado de Doctora en Ciencias Biológicas Con el Vº. Bº.: Dr Xavier Espadaler Carolina Ivon Paris Investigador de la Unidad de Ecología Doctoranda Director de tesis Bellaterra, Junio de 2007 A mis padres, Andrés y María Marta, y a mi gran amor Pablo. Agradecimientos. En este breve texto quiero homenajear a través de mi más sincero agradecimiento a quienes me ayudaron a mejorar como persona y como científica. Al Dr Xavier Espadaler por admitirme como doctoranda, por estar siempre dispuesto a darme consejos tanto a nivel profesional como personal, por darme la libertad necesaria para crecer como investigadora y orientarme en los momentos de inseguridad. Xavier: nuestras charlas más de una vez trascendieron el ámbito académico y fue un gustazo escucharte y compartir con vos algunos almuerzos. Te prometo que te enviaré hormigas de la Patagonia Argentina para tu deleite taxonómico. A Pablo. ¿Qué puedo decirte mi amor qué ya no te haya dicho? Gracias por la paciencia, el empuje y la ayuda que me diste en todo momento. Estuviste atento a los más mínimos detalles para facilitarme el trabajo de campo y de escritura. -

A New Synonymy in the Subgenus Dendrolasius of the Genus Lasius (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Formicinae)

Bull. Natn. Sci. Mus., Tokyo, Ser. A, 31(3), pp. 115–117, September 22, 2005 A New Synonymy in the Subgenus Dendrolasius of the Genus Lasius (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Formicinae) Munetoshi Maruyama Department of Zoology, National Science Museum, Hyakunin-chô 3–23–1, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, 169–0073 Japan e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Lasius (Dendrolasius) morisitai Yamauchi, 1978, was synonymized with L. (D.) capi- tatus (Kusnetzov-Ugamsky, 1928). An annotated list of the Japanese species of Dendrolasius is given, which corresponds to the names in the Ant Color Image Database. Key words : Lasius morisitai, Lasius capitatus, Japanese Ant Color Image Database. The genus Lasius Fabricius, 1804, is among far east of Russia, near the type locality of L. the most difficult groups to classify in the taxon- capitatus, and collected several workers of a omy of ants because of the paucity of morpho- Dendrolasius species that were well suited to the logical information that is needed to distinguish redescription of the L. capitatus types by Rad- species. Many taxonomic problems relating to chenko (2005). I was also able to examine the precise identification remain unresolved, espe- type material of L. morisitai. After considering cially in the East Palearctic species, and compre- the morphological characteristics of this material, hensive systematic study based on examination I came to the conclusion that L. capitatus and L. of type specimens is required. morisitai were synonymous. Lasius morisitai is Radchenko (2005) revised the East Palearctic herein synonymized with L. capitatus. species of the subgenus Dendrolasius Ruzsky, Additionally, an annotated list of the Japanese 1912, genus Lasius, and recognized six species in species of Dendrolasius corresponding to the the subgenus: L. -

Moisture Ants

Extension Bulletin 1382 insect answers MOISTURE ANTS Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) are an easily rec- but is usually white and is always legless. The pupal ognized group of social insects. The workers are stage looks like the adult but is soft, white and wingless, all possess elbowed antennae and all have motionless. Many are enclosed in a cocoon of a a petiole (narrow constriction) of one or two segments brownish or whitish papery material. between the thorax and the abdomen. Ants produce reproductive forms usually at one time Most ant colonies are started by a single, inseminated of the year (spring or fall, depending on species and female or queen. From this single individual colo- colony disposition). Colony activity at the time of nies can grow to contain anywhere from several hun- reproductive swarming is high, with winged males dred to several thousand individuals. and queens and workers in a very active state. The queen and males fly from the colony and mate. Ants normally have three distinct castes: workers, Shortly after mating, the male dies. The inseminated queens and males. Males are intermediate in size queen then builds a small nest, lays a few eggs and between queens and workers and can be recognized nurtures the developing larvae that soon hatch. When by ocelli (simple “eyes”) on top of the head, wings, adult workers appear, they take over the function of protruding genitalia and large eyes. The sole func- caring for the queen and larvae, building the nest and tion of the male is to mate with the queen. bringing in food for the colony. -

Species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Formicinae) in Late Eocene Rovno Amber

JHR 82: 237–251 (2021) doi: 10.3897/jhr.82.64599 RESEARCH ARTICLE https://jhr.pensoft.net Formica species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Formicinae) in late Eocene Rovno amber Alexander G. Radchenko1, Evgeny E. Perkovsky1, Dmitry V. Vasilenko2,3 1 Schmalhausen Institute of zoology of National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Kiev, 01030, Ukraine 2 Bo- rissiak Paleontological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 117647, Russia 3 Cherepovets State University, Cherepovets, 162600, Russia Corresponding author: Alexander G. Radchenko ([email protected]) Academic editor: F.H. Garcia | Received 18 February 2021 | Accepted 7 April 2021 | Published 29 April 2021 http://zoobank.org/D68193F7-DFC4-489E-BE9F-4E3DD3E14C36 Citation: Radchenko AG, Perkovsky EE, Vasilenko DV (2021) Formica species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Formicinae) in late Eocene Rovno amber. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 82: 237–251. https://doi.org/10.3897/ jhr.82.64599 Abstract A new species, Formica ribbeckei Radchenko & Perkovsky, sp. nov., is described based on four workers from late Eocene Rovno amber (Ukraine). It most resembles F. flori Mayr, 1868 but differs from the latter mainly by the 5-segmented maxillary palps with the preapical segment subequal in length to the apical one, and by the shorter first funicular segment. Fossil F. luteola Presl, 1822, F. trigona Presl, 1822, F. mac- rognatha Presl, 1822 and F. quadrata Holl, 1829 are considered incertae sedis in Formicidae. Thus, ten valid Formica Linnaeus, 1758 species (including F. ribbeckei) are known now from late Eocene European ambers. The diversity of Formica in the early and middle Eocene deposits of Eurasia and North America is considered. It is assumed that the genus Formica most likely arose in the early Eocene. -

2561 Seifert Lasius 1992.Pdf

. 1 ABHANDLUNGEN UND BERICHTE DES NATURKUNDEMUSEUMS GORLITZ Band 66, Nummer 5 Abh. Ber. Naturkundemus. Gorlitz 66, 5: 1-67 (1992) ISSN 0373-7568 Manuskriptannahme am 25. 5. 1992 Erschienen am 7. 8. 1992 A Taxonomic Revision of the Palaearctic Members of the Ant Subgenus Lasius s. str. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) BERNHARD SEIFERT With 9 tables and 41 figures Abstract 33 species and one distinct subspecies of the ant subgenus Lasius s.str. are described for the Palaearctic region, including 1 7 species described as new and 8 taxa raised to species level. 1 taxa are synonymized and 12 taxa cannot be interpreted because of insufficient descriptions and unavailability of types. A total of 5050 specimens was studied and 3660 specimens were evaluated numerically giving 27 000 primary data on morphology. In the numeric analysis, the body-size-dependent variability was removed by consideration of allometric functions. The species'descriptions are supplemented by comments on differential characters and taxonomic status, by information on distribution and biology and by figures of each species. A key to the workers and comparative tables on numeric characters are provided. Zusammenfassung Eine taxonomische Revision der palaarktischen Vertreter des Ameisensubgenus Lasius s.str. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). 33 Spezies und eine distinkte Subspezies, darunter 17 neubeschriebene Spezies und 8 zum Art- niveau erhobene Taxa, werden fur den Subgenus Lasius s. str. fur die Palaarktische Region beschrieben. 1 1 Taxa werden synonymisiert und 12 Namen koimen wegen unzureichender Beschrei- bungen und des Fehlens von Typen nicht interpretiert werden. Ein Gesamtmaterial von 5050 Exem- plaren wurde untersucht, davon 3660 Exemplare mittels numerischer Merkmalsbeschreibimg, was 27 000 morphologische Primardaten ergab. -

Nest Complexes Under the Influence of Anthropogenic Factors

Serangga 2020, 25(3): 160-178 Stukalyuk & Goncharenko SHIFT IN THE STRUCTURE OF Lasius flavus (HYMENOPTERA, FORMICIDAE) NEST COMPLEXES UNDER THE INFLUENCE OF ANTHROPOGENIC FACTORS Stanislav Stukalyuk* & Igor Goncharenko Institute for Evolutionary Ecology National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Acad. Lebedeva str., 37, Kyiv, 03143, Ukraine. *corresponding author: [email protected]. ABSTRACT The structure of five Lasius flavus Fabricius, 1781 (yellow meadow ant) nest complexes with 33 to 211 nest mounds exposed to the anthropogenic impact of varying intensity was studied in 2001 and 2014 from four locations in Crimea. The study areas can be arranged in order of increasing intensity of anthropogenic impact as follows: the Chatyr-Dag Mountain (no impact, two nest complexes), arboretum near Simferopol city (low-intensity impact, moderate grazing, one nest complex), the outskirts of Kurtsy village (high-intensity impact, intensive grazing, ne nest complex), and Gagarinsky Park (critical level of intensity, draining, one nest complex). In 2001, mound measurements were taken from all nest complexes, divided into squares of 20 × 20 m. In 2014, mound measurements were taken from three out of five locations, namely the Chatyr-Dag Mountain (one nest complex), Kurtsy village, and Gagarinsky Park). In 2014, the nest complex in Gagarinsky Park was found to no longer exist. Other nest complexes underwent significant changes. Small nest mounds either disappeared or grew in size. The total nest volume did not change significantly or slightly increased. Therefore, this study concluded that grazing did not affect the ability of nest complexes to grow. The lowering of the groundwater table was found to be a critical factor. -

Sensitivity and Feeding Efficiency of the Black Garden Ant Lasius Niger to Sugar Resources

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by HAL-Rennes 1 Sensitivity and feeding efficiency of the black garden ant Lasius niger to sugar resources Claire Detrain, Jacques Prieur To cite this version: Claire Detrain, Jacques Prieur. Sensitivity and feeding efficiency of the black garden ant Lasius niger to sugar resources. Journal of Insect Physiology, Elsevier, 2014, 64, pp.74 - 80. <10.1016/j.jinsphys.2014.03.010>. <hal-01016466> HAL Id: hal-01016466 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01016466 Submitted on 30 Jun 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. Sensitivity and feeding efficiency of the black garden ant Lasius niger to sugar resources ⇑ Claire Detrain a, , Jacques Prieur b a Service d’Ecologie Sociale CP 231, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 50 avenue F. Rossevelt, B-1050 Bruxelles, Belgium b UMR 6552 ETHOS, University of Rennes 1, CNRS Biological Station, 35380 Paimpont, France abstract Carbohydrate sources such as plant exudates, nectar and honeydew represent the main source of energy for many ant species and contribute towards maintaining their mutualistic relationships with plants or aphid colonies. -

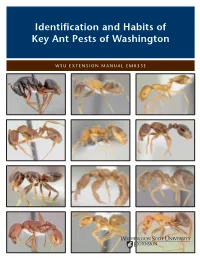

Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington

Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington WSU EXTENSION MANUAL EM033E Cover images are from www.antweb.org, as photographed by April Nobile. Top row (left to right): Carpenter ant, Camponotus modoc; Velvety tree ant, Liometopum occidentale; Pharaoh ant, Monomorium pharaonis. Second row (left to right): Aphaenogaster spp.; Thief ant, Solenopsis molesta; Pavement ant, Tetramorium spp. Third row (left to right): Odorous house ant, Tapinoma sessile; Ponerine ant, Hypoponera punctatissima; False honey ant, Prenolepis imparis. Bottom row (left to right): Harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex spp.; Moisture ant, Lasius pallitarsis; Thatching ant, Formica rufa. By Laurel Hansen, adjunct entomologist, Washington State University, Department of Entomology; and Art Antonelli, emeritus entomologist, WSU Extension. Originally written in 1976 by Roger Akre (deceased), WSU entomologist; and Art Antonelli. Identification and Habits of Key Ant Pests of Washington Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) are an easily anywhere from several hundred to millions of recognized group of social insects. The workers individuals. Among the largest ant colonies are are wingless, have elbowed antennae, and have a the army ants of the American tropics, with up petiole (narrow constriction) of one or two segments to several million workers, and the driver ants of between the mesosoma (middle section) and the Africa, with 30 million to 40 million workers. A gaster (last section) (Fig. 1). thatching ant (Formica) colony in Japan covering many acres was estimated to have 348 million Ants are one of the most common and abundant workers. However, most ant colonies probably fall insects. A 1990 count revealed 8,800 species of ants within the range of 300 to 50,000 individuals.