Buddhist Psychology the Quest Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Concept of Self-Liberation in Theravada Burmese Buddhism

ASIA-PACIFIC NAZARENE THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY THE CONCEPT OF SELF-LIBERATION IN THERAVADA BURMESE BUDDHISM A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Asia-Pacific Nazarene Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfilment of the Degree Master of Science in Theology BY CING SIAN THAWN TAYTAY, RIZAL NOVEMBER 2020 ASIA-PACIFIC NAZARENE THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY WE HEREBY APPROVE THE THESIS SUBMITTED BY Cing Sian Thawn ENTITLED THE CONCEPT OF SELF-LIBERATION IN THERAVADA BURMESE BUDDHISTS AS PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THEOLOGY (SYSTEMATIC THEOLOGY) Dr. Dick Eugenio _________ Dr. Phillip Davis __________ Thesis Adviser Date Program Director Date Dr. Eileen Ruger _________ Dr. Naw Yaw Yet ___________ Internal Reader Date External Reader Date Dr. Dick Eugenio _________ Dr. Larry Bollinger ___________ Academic Dean Date President Date ii ABSTRACT This thesis explores the self-liberation concept of Theravada Buddhism, with the hope that it can provide a foundation towards a dialogical exchange between Buddhists and Christians in Myanmar. To provide a better understanding of the context, the thesis offers a brief historical background of Buddhist-Christian relations in Myanmar. By mainly relying on the translation of the Pali Tipitaka, along with a number of secondary sources from prominent Buddhist scholars, the self-liberation concept of Theravada Buddhism is discussed, beginning with the personal experience of Gotama, the Buddha. The thesis is descriptive in nature. The research employs a basic qualitative method, integrated with the analytical and interpretive methods. Correlation and synthesis were done and are presented in the final chapter with an emphasis on implications for interfaith dialogue. The study produced some significant findings. -

The Mind-Body in Pali Buddhism: a Philosophical Investigation

The Mind-Body Relationship In Pali Buddhism: A Philosophical Investigation By Peter Harvey http://www.buddhistinformation.com/mind.htm Abstract: The Suttas indicate physical conditions for success in meditation, and also acceptance of a not-Self tile-principle (primarily vinnana) which is (usually) dependent on the mortal physical body. In the Abhidhamma and commentaries, the physical acts on the mental through the senses and through the 'basis' for mind-organ and mind-consciousness, which came to be seen as the 'heart-basis'. Mind acts on the body through two 'intimations': fleeting modulations in the primary physical elements. Various forms of rupa are also said to originate dependent on citta and other types of rupa. Meditation makes possible the development of a 'mind-made body' and control over physical elements through psychic powers. The formless rebirths and the state of cessation are anomalous states of mind-without-body, or body-without-mind, with the latter presenting the problem of how mental phenomena can arise after being completely absent. Does this twin-category process pluralism avoid the problems of substance- dualism? The Interaction of Body and Mind in Spiritual Development In the discourses of the Buddha (Suttas), a number of passages indicate that the state of the body can have an impact on spiritual development. For example, it is said that the Buddha could only attain the meditative state of jhana once he had given up harsh asceticism and built himself up by taking sustaining food (M.I. 238ff.). Similarly, it is said that health and a good digestion are among qualities which enable a person to make speedy progress towards enlightenment (M.I. -

31 Planes of Existence (1)

31 Planes of Existence (1) Kamaloka Realms Death & Rebirth All putthujjhanas are subjected to death & rebirths “Death proximate kamma” or last thoughts moment leads to the realm of rebirth. Good or bad, it tends to be the state of mind characteristic of the being in his previous life It could be hate, metta, karuna, tanha, and so on. Tanha is the one that binds us to Samsara, esp the sensual worlds Depends on 3 types of action (mental, physical & vocal manifesting in thought, action & speech) Purified consciousness leads to birth in higher planes such as Brahma lokas Mixed type will lead to birth in the intermediate planes of kama lokas Predominantly bad kamma will lead to birth in the Duggatti (unhappy states) 1 Only humans on earth? Early Buddhist texts (Nikaya), mentioned: “the thousandfold world system” “the twice thousandfold world system” “the thrice thousandfold world system” Buddhaghosa said there are 1,000,000,000,000 world systems 3 Types of Worlds Kama-loka or kamabhava (sensuous world) 11 planes Rupa-loka or rupabhava (the world of form or fine material world) 16 planes Arupa-loka or arupabhava (the formless world / immaterial world) 4 planes 2 Kama-Loka The sensuous world is divided into Kamaduggati (those states that are not desirable and unsatisfactory with unpleasant and painful feelings) Kamasugati (those states that are desirable or satisfying with pleasant and pleasurable feelings) Kamaduggati Bhumi 4 States of Suffering (Apaya) Niraya (Hell) Tiracchana Yoni (Animals) Peta Loka (Hungry ghosts) Asura (Demons) 3 Niraya (Hell) Lowest level of existence with Devoid of sukha. Only non-stop unimaginable suffering & anguish Dukha. -

The King of Siam's Edition of the Pāli Tipiṭaka

JOURNAL THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY. ART. I.—The King of Slant's Edition of the Pali Tipitaka. By ROBERT CHALMERS. THOUGH four years have passed since the publication, at Bangkok, of thirty-nine volumes of the Pali Canon, under the auspices of His Majesty the King of Siam,1 it was not till a more recent date that, thanks to His Majesty's munificence, copies of this monumental work reached the Royal Asiatic Society, and other libraries in Europe, and so became available for study by Western scholars. The recent visit of the King to this country gave me an oppor- tunity of discussing the genesis and circumstances of the edition with H.R.H. Prince Sommot; and I now desire to communicate to the Royal Asiatic Society the information which I owe to the Prince's scholarship and courtesy. The value of that information will be recognized when it is "stated that Prince Sommot is Private Secretary to the King, served on the Editing Committee, and is brother to the Priest-Prince Vajirafianavarorasa, who has edited eleven out of the thirty-nine volumes already published. 1 His Majesty has informed the Society that there will follow in due course an edition of the Atthakathas and Tikas. J.R.A.8. 1898. 1 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Exeter, on 11 May 2018 at 02:56:23, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0035869X0014612X 2 THE KING OF SIAM'S The first matter which I sought to clear up was the purport of the Siamese preface prefixed to every volume. -

Chronology of the Pali Canon Bimala Churn Law, Ph.D., M.A., B.L

Chronology of the Pali Canon Bimala Churn Law, Ph.D., M.A., B.L. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Researchnstitute, Poona, pp.171-201 Rhys Davids in his Buddhist India (p. 188) has given a chronological table of Buddhist literature from the time of the Buddha to the time of Asoka which is as follows:-- 1. The simple statements of Buddhist doctrine now found, in identical words, in paragraphs or verses recurring in all the books. 2. Episodes found, in identical words, in two or more of the existing books. 3. The Silas, the Parayana, the Octades, the Patimokkha. 4. The Digha, Majjhima, Anguttara, and Samyutta Nikayas. 5. The Sutta-Nipata, the Thera-and Theri-Gathas, the Udanas, and the Khuddaka Patha. 6. The Sutta Vibhanga, and Khandhkas. 7. The Jatakas and the Dhammapadas. 8. The Niddesa, the Itivuttakas and the Patisambbhida. 9. The Peta and Vimana-Vatthus, the Apadana, the Cariya-Pitaka, and the Buddha-Vamsa. 10. The Abhidhamma books; the last of which is the Katha-Vatthu, and the earliest probably the Puggala-Pannatti. This chronological table of early Buddhist; literature is too catechetical, too cut and dried, and too general to be accepted in spite of its suggestiveness as a sure guide to determination of the chronology of the Pali canonical texts. The Octades and the Patimokkha are mentioned by Rhys Davids as literary compilations representing the third stage in the order of chronology. The Pali title corresponding to his Octades is Atthakavagga, the Book of Eights. The Book of Eights, as we have it in the Mahaniddesa or in the fourth book of the Suttanipata, is composed of sixteen poetical discourses, only four of which, namely, (1.) Guhatthaka, (2) Dutthatthaka. -

SUMMARY and COMMENTS the Portrait Which Emerges from The

CHAPTER EIGHT SUMMARY AND COMMENTS The portrait which emerges from the references to Mara in the early Indian Buddhist literature is essentially the following. On the one hand Mara is the name of a deva of high status within the cosmology of early Buddhists. On the other hand the term "Mara" meaning "death" is identified with the plurality of conditions and defilements of samsara. This ambivalence as well as versatility of the Mara references is summarized in the four-Maras formula. The skandhamiira epitomizes all the conditions of samsara that are subject to death (miyati). The kleSamiira epitomizes one's own karmic acts of defilement and sense desire that result in "death" (internal miiretii). The devaputramiira refers to some external causal agent, force or event which lies outside one's own control and which also results in "death" (external miiretii). Finally, mrtyumiira marks the essential character basic to all types of reference to Mara, encompassing all conditions and events of samsara as well as the deeds of the Mara deva, namely mrtyu, "death-itself." "Death" for the early Indian Buddhist refers to continual death after rebirth. The nature and power of the devaputramiira (Miira papimii) is described in the selected texts in the following way. Mara is a deva with a mind-made body, who together with the six classes of devas in the Kamaloka, enjoys the maturing of his good karma. Though virtuous and long-lived, Mara is subject to impermanence and sorrow like all beings in samsara. As the "Lord of the world of desire," however, Mara enjoys the splendor and majesty of his cosmological position as Chief of the Paranirmitavasavartin devas, the highest class of devas in the Kamaloka. -

What Buddhists Believe Expanded 4Th Edition

WhatWhat BuddhistBuddhist BelieveBelieve Expanded 4th Edition Dr. K. Sri Dhammanada HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. Published by BUDDHIST MISSIONARY SOCIETY MALAYSIA 123, Jalan Berhala, 50470 Kuala Lumpur, 1st Edition 1964 Malaysia 2nd Edition 1973 Tel: (603) 2274 1889 / 1886 3rd Edition 1982 Fax: (603) 2273 3835 This Expanded Edition 2002 Email: [email protected] © 2002 K Sri Dhammananda All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any in- formation storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover design and layout Sukhi Hotu ISBN 983-40071-2-7 What Buddhists Believe Expanded 4th Edition K Sri Dhammananda BUDDHIST MISSIONARY SOCIETY MALAYSIA This 4th edition of What Buddhists Believe is specially published in conjunction with Venerable Dr K Sri Dhammananda’s 50 Years of Dhammaduta Service in Malaysia and Singapore 1952-2002 (BE 2495-2545) Photo taken three months after his arrival in Malaysia from Sri Lanka, 1952. Contents Forewordxi Preface xiii 1 LIFE AND MESSAGE OF THE BUDDHA CHAPTER 1 Life and Nature of the Buddha Gautama, The Buddha 8 His Renunciation 24 Nature of the Buddha27 Was Buddha an Incarnation of God?32 The Buddha’s Service35 Historical Evidences of the Buddha38 Salvation Through Arahantahood41 Who is a Bodhisatva?43 Attainment of Buddhahood47 Trikaya — The Three Bodies of the Buddha49 -

Theravada Buddhism in Thailand: As Represented by Buddhist and Christian Writings from Thailand in the Period 1950-2000

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs A study of the dialogue between Christianity and Theravada Buddhism in Thailand: as represented by Buddhist and Christian writings from Thailand in the period 1950-2000 Thesis How to cite: Boon-Itt, Bantoon (2008). A study of the dialogue between Christianity and Theravada Buddhism in Thailand: as represented by Buddhist and Christian writings from Thailand in the period 1950-2000. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2007 Bantoon Boon-Itt https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000fd77 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk u a j -r£jcjT6fc A study of the dialogue between Christianity andTheravada Buddhism in Thailand as represented by Buddhist and Christian writings from Thailand in the period 1950 - 2000. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Religious Studies The Open University St John’s College, Nottingham December 2007 Revd Bantoon Boon-Itt B.Th., B.D., M.A. a f <Si/gASsSSf<W /<£ 3 )ec<£;/<,&<=/£. '&A-7'c Of Ou/V& -2AO&’ ProQuest Number: 13890031 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Lecture 143: the Magic of a Mahayana Sutra Mr Chairman, and Friends

Lecture 143: the Magic of A Mahayana Sutra Mr Chairman, and friends. Let's imagine that someone asks us to describe our lives. Suppose we were asked by them to say what it was essentially and specifically that characterized our lives as we ordinarily live them. I wonder what sort of reply, what sort of answer most of us would give? I wonder what most of us would have to say? That is to say, those of us who are quite ordinary people, not pop stars, not politicians, and certainly not T.V. personalities. Most of us, most ordinary people would say, that our lives more often than not, are characterized, by sameness. We'd say perhaps that we seem to spend most of our time doing much the same sort of things in very much the same sort of way. Not only for weeks together, not only for months together, but even sometimes for years together, or at least, what seems like years together, just doing the same sort of things in the same sort of way. Of course if we reflect, we know that this is not really the case. We may in literal fact wash the very same identical dishes every day of the week, but we don't wash them in exactly the same way every day. We don't wash them in exactly the same sort of mood. We don't wash them under exactly the same sort of circumstances. One day, when we're washing them at the familiar kitchen sink, there may be sunlight streaming in at the open window. -

AA09-Patthana-24-Kondisi-2018.Pdf

| PAṬ Ṭ HA NA 24 Kondisi | 1 二十缘发趣论 PAṬṬHĀNA 24 Kondisi Sayalay Susıl̄ ā Dhammavihārı ̄ Buddhist Studies Jakarta 2018 2 | PAṬ Ṭ HA NA 24 Kondisi | Paramatthadesanā PAṬṬHĀNA 24 Kondisi Pustaka Penerbit Dhammavihārī Buddhist Studies Cetakan I, Agustus 2018 Penerjemah: Rosalina Lin Penyunting: Feronica Laksana Tabel: Pranoto Djojohadikoesoemo Design Sampul: Andries M. Halim Penata Letak & Grafik: Ary Wibowo Hak Cipta: Yayasan Dhammavihari Rukan Sedayu Square Blok N 15-19 Jl. Outer Ring Road, Lingkar Luar Jakarta Barat 11730 Tel: 0857 82 800 200 Email: [email protected] Website: www.dhammavihari.or.id Hak Cipta dilindungi oleh undang-undang. Buku ini dipublikasikan hanya untuk dibagikan secara GRATIS dan TIDAK UNTUK DIJUAL. PAṬṬHĀNA 24 Kondisi | PAṬ Ṭ HA NA 24 Kondisi | 31 Daftar Isi Kata Pengantar 5 Pendahuluan 7 I. Kondisi Akar (hetupaccayo) 17 II. Kondisi Objek (ārammaṇapaccayo) 31 III. Kondisi Yang-Mendominasi (adhipatipaccayo) 43 IV. Kondisi Tanpa-Antara (anantarapaccayo) 63 V. Kondisi Rangkaian (samanantarapaccayo) 67 VI. Kondisi Kemunculan-Bersama (sahajātapaccayo) 69 VII. Kondisi Mutualisme (aññamaññapaccayo) 75 VIII. Kondisi Ketergantungan (nissayapaccayo) 77 IX. Kondisi Ketergantungan-Yang-Kuat (upanissayapaccayo) 83 X. Kondisi Kemunculan-Lebih-Awal (purejātapaccayo) 99 XI. Kondisi Kemunculan-Belakangan (pacchājātapaccayo) 107 XII. Kondisi Pengulangan (āsevanapaccayo) 111 XIII. Kondisi Kamma (kammapaccayo) 119 XIV. Kondisi Resultan (vipākapaccayo) 139 XV. Kondisi Nutrisi (āhārapaccayo) 149 XVI. Kondisi Pengendalian (indriyapaccayo) -

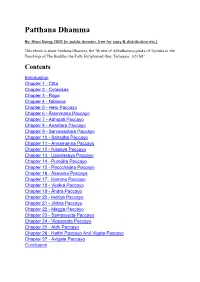

Patthana Dhamma

Patthana Dhamma By: Htoo Naing,2005 (in public domain, free for copy & distribution etc.) This ebook is about Patthana Dhamma, the 7th text of Abhidhamma pitaka of Tipitaka or the Teachings of The Buddha, the Fully Enlightened One, Tathagata, 623 BC. Contents Introduction Chapter 1 - Citta Chapter 2 - Cetasikas Chapter 3 - Rūpa Chapter 4 - Nibbana Chapter 5 - Hetu Paccayo Chapter 6 - Ārammana Paccayo Chapter 7 - Adhipati Paccayo Chapter 8 - Anantara Paccayo Chapter 9 - Samanantara Paccayo Chapter 10 - Sahajāta Paccayo Chapter 11 - Annamanna Paccayo Chapter 12 - Nissaya Paccayo Chapter 13 - Upanissaya Paccayo Chapter 14 - Purejāta Paccayo Chapter 15 - Paccchājāta Paccayo Chapter 16 - Āsevana Paccaya Chapter 17 - Kamma Paccayo Chapter 18 - Vipāka Paccayo Chapter 19 - Āhāra Paccayo Chapter 20 - Indriya Paccayo Chapter 21 - Jhāna Paccayo Chapter 22 - Magga Paccayo Chapter 23 - Sampayutta Paccayo Chapter 24 - Vippayutta Paccayo Chapter 25 - Atthi Paccayo Chapter 26 - Natthi Paccayo And Vigata Paccayo Chapter 27 - Avigata Paccayo Conclusion Introduction We are in this world. We can sense the world through our five senses. This is fact and not of anyone opinion. We have been in this world since we were born. And we will still be living in this world as long as our chance allows us to live. And we will definitely be leaving this world no doubt. The whole matter is clear and there is nothing to argue on this proposition. As we have been living, there were many many people who had lived in this world on this earth. When they were living they were striving for__ their lives and their continuing existence. Some merely did for their sake. -

Cosmology and Cultural Ecology As Reflected in Borobudur Buddhist Temple

Cosmology and Cultural Ecology as Reflected in Borobudur Buddhist Temple Dr.IdaBagus Putu Suamba1 Lecturer, Politeknik Negeri Bali, Indonesia Abstract Advancement in science and technology that has been achieved by human beings does not necessarily imply they are freed from environ- mental problems. Buddhism since the very beginning has been in harmony with nature; the Buddha was fond of nature; however, it is very little its sources speak about the interconnection between human and environment. The question of the significance of cultural ecology comes into promi- nent in these days as there has been increasing environmental problems happen. Borobudur Buddhist temple in Central Java contains some ideas or elements that can be used to cope with the problems mentioned. Interest- ingly, the whole body of the monument was inspired by the teachings of the Buddha and Buddhism in which the Causal Law having impetus in the theory dependent-origination (Pratyasamutpada) is reflected clearly in the reliefs of Mahakarmavibanggain Kamadhatubase level. For a better understanding of this law, the connection with cosmology in Mahayana Buddhism is discussed in brief. It is found that there are various natural elements were depicted and crafted by the artists in a high standard of art as the manifestations of the Buddha’s teachings. Amongst the natural elements depicted here, tree, plant, or forest are dominant elements, which appear almost in all reliefs either in the main walls or balustrade. The relatedness amongst the elements is shown beautifully in complex relationship amongst them, and this has moral, aesthetical, spiritual, and ecological messages that need to be known for spiritual as cendance.