Recent Desiccation-Related Ecosystem Changes at Lake Abert, Oregon: a Terminal Alkaline Salt Lake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mineral Resources of the Abert Rim Wilderness Study Area, Lake County, Oregon

Mineral Resources of the Abert Rim Wilderness Study Area, Lake County, Oregon U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1738-C AVAILABILITY OF BOOKS AND MAPS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Instructions on ordering publications of the U.S. Geological Survey, along with prices of the last offerings, are given in the cur rent-year issues of the monthly catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey." Prices of available U.S. Geological Sur vey publications released prior to the current year are listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" Publications that are listed in various U.S. Geological Survey catalogs (see back inside cover) but not listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" are no longer available. Prices of reports released to the open files are given in the listing "U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Reports," updated month ly, which is for sale in microfiche from the U.S. Geological Survey, Books and Open-File Reports Section, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225. Reports released through the NTIS may be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, Springfield, VA 22161; please include NTIS report number with inquiry. Order U.S. Geological Survey publications by mail or over the counter from the offices given below. BY MAIL OVER THE COUNTER Books Books Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water-Supply Papers, Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations, Circulars, publications of general in Books of the U.S. Geological Survey are available over the terest (such as leaflets, pamphlets, booklets), single copies of Earthquakes counter at the following Geological Survey Public Inquiries Offices, all & Volcanoes, Preliminary Determination of Epicenters, and some mis of which are authorized agents of the Superintendent of Documents: cellaneous reports, including some of the foregoing series that have gone out of print at the Superintendent of Documents, are obtainable by mail from WASHINGTON, D.C.-Main Interior Bldg. -

Lower Sycan Watershed Analysis

Lower Sycan Watershed Analysis Fremont-Winema National Forest 2005 Lower Sycan River T33S,R12E,S23 Lower Sycan Watershed Analysis Table of Contents INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................... 1 General Watershed Area.....................................................................................................................................2 Geology and Soils.................................................................................................................................................5 Climate..................................................................................................................................................................6 STEP 1. CHARACTERIZATION OF THE WATERSHED ................................................................... 7 I. Watershed and Aquatics.................................................................................................................................7 Soils And Geomorphology...............................................................................................................................................10 Aquatic Habitat ................................................................................................................................................................10 II. Vegetation.....................................................................................................................................................12 -

Lake Wise May 2021

May 2021 Lake Wise Page 1 LAKE WISE … a voice for quiet waters NEWSLETTER FROM OREGON LAKES ASSOCIATION MAY 2021 Annual Conference Sessions Connie Bozarth, Newsletter Manager Remote 1.5 to 2 hr Sessions IN THIS ISSUE Annual Conference of the Oregon Lakes Association (OLA) 2021 OLA Conference October/November October/November TBD (topics and dates to be determined) 2021 Scholarship Recipient Jamila Baig, UO Harmful Algae Blooms (HABS) Corner CyanoHABs outlook for Oregon CyanoHAB legislative action in Salem HABs research Careers in Freshwater Panel Recap Investigations of the Lower Deschutes Effect of Selective Water Withdrawal Structure on Water Quality Downstream of Lakes Billy Chinook and Simtustus Because of lingering uncertainties caused by the coronavirus pandemic and some advantages of short remote sessions spread Oregon Lakes in the News across several days, we will hold conference sessions using the same Drought Declared in Klamath Basin format as last year: connection via Zoom, with several 1.5 to 2 hr Camping to Open at Detroit Lake midweek sessions across October and November, avoiding the dates Keep an Eye on Fishing Gear! of face-to-face meetings that are being sponsored by WALPA (20-22 October) and NALMS (25-18 November). Drought Impacts-Spring 2021 Lake Abert and Upper Klamath Look for an invitation to submit abstracts soon, and a program Lake and registration info later! Forthcoming details on the conference event website May 2021 Lake Wise Page 2 2021 Oregon Lakes Association (OLA) Graduate Student Scholarship Recipient Contributed by Rich Miller, OLA Board Director OLA Awards 2021 Graduate Student Scholarship to Jamila Baig Oregon Lakes Association is pleased to award this year’s $1500 research scholarship to Jamila Baig, PhD candidate in the Environmental Sciences, Studies, and Policy and Geography Departments at University of Oregon. -

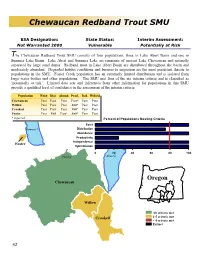

Chewaucan Redband Trout SMU

Chewaucan Redband Trout SMU ESA Designation: State Status: Interim Assessment: Not Warranted 2000 Vulnerable Potentially at Risk The Chewaucan Redband Trout SMU consists of four populations, three in Lake Abert Basin and one in Summer Lake Basin. Lake Abert and Summer Lake are remnants of ancient Lake Chewaucan and naturally separated by large sand dunes. Redband trout in Lake Abert Basin are distributed throughout the basin and moderately abundant. Degraded habitat conditions and barriers to migration are the most persistent threats to populations in the SMU. Foster Creek population has an extremely limited distribution and is isolated from large water bodies and other populations. The SMU met four of the six interim criteria and is classified as ‘potentially at risk’. Limited data sets and inferences from other information for populations in this SMU provide a qualified level of confidence in the assessment of the interim criteria. Population Exist Dist. Abund. Prod. Ind. Hybrid Chewaucan Pass Pass Pass Pass* Pass Pass Willow Pass Pass Pass Fail* Pass Pass Crooked Pass Pass Pass Fail* Pass Pass Foster Pass Fail Pass* Fail* Pass Pass * Inferred Percent of Populations Meeting Criteria Exist Summer L. Distribution Abundance Productivity Independence Foster Hybridization 0 20406080100 Paisley") Abert L. Oregon Chewaucan Willow All criteria met Crooked 4-5 criteria met < 4 criteria met Extinct 92 2 Distribution - Fail Abundance - Pass 100 Total Great Basin 80 Chew aucan 60 40 20 % ofPopulations 0 <0.06 0.06-0.19 >0.19 Density of age 1+ Redband Trout (fish/m2) Redband Major Rivers • Year-around distribution is widespread in headwater • A population survey estimated 147,878 (95%CI +/- and mid order streams. -

Quaternary Studies Near Summer Lake, Oregon Friends of the Pleistocene Ninth Annual Pacific Northwest Cell Field Trip September 28-30, 2001

Quaternary Studies near Summer Lake, Oregon Friends of the Pleistocene Ninth Annual Pacific Northwest Cell Field Trip September 28-30, 2001 springs, bars, bays, shorelines, fault, dunes, etc. volcanic ashes and lake-level proxies in lake sediments N Ana River Fault N Paisley Caves Pluvial Lake Chewaucan Slide Mountain pluvial shorelines Quaternary Studies near Summer Lake, Oregon Friends of the Pleistocene Ninth Annual Pacific Northwest Cell Field Trip September 28-30, 2001 Rob Negrini, Silvio Pezzopane and Tom Badger, Editors Trip Leaders Rob Negrini, California State University, Bakersfield, CA Silvio Pezzopane, United States Geological Survey, Denver, CO Rob Langridge, Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, Lower Hutt, New Zealand Ray Weldon, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR Marty St. Louis, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Summer Lake, Oregon Daniel Erbes, Bureau of Land Management, Carson City, Nevada Glenn Berger, Desert Research Institute, University of Nevada, Reno, NV Manuel Palacios-Fest, Terra Nostra Earth Sciences Research, Tucson, Arizona Peter Wigand, California State University, Bakersfield, CA Nick Foit, Washington State University, Pullman, WA Steve Kuehn, Washington State University, Pullman, WA Andrei Sarna-Wojcicki, United States Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA Cynthia Gardner, USGS, Cascades Volcano Observatory, Vancouver, WA Rick Conrey, Washington State University, Pullman, WA Duane Champion, United States Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA Michael Qulliam, California State University, Bakersfield, -

Abert and Summer Lakes, South-Central Oregon

... ( t.• CE'...,.. ~ - ~'>01..1.4_... ~ Dl - . ,, c E: 70. I V F' O I 12 "7.'t: I z Solute Balance at 'i.'] .J Abert and Summer Lakes, South-Central Oregon GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 502-C Solute Balance at Abert and Summer Lakes, South-Central Oregon By A. S. VAN DENBURGH CLOSED- BASIN INVESTIGATIONS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 502-C A description of the quantity and chemical character of incoming, outgoing, and stored solutes and the mechanisms of solute accumulation and depletion in a saline environment UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 1975 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data VanDenburgh, A. S. Solute balance at Abert and Summer Lakes, south-central Oregon. (Closed-basin investigations) (Geological Survey Professional Paper 502-C) Bibliography: p. Supt. of Docs. No.: I 19.16:502-C 1. Saline waters-Oregon-Abert Lake. 2. Saline waters-Oregon-Summer Lake. I. Title. II. Series. III. Series: United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 502-C. QE75.P9 No. 502-C fGB1625.07) 557.3'08s f553'.72'0979593) 75-619062 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Stock Number 024-001-02689-9 CONTENTS P.1ge Page Abstract ... ..... ........ ....... .. .... ..... .. ....... ........ ........ ... .. ... ... ... ... ... .. C1 Solute bala!H"e ................................................................................... C10 Introduction .................................................................................... -

Eastside Chapter 2 Affected Environment

Eastside Chapter 2 Affected Environment Contents Purpose and Organization of This Chapter ........................................................................................................... 1 Historical Conditions ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Positive Ecological Trends............................................................................................................................. 4 Ecological Reporting Units, Hydrologic Unit Codes, and Clusters................................................................. 6 Humans and Land Management: Snapshots in Time .................................................................................. 10 Physical Environment ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Geology and Physiography........................................................................................................................... 15 Soils and Soil Productivity .......................................................................................................................... 18 Climate ..................................................................................................................................................... 23 Air Quality ................................................................................................................................................ -

Goose and Summer Lakes Basin Report

GOOSE AND SUMMER LAKES BASIN REPORT. State of Oregon WATER RESOURCES DEPARTMENT Salem, Oregon May 1989 WILLIAM H. YOUNG, DIRECTOR WATER RESOURCES COMMISSION Members: WILLIAM R. BLOSSER. CHAIRMAN HADLEY AKINS CLIFF BENTZ CLAUDE CURRAN JAMES HOWLAND DEIRDRE MALARKEY LORNA STICKEL TABLE OF CONTENTS IN1RODUCTION........................................................................................................... v A. Purpose of Report.......................................................................................... v B. Planning Process ............................................................................................ v C. Report Organization .... .... .... .................... .. ...... ...... ...... ...................... .... ....... vi SECTION 1. GOOSE AND SUMMER LAKES BASIN OVERVIEW....................... 1 A. Physical Description...................................................................................... 1 B. Cultural Description ...................................................................................... 9 C. Resources...................................................................................................... 12 D. Water Use and Control ................................................................................. 15 SECTION 2. THOMAS CREEK .................................................................................. 23 A. Issue.............................................................................................................. 23 B. Background.................................................................................................. -

Groundwater Compliance Action Plan for the Lakeview, Oregon, Processing Site

LMS/LKP/S06182 Groundwater Compliance Action Plan for the Lakeview, Oregon, Processing Site June 2010 This page intentionally left blank LMS/LKP/S06182 Groundwater Compliance Action Plan for the Lakeview, Oregon, Processing Site June 2010 This page intentionally left blank Contents Abbreviations................................................................................................................................. iii 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................1–1 1.1 Previous Site Documentation ...................................................................................1–1 1.2 Regulatory Framework .............................................................................................1–1 1.3 Groundwater Compliance Status ..............................................................................1–2 2.0 Site Information..................................................................................................................2–1 2.1 Location ....................................................................................................................2–1 2.2 Remedial Action History and Current Land Status ..................................................2–1 2.3 Site Characteristics ...................................................................................................2–1 2.3.1 Climate...........................................................................................................2–1 2.3.2 -

Lake Abert Northwest OR-015-097

Year: 2018 Inventory Unit Number/Name: OR-015-097/ Lake Abert Northwest FORM 1 DOCUMENTATION OF BLM WILDERNESS INVENTORY FINDINGS ON RECORD 1. Is there existing BLM wilderness inventory information on all or part of this area? No Yes ___X____ (if more than one unit is within the area, list the names/numbers of those units): a) Inventory Source: a. Wilderness – Proposed Initial Inventory: Roadless Areas and Islands Which Clearly Do Not Have Wilderness Characteristics; USDI BLM - Oregon and Washington, April 1979. b. Wilderness Review – Initial Inventory: Final Decision on Public Lands Obviously Lacking Wilderness Characteristics and Announcement of Public Lands to be Intensively Inventoried for Wilderness Characteristics; USDI BLM - Oregon and Washington, August 1979. b) Inventory Unit Number(s)/Name(s): 1-97 c) Map Name(s)/Number(s): Wilderness Review – Initial Inventory: Final Decision on Public Lands Obviously Lacking Wilderness Characteristics and Announcement of Public Lands to be Intensively Inventoried for Wilderness Characteristics; USDI BLM - Oregon and Washington, August 1979. d) BLM District(s)/Field Office(s): Lakeview District, Lakeview Resource Area. 2. BLM Inventory Findings on Record: Existing inventory information regarding wilderness characteristics (if more than one BLM inventory unit is associated with the area, list each unit and answer each question individually for each inventory unit): Unit# Size Natural Outstanding Outstanding Supplemental (historic Condition? Solitude? Primitive & Values? acres) Y/N Y/N Unconfined Y/N Recreation? Y/N 1-97 16,800 N N N N/A 1-97* 18,555 N N/A N/A N/A *The inventory of this unit was updated in 2012. -

Signature Redacted for Privacy. Abstract Approved: Robert Kf

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Kathryn M. Boula for the degree of Master of Science in the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife presented on October31, 1986 Title: Foraging Ecolo of Migrant Wa-birds, Lake Abert, Oregon Signature redacted for privacy. Abstract approved: Robert kf. 4larvis Seven species of water-dependent birds (northern phalarope, Phalaropus lobatus; American avocet, Recurvirostra americana;Wilson's phalarope, P. tricolor; eared grebe, Podiceps nigricollis; ring-billed gull Larus delawarensis; California gull, L. californicus; and northern shoveler, Anas clypeata) were studied during the fall migrations of 1982 and 1983 to determine the dietsand foraging strategies of mixed-species feeding assemblages at an alkaline lake in southcentral Oregon. Information on density and distribution of birds and their prey resources was collected at permanent sampling points along the eastern shore of LakeAbert, Lake Co., OR. Determination of diet composition was based on analysis of stomach samples from collected specimens. Between-species comparisons of diet composition were made using classification analyses. Diet samples were compared to prey availability samples to discernwhether birds fed preferentially on particular prey types. Timed observations were used to develop time budgets.Multivariate ordination procedures were used to determine the extent of niche overlapand resource partitioning. Structural measurements were taken from collected specimens to aid in assessment of physiological conditionof migrants. Total numbers of migrants using Lake Abert varied from year to year. Numbers of all species except eared grebes and gulls were lower in 1983 than in 1982. Total sample biomass of prey also declined between 1982 and 1983. Fifteen potential prey types were identified within the lake and along the lakeshore. -

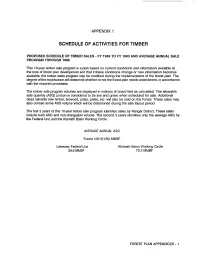

Schedule of Activities for Timber

APPENDIX 1 SCHEDULE OF ACTIVITIES FOR TIMBER PROPOSED SCHEDULE OF TIMBER SALES - FY 1989 TO FY 1993 AND AVERAGE ANNUAL SALE PROGRAM THROUGH 1998 This IO-year timber sale program is a plan based on current conditions and information available at the time of forest plan development and that if these conditions change or new information becomes available, the timber sales program may be modified during the implementation of the forest plan The degree of the modificationwill determine whether or not the forest plan needs amendment, in accordance with the required processes. The timber sale program volumes are displayed in millions of board feet as calculated The allowable sale quantity (ASQ) portion is considered to be live and green when scheduled for sale Additional dead salvable saw timber, firewood, posts, poles, etc will also be sold on the Forest These sales may also contain some ASQ volume which will be determined during the sale layout period The first 5 years of this IO-year timber sale program identifies sales by Ranger District. These sales include both ASQ and non-chargeable volume The second 5 years identifies only the average ASQ by the Federal Unit and the Klamath Basin Working Circle AVERAGE ANNUAL ASQ Forest 135 9(136) MMBF Lakeview Federal Unit Klamath Basin Working Circle 59.6 MMBF 76 3 MMBF FOREST PIAN APPENDICES - 1 TEN - YEAR TIMBER SALE SCHEDULE Timber Harvest Volume Distribution, FY 1989 Lakevlew Federal Sustained Yield Unit Klamath Basin Working Circle (Forest Portlon) Sale Name Location Mgt Volume Road Miles121 Sale Name Location Mgt Volume Road Milesn Areail) (MMBF) C R Area(t) (MMBF) C R Bly Ranger District Spodueia] TMS,R12E.