PDF Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free Download

ORSBORNAGAIN a new look at old songs of new life by Rob Birks ORSBORNAGAIN Rob Birks 2013 Frontier Press All rights reserved. Except for fair dealing permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any means without written permission from the publisher. Birks, Rob ORSBORNAGAIN May 2013 Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture references used in this text are from The Holy Bible, New International Version. THE HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. The King James Version is public domain in the United States. Scripture taken from The Message. Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 2000, 2001, 2002. Used by permission of NavPress Publishing Group. Copyright © The Salvation Army USA Western Territory ISBN 978-0-9768465-8-1 Printed in the United States For my mother, Major Ruth Birks, who always hummed a tune as I was growing up, and who is herself one of God’s great poetic works & my Poet Father, Major Daniel H. Birks— always reading, always writing, always loving. iii Rob Birks has fittingly honored the enduring legacy of Albert Ors- born’s poetic brilliance, bringing the Salvation Army General’s timeless language into a modern context and adding commentary reflecting Birks’ own inimitable personality. I was blessed by this book, strength- ened and challenged in the reading to be a blessing to OTHERS. —Tom Walker, Social Services Secretary The Salvation Army Northwest Division A living faith will find its voice in contemporary idiom. We rightly em- brace in our worship ever fresh expressions of Spirit-inspired praise. -

SONGBOOK Mulligans

PUB SONGS DAMIEN (26.11.2017) Cliquez sur un titre pour voir les paroles A-HA …………….………………... Hunting high and low Take on me ADELE ……………….…………… Rolling in the deep Send my love (to your new lover) ALAIN BASHUNG ………….…. La nuit je mens Madame rêve ALANIS MORISSETTE ……… Hand in my pocket Ironic Uninvited You learn You oughta know ALEX CLARE ……………..….…. Too close ALICIA KEYS ……………..…..… If I ain't got you ALT J ……………….………..…….. Breezeblocks AMY WINEHOUSE …………… Back to black Valerie You know I'm no good ANDY GRAMMER …………….. Keep your head up ANGUS & JULIA STONE ……. Big jet plane ARCTIC MONKEYS ………...… Fluorescent adolescent When the sun goes down ARIANE MOFFATT …………… Je veux tout AS ANIMALS ……………………. Ghost gunfighters AUDIOSLAVE ………………...… Cochise AVRIL LAVIGNE …………...….. Complicated I'm with you Sk8er Boi AXEL BAUER & ZAZIE ……..... A ma place BEYONCÉ …………………….….. Halo Runnin' (Lose It All) BJÖRK ……………………….....…. Bachelorette BLINK-182 ………..………......… All the small things I miss you BLUR ………………………………. Charmless man BOY ……………………………….... Little numbers BRITNEY SPEARS ……….……. Baby one more time Toxic Womanizer BRUNO MARS ………..………… When I was your man CALI ………………………….…….. Elle m'a dit CARLY RAE JEPSEN …………. Call me maybe CEE-LO GREEN …….………..… Fuck you CHARLIE WINSTON …………. In your hands Like a hobo CHRIS ISAAK ………………….... Wicked game CHRISTINA AGUILERA …….. Beautiful CHUCK BERRY ……………..….. You never can tell COCOON ………………………..... Chupee Comets On my way COLBIE CAILLAT ....………..… Bubbly COLD WAR KIDS …………...… Hang me up to dry We used to vacation COLDPLAY …………..………..… Clocks Fix you God put a smile upon your face Green eyes In my place Magic Speed of sound The scientist Trouble What if Yellow COLDPLAY FT. BEYONCE ... Hymn for the weekend COLPLAY FT. -

Ecad Setembro 2020

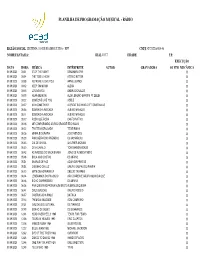

PLANILHA DE PROGRAMAÇÃO MUSICAL - RÁDIO RAZÃO SOCIAL: SISTEMA 103 DE RADIOS LTDA - EPP CNPJ: 82721226000146 NOME FANTASIA: DIAL: 103.7 CIDADE: UF: EXECUÇÃO DATA HORA MÚSICA INTÉRPRETE AUTOR GRAVADORA AO VIVO MECÂNICA 01/09/2020 00:01 STAY THE NIGHT BENJAMIM ORR X 01/09/2020 00:04 THE TIDE IS HIGH ATOMIC KITTEN X 01/09/2020 00:08 NO MORE I LOVE YOU ANNIE LENNOX X 01/09/2020 00:12 KEEP ON MOVIN ALEXIA X 01/09/2020 00:15 LOVING YOU ANDRU DONALDS X 01/09/2020 00:19 HEAR ME NOW ALOK, BRUNO MARTINI FT ZEEBA X 01/09/2020 00:22 SOMEONE LIKE YOU ADELE X 01/09/2020 00:27 SAY SOMETHING A GREAT BIG WORLD FT CRISTINA AGUILERA X 01/09/2020 05:08 BOMBACHA RISCADA ALBINO MANIQUE X 01/09/2020 05:11 BOMBACHA RISCADA ALBINO MANIQUE X 01/09/2020 05:12 RODA QUE RODA CANTO NATIVO X 01/09/2020 05:18 ME COMPARANDO AO RIO GRANDE IEDO SILVA X 01/09/2020 05:22 TRISTE MADRUGADA TEIXEIRINHA X 01/09/2020 05:26 MINHA BIOGRAFIA JOSE MENDES X 01/09/2020 05:29 RANCHEIRA DAS PRENDAS OS MONARCAS X 01/09/2020 05:35 DIA DE CHUVA WALTHER MORAIS X 01/09/2020 05:40 DE A CAVALO TCHE BARBARIDADE X 01/09/2020 05:43 AS RAZOES DO BACA BRABA JOAO DE ALMEIDA NETO X 01/09/2020 05:48 BOLA NAS COSTAS OS MIRINS X 01/09/2020 05:51 SEARAS DE PAZ ADAIR DE FREITAS X 01/09/2020 05:54 CAMINHO DE LUZ GRUPO GALPAO DO PAMPA X 01/09/2020 06:10 MATE DE ESPERANCA DELCIO TAVARES X 01/09/2020 06:14 LEMBRANCA DO PASSADO ARI CORREIA E GRUPO ALMA DA QUERENCIA X 01/09/2020 06:18 BICHO CARPINTEIRO OS MIRINS X 01/09/2020 06:28 PRA QUEM FAZ PATRIA NUM BASTO ALMA MUSIQUEIRA X 01/09/2020 06:41 DEUS GAUCHO GRUPO -

Table-Talk, Essays on Men and Manners by William Hazlitt</H1>

Table-Talk, Essays on Men and Manners by William Hazlitt Table-Talk, Essays on Men and Manners by William Hazlitt TABLE-TALK ESSAYS ON MEN AND MANNERS by WILLIAM HAZLITT CONTENTS VOLUME I 1. On the Pleasure of Painting 2. The Same Subject Continued 3. On the Past and Future 4. On Genius and Common Sense 5. The Same Subject Continued 6. Character of Cobbett 7. On People With One Idea 8. On the Ignorance of the Learned 9. The Indian Jugglers page 1 / 529 10. On Living To One's-Self 11. On Thought and Action 12. On Will-Making 13. On Certain Inconsistencies In Sir Joshua Reynolds's Discourses 14. The Same Subject Continued 15. On Paradox and Common-Place 16. On Vulgarity and Affectation VOLUME II 1. On a Landscape of Nicholas Poussin 2. On Milton's Sonnets 3. On Going a Journey 4. On Coffee-House Politicians 5. On the Aristocracy of Letters 6. On Criticism 7. On Great and Little Things 8. On Familiar Style 9. On Effeminacy of Character 10. Why Distant Objects Please 11. On Corporate Bodies 12. Whether Actors Ought To Sit in the Boxes 13. On the Disadvantages of Intellectual Superiority 14. On Patronage and Puffing 15. On the Knowledge of Character 16. On the Picturesque and Ideal 17. On the Fear of Death page 2 / 529 VOLUME I ESSAY I ON THE PLEASURE OF PAINTING 'There is a pleasure in painting which none but painters know.' In writing, you have to contend with the world; in painting, you have only to carry on a friendly strife with Nature. -

NA-D Kodulehel.Xlsx

Esitaja Pealkiri Laurent Couson [ SACEM ]Publishers Magical Child "A Wedding March...sort of.... " "A Wedding March...sort of.... " "Boog-it" Jonathan Stout featuring Laura Windley "Cry Me A River Matthew Stone "Lullaby" (Aviva's And Henrietta's Theme Nathan Larson & Nina Persson (Saint Motel) -Sax Cover Daniele Vitale My Type [Ex] da Bass & IAN BREARLEY HOLD ON [EX] DA BASS [+] JANA KASK LIKE A MELODY [Yakut Sakha-Turks] Juliana (Юлияна) Uhuktuu (Уhуктуу) ☓i∪s ¬iИк x VΛVILONΞC Не хочу •You Know You Know Little Willie 1 Awake 1 Dads Return To 115 Hangover 11-59 The Railers 12 EEK Monkey ja Põhja Konn Muusikaline intro KR tunnusmuusika põhjal 148 Debüüt Wash 158 14 Of monster and men Little talks (the knocks remix) 18 Mne Uze Ruki Verh 18 Берез Чиж 1Step4Dub & Awe Las Ma Laulan 1Step4Dub & Awe Sina 1teist €¥¥ 1Teist Feat. Sammalhabe Paduvihm 2 03 Various Artists Javanese Suite 2 Chainz Diamonds Talkin’ Back 2014 Gimn Cosi 25Band Enghad Bekhand 2Kõik Kõik Boyz 2U Sind Vaid Sind 30 Second Timer With Jeopardy Thinking Music 31 Second Timer With Jeopardy Thinking Music 3Pead Armastuse Valgus 3Pead Elame Edasi 3Pead Keelatud Vili 3Pead Paneme Leekima 3Pead Poolel Teel 3Pead Poolel Teel 2013 3Pead Soovide Puu 3Pead Transmitter 3Pead Tuuletõmme 3Pead Uned 3Pead & Bonzo Prostituudi Laul 3Peat Cosmastly 3TM Memory 4 2 Go Bemmi Kummid 4 2 Go Sidur Pidur Gaas Gaas 4 Ever Loetud Päevad 4 Ever Oled Osa Minust 4 Non Blondes l What's Up 42 Go Bemmi Kummid 42 Go Bemmi Kummid (Cheesemaster 5000 Remix) 42Go Feat. More 2 Come Papahh Papahh 4Pead Lillelaps 4Visioon Et Sa Ei Kaoks 4Visioon Feat. -

Ecad Novembro 2020

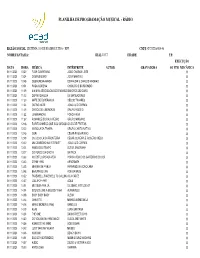

PLANILHA DE PROGRAMAÇÃO MUSICAL - RÁDIO RAZÃO SOCIAL: SISTEMA 103 DE RADIOS LTDA - EPP CNPJ: 82721226000146 NOME FANTASIA: DIAL: 103.7 CIDADE: UF: EXECUÇÃO DATA HORA MÚSICA INTÉRPRETE AUTOR GRAVADORA AO VIVO MECÂNICA 01/11/2020 10:20 FLOR CAMPESINA JOAO CHAGAS LEITE X 01/11/2020 10:24 DOMINGUEIRO JOCA MARTINS X 01/11/2020 10:48 QUERENCIA AMADA OSWALDIR E CARLOS MAGRAO X 01/11/2020 10:51 RODA MORENA CHIQUITO E BORDONEIO X 01/11/2020 11:09 A M M M ASSOCIACAO DOS MARIDOSGAROTOS MANDADO DE PELAS OURO MUIE X 01/11/2020 11:13 DEPOIS DA LIDA OS MATEADORES X 01/11/2020 11:30 MATE DE ESPERANCA DELCIO TAVARES X 01/11/2020 11:34 OUTRO MATE JOAO LUIZ CORREA X 01/11/2020 11:49 GRITOS DE LIBERDADE GRUPO RODEIO X 01/11/2020 11:53 LEMBRANCAS PORCA VEIA X 01/11/2020 11:57 ROMANCE DO PALA VELHO GRUPO MINUANO X 01/11/2020 12:16 EU RECONHECO QUE SOU GROSSO GILDO DE FREITAS X 01/11/2020 12:22 NA BOCA DA TRAIRA GRUPO CANTO NATIVO X 01/11/2020 12:45 GURI CESAR PASSARINHO X 01/11/2020 12:49 OS LOCO LA DA FRONTEIRA CESAR OLIVEIRA E ROGERIO MELO X 01/11/2020 13:02 UM CAMBICHO NA INTERNET JOAO LUIZ CORREA X 01/11/2020 13:24 AMIGOS DO TEMPO ELTON SALDANHA X 01/11/2020 13:27 DO FUNDO DA GROTA BAITACA X 01/11/2020 13:33 NO ESTILO PORCA VEIA PORCA VEIA E OS GAITEIROS DO CORDIONA X 01/11/2020 13:40 CRYIN' 1993 AEROSMITH X 01/11/2020 13:45 MENINA DE FIVELA FERNANDO E SOROCABA X 01/11/2020 13:48 BEAUTIFUL LIFE ACE OF BASE X 01/11/2020 13:52 FAREWELL, FAREWELL TO CALLINGFORDA LA CARTE 1980 X 01/11/2020 13:57 LOLLIPOP 1997 AQUA X 01/11/2020 14:01 ME DEIXA PRA LÁ DILSINHO, -

Redox DAS Artist List for Period: 01.06.2017

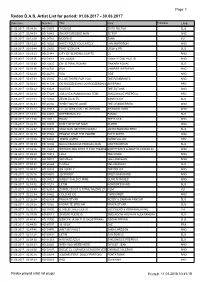

Page: 1 Redox D.A.S. Artist List for period: 01.06.2017 - 30.06.2017 Date time: Number: Title: Artist: Publisher Lang: 01.06.2017 00:04:56 HD 59675 TI DEKLE ZVITA FELTNA SLO 01.06.2017 00:08:03 HD 36443 SHARP DRESSED MAN ZZ TOP ANG 01.06.2017 00:12:09 HD 24782 MODRICE ZANA YU 01.06.2017 00:15:22 HD 16522 HAVE I TOLD YOU LATELY VAN MORRISON ANG 01.06.2017 00:19:44 HD 23650 FANT IZ ZALIVA URSA & PR SLO 01.06.2017 00:23:23 HD 21947 CITY OF BLINDING LIGHTS U2 ANG 01.06.2017 00:29:06 HD 58641 THE JUDGE TWENTY ONE PILOTS ANG 01.06.2017 00:33:42 HD 12425 ON JE PISAL ROMAN TINKARA KOVAC SLO 01.06.2017 00:38:36 HD 44730 RUN VAMPIRE WEEKEND ANG 01.06.2017 00:42:28 HD 44281 YOU TIDE ANG 01.06.2017 00:47:01 HD 30105 I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU THE REMBRANTS ANG 01.06.2017 00:50:01 HD 31729 OD RODZENDANA DO RODZENDANASEVERINA HRV 01.06.2017 00:54:22 HD 30429 VALERIE THE ZUTONS ANG 01.06.2017 00:58:10 HD 57628 JOS UVEK POMISLIM NA TEBE ZAKLONISCE PREPEVA HRV 01.06.2017 01:01:31 HD 14803 ZELIM DA SI TU SANK ROCK SLO 01.06.2017 01:05:41 HD 23132 WHEN YOU'RE GONE THE CRANBERRIES ANG 01.06.2017 01:10:13 HD 29819 LITTLE MISS CAN'T BE WRONG SPIN DOCTORS ANG 01.06.2017 01:14:01 HD 49403 NEPREMAGLJIVI PANDA SLO 01.06.2017 01:17:50 HD 29812 ROAM THE B 52'S ANG 01.06.2017 01:22:35 HD 18699 DON'T STOP ME NOW QUEEN ANG 01.06.2017 01:26:07 HD 00995 VSAK DAN OB ISTEM SANKU JANEZ BONCINA BENC SLO 01.06.2017 01:30:15 HD 55744 PEOPLE HAVE THE POWER PATTI SMITH ANG 01.06.2017 01:35:09 HD 59800 JESEN U MENI PARNI VALJAK HRV 01.06.2017 01:39:33 HD 16504 NOCOJ BOMO MI PRIZGALI -

Redox DAS Artist List for Period: 01.05.2017

Page: 1 Redox D.A.S. Artist List for period: 01.05.2017 - 31.05.2017 Date time: Number: Title: Artist: Publisher Lang: 01.05.2017 13:48:38 HD 58072 A SI SPLOH TISTA CLEMENS SLO 01.05.2017 13:52:14 HD 59718 VASE POGLEJ D BASE SLO 01.05.2017 13:54:48 HD 60554 DON'T COME EASY (AVSTRALIJA) ISAIAH ANG 01.05.2017 13:57:50 HD 59891 LET'S HURT TONIGHT ONEREPUBLIC ANG 01.05.2017 14:04:11 HD 58704 REPEAT NEJC LOMBARDO SLO 01.05.2017 14:07:44 HD 59799 URA TECE NINA SLO 01.05.2017 14:10:50 HD 59875 ON WHAT YOU'RE ON BUSTED ANG 01.05.2017 14:20:34 HD 59930 PAZI DA BO PRAV (LIFE IS WHAT YOUXEQUTIFZ MAKE IT) SLO 01.05.2017 14:24:40 HD 60370 PIECE BY PIECE (IDOL VERSION) KELLY CLARKSON ANG 01.05.2017 14:28:17 HD 59882 TRAIL OF BROKEN HEARTS JAMES BLUNT ANG 01.05.2017 14:32:34 HD 59886 CRINGE MATT MAESON ANG 01.05.2017 14:36:34 HD 59850 ROLLING STONE AIR DICE ANG 01.05.2017 14:39:34 HD 59654 RECI MI DA MANOUCHE SLO 01.05.2017 14:42:53 HD 59616 MOJA KITARA NEJC LOMBARDO SLO 01.05.2017 14:50:54 HD 59722 LOVE MY LIFE ROBBIE WILLIAMS ANG 01.05.2017 14:54:24 HD 59695 PRISONER IN PARADISE SUNRISE AVENUE ANG 01.05.2017 14:57:44 HD 59641 NO NO NO MILOW ANG 01.05.2017 15:04:43 HD 59601 DVA ZA MENE KATARINA MALA SLO 01.05.2017 15:08:16 HD 58936 TREAT YOU BETTER SHAWN MENDES ANG 01.05.2017 15:11:18 HD 60066 NAJINO SRCE URSKA SUBASIC SLO 01.05.2017 15:15:06 HD 58945 POZITIVEN SONG ANZHE SLO 01.05.2017 15:18:26 HD 59924 ZIVLJENJE DISI NULA KELVINA SLO 01.05.2017 15:22:27 HD 60513 ONLY YOU SELENA GOMEZ ANG 01.05.2017 15:26:44 HD 34205 CLOUD NUMBER NINE (RMX) BRYAN ADAMS ANG 01.05.2017 15:36:14 HD 60512 SIJAJ RAIVEN SLO 01.05.2017 15:42:13 HD 59326 THIS HOUSE IS NOT FOR SALE BON JOVI ANG 01.05.2017 15:49:50 HD 60394 ENCANTO (FEAT. -

Vrijwel Iedereen Heeft Wel Een Mening Over Afrojack. Deze Meningen Gaan Alle Kanten Op En Lijken Nogal Eens Geboren Te Zijn Uit Afgunst

INTERVIEW Vrijwel iedereen heeft wel een mening over Afrojack. Deze meningen gaan alle kanten op en lijken nogal eens geboren te zijn uit afgunst. Toch komen ze niet helemaal uit de lucht vallen, want Afrojack is succesvol en dan vellen mensen al gauw een oordeel over je. Feit is dat we hem gerust mogen rekenen tot de top 10 van exportproducten uit Nederland. Dit jaar eindigde hij bovendien op de tiende plaats van de lijst van meest populaire dj's, de DJ Top 100. We spraken uitgebreid met de dj en producer over zijn imago, veelzijdigheid en ambities, en over het begeleiden van jonge, talentvolle producers. TEKST PETER GÜLDENPFENNIG EN THOMAS KEULEMANS FOTOGRAFIE GERARD HENNINGER p de standaard openingsvraag hoe het met bling eromheen’, aldus Nick. We DOORBRAAK Afrojack gaat, glimlacht hij een beetje gelaten. hebben het over ‘de bladen’ en Afrojack beleefde ‘Goed, druk… maar druk is goed! Druk waarmee? de roddels omtrent het publieke zijn wereldwijde Op dit moment vooral met het afwerken van muziek die ik figuur Afrojack. Want hij kan nog dovorbraak met de track 'Take Over in L.A. heb opgenomen. Natuurlijk heb ik een druk leven, zoveel muziek maken, de media Control', samen met maar het is echt een kwestie van gewoon doen. Dingen focust toch vooral vaak op zijn (ex-) zangeres Eva Simons. regelen.’ vriendinnen, de nieuwste auto die Het nummer kwam uit hij heeft gekocht, of andere zaken in de zomer van 2010 en deed het niet alleen RANDZAKEN Op muzikaal vlak gaat het Afrojack, wiens die maar weinig met zijn muziek goed in Europa, maar echte naam Nick van de Wall is, behoorlijk voor de wind. -

510 Marc Cohn Walking in Memphis 1991 509 Dusty Springfield In

NR ARTIEST NUMMER JAAR 510 Marc Cohn Walking In Memphis 1991 509 Dusty Springfield In Private 1990 508 R. E. M. Shiny Happy People 1991 507 Donna Lewis I Love You Always Forever 1996 506 Zucchero Fornaciari & Paul Young Senza Una Donna 1991 505 Will Smith Miami 1998 504 Peter Andre Mysterious Girl 1996 503 Han Van Eijck Leef 'Big Brother Tune' 1999 502 Bob Marley Sun Is Shining 1999 501 Bon Jovi Always 1994 500 Swv Right Here 1993 499 Lois Lane Tonight 1994 498 Laura Pausini La Solitudine 1993 497 Edwyn Collins A Girl Like You 1994 496 Mariah Carey Emotions 1991 NR ARTIEST NUMMER 1 UNDERWORLD BORN SLIPPY 2 ROBIN S SHOW ME LOVE 3 JAYDEE PLASTIC DREAMS 4 DAFT PUNK ONE MORE TIME 5 SWEDISH HOUSE MAFIA ONE 6 KERNKRAFT 400 ZOMBIE NATION 7 DANNY TENAGLIA MUSIC IS THE ANSWER 8 AVICII LEVELS 9 MARTIN GARRIX ANIMALS WILDSTYLEZ FT. 10 NIELS GEUSEBROEK YEAR OF SUMMER 11 PAUL & FRITZ KALKBRENNER SKY AND SAND 12 RUNE CALABRIA 13 ENERGY 52 CAFE DEL MAR (THREE N ONE REMIX) 14 M.A.N.D.Y & BOOKA SHADE BODY LANGUAGE 15 MOTORCYCLE AS THE RUSH COMES 16 BRENNAN HEART & WILDSTYLEZ LOSE MY MIND 17 THE PRODIGY SMACK MY BITCH UP 18 SNAP! RHYTHM IS A DANCER 19 SAFRI DUO PLAYED-A-LIVE (THE BONGO SONG) 20 TIM BERG BROMANCE (AVICII MIX) 21 WILDCHILD RENEGADE MASTER 22 PAUL ELSTAK RAINBOW IN THE SKY 23 BOMFUNK MCS FREESTYLER 24 ROGER SANCHEZ ANOTHER CHANCE NR ARTIEST NUMMER 25 MR OIZO FLAT BEAT 26 TIËSTO TRAFFIC 27 CALVIN HARRIS SUMMER 28 IDA ENGBERG DISCO VOLANTE 29 DAVID GUETTA FT.