Computersacific 2008CIFIC Philosophical Universityuk Articles PHILOSOPHICAL Publishing of Quarterlysouthernltd QUARTERLY California and Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Computers" Abacus—The First Calculator

Component 4: Introduction to Information and Computer Science Unit 1: Basic Computing Concepts, Including History Lecture 4 BMI540/640 Week 1 This material was developed by Oregon Health & Science University, funded by the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology under Award Number IU24OC000015. The First "Computers" • The word "computer" was first recorded in 1613 • Referred to a person who performed calculations • Evidence of counting is traced to at least 35,000 BC Ishango Bone Tally Stick: Science Museum of Brussels Component 4/Unit 1-4 Health IT Workforce Curriculum 2 Version 2.0/Spring 2011 Abacus—The First Calculator • Invented by Babylonians in 2400 BC — many subsequent versions • Used for counting before there were written numbers • Still used today The Chinese Lee Abacus http://www.ee.ryerson.ca/~elf/abacus/ Component 4/Unit 1-4 Health IT Workforce Curriculum 3 Version 2.0/Spring 2011 1 Slide Rules John Napier William Oughtred • By the Middle Ages, number systems were developed • John Napier discovered/developed logarithms at the turn of the 17 th century • William Oughtred used logarithms to invent the slide rude in 1621 in England • Used for multiplication, division, logarithms, roots, trigonometric functions • Used until early 70s when electronic calculators became available Component 4/Unit 1-4 Health IT Workforce Curriculum 4 Version 2.0/Spring 2011 Mechanical Computers • Use mechanical parts to automate calculations • Limited operations • First one was the ancient Antikythera computer from 150 BC Used gears to calculate position of sun and moon Fragment of Antikythera mechanism Component 4/Unit 1-4 Health IT Workforce Curriculum 5 Version 2.0/Spring 2011 Leonardo da Vinci 1452-1519, Italy Leonardo da Vinci • Two notebooks discovered in 1967 showed drawings for a mechanical calculator • A replica was built soon after Leonardo da Vinci's notes and the replica The Controversial Replica of Leonardo da Vinci's Adding Machine . -

Programs Processing Programmable Calculator

IAEA-TECDOC-252 PROGRAMS PROCESSING RADIOIMMUNOASSAY PROGRAMMABLE CALCULATOR Off-Line Analysi f Countinso g Data from Standard Unknownd san s A TECHNICAL DOCUMENT ISSUEE TH Y DB INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, VIENNA, 1981 PROGRAM DATR SFO A PROCESSIN RADIOIMMUNOASSAN I G Y USIN HP-41E GTH C PROGRAMMABLE CALCULATOR IAEA, VIENNA, 1981 PrinteIAEe Austrin th i A y b d a September 1981 PLEASE BE AWARE THAT ALL OF THE MISSING PAGES IN THIS DOCUMENT WERE ORIGINALLY BLANK The IAEA does not maintain stocks of reports in this series. However, microfiche copies of these reports can be obtained from INIS Microfiche Clearinghouse International Atomic Energy Agency Wagramerstrasse 5 P.O.Bo0 x10 A-1400 Vienna, Austria on prepayment of Austrian Schillings 25.50 or against one IAEA microfiche service coupon to the value of US $2.00. PREFACE The Medical Applications Section of the International Atomic Energy Agenc s developeha y d severae th ln o programe us r fo s Hewlett-Packard HP-41C programmable calculator to facilitate better quality control in radioimmunoassay through improved data processing. The programs described in this document are designed for off-line analysis of counting data from standard and "unknown" specimens, i.e., for analysis of counting data previously recorded by a counter. Two companion documents will follow offering (1) analogous programe on-linus r conjunction fo i se n wit suitabla h y designed counter, and (2) programs for analysis of specimens introduced int successioa o f assano y batches from "quality-control pools" of the substance being measured. Suggestions for improvements of these programs and their documentation should be brought to the attention of: Robert A. -

TEC 201 Microcomputers – Applications and Techniques (3) Two Hours Lecture and Two Hours Lab Per Week

TEC 201 Microcomputers – Applications and Techniques (3) Two hours lecture and two hours lab per week. An introduction to microcomputer hardware and applications of the microcomputer in industry. Hands-on experience with computer system hardware and software. TEC 209 Introduction to Industrial Technology (3) This course examines fundamental topics in Industrial Technology. Topics include: role and scope of Industrial Technology, career paths, problem solving in Technology, numbering systems, scientific calculators, dimensioning and tolerancing and computer applications in Industrial Technology. TEC 210 Machining/Manufacturing Processes (3) An introduction to machining concepts and basic processes. Practical experiences with hand tools, jigs, drills, grinders, mills and lathes is emphasized. TEC 211 AC/DC Circuits (3) Prerequisite: MS 112. Two hours lecture and two hours lab. Scientific and engineering notation; voltage, current, resistance and power, inductors, capacitors, network theorems, phaser analysis of AC circuits. TEC 225 Electronic Devices I (4) Prerequisites: MS 112 and TEC 211. Three hours lecture and two hours lab. First course in solid state devices. Course topics include: solid state fundamentals, diodes, BJTs, amplifiers and FETs. TEC 250 Computer-Aided Design I (3) Prerequisites: MS 112, TEC 201 or equivalent. Two hours lecture and two hours lab. Interpreting engineering drawings and the creation of computer graphics as applied to two-dimensional drafting and design. TEC 252 Programmable Controllers (3) Prerequisite: TEC 201 or equivalent. Two hours lecture and two hours lab. Study of basic industrial control concepts using modern PLC systems. TEC 302 Advanced Technical Mathematics (4) Prerequisite: MS 112 or higher. Selected topics from trigonometry, analytic geometry, differential and integral calculus. -

Carbon Calculator *CE = Carbon Emissions

Carbon Calculator *CE = Carbon Emissions What is a “Carbon Emission”? A Carbon Emission is the unit of measurement that measures carbon dioxide (CO 2 ). What is the “Carbon Footprint”? A carbon footprint is the measure of the environmental impact of a particular individual or organization's lifestyle or operation, measured in units of carbon dioxide (carbon emissions). Recycling Upcycling 1 Cellphone = 20 lbs of CE 1 Cellphone = 38.4 lbs of CE 1 Laptop = 41 lbs of CE 1 Laptop = 78.7 lbs of CE 1 Tablet = 25 lbs of CE 1 Tablet = 48 lbs of CE 1 iPod = 10 lbs of CE 1 iPod = 19.2 lbs of CE 1 Apple TV/Mini = 20 lbs of CE 1 Apple TV/Mini = 38.4 lbs of CE *1 Video Game Console = 15 lbs of CE 1 Video Game Console = 28.8 lbs of CE *1 Digital Camera = 10 lbs of CE 1 Digital Camera = 19.2 lbs of CE *1 DSLR Camera = 20 lbs of CE 1 DSLR Camera = 38.4 lbs of CE *1 Video Game = 5 lbs of CE 1 Video Game = 9.6 lbs of CE *1 GPS = 5 lbs of CE 1 GPS = 9.6 lbs of CE *Accepted in working condition only If items DO NOT qualify for Upcycling, they will be properly Recycled. Full reporting per school will be submitted with carbon emission totals. Causes International, Inc. • 75 Second Avenue Suite 605 • Needham Heights, MA 02494 (781) 444-8800 • www.causesinternational.com • [email protected] Earth Day Upcycle Product List In working condition only. -

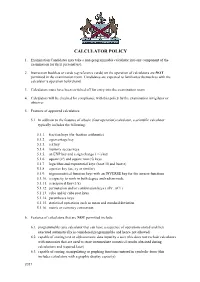

Calculator Policy

CALCULATOR POLICY 1. Examination Candidates may take a non-programmable calculator into any component of the examination for their personal use. 2. Instruction booklets or cards (eg reference cards) on the operation of calculators are NOT permitted in the examination room. Candidates are expected to familiarise themselves with the calculator’s operation beforehand. 3. Calculators must have been switched off for entry into the examination room. 4. Calculators will be checked for compliance with this policy by the examination invigilator or observer. 5. Features of approved calculators: 5.1. In addition to the features of a basic (four operation) calculator, a scientific calculator typically includes the following: 5.1.1. fraction keys (for fraction arithmetic) 5.1.2. a percentage key 5.1.3. a π key 5.1.4. memory access keys 5.1.5. an EXP key and a sign change (+/-) key 5.1.6. square (x²) and square root (√) keys 5.1.7. logarithm and exponential keys (base 10 and base e) 5.1.8. a power key (ax, xy or similar) 5.1.9. trigonometrical function keys with an INVERSE key for the inverse functions 5.1.10. a capacity to work in both degree and radian mode 5.1.11. a reciprocal key (1/x) 5.1.12. permutation and/or combination keys ( nPr , nCr ) 5.1.13. cube and/or cube root keys 5.1.14. parentheses keys 5.1.15. statistical operations such as mean and standard deviation 5.1.16. metric or currency conversion 6. Features of calculators that are NOT permitted include: 6.1. -

Mysugr Bolus Calculator User Manual

mySugr Bolus Calculator User Manual Version: 3.0.8_Android - 2021-06-02 1 Indications for use 1.1 Intended use The mySugr Bolus Calculator, as a function of the mySugr Logbook app, is intended for the management of insulin dependent diabetes by calculating a bolus insulin dose or carbohydrate intake based on therapy data of the patient. Before its use, the intended user performs a setup using patient-specific target blood glucose, carbohydrate to insulin ratio, insulin correction factor and insulin acting time parameters provided by the responsible healthcare professional. For the calculation, in addition to the setup parameters, the algorithm uses current blood glucose values, planned carbohydrate intake and the active insulin which is calculated based on the insulin action curves of the respective insulin type. 1.2 Who is the mySugr Bolus Calculator for? The mySugr Bolus Calculator is designed for users: diagnosed with insulin dependent diabetes aged 18 years and above treated with short-acting human insulin or rapid-acting analog insulin undergoing intensified insulin therapy in the form of Multiple Daily Injections (MDI) or Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion (CSII) under guidance of a doctor or other healthcare professional who are physically and mentally able to independently manage their diabetes therapy able to proficiently use a smartphone 1.3 Environment for use As a mobile application, the mySugr Bolus Calculator can be used in any environment where the user would typically and safely use a smartphone. 2 Contraindications 2.1 Circumstances for bolus calculation The mySugr Bolus Calculator can not be used when: the user's blood glucose is below 20 mg/dL or 1.2 mmol/L the user's blood glucose is above 500 mg/dL or 27.7 mmol/L the time of the log entry containing input data for the calculation is older than 15 minutes 1 2.2 Insulin restrictions The mySugr Bolus Calculator may only be used with the insulins listed in the app settings and must especially not be used with either combination or long acting insulin. -

100-0433.Pdf

Public Act 100-0433 SB1417 Enrolled LRB100 09551 MJP 19717 b AN ACT concerning safety. Be it enacted by the People of the State of Illinois, represented in the General Assembly: ARTICLE 1. CONSUMER ELECTRONICS RECYCLING ACT Section 1-1. Short title. This Act may be cited as the Consumer Electronics Recycling Act. References in this Article to "this Act" mean this Article. Section 1-5. Definitions. As used in this Act: "Agency" means the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency. "Best practices" means standards for collecting and preparing items for shipment and recycling. "Best practices" may include standards for packaging for transport, load size, acceptable load contamination levels, non-CED items included in a load, and other standards as determined under Section 1-85 of this Act. "Best practices" shall consider the desired intent to preserve existing collection programs and relationships when possible. "Collector" means a person who collects residential CEDs at any program collection site or one-day collection event and prepares them for transport. "Computer", often referred to as a "personal computer" or Public Act 100-0433 SB1417 Enrolled LRB100 09551 MJP 19717 b "PC", means a desktop or notebook computer as further defined below and used only in a residence, but does not mean an automated typewriter, electronic printer, mobile telephone, portable hand-held calculator, portable digital assistant (PDA), MP3 player, or other similar device. "Computer" does not include computer peripherals, commonly known as cables, mouse, or keyboard. "Computer" is further defined as either: (1) "Desktop computer", which means an electronic, magnetic, optical, electrochemical, or other high-speed data processing device performing logical, arithmetic, or storage functions for general purpose needs that are met through interaction with a number of software programs contained therein, and that is not designed to exclusively perform a specific type of logical, arithmetic, or storage function or other limited or specialized application. -

ISASP Calculator Policy

ISASP Bulletin – Calculator Policy General Information In accordance with the information given in the ISASP Accessibility and Accommodations Manual, the information below is provided as additional guidance around calculator use on the Iowa Statewide Assessment of Student Progress (ISASP). Subjects and Grades Calculators are permitted on all ISASP Mathematics (Grades 3-11) and Science (Grades 5, 8, and 10) assessments. Online Calculators For students taking the online ISASP Mathematics and Science assessments, a calculator is provided as a tool within the TestNav 8 testing engine. Students may access this tool for all items. Grades 3-5 will have access to a Desmos four-function calculator; Grade 6 will have access to a Desmos four-function calculator with percentage key; Grades 7-11 will have access to a Desmos scientific calculator. Prior to testing, students may become familiar with these calculators by accessing them either through the ISASP TestNav 8: Working With Online Tools tutorial or while taking the ISASP Mathematics or Science Practice Tests. Locally Approved Calculators Students taking either the paper or online ISASP are permitted to use locally approved (i.e., district approved) calculators. This includes the calculators that students use during regular instruction EXCEPT the following: • No smartphone/smart watch/tablet/computer apps, devices where notes or programs can be typed or stored, devices where pictures can be stored, devices with cameras, or devices with internet access. These devices are prohibited while taking all ISASP assessments. • No calculators with Computer Algebra System (CAS) capabilities. • No calculators with QWERTY format letter keys. • Examples of prohibited calculator models include the following. -

Scientific Calculator Operation Guide

SSCIENTIFICCIENTIFIC CCALCULATORALCULATOR OOPERATIONPERATION GGUIDEUIDE < EL-W535TG/W516T > CONTENTS CIENTIFIC SSCIENTIFIC HOW TO OPERATE Read Before Using Arc trigonometric functions 38 Key layout 4 Hyperbolic functions 39-42 Reset switch/Display pattern 5 CALCULATORALCULATOR Coordinate conversion 43 C Display format and decimal setting function 5-6 Binary, pental, octal, decimal, and Exponent display 6 hexadecimal operations (N-base) 44 Angular unit 7 Differentiation calculation d/dx x 45-46 PERATION UIDE dx x OPERATION GUIDE Integration calculation 47-49 O G Functions and Key Operations ON/OFF, entry correction keys 8 Simultaneous calculation 50-52 Data entry keys 9 Polynomial equation 53-56 < EL-W535TG/W516T > Random key 10 Complex calculation i 57-58 DATA INS-D STAT Modify key 11 Statistics functions 59 Basic arithmetic keys, parentheses 12 Data input for 1-variable statistics 59 Percent 13 “ANS” keys for 1-variable statistics 60-61 Inverse, square, cube, xth power of y, Data correction 62 square root, cube root, xth root 14 Data input for 2-variable statistics 63 Power and radical root 15-17 “ANS” keys for 2-variable statistics 64-66 1 0 to the power of x, common logarithm, Matrix calculation 67-68 logarithm of x to base a 18 Exponential, logarithmic 19-21 e to the power of x, natural logarithm 22 Factorials 23 Permutations, combinations 24-26 Time calculation 27 Fractional calculations 28 Memory calculations ~ 29 Last answer memory 30 User-defined functions ~ 31 Absolute value 32 Trigonometric functions 33-37 2 CONTENTS HOW TO -

High Performance Computing (HPC)

Vol. 20 | No. 2 | 2013 Globe at a Glance | Pointers | Spinouts Editor’s column Managing Editor “End of the road for Roadrunner” Los Alamos important. According to the developers of the National Laboratory, March 29, 2013.a Graph500 benchmarks, these data-intensive applications are “ill-suited for platforms designed for Five years after becoming the fastest 3D physics simulations,” the very purpose for which supercomputer in the world, Roadrunner was Roadrunner was designed. New supercomputer decommissioned by the Los Alamos National Lab architectures and software systems must be on March 31, 2013. It was the rst supercomputer designed to support such applications. to reach the petaop barrier—one million billion calculations per second. In addition, Roadrunner’s These questions of power eciency and unique design combined two dierent kinds changing computational models are at the core of processors, making it the rst “hybrid” of moving supercomputers toward exascale supercomputer. And it still held the number 22 spot computing, which industry experts estimate will on the TOP500 list when it was turned o. occur sometime between 2020 and 2030. They are also the questions that are addressed in this issue of Essentially, Roadrunner became too power The Next Wave (TNW). inecient for Los Alamos to keep running. As of November 2012, Roadrunner required 2,345 Look for articles on emerging technologies in kilowatts to hit 1.042 petaops or 444 megaops supercomputing centers and the development per watt. In contrast, Oak Ridge National of new supercomputer architectures, as well as a Laboratory’s Titan, which was number one on the brief introduction to quantum computing. -

Simple Hand-Held Calculating Unit to Aid the Visually Impaired with Voice Output

International Journal of Embedded systems and Applications(IJESA) Vol.5, No.3, September 2015 SIMPLE HAND-HELD CALCULATING UNIT TO AID THE VISUALLY IMPAIRED WITH VOICE OUTPUT ShreedeepGangopadhyay1,Molay Kumar Mondal1 and Arpita Pramanick1 1Department of Electronics & Communication Engineering, Techno India, Salt Lake, Kolkata ABSTRACT A thorough understanding in mathematics enhances educational and occupational opportunities for all, whether sighted or visually impaired.. However, solving complicated mathematical problems is difficult for visually challenged students in schools and universities as the calculators available in the markets with smooth input keys and LCD outputs are useless for them. Using the assistive technology which is basically a service or product to help people with disabilities function more independently has removed barriers to educate and employ people. An optimal solution for them is Braille calculator with audio output. In this paper, we have proposed a cost effective, hand-held, battery-driven, low power assistive device aiming the visually impaired people from low income settings. The input is given through a 4 by 4 Membrane keypad which has been Braille-embossed using indigenous methods. The output is announced in natural English by the audio unit via speakers and/or headphones up to two places of decimal point. The system is implemented on custom made open source Arduino platform, making it efficient and cost-effective. KEYWORDS Braille Keypad, calculator, Arduino, assistive technology, visually challenged. 1. INTRODUCTION “For most of us, technology makes things easier; however for a person with disabilities, it makes things possible”. Mathematics cultivates thinking and reasoning skills. It lays the foundation for systematic thinking through the numerical and spatial aspects of the objects. -

Azm2 Calculator Guidance

Calculator Guidance The AzM2 calculator guidelines are designed to provide appropriate support for students while still measuring a student’s mastery of the standards. On tests where calculators are permitted, it is ideal for a student to use the recommended acceptable calculator. If the recommended calculator is not available, students may use a calculator with less functionality. The Desmos Scientific and Graphing calculators have been customized for AzM2 and are embedded in online tests that allow the use of a calculator. These guidelines are for the assessment only. They are not intended to limit instruction in the classroom. Technology is a part of the Arizona Mathematics Standards, and students should still be interacting with technology as appropriate for engaging with and learning the standards. Grades 3-6: No calculators permitted on AzM2. Grades 7-8: Scientific calculator permitted on AzM2 Math Part 1 only. No calculators permitted on AzM2 Math Part 2. Scientific calculator should include these functions: standard four functions (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division), decimal, change sign (+/-), parentheses, square root, and π. They may NOT include: any problem solving or programming capabilities, place values, and inequalities. Sample acceptable calculator: TI-30X IIS or similar. Grade Graphing calculators permitted on AzM2 Math Part 1 and Part 2. 10: No calculators with Computer Algebra System (CAS) features are allowed. Calculators may NOT be capable of communication with other calculators through infrared sensors. NO instruction or formula cards, or other information regarding the operation of calculators such as operating manuals are permitted. The memory of any calculator with programming capability must be cleared, reset, or disabled when students enter and exit the testing room.