Weaving from the Margin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Difference Can One Year Make in the Health of a Community?

What difference can one year make in the health of a community? 2017 Report to the Community 15 Years of Making a Difference A TIMELINE: 2002-2017 How about fifteen years? This year Washington Regional Medical Center marks the 15th anniversary of its move to North Hills Boulevard, continuing a tradition of quality, compassionate care that began in 1950 on N. College Avenue. The new hospital building officially Women and Infants Center Emergency Department earns Mobile Dental Clinic opened on Tuesday, Aug. 27, 2002, at Level 2 Trauma Center designation is launched to provide opens, offering more 7 a.m., with patient transport beginning Willard Walker Hospice Home, from Arkansas Department of dental care and preventive at 8 a.m. When the move was safely than 130,000 square feet Fayetteville’s first inpatient hospice facility, Health, demonstrating that it education to community completed a few hours later, without is built near the medical center to serve offers the region’s highest level members who otherwise to serve the growing needs complications, it reflected many months patients of Washington Regional Hospice. of emergency care. could not access it. of meticulous planning and attention of area families. to detail by Washington Regional team 2008 2009 2010 2011 members,2012 who were enthusiastic2013 about 2014 2015 2016 2017 the future at North Hills. Ronald McDonald House — A medical office complex Total Joint Center Expansion project Just two years later, Washington Stroke Care Program the region’s first — opens consisting of a four-story is established at Regional welcomed William L. Bradley on top floor of the Women building and separate one- adds a fifth floor to the Washington Regional, is established at as its new chief executive and Infants Center. -

Altruism, Activism, and the Moral Imperative in Craft

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2009 Altruism, Activism, and the Moral Imperative in Craft Gabriel Craig Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Fine Arts Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1713 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Gabriel Craig 2009 All Rights Reserved Altruism, Activism, and the Moral Imperative in Craft A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University by Gabriel Craig Bachelor of Fine Arts (emphasis in Metals/ Jewelry), Western Michigan University, 2006 Director: Susie Ganch Assistant Professor, Department of Craft/ Material Studies Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2009 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge several people who have contributed to my success and development as an artist, writer, and as a person of good character in general. First, I would like to thank my father, without whose support the journey would have been much more difficult, Amy Weiks whose unwavering love and support has provided the foundation that allows me to take on so many projects, Susie Ganch, whose mentorship, honesty, and trust have helped me to grow like a weed over the past two years, Natalya Pinchuk whose high standards have helped me to challenge myself more than I thought possible, Sonya Clark who baptized me into the waters of craft and taught me to swim, and Dr. -

Spring Filings of Silver on a Silver Base Plate

Surface Texture Workshop Student Gallery February 22, Sat 10am-4pm $200 Tuition **Students provide their own materials. Fused Silver Texture is a surface texture of raised speckles of silver that can vary in size. It is created by fusing shavings or Spring filings of silver on a silver base plate. Reticulation is a surface texture resembling Amalgam Arts Atl is your community topography. It is achieved by establishing a metalsmithing and jewelry studio. fine silver coating around a sheet of sterling We offer a full range of workshops and silver. With concentrated heating, the classes to satisfy the needs of both the surface of the metal buckles leaving a beginning jeweler and intermediate and beautiful uneven surface. advanced jeweler Keum-boo is a traditional Korean metal technique where gold foil can be fused to a fine silver surface. The gold can be applied in a graphic pattern or a more painterly approach. Amalgam Arts Atlanta is 743 E. College Ave; Ste E, Decatur, GA 30030 and is easily reached by public transportation with the Avondale MARTA Station right next door! Check out Amalgam Arts Atlanta Facebook and Instagram pages daily to see more jewelry Ring by Wendy Tonsits making in action photos! To Register: Call to register! 404-447-2070 amalgamartsatlanta.com 404-447-2070 A unique approach to your artistic Silver Fabrication-Wendy Tonsits 4 Week Beginner Jewelry Making Class development In this “open format” style 8 session series, students For students who enjoy a project plan based class, are encouraged to explore their unique artistic our 4 Week Jewelry Making Class offers 2 projects expression while developing their skills in the basic where students will learn classic metal techniques. -

Guides for the Jewelry, Precious Metals, and Pewter Industries

38834 Federal Register / Vol. 70, No. 128 / Wednesday, July 6, 2005 / Proposed Rules meet the regulatory assembly articles that entered the customs § 303.20 Duty refund. requirements; or wages paid for the territory of the United States duty paid, * * * * * assembly and manufacture of jewelry with certain exceptions, up to the (a) * * * that contain HTSUS column 2 specified value of the certificate. (2) Eighteen month exemption. Any components. Certificates may be used to obtain duty article of jewelry provided for in HTSUS (D) Wages paid to those persons not refunds only when presented with a heading 7113, assembled in the insular engaged in the day-to-day assembly properly executed Form ITA–361P. possessions by a new entrant jewelry operations on the premises of the (3) ITA–361P ‘‘Request for Refund of manufacturer shall be treated as a company office, wages paid to any Duties on Articles that Entered the product of the insular possessions if outside consultants, wages paid to Customs Territory of the United States such article is entered into the customs outside the office personnel, including Duty Paid.’’ * * * territory of the United States no later but not limited to, lawyers, gardeners, * * * * * than 18 months after such producer construction workers and accountants; 8.–9. Section 303.17 is amended by commences jewelry manufacturing or wages paid to employees not working revising paragraph (b)(6); by jewelry assembly operations in the on the premises of the company office redesignating paragraphs (b)(7) and insular possessions. and wages paid to employees who do (b)(8) as paragraphs (b)(8) and (b)(9); * * * * * not qualify as permanent residents in and by adding a new paragraph (b)(7) to 11. -

Spring 2020 Class Catalog

Spring 2020 Class Catalog Photo Credit: Above It All by Michelle Firment Reid Mark Your Calendars…………………..….pg 2 Special Events………………………... pg 7 Glass…………………………………pg 12 Facility Rentals,……………………….…...pg 3 Featured Workshop…………………...pg 8 Drawing, Painting, & Printmaking…pg 13 Our Instructors……………………….….pg 4-5 Clay……………………………………..pg 9 Fiber Arts & Textiles………………..pg 15 Private Groups……………………….…….pg 6 Jewelry & Metals……………………..pg 10 Course Calendar……………….pg18 - 19 Mark Your Calendars for Spring 2020! Oh, the joys of Spring! We’re excited to bring a new teaching artist into the fold at WaterWorks Art Center as we welcome Jini Kim. Jini will teach “Beginner’s Drawing,” an often-asked-for introductory drawing series of classes beginning on Thursday, April 2, 1 - 4 p.m. WaterWorks Spring Break Art Camp is scheduled for March 16 - 20, 9 a.m. - 4 p.m. for young artists ages 7 - 11. Enrollment begins February 1 and is limited to 10 participants. Questions? Give us a call at (918) 596-2440. Tuition is $125 and includes all art supplies and a week of fun. Multidisciplinary artist, Michelle Firment Reid, brings her inspired vision to guide participants through the process of exploring a wordless open-form of writing and art in her two-day feature workshop, “Asemic Writing: Freedom & Fluidity” on Friday and Saturday, April 3 and 4. Space is limited on a first-come, first-served basis for this WaterWorks Advisory Council sponsored event. Enroll online for the workshop at www.waterworksartcenter.com. Executive Director WaterWorks Hours of Operation: Lee Anne Zeigler, [email protected] Mondays - Thursdays 8:30 a.m. -

The Mechanics of Jewelry

THE MECHANICS OF JEWELRY SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS BY JOSHUA D. SANCHEZ ADVISOR: PATRICIA NELSON BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page i Table of Contents ii Chapter One: Statement of Problem 1 Chapter Two: Influences 2 - 9 Chapter Three: Description of Artworks and Process 10 - 24 Chapter Four: Conclusion 25 - 28 Chapter Five: Exhibition Statement 29 Appendix 30 - 37 Works-Cited 38 - ii - Statement of Problem There are three major questions and obstacles that I will deal with in the creation of my art. The first question, “how do I incorporate industrialized objects such as screws and gears into jewelry?” comes from my love of mechanical objects that are parts of a larger whole. With my second question, “how can I make these industrialized objects out of precious metals, primarily silver?” I attempt to meld industrial parts with precious materials. The third question is, “how can I incorporate gemstones into these objects?” Many of the gemstones that I will be using in my work are rather large in comparison to mainstream jewelry. The successful integration of these large gemstones will be critical to the design and aesthetic appearance of some of my work; the success of the rest of my work will be contingent on the integrated mechanics, specifically gears. - 1 - Influences My initial influence was that of the Steampunk Genre, which was influenced by the mechanics of the Industrial Revolution. Steampunk is a genre of literature and art set in the Victorian era where steam is the predominant power supply. -

Summer Brochure 2016

SUMMER BROCHURE 2016 What’s New? Auracle® AGT Blue™ � � � � � � � � � � � � 2 NEW! Elma “EASY” Ultrasonics BestBuilt Engravers � � � � � � � � � � � 10 Superior Cleaning Power and Easy to Use! Diamond Embedded Polisher � � � � 8 The Elma EASY series includes 9 quality units of different sizes Digital V Electroplater � � � � � � � � � � 4 and is characterized by simple, user-friendly operation. With Double Flex Shaft Hanger � � � � � � � 5 100% ultrasonic power at a frequency of 37 kHz, the Pulse Durston Disc Cutters � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 function and visual warning (bath temperature reaches the set Easy 30H, 3 qt. Durston Euro Dust Collectors � � � � 11 limit), the Elmasonic EASY solves typical cleaning tasks in the Features: Elma “Easy” Ultrasonics � � � � � � � � �1 processing of jewelry and industrial parts quickly and efficiently. • More power with Pulse function for removing dirt, polishing compound and hand cream. Elmasteam Basic Steamer � � � � � � � �1 The “Pulse” function can be activated to remove tenacious, mineral soiling and polishing pastes, increasing the ultrasonic • Visual limit temperature warning to protect sensitive parts. Foredom Dust Collector � � � � � � � � � 3 power by up to 20%, so that any soiling will be removed easily • Easy handling with safety shutdown for more user safety. Foredom Work Chamber � � � � � � � � 3 and quickly. The limit temperature can be adjusted according • Pulse Function for 20% faster cleaning, removes caked on drift formLabs 3D Printer � � � � � � � � � � � � 9 to individual requirements. When the set temperature limit is compounds. Galloni G1 + G3 Ultimate � � � � � � � � � 9 reached the unit gives out a visual warning that helps to protect • Electronic timer up to 30 minutes and also able to work continuously. • Thermostatically controlled heating with safety shut off function. GemOro DSPRO 1067 � � � � � � � � � � � � 6 sensitive items from damage due to high temperatures. -

JEWELRY TRADES at Macomb Community College

JEWELRY TRADES at Macomb Community College JEWELRY TRADES CERTIFICATE The Jewelry Trades Program consists of eight core classes, and is designed to enhance the knowledge of those employed in the jewelry industry, as well as those with an interest in gemstones, jewelry and jewelry repair. Upon successful completion of all classes, you’ll earn a Macomb Workforce & Continuing Education Certificate of Completion in Jewelry Trades. Jewelry Repair-Bench Skills I Focus on tools, safety issues, and basic jewelry metalsmithing and stone-setting practices. $20 material fee payable to instructor at first session. Jewelry Repair-Bench Skills II Gain knowledge of chain repair, riveting, head and prong replacement, prong tipping, and post soldering. $20 material fee payable to instructor at first session. Gemstone Identification This hands-on mini workshop is designed to reveal the history and nature of gemstones: where they are found, how they are cut, what colors to expect, and what to look for when purchasing a stone. Buying and Selling Precious Metals Gain hands-on experience identifying, evaluating, testing, and appraising precious metals. Gemology–Colored Stones Cultivate your gemology identification skills. See, touch, and evaluate a wide range of organic, precious, and semi-precious colored gemstones in the rough and cut. Obtain skills to recognize numerous stones, name each gemstone properly, and try to determine where the stones were mined. Lapidary and Cabochon Learn how to cut and polish gemstones for jewelry making. Equipment and safety issues will be introduced. Wear old clothes, safety goggles, and a dust mask. $20 stone fee payable to instructor at first session. -

Preparing for Platinum Bench Work

Preparing for Platinum Bench Work Sooner or later, most bench jewelers will have to work with platinum. It’s only natural: As demand for the white metal has increased over the past several years, the amount of platinum jewelry that needs to be repaired or fabricated has also risen. Platinum bridal pieces, cocktail rings, bracelets, and chains - all these and more will at some point cross the jeweler’s bench. This also gives rise to one of today’s most frequently asked questions: How difficult is platinum to work with? The answer: Not very - unless you don’t have the necessary information. To illustrate, let’s say a bench jeweler must fabricate a four-prong solitaire ring. It’s the same kind of ring he’s made many times in his career, except this time it will be made from platinum. He’s never worked with this white metal before, but he’s not worried. After all, he’s had plenty of experience with gold; how different can it be? Confidently, he rolls the platinum stock to the proper size, creating the wire that will form the gallery for the prong assembly. Placing it on a charcoal- soldering block, he begins to anneal the wire in preparation for soldering. He focuses the flame of his trusty oxygen/acetylene torch and watches as the platinum turns a bright orange. His uncovered eyes squint as he looks into the blinding light, and he has trouble focusing. He’s about to take out a pair of sunglasses from his pocket when he notices that his charcoal block is starting to decay rapidly. -

Sloane Street

A TUFTS COMMUNICATIONS FINE JEWELRY PUBLICATION BC CLARK MAGAZINE • OKLAHOMA CITY, OK 2016/2017 ISSUE 7 MAGAZINE The Incomparable Roberto Coin The Rolex Standard A Man’s World of Jewelry The Essential Seven A Mother-and-Daughter Dream Team SLOANE STREET 2016/2017 • ISSUE 7 B:18.25” T:18” S:17.25” B:11.125” S:10.125” T:10.875” 49785DY_16_BC CLARK MAG_SPD_WS_DEC_V1.indd 1 FS:8.25” FS:8.25” 9/29/16 5:16 PM F:9” F:9” Publication: BC CLARK MAGAZINE Bleed: 18.25” x 11.125” Creative Director: STEPHAN ELLWOOD Notes: None Publication Date: DEC Trim: 18” x 10.875” Art Director: MATT KRAUS File Name: DY16_BC CLARK MAG_2P_SPRD_WS_ DEC_V1.indd Live: 17.25” x 10.125” Production Director: STEPHEN ELLWOOD Date: 9-29-2016 4:15 PM Position: IFC Production Coordinator: CAITLIN PHELPS Media Buying: CARLY POPOFSKY Fonts: None Images: Shot7_Hol16_c21118-36-8_V5_pub_ Studio Artist: IRENE DARKEN_V3.tif (CMYK; 714 ppi; 42%), Shot1_ Hol16_c21118-25-8_V5_pub.tif (CMYK; 958 ppi; 31.31%), DAVID YURMAN_LOGO_BLACK 75.eps (121.99%) APPROVAL CREATIVE DIRECTOR / ART DIRECTOR PRODUCTION DIRECTOR MEDIA BUYING STUDIO ARTIST PRODUCTION COORDINATOR COPYWRITER B:18.25” T:18” S:17.25” B:11.125” S:10.125” T:10.875” 49785DY_16_BC CLARK MAG_SPD_WS_DEC_V1.indd 1 FS:8.25” FS:8.25” 9/29/16 5:16 PM F:9” F:9” Publication: BC CLARK MAGAZINE Bleed: 18.25” x 11.125” Creative Director: STEPHAN ELLWOOD Notes: None Publication Date: DEC Trim: 18” x 10.875” Art Director: MATT KRAUS File Name: DY16_BC CLARK MAG_2P_SPRD_WS_ DEC_V1.indd Live: 17.25” x 10.125” Production Director: STEPHEN ELLWOOD Date: 9-29-2016 4:15 PM Position: IFC Production Coordinator: CAITLIN PHELPS Media Buying: CARLY POPOFSKY Fonts: None Images: Shot7_Hol16_c21118-36-8_V5_pub_ Studio Artist: IRENE DARKEN_V3.tif (CMYK; 714 ppi; 42%), Shot1_ Hol16_c21118-25-8_V5_pub.tif (CMYK; 958 ppi; 31.31%), DAVID YURMAN_LOGO_BLACK 75.eps (121.99%) APPROVAL CREATIVE DIRECTOR / ART DIRECTOR PRODUCTION DIRECTOR MEDIA BUYING STUDIO ARTIST PRODUCTION COORDINATOR COPYWRITER The Originator of Cultured Pearls. -

The Technology in Laser Welding

The Technology In Laser Welding What is laser welding? Simply stated, laser welding is the ability to weld metals, using amplified light as the source, to produce a solid weld. It sounds complicated, but is really quite simple. Laser welding actually uses a specific wavelength of light to accomplish the welding process. This light is concentrated, adjusted, and controlled by jeweler operators, in much the same way as they would control and adjust the flame of a soldering torch. However, compared to soldering, laser welding is faster, cleaner, and more cost-effective for many manufacturing and repair applications. What metals can be welded with the laser? All of the traditional jewelry metals can be laser welded—all base metals, karat gold, sterling silver, titanium, palladium and platinum. Platinum, historically one of the most difficult metals to work with and repair, is one of the easiest metals on which to perform laser weld repairs! Welding different metal groups is also possible, i.e. gold to platinum, sterling to gold, etc. How difficult is it to operate a laser welding machine? Our laser welders are extremely user-friendly. There is a short learning curve, so that any entry-level jewelry personnel can be quickly and easily trained to perform basic welding applications. While there is no substitute for an experienced bench jeweler, many repairs, which could have only been handled by a jeweler, can now be taken care of by utilizing more of your shop staff. Experienced jewelers, who have these laser welders, generally find that it takes between 10–20 hours of hands-on practice using the laser welder to become proficient for all their standard applications. -

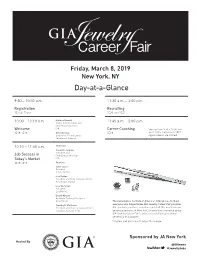

2019 Career Fair Program

Friday, March 8, 2019 New York, NY Day-at-a-Glance 9:30 – 10:00 a.m. 11:30 a.m. – 2:00 p.m. Registration Recruiting 1E Hall Foyer 1E20 and 1E21 10:00 – 10:10 a.m. Kathryn Kimmel 11:45 a.m. – 2:00 p.m. Senior Vice President and Chief Marketing Officer Welcome GIA Career Coaching Sign up from 9:30 – 10:00 a.m. 1E18-1E19 Amanda Gizzi 1E08 and 12:00 – 1:45 p.m. in 1E07 Director of PR and Events Appointments are limited! Jewelers of America 10:10 – 11:30 a.m. Moderator: Susan M. Jacques President and Job Success in Chief Executive Officer Today’s Market GIA 1E18-1E19 Panelists: Caryl Capeci President Hearts On Fire Lisa Bridge President and Chief Executive Officer Ben Bridge Jeweler Lisa Nikfarjam President Lisa Nik Inc. Daniel Wisner Assistant Technical Designer Alexis Bittar The Gemological Institute of America® (GIA) wishes to thank Timothy B. Matthews everyone who helped make GIA Jewelry Career Fair possible: President and Chief Executive Officer Our speakers, coaches, recruiters and staff. We also thank our Jewelry Television (JTV) generous sponsor, JA New York, for providing the venue space. GIA Jewelry Career Fair is only successful because of your generosity and support! Program and participants subject to change. Sponsored by JA New York Hosted By @GIAnews #JewelryJobs Recruiter Info: Job Opportunities: Recruiter Info: Job Opportunities: Ada Diamonds • Sales Manager Brilliant Earth • Staff Gemologist • Operations Manager • Customer Experience Jason Payne Kim Garcia • Operations Intern Assistant New York, NY San Francisco, CA • Customer Experience T 650 416 7576 T 415 226 7811 Manager E [email protected] E [email protected] • Operations Assistant adadiamonds.com brilliantearth.com • Operations Manager Ada Diamonds is a bespoke fine jeweler proudly working Founded in 2005, Brilliant Earth is the global leader in exclusively with lab diamonds.