Anglia Ruskin University Using Theological Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards a Truly Catholic and a Truly Asian Church: an Asian Wayfaring Theology of the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences (FABC) 1970-2012

Department of Systematic Theology University of Helsinki Helsinki Towards a Truly Catholic and a Truly Asian Church: An Asian Wayfaring Theology of the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences (FABC) 1970-2012 Jukka Helle Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Theology at the University of Helsinki in Auditorium XII, on the 23rd of May 2018 at 12 o’clock. FABC Ruby Jubilee Prayer (2012) God ever faithful, we praise you for your abiding presence in our pilgrimage in this land of Asia, hallowed by the life and mission of your Son Jesus Christ. We thank you for the mysterious presence of your Spirit in the depth and breadth of the spiritual quest of our people, in their enduring cultures and values, and in the struggles of the poor. We raise our hearts in gratitude for the gift of the Church in Asia, the little flock you tend with provident care in her mission of proclaiming your Gift, Jesus Christ the Giver of Life. Father, we thank you for the Federation of the Asian Bishops’ Conferences, an instrument of communion you have granted us for the past forty years. Your Spirit accompanied us in our common search for the paths of mission in our continent. As we celebrate your blessing, renew your Church in Asia with a fresh outpouring of your Spirit. Make us grow in greater unity; rekindle the fire of your Spirit to be credible bearers of the Good News of Jesus. Empower us as we “go” on the roads of Asia, that in inter-religious dialogue and cultural harmony, in commitment to the poor and the excluded, we may courageously tell the story of Jesus. -

Companion to the Encyclical of Pope Benedict Xvi on “God Is Love”

COMPANION TO THE ENCYCLICAL OF POPE BENEDICT XVI ON “GOD IS LOVE” Fr. Tissa Balasuriya ope Benedict XVI’s much anticipated first Encyclical has been welcomed as evidence of a more congenial personality, of a less severe figure than his P tenure as supervising Cardinal of the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith had suggested. The Encyclical consists of two parts: I) “the unity of love in creation and in salvation history” (nos 2–18) II) “Caritas the Practice of Love by the Church as a “Community of Love” (nos 19–42). It is articulate, well reasoned, reflective, erudite. Its language, personal in style, conveys a sensibility firmly rooted in the Western intellectual tradition: philosophy, Biblical studies, and the classics are amply and dexterously refer- enced. And its message is highly appealing: “God is love, and he who abides in love abides in God, and God abides in him.” The reception to the Encyclical has been largely positive (especially consid- ering that the Pope refrains from pontificating here on the divisive issues of sex- ual morality). He displays a personal understanding of the value and meaning of love in all its multifarious, interconnected complexity, as eros, philia and agape: of love as physical and sexual expression, of love as friendship, and as other-centered in care and service of the other. He links all these to God’s love for individuals and humanity, revealed and expressed in Christ. In a spirit of compromise and understanding, he has apparently endeavored to reconcile mutually opposed positions. Part I has been applauded by those concerned with issues of inter-personal morality. -

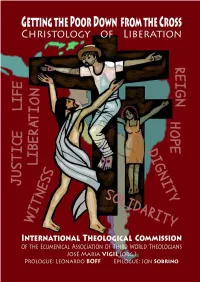

Getting the Poor Down from the Cross: a Christology of Liberation

GETTING THE POOR DOWN FROM THE CROSS Christology of Liberation International Theological Commission of the ECUMENICAL ASSOCIATION OF THIRD WORLD THEOLOGIANS EATWOT GETTING THE POOR DOWN FROM THE CROSS Christology of Liberation José María VIGIL (organizer) International Teological Commission of the Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians EATWOT / ASETT Second Digital Edition (Version 2.0) First English Digital Edition (version 1.0): May 15, 2007 Second Spanish Digital Edition (version 2.0): May 1, 2007 Frist Spanish Digital Edition (version 1.0): April 15, 2007 ISBN - 978-9962-00-232-1 José María VIGIL (organizer), International Theological Commission of the EATWOT, Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians, (ASETT, Asociación Ecuménica de Teólogos/as del Tercer Mundo). Prologue: Leonardo BOFF Epilogue: Jon SOBRINO Cover & poster: Maximino CEREZO BARREDO © This digital book is the property of the International Theological Commission of the Association of Third World Theologians (EATWOT/ ASETT) who place it at the disposition of the public without charge and give permission, even recommend, its sharing, printing and distribution without profit. This book can be printed, by «digital printing», as a professionally formatted and bound book. Software can be downloaded from: http://www.eatwot.org/TheologicalCommission or http://www.servicioskoinonia.org/LibrosDigitales A 45 x 65 cm poster, with the design of the cover of the book can also be downloaded there. Also in Spanish, Portuguese, German and Italian. A service of The International Theological Commission EATWOT, Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians (ASETT, Asociación Ecuménica de Teólogos/as del Tercer Mundo) CONTENTS Prologue, Getting the Poor Down From the Cross, Leonardo BOFF . -

Revisiting the Case of Tissa Balasuriya, OMI Ambrose Ih-Ren Mong, OP the Chinese University of Hong Kong

Dialogue under Fire: Revisiting the Case of Tissa Balasuriya, OMI Ambrose Ih-Ren Mong, OP The Chinese University of Hong Kong fter the publication of Tissa Balasuriya’s book adopt a more just and humane procedure in carrying out AMary and Human Liberation, the Congregation for its duties. The story of Balasuriya’s excommunication the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) accused Balasuriya of and reconciliation also brings home the importance of deviating from the integrity of the truth of the Catholic dialogue within the Church, the right of theologians to faith. For this offence, he was excommunicated in dissent, and the need for the Church to be open to theo- January 1997. The severity of the punishment meted logians operating from a non-Western paradigm. out to him by the CDF made Balasuriya a type of ce- Towards an Asian Theology lebrity among Third World theologians. Many were sympathetic towards him and dreaded what the CDF Born on 29 August 1924 in Kahatagasdigiliya, Sri might do next to those specializing in the areas of reli- Lanka, into a middle-class Catholic family, Sirimevan gious pluralism and interreligious dialogue. Mary and Tissa Balasuriya joined the Congregation of the Oblates Human Liberation is not so much about Mariology as of Mary Immaculate in 1945, made his religious profes- about Western theologies and the missionary enterprise. sion in 1946, and was ordained in Rome in 1952. After Even so, Balasuriya was accused of challenging funda- many years of working in various educational, social, mental Catholic beliefs, such as Original Sin and the economic, and religious projects, Balasuriya passed Immaculate Conception, as well as allegedly embracing away after a long illness on 17 January 2013 at the age religious pluralism and relativism. -

Copyright © Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC. All Rights Reserved

Copyright © Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC. All rights reserved. THE COMMUNITY OF BELIEVERS Copyright © Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC. All rights reserved. ................. 18662$ $$FM 01-22-15 09:46:18 PS PAGE i Previously Published Records of Building Bridges Seminars The Road Ahead: A Christian–Muslim Dialogue, Michael Ipgrave, editor (London: Church House, 2002) Scriptures in Dialogue: Christians and Muslims Studying the Bible and the Qura¯n Together, Michael Ipgrave, editor (London: Church House, 2004) Bearing the Word: Prophecy in Biblical and Qura¯nic Perspective, Michael Ipgrave, editor (London: Church House, 2005) Building a Better Bridge: Muslims, Christians, and the Common Good, Michael Ipgrave, editor (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2008) Justice and Rights: Christian and Muslim Perspectives, Michael Ipgrave, editor (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2009) Humanity: Texts and Contexts: Christian and Muslim Perspectives, Michael Ipgrave and David Marshall, editors (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2011) Communicating the Word: Revelation, Translation, and Interpretation in Christianity and Islam, David Marshall, editor (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2011) Science and Religion: Christian and Muslim Perspectives, David Marshall, editor (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2012) Tradition and Modernity: Christian and Muslim Perspectives, David Marshall, editor (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2012) Prayer: Christian and Muslim -

The Catholic Church and the Chicago Parliaments of Religions

Standing with Unfamiliar Company on Uncommon Ground: The Catholic Church and the Chicago Parliaments of Religions by Carlos Hugo Parra A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Theory and Policy Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Carlos Hugo Parra 2012 Standing with Unfamiliar Company on Uncommon Ground: The Catholic Church and the Chicago Parliaments of Religions Carlos Hugo Parra Doctor of Philosophy Theory and Policy Studies in Education University of Toronto 2012 Abstract This study explores the struggle of the Catholic Church to be true to itself and its mission in the midst of other religions, in the context of the non-Catholic American culture, and in relation to the modern world and its discontents. As milestones of the global interfaith movement, American religious freedom and pluralism, and the relation of religion to modernity, the Chicago Parliaments of Religions offer a unique window through which to view this Catholic struggle at work in the religious public square created by the Parliaments and the evolution of that struggle over the course of the century framed by the two Chicago events. In relation to other religions, the Catholic Church stretched itself from an exclusivist position of being the only true and good religion to an inclusivist position of recognizing that truth and good can be present in other religions. Uniquely, Catholic involvement in the centennial Parliament made the Church stretch itself even further, beyond the exclusivist-inclusivist spectrum into a pluralist framework in which the Church acted humbly as one religion among many. -

The Word-Crucified in the Theology of Aloysius Pieris, Sj

THE WORD-CRUCIFIED IN THE THEOLOGY OF ALOYSIUS PIERIS, S.J. PIERIS’ CONTRIBUTION TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF A CHRISTIAN THEOLOGY OF RELIGIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF SRI LANKA By W.F. Romesh Lowe, O.M.I. A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Theology, Saint Paul University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology and Doctor of Theology Ottawa, Canada 2012 © W. F. Romesh Lowe, O.M.I., Ottawa, Canada, 2012 Abstract This project is a study of Pieris’ theological writings with a focus on his particular contribution to the post-Vatican II development of the theology of religions and its implication for a renewed understanding of divine revelation/salvation and Christ in the context of religious pluralism and poverty in Sri Lanka. The main objective of this project is to bring to attention Pieris’ notion of the Word-Crucified, a central notion of his theology of religions, as a catalyst and a compass to set the right direction with a reverential attitude towards other religions in the Sri Lankan context. The reason for this undertaking is the reality of Christianity’s place as “stranger” and “intruder” (foreignness) in the context of Sri Lanka. Hence, the Sri Lankan Church is in need of a language to communicate the credibility of revelation in the process of becoming a Church of Sri Lanka with a sound theology that views other religions as co-partners within God’s one single but progressive and holistic economy of salvation for humanity. Here, we underscore that Buddhism, from the time of its introduction to Ceylon in the third century B.C. -

Samvada, 2012 Issue

A Sri Lankan Catholic Journal on Interreligious Dialogue Vol. 1 November 2012 Savāda: A Sri Lankan Catholic Journal on Interreligious Dialogue Executive Editor: Claude Perera, OMI, SSL (Rome), Ph.D. (Leuven), M.A. (Kelaniya) Editorial Board: John Cherian Kottayil, B.A. and M.A. (Kerala), M.Th. and Ph.D. (Leuven) Chrysantha Thillekeratne, OMI, B.Ph., B.Th. (Rome), M.A. (Chennai) Dolores Steinberg, B.A. (College of St. Teresa, Winona, Minnesota) Savāda: A Sri Lankan Catholic Journal on Interreligious Dialogue is owned and published by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, Colombo Province (Sri Lanka); Fr. Rohan Silva, OMI, Provincial; De Mazenod House, 40 Farm Rd., Colombo, CO 01500, Sri Lanka. Savāda is published at the Centre for Society and Religion, 281 Deans Rd., Colombo, CO 01000, Sri Lanka. Material published in Savāda does not necessarily reflect the views of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate or the editors. Copyright © 2012 by The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, Colombo Province, Sri Lanka. All rights reserved. All communications regarding articles, editorial policy and other matters should be sent to Claude J. Perera, OMI, Executive Editor; Suba Seth Gedara, Centre for Christian-Buddhist Dialogue, 12th Mile Post, Raja Mawatha, Alukalawita, Buttala, Sri Lanka. Tel.: +94 75 845 1152; +94 55 227 3634; Email: [email protected] Volume 1, November, 2012 Savāda: A Sri Lankan Catholic Journal on Interreligious Dialogue Vol. 1 November, 2012 This Maiden Issue of Savāda is a Festschrift dedicated to the fond memory of the late Fr. Michael Rodrigo, OMI, a pioneer in Buddhist-Christian Dialogue in Sri Lanka whose 25th anniversary of death falls on 10 November, 2012. -

On Religion and Cultural Policy: the Case of the Roman Catholic Church

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published version may require a subscription. Author(s): Oliver Bennett Article Title: On religion and cultural policy: notes on the Roman Catholic Church Year of publication: 2009 Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/10286630802609972 Publisher statement: None On Religion and Cultural Policy: Notes on the Roman Catholic Church Oliver Bennett Abstract This paper argues that religious institutions have largely been neglected within the study of cultural policy. This is attributed to the inherently secular tendency of most modern social sciences. Despite the predominance of the ‘secularisation paradigm’, the paper notes that religion continues to promote powerful attachments and denunciations. Arguments between the ‘new atheists’, in particular, Richard Dawkins, and their opponents are discussed, as is Habermas’s conciliatory encounter with Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI). The paper then moves to a consideration of the Roman Catholic Church as an agent of cultural policy, whose overriding aim is the promotion of ‘Christian consciousness’. Discussion focuses on the contested meanings of this, with reference to (1) the deliberations of Vatican II and (2) the exercise of theological and cultural authority by the Pope and the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF). -

Structures of Grace: Catholic Nongovernmental Organizations and the Mission of the Church

Structures of Grace: Catholic Nongovernmental Organizations and the Mission of the Church Author: Kevin Joachim Ahern Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104378 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2013 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of Theology STRUCTURES OF GRACE: CATHOLIC NONGOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS AND THE MISSION OF THE CHURCH A Dissertation by KEVIN J. AHERN submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2013 © copyright by KEVIN J. AHERN 2013 Structures of Grace: Catholic Nongovernmental Organizations and the Mission of the Church By Kevin J. Ahern Director: David Hollenbach, SJ Abstract Transnational Catholic nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are among the most active agents in the promotion of the global common good as they seek to overcome the structures of sin that divide the human family. This dissertation investigates the theological and ethical significance of Catholic NGOs by developing a critical framework that uncovers the relationship between these organizations and the church’s mission. Part One considers the global context and theoretical foundations of Catholic NGO action by examining social scientific literature (Chapter One) and modern Catholic teaching on the relationship between mission and justice (Chapter Two). Part Two places the theoretical foundations into dialogue with two case studies—the International Movement of Catholic Students-Pax Romana (Chapter Three) and the Jesuit Refugee Service (Chapter Four). This critical investigation of both theory and praxis illuminates several missiological, pneumatological, and ethical conclusions that are addressed in the final part (Chapter Five). -

Eucharist and Human Liberation

Eucharist and Human Liberation Tissa Balasuriya OMI Quest Series 50 Published by the Centre for Society and Religion 281, Deans Road, Colombo 10 Sri Lanka July 1977 1 FOREWORD It is with a certain sense of pride that I introduce this second book of Fr. Balasuriya to the general public. I have always bemoaned the fact that Asia, after so many years of Christianity has not produced any significant theological writing. This book can, without exaggeration, be said to contain the theological reflections of an Asian theologian. It is a faith reflection of a priest, on one of the most sacred and essential functions of the priest – the celebration of the Eucharist. The Asian Faith experience is a unique and a complex one different from the Latin American or the African experience though there may be some elements in common. The Author tries to make articulate this experience out of a sheer loyalty to the Universal Church. He tries to portray to us what the Eucharist should be in the light of Scripture and tradition. He therefore takes a long and close look at what it has been until now and argues that this most liberative act has been so domesticated by a Socio- Economic system that it now enslaves and domesticates its participants. He is also extremely sensitive to the longings and searchings of committed priests to make the Eucharist meaningful to themselves and to society. It is a happy coincidence that the Author has decided to publish these reflections on the 25th Anniversary of his Ordination to the priesthood, which falls on the 6th of July 1977. -

Bulletin 2009 September-October

SEDOS Vol. 41, No. 9/10 Bulletin 2009 September-October Editorial 226 Paul’s Dynamic Mission Principles - A Missioner Reflection - James H. Kroeger, M.M 227 Christian Mission as Reconciliation Indunil Janaka Kodithuwakk 233 A Missing Dimension in Papal Encyclical Tissa Balasuriya, OMI 239 From Evangelization to Reconciliation, Justice and Peace: Towards a Paradigm Shift in African Mission Priorities Munachi E. Ezeogu, C.S.Sp. 245 Au cœur de la pauvreté, devenir tous humains – Misère intolérable ou pauvres gênants ? – Pierre Diarra 252 Quand l’amour l’emporte ... Bomki Mathew 255 The Earth is God’s Temple: Ecological Spirituality P.M. Fernandop. 258 Sedos - Via dei Verbiti, 1 - 00154 Roma Servizio di Documentazione e Studi TEL.: (+39)065741350 / FAX: (+39)065755787 Documentation and Research Centre E-mail address: [email protected] Centre de Documentation et de Recherche Homepage: http://www.sedos.org Servicio de Documentación e Investigación 2009/226 EDITORIAL Saint Paul, apostle par excellence, tirelessly laboured to spread the Gospel, particularly to the Gentiles. His missionary travels and encounter with diverse peoples, cultures, and religions form the matrix or context of his missionary methods. A comprehensive examination of Paul’s writings yields much mission wisdom and insight shaped by his apostolic experience and dynamic faith. In “Paul’s Dynamic Mission Principles – A Missioner Reflection”, James H. Kroeger, M.M., suggests ten “mission principles” – derived from Pau’s profound reflection — “applicable” to missionary engagements today. Spreading the Gospel means to be living witnesses to the love of God that forgives and reconciles. Indunil Janaka Kodithuwakk, in “Christian Mission as Reconciliation”, analyses the roots of the conflict in Sri Lanka, while presenting forgiveness, reconciliation and peace as the path for all men and women of good will to meet this challenge.