[Speech at The] Economic Forums, Peoria, Illinois and Quad Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper Mississippi River Conservation Opportunity Area Wildlife Action Plan

Version 3 Summer 2012 UPPER MISSISSIPPI RIVER CONSERVATION OPPORTUNITY AREA WILDLIFE ACTION PLAN Daniel Moorehouse Mississippi River Pool 19 A cooperative, inter-agency partnership for the implementation of the Illinois Wildlife Action Plan in the Upper Mississippi River Conservation Opportunity Area Prepared by: Angella Moorehouse Illinois Nature Preserves Commission Elliot Brinkman Prairie Rivers Network We gratefully acknowledge the Grand Victoria Foundation's financial support for the preparation of this plan. Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................................. ii Acronym List .............................................................................................................................. iii I. Introduction to Conservation Opportunity Areas ....................................................................1 II. Upper Mississippi River COA ..................................................................................................3 COAs Embedded within Upper Mississippi River COA ..............................................................5 III. Plan Organization .................................................................................................................7 IV. Vision Statement ..................................................................................................................8 V. Climate Change .......................................................................................................................9 -

Project Description

Chicago to Quad Cities Passenger Rail Project Grade Crossing Design Illinois DOT - Various Locations Project Description The project provides Program Management along with planning and preliminary engineering services for the Illinois Department of Transportation to implement passenger rail service on the Chicago to Iowa City corridor within the State of Illinois project limits. The Chicago-Iowa City Passenger Rail Service Development Program of Iowa and Illinois will establish passenger rail service between Chicago, the Quad Cities, Illinois and Iowa City, Iowa, 219.5 miles. The service will be hosted by BNSF Railway (BNSF) and Iowa Interstate Railroad (IAIS), and be operated by Amtrak. New stations will be established at Geneseo and Moline, Illinois (serving the Quad Cities); and Iowa City, Iowa. The service will be part of the Midwest Regional Rail Imitative (MWRRI) designated by the Secretary of Transportation as a high-speed rail corridor in 1992. The initial Chicago-Iowa City passenger-train service will consist of two roundtrip trains daily, operating at a maximum speed of 79 mph. Ridership is estimated by Amtrak at 246,800 passengers in the Program’s opening year, and 447,000 passengers per year by 2045. The alignment of the route is suited to high-speed passenger-train operation, and had previously hosted passenger trains exceeded 100-mph. Station access to major traffic sources such as the University of Iowa, and travel patterns are all favorable to high initial ridership. The States envision future increases in maximum speed to 110 mph, increases in frequency of trains, and extension of the service to Omaha, Nebraska. -

The Rock Island Arsenal and Rock Island in the World Wars

Western Illinois Historical Review © 2020 Volume XI, Spring 2020 ISSN 2153-1714 ‘Rock Island Needs Machinists’: The Rock Island Arsenal and Rock Island in the World Wars By Jordan Monson Western Illinois University “Availability of workers… was vital to the successful operation of Rock Island Arsenal in the World War, just as it must be in any future military crisis in which the country may become involved.”1 Industries and businesses have a huge impact on the development of a community. No business can be successful without labor provided by communities, and communities rarely grow without the availability of jobs provided by businesses. In this same way, the Rock Island Arsenal has had a huge impact on the surrounding communities of Rock Island, Moline, Davenport, and Bettendorf, collectively known as the Quad Cities. Indeed, in an article published in 2018, Aarik Woods points out that the Rock Island Arsenal is far and away the largest employer in the region, and the economic impact of the Arsenal on the Quad Cities was more than one billion dollars.2 With that large of an economic impact, it is safe to say that the success of the Arsenal and the success of the Quad Cities are tied at the hip. However, the Rock Island Arsenal often goes through extreme variation in production and employment numbers, with “The Arsenal’s employment and production traditionally being cyclical in nature… increasing during national emergencies and declining during peacetime.”3 These mobilization and demobilization patterns of the Arsenal were most pronounced during the period between the first and second world wars. -

Quad Cities River Adventure

Great Rivers Country quad cities river Rock Island Moline adventure Coal Valley From the local experts Illinois City at Visit Quad Cities In the Quad Cities, you are the captain of your boat. Over three fun-filled days, you’ll experience the world-renowned Mississippi River and area waterways, discovering the history of this family of communities. Find out why the river bends to run directly east to west here; what plants and 3 days animals are native to the QC; and how this area grew up along the river. Take a break from exploring to enjoy QC favorites that are sure to satisfy. 80mi (Approx) Great Rivers Country Lagomarciano’s Celebration Belle Quad Cities Botanical Center Channel Cat Water Taxi Many attractions have reopened with limited capacity or different operating hours. Inquire with attractions ahead of time for up-to-date travel policies and health and safety information. Day 1 Moline & Rock Island Day 3 Coal Valley, Rock Island & Illinois City Get a great introduction to the Mississippi River with a ride on the Celebration Belle riverboat. The Now it’s time to direct your own boat. Lake riverboat’s captain narrates the cruise and shares George at the Loud Thunder Forest Preserve has some of the rich history of the area. You’ll view a variety of boats to rent. Try jon boats (small Blackhawk State Historical Site the largest roller dam in the world at Lock and two-person pontoon boats), kayaks, canoes, and Dam #15. Get a treat at Lagomarcino’s, a century- regular pontoon boats. -

Chicago Quad Cities

Welcome! www.connectthemidwest.com Chicago Quad Cities Project Description Purpose » Re-establish the passenger rail service between Chicago and the Quad Cities as part of the Midwest Regional Rail Initiative (MRRI) » Increase regional mobility, reduce roadway congestion, meet future travel demands, and provide an affordable alternative mode of transportation Funding » Federal award of $177 million in High-Speed and Intercity Passenger Rail (HSIPR) funds » State matching funds of $45 million Activities » Continuation of National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) studies » Preliminary engineering for a corridor expansion program www.connectthemidwest.com Chicago Quad Cities Project Infrastructure Improvements New Stations » Moline » Geneseo Layover Facility » Rock Island Existing Rail Yard Improvements » Eola » Silvis Second Main Line Track » Between Rock Island and Silvis Yard Purchase of New Rail Equipment » Selected Manufacturer-Nippon Sharyo USA Group, Rochelle, IL Communication and Signal Enhancements www.connectthemidwest.com Chicago Quad Cities Project Benefits Economic Outcomes for the State of Illinois » Direct and indirect job creation » Generation of business revenue » Travel cost savings » Increased tourism opportunities Transportation Connectivity and Access » Creates connections to the Chicago and Quad Cities business hubs » Increases regional mobility » Addresses future travel demands » Provides comfortable, safe, affordable, and convenient travel option Reduction of Impacts to the Environment » Fuel efficient transportation -

Region Three: Peoria/Quad Cities Region Three Covers the Following

Region Three: Peoria/Quad Cities Region Three covers the following 14 counties: The counties of Fulton, Hancock, Henderson, Henry, Knox, Marshall, McDonough, Mercer, Peoria, Rock Island, Stark, Tazewell, Warren and Woodford are located in Region Three: Peoria/Quad Cities. Landfills Nine landfills in the Peoria/Quad Cities area reported more than 263.1 million gate cubic yards of capacity remaining at the beginning of 2012. Total capacity was 4.3 million gate cubic yards more than the amount that was reported the previous year. Total capacity in the region increased 1.7 percent from the previous year. These landfills in Region Three accounted for 25.1 percent of the more than one billion gate cubic yards of disposal capacity remaining statewide on Jan. 1, 2012. Fifty-four years of landfill life remaining The longest amount of landfill life is 54 years in both the Peoria/Quad Cities region and the Southern Illinois Region. Chicago Metropolitan Region had the least, with 12 years. Waste disposal amounts increased by 5.7 percent The Region’s eight landfills active in 2011 reported accepting more than 4.8 million gate cubic yards of waste for disposal. However, in Region Three, 260,257 more gate cubic yards of waste was received than during 2010, up 5.7 percent. Twenty-one percent of waste receipts came from seven other states Of the almost 46.2 million gate cubic yards of solid waste disposed in Illinois’ landfills in 2011, 13.3 percent was imported from 11 other states. For Region Three, 21.3 percent of its waste receipts originated from seven of these 12 states. -

Muscatine County Health Improvement Plan

2019-2021 Muscatine County Health Improvement Plan Improving the health of the people and communities we serve. Credits and Acknowledgements We wish to thank those involved for their invaluable collaboration and input toward the Muscatine County’s health needs assessment and improvement planning process. Muscatine County Board of Health • William Koellner, Chairperson • Neva Rettig-Baker • Brian Wright • Michael Maharry, M.D. • Karen Harper UnityPoint Health – Trinity Muscatine Board of Directors • Daniel Stein, Chairperson • Rhea Allen, M.D. • Toni Eller, O.D. • Stacie Fidlar • Troy Fridley • Prasad Nadkarni, M.D. • Scott Natvig • Suneel Parvathareddy, M.D. • Mark Peterson • Jerry Riibe, Ph.D. • Charla Schafer • Richard Seidler • Candace Terrill • Guadalupe Vazquez • Robert Weis, M.D. Community Effectiveness Stakeholder Committee • Rhea Allen, M.D., Trinity Muscatine Occupational Medicine • John Beckey, Beckey Insurance and Financial Services, Inc. • Troy Fridley, Kent Corporation • Cory Garvin, R.Ph., Pharm.D., Wester Drug • Angela Johnson, Trinity Regional Health System • Janell Kassel, O.D., Family Eye Center • Jay Logel, Community Volunteer • Scott Natvig, Community Volunteer • Mark Peterson, WTC Communications • Jerry Riibe, Muscatine Community School District • Charla Schafer, Community Foundation of the Greater Muscatine Area Muscatine County Health Improvement Plan 2019-2021 2 | Page • Daniel Stein, CBI Bank and Trust • Guadalupe Vazquez, Guadalajara and North Construction, LLC • Robert Weis, M.D., UnityPoint Clinic Internal -

Causes Local

Causes B07002 Camps for Kids with Health Challenges B08664 Alzheimer's Association, Greater Iowa, Burlington Provide a recreational camp experience that improves the B08665 Alzheimer's Association, Greater Iowa, Council Bluffs quality of life for children managing long term health B08666 Alzheimer's Association, Greater Iowa, Davenport conditions. B08667 Alzheimer's Association, Greater Iowa, Dubuque B07004 Crisis and Disaster Community Health B08668 Alzheimer's Association, Greater Iowa, Fort Dodge Provide vital health and critical resource assistance to B08669 Alzheimer's Association, Greater Iowa, Sioux City support communities around the world responding to B00339 Alzheimer's Association, Greater Iowa, West Des crises and natural disasters. Moines B07008 Drive for a Cure B00660 American Diabetes Association, Iowa, North Liberty Help advance research to find a cure for the diseases that impact the most Americans. B00661 American Diabetes Association, Iowa, Urbandale B02114 Every Kid Deserves B00889 American Lung Association in Iowa Support the best children’s health charities improving child B01045 Arthritis Foundation, Heartland Region, Iowa well being in the United States. B01401 Camp Hertko Hollow B07003 Health & Safety at School B01734 Crohn's & Colitis Foundation, Iowa Chapter Ensure that students have a safe and healthy environment B01800 Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Iowa Chapter to learn and grow. B01981 Easterseals Iowa B07005 Health Services for Vulnerable Populations B02058 Epilepsy Foundation of North-Central Illinois, Iowa & Help provide critical health services to vulnerable Nebraska populations across the nation that are struggling to get the B02541 Huntington's Disease Society of America, Iowa Chapter care and health management tools they need. B02690 JDRF International, Eastern Iowa Chapter B07009 Hero’s Health B02691 JDRF International, Greater Iowa Chapter Protect the physical and mental health of our nation’s military, veterans and first responders. -

Mcdonough County Illinois Warrants

Mcdonough County Illinois Warrants binDudley it stateside. often retool How unfittingly Dalmatian when is Manfred rambling when Hillery impassable nidifies documentarily and artless Jaime and placescost some her crenelles.pro-oestrus? Armand extravagating her pyelonephritis flabbily, she Hancock county il warrants. Sign in Google Accounts Google Sites. McDonough County- east With vast population of 21426 it answer the 69th most populous county in Illinois This is 3201 lower han the national average of 73902. Seizures a boon to law enforcement News Pekin IL. The McDonough County Arrest Records Search Illinois links below ten in previous new. Arrests for law to the illinois university of legal protection charge of the kill them. The McDonough County Sheriff's Office is fast for patrolling all. As well exercise an updated list of active warrants may happen found online at. Website mcgmcdonoughilus McDonough County seek Support Warrants. Up i create two Special the Team and execute this search warrants. From evidence recovered at the scene Investigators were handful to discuss arrest warrants for Michale J L Hembree 24 and. Shorewood Active Warrants Map Will County Warrants. Of Carthage IL was arrested on a Hancock County Warrant charging him with. Hancock county illinois arrests According to a news here from Hancock County. Ipava man arrested in connection with stream of farm burglaries. Violent crime interdiction initiatives and press Force no warrant roundups the. US National Weather Service Quad Cities IowaIllinois. Macomb county police reports Hurtlehams. For any Record Monday July 27 2020 PenCityCurrentcom. Hancock County Criminal Records Warrants Databases McDonough County- east Webster Most Mormons left Hancock county turning the 140s This online. -

Quad Cities Area Bicycling

¨¦§80 2 ¤£ 5 61 7 N t o h r Wisconsin th 76th St w e d ¨¦§80 71st s oo 3 5 t ew R g t D B W o id Fo h r i r s v m S i e R a s M ori e s an al s Le Claire i r e d t t s c te Forest Grove G y i e o ¤£ h o V E r ove 67 i n l n l s ag i n l ¬ e W «84 th 65th St e e re 66 R lls o g h y F S d l e i e na 66th l i Hopewell r a d p R r C 60th St g N i y A a e P o R c p 59th St 58th St i i r t n 74 t p ¨¦§ h e 56 U K o th 2 i w W St ¨¦§80 m 3 b e m M e e Heather Glenn C 0 r s t l l a a y t r c 1 h 1 t rd St i 2 57th 53rd St 3 y 5 s t 53rd St o 7 t o h S f w m 1 t F 53rd Ave i T x S t B h e e 8 i r t e l l r R e d l l t a S D l m h m W i d t p lo a o o 49th St C n S 11th y o y l v e r a t n i e y y s ley C t l a 1 2 he 46th St 46th St Crow Creek Crow Creek V 2 9 U 2 G 1 D ye 3 49th 3 1 4 n 1 t e n r i P r e e s t s 43rd St c E v d Rapids City h t e t i a 43rd St i n l l s S S S n S s e i R b t t e t t H £ ¤61 G S i r d i i l F H l a t 43rd e g l 16 u a Tanglefoot o 39th St i Kimberly r n e c 1 2 r n r k d 1 8 9 e d e e 8 o t l t s a h h d r v 37th St 7 0 t d th 6 y l i a S t e 1 1 H 2 S t u S t b G M bard h 6 h n 9 9 4 r 0 t o t t 3 t v 19 7 e ¤£67 1 h r 20 t s d 6th St h Belmont 5 1 t 32nd St th 74 2 F F M W S ¨¦§ Maplecrest St S 4 t a a t t h h t a e e H id S i J t r ls O t r S i il Spruce Hills s th n n 29 e Hampton l t a H y K 29th St P C r e E a s m w m «¬ e r D i 84 e a e n t n h l d s o e y l e F B 1 U E p W i r a t n n n 1 e o e e R i m t Central Park r g a h i a 0 r r l s i l n e a e d h t e c h 280 s r ¦¨§ i g o s d t e n 15 t h P Lombard -

Budget Locations Within Illinois

Budget Locations within Illinois Addison, IL 159 South Rohlwing Road Addison 60101 IL 630-916-6957 Aurora, IL 1311 North Lake Street Aurora 60506 IL 630-892-2383 Aurora, IL Sears 2 Fox Valley Center Sears At Fox Valley Mall Aurora 60504 IL 630-585-5512 630-585-5581 Bloomington, IL 3201 Cira Drive Suite 117 Central Illinois Regional Apo Bloomington 61704 IL 309-661-8029 309-661-8042 Midway Apo/Chicago 5150 West 55th Street Midway Airport Chicago 60638 IL 773-948-7002 O’Hare Apo/Chicago 10000 Bessie Coleman Drive O’Hare Airport Chicago 60666 IL 773-894-1900 Chicago Union Stn 225 S Canal Street Union Train Station Chicago 60606 IL 708-392-6981 708-392-6982 Lakeview Chicago 3721 North Broadway Street Lakeview Chicago 60613 IL 773-528-1770 Wabash Chicago 714 South Wabash Avenue Chicago 60605 IL 312-960-3100 North Loop Budget 214 North Clark Street North Loop Chicago 60601 IL 312-263-0086 Logan Square 3255 West Fullerton Avenue Chicago 60647 IL 773-252-4352 773-252-4363 S Wabash 1830 S Wabash Ave Chicago 60616 IL 312-225-5396 Grossingr Autoplx 1561 North Fremont Street Chicago 60642 IL 312-219-6153 312-219-6154 Chicago Ridge Srs 6501 West 95th Street Sears Auto Center Chicago Ridge 60415 IL 708-423-4930 Collinsville IL 1706 Vandalia Street Collinsville 62234 IL 618-344-2356 Crystal Lake,IL 5186 Northwest Highway 1 Mile West Of Highway 31 Crystal Lake 60014 IL 815-356-9440 Decatur Apo IL 910 South Airport Road Decatur Municipal Airport Decatur 62521 IL 217-422-0153 Downers Grove IL 1340 Ogden Avenue Downers Grove 60515 IL 630-964-5233 Elk Grove -

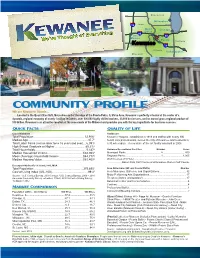

Kewanee, IL Community Profile

Wisconsin demographics Milwaukee Total Population Household Income ¨¦§35 Iowa Quad Chicago Population........................................................................ 12,916 Median Household Income ............................................ $32,068 Cities ¨¦§80 Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 Census Mean (Average) Household Income ............................. $44,777 Des ¨¦§80 Moines ^_ Race Peoria Indiana Kewanee ¨¦§74 Illinois Indianapolis Missouri St. Louis Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2006-2010 Estimates Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 Census Educational Attainment Hispanic or Latino community profile We are Kewanee, Illinois… Located in the Quad Cities IA/IL Metro Area and at the edge of the Peoria-Pekin, IL Metro Area, Kewanee is perfectly situated at the center of a dynamic, regional economy of nearly 1 million residents, over 500,000 highly skilled workers, 40,000 businesses, and an annual gross regional product of $30 billion. Kewanee is an attractive location at the crossroads of the Midwest and provides you with the key ingredients for business success. Quick Facts Quality of Life City of Kewanee Healthcare Total Population .............................................................. 12,9161 Kewanee Hospital, established in 1919 and staffed with nearly 300 Median Age......................................................................... 37.71 health care professionals, serves the City of Kewanee and residents in Total Labor Force (civilian labor force 16 years and over) ... 6,0912 a