3. Islam and Healing 30 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

Political Phenomena in Barak-Surma Valley During Medieval Period Dr

প্রতিধ্বতি the Echo ISSN 2278-5264 প্রতিধ্বতি the Echo An Online Journal of Humanities & Social Science Published by: Dept. of Bengali Karimganj College, Karimganj, Assam, India. Website: www.thecho.in Political Phenomena in Barak-Surma Valley during Medieval Period Dr. Sahabuddin Ahmed Associate Professor, Dept. of History, Karimganj College, Karimganj, Assam Email: [email protected] Abstract After the fall of Srihattarajya in 12 th century CE, marked the beginning of the medieval history of Barak-Surma Valley. The political phenomena changed the entire infrastructure of the region. But the socio-cultural changes which occurred are not the result of the political phenomena, some extra forces might be alive that brought the region to undergo changes. By the advent of the Sufi saint Hazrat Shah Jalal, a qualitative change was brought in the region. This historical event caused the extension of the grip of Bengal Sultanate over the region. Owing to political phenomena, the upper valley and lower valley may differ during the period but the socio- economic and cultural history bear testimony to the fact that both the regions were inhabited by the same people with a common heritage. And thus when the British annexed the valley in two phases, the region found no difficulty in adjusting with the new situation. Keywords: Homogeneity, aryanisation, autonomy. The geographical area that forms the Barak- what Nihar Ranjan Roy prefers in his Surma valley, extends over a region now Bangalir Itihas (3rd edition, Vol.-I, 1980, divided between India and Bangladesh. The Calcutta). Indian portion of the region is now In addition to geographical location popularly known as Barak Valley, covering this appellation bears a historical the geographical area of the modern districts significance. -

Optimizing Uses of Gas for Industrial Development: a Study on Sylhet, Bangladesh by Md

Global Journal of Management and Business Research: A Administration and Management Volume 15 Issue 7 Version 1.0 Year 2015 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-4588 & Print ISSN: 0975-5853 Optimizing Uses of Gas for Industrial Development: A Study on Sylhet, Bangladesh By Md. Asfaqur Rahman Pabna University of Science and Technology, Bangladesh Abstract- Proper and planned industrialization for any country can help to earn its expected GDP growth rate and minimize the unemployment rate. Industrial sector basically consists of manufacturing, together with utilities (gas, electricity, and water) and construction. But all these components to establish any industry are not available concurrently that only guarantee Sylhet. Here this study is conducted to identify the opportunities to generate the potential industrial sectors into Sylhet that ensures the proper utilization of idle money, cheap labor, abundant natural gas, and other infrastructural facilities. This industrialization process in Sylhet will not only release from the hasty expansion of industries into Dhaka, Chittagong but also focuses it to be an imminent economic hub of the country. As a pertinent step, this study analyzed the trend of gas utilization in different sectors and suggests the highest potential and capacity for utilizing gas after fulfilling the demand of gas all over the country. Though Sylhet has abundant natural resources and enormous potentials for developing gas-based industries, it has also some notable barriers which could easily be overcome if all things go in the same horizontal pattern. This paper concludes with suggestions that Sylhet could undertake the full advantage of different gas distribution and transmission companies and proposed Special Economic Zone (SEZ) as well for sustaining the momentum. -

Sylhet Division

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Sylhet Division Includes ¨ Why Go? Sylhet ..............127 Pastoral Sylhet packs in more shades of green than you’ll Ratargul ............130 possibly find on a graphic designer’s shade card. Blessed Sunamganj .........131 with glistening rice paddies, the wetland marshes of Ratar- gul and Sunamganj, the forested nature reserves of Lowa- Srimangal & Around .............131 cherra, and Srimangal’s rolling hills blanketed in waist-high tea bushes, Sylhet boasts a mind-blowing array of land- scapes and sanctuaries that call out to nature lovers from around the world. Even while offering plenty of rural adventures for those Best Places willing to go the extra mile, Sylhet scores over several other to Sleep divisions in terms of its easy accessibility. Good transport links mean Sylhet’s famous tea estates, its smattering of Ad- ¨ Nishorgo Nirob Ecoresort ivasi mud-hut villages, its thick forests and its serene bayous (p136) are all just a few hours’ drive or train journey from Dhaka. ¨ Nazimgarh Garden Resort Given its relaxed grain, Sylhet is best enjoyed at leisure. (p127) Schedule a week at least for your trip here, especially if you ¨ Grand Sultan Tea Resort love outdoor activities. (p137) When to Go Best Places to Eat Sylhet Rainfall inches/mm ¨ Panshi Restaurant (p129) °C/°F Te mp 40/104 ¨ Woondaal (p129) 24/600 30/86 ¨ Kutum Bari (p137) 16/400 20/68 8/200 10/50 0/32 0 J FDM A M J J A S O N Mar–Nov Oct–Mar Dry Mar–May If Tea-picking season; time for Dhaka is too hot, season. -

RRP: Natural Gas Access Improvement Project (Bangladesh)

Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors Project Number: 38164 February 2010 Proposed Loans People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Natural Gas Access Improvement Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 15 January 2010) Currency Unit – Taka (Tk) Tk1.00 = $0.0145 $1.00 = Tk68.03 In this report, a rate of $1 = Tk70.00 is used. ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ADF – Asian Development Fund BERC – Bangladesh Energy Regulatory Commission BGFCL – Bangladesh Gas Fields Company Limited BGSL – Bakhrabad Gas Systems Limited CNG – compressed natural gas DPP – development project pro forma DSR – debt service ratio EIRR – economic internal rate of return EMRD – Energy and Mineral Resources Division FIRR – financial internal rate of return FNPV – financial net present value GSRR – gas sector reform road map GTCL – Gas Transmission Company Limited GTDP – Gas Transmission and Development Project ICB – international competitive bidding IEE – initial environmental examination IMRS – interface metering and regulating station IOC – international oil company JICA – Japan International Cooperation Agency LIBOR – London interbank offered rate OCR – ordinary capital resources Petrobangla – Bangladesh Oil, Gas, and Mineral Corporation QCBS – quality- and cost-based selection ROR – rate of return SCADA – supervisory control and data acquisition SGC – state-owned gas company SGCL – Sundarban Gas Company Limited TA – technical assistance TGTDCL – Titas Gas Transmission and Distribution Company Limited USAID – United States Agency for International Development WACC – weighted average cost of capital WEIGHTS AND MEASURES BCF – billion cubic feet ha – hectare km – kilometer m3 – cubic meter MMCFD – million cubic feet per day MW – megawatt TCF – trillion cubic feet NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the government and the Bangladesh Oil, Gas, and Mineral Corporation group of companies ends on 30 June. -

140102 Final Value Chian Report Sylhet Region

Study Report on Selection and Analysis of Value Chains (Final) For North East Region January 06, 2014 USAID’s Climate-Resilient Ecosystems and Livelihoods (CREL) Component 4: Improve and diversified livelihoods that are environmentally sustainable and resilient to Climate Change Winrock International Acknowledgment This report is produced by Innovision Consulting Private Limited for review by the Climate Resilient Ecosystems and Livelihoods (CREL) project, the lead implementer of which is Winrock International. The report is done under purchase order number CREL-INNO-005. The views expressed in the report are of Innovision and its consultants and not necessarily of CREL, Winrock International or USAID. Innovision Consulting Private Limited would like to thank USAID and Winrock-CREL project for providing us the opportunity to undertake the study. We would like to acknowledge the support provided by Mr. Darrell Deppert, Chief of Party, CREL, especially for his valuable advice and suggestions at the inception phase of the study. We are also very thankful to Mr. Mahmud Hossain, Livelihood Manager, CREL and his team for their valuable guidelines on the design and implementation of the study and also for their relentless supports throughout the study. Thanks to Mr. Abul Hossain and Mr. P.K. Pasha for their support. We are very grateful to the regional coordinators, Mr. Sheikh Md. Ziaul Huque of Khulna, Mr. Mazharul Islam Zahangir of Srimangal, Mr. Narayan Chandra Das of Chittagong and Mr. Md. Safiqur Rahman of Cox‟s Bazar, for their constant and wholehearted cooperation throughout the study period. We are very thankful to the livelihood officers of the four regions of CREL project for their valuable suggestions in the planning, coordination and strong presence in the field investigation. -

Project: Chhatak Road and Drain Package 1

Final Initial Environmental Examination December 2015 BAN: Third Urban Governance and Infrastructure Improvement (Sector) Project-Chhatak Road and Drain Package 1 UGIIP-III-I/CHHA/UT+DR/01/2014/Lot1(UT)&Lot2(DR) Prepared by the Local Government Engineering Department, Government of Bangladesh for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of December 2015) Currency Unit = BDT BDT1.00 = $0.0127 $1.00 = BDT78.525 ABRREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AP – affected person DoE – Department of Environment DPHE – Department of Public Health Engineering EARF – environmental assessment and review framework ECA – Environmental Conservation Act ECC – environmental clearance certificate ECR – Environmental Conservation Rules EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan ETP – effluent treatment plant GRC – grievance redressal cell GRM – grievance redress Mechanism IEE – initial environmental examination LCC – location clearance certificate LGED – Local Government Engineering Department MLGRDC – Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development, and Cooperatives O&M – operations and maintenance PMO – project management office PPTA – project preparatory technical assistance REA – rapid environmental assessment RP – resettlement plan SPS – Safeguard Policy Statement ToR – terms of reference WEIGHTS AND MEASURES ha – hectare km – kilometre m – meter mm – millimetre GLOSSARY OF BANGLADESHI TERMS crore – 10 million (= 100 lakh) ghat – boat landing station hartal – nationwide strike/demonstration called by opposition parties khal – drainage ditch/canal khas, khash – belongs to government (e.g. land) katcha – poor quality, poorly built lakh, lac – 100,000 madrasha – Islamic college mahalla – community area mouza – government-recognized land area parashad – authority (pourashava) pourashava – municipality pucca – good quality, well built, solid thana – police station upazila – sub district NOTES (i) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. -

People's Republic of Bangladesh Preparatory Survey on Renewable

People’s Republic of Bangladesh Infrastructure Development Company Limited (IDCOL) People’s Republic of Bangladesh Preparatory Survey on Renewable Energy Development Project Final Report November 2012 Japan International Cooperation Agency Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. 4R JR(先) 12-039 “PREPARATORY SURVEY ON RENEWABLE ENERGY DEVELOPMENT PROJECT” <Final Report> Prepared for: JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT COMPANY LIMITED (IDCOL) Prepared by: MITSUBISHI RESEARH INSTITUTE, INC. Submitted to JICA November 2012 Table of Contents 1. Overview of JICA-REDP ...................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Background ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Features of JICA-REDP ................................................................................................... 2 2. Deployment Status of Renewable Energy (RE) and Energy Efficiency and Conservation (EE&C) Technologies in Bangladesh.................................................................................... 5 2.1. Overview of Energy Sector in Bangladesh ...................................................................... 5 2.1.1. Energy Balance....................................................................................................... 5 2.1.2. Power Generation ................................................................................................... 6 2.1.3. Renewable -

Introducing the Sylheti Language and Its Speakers, and the SOAS Sylheti Project

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 18. Editors: Candide Simard, Sarah M. Dopierala & E. Marie Thaut Introducing the Sylheti language and its speakers, and the SOAS Sylheti project CANDIDE SIMARD, SARAH M. DOPIERALA & E. MARIE THAUT Cite this article: Simard, Candide, Sarah M. Dopierala & E. Marie Thaut. 2020. Introducing the Sylheti language and its speakers, and the SOAS Sylheti project. In Candide Simard, Sarah M. Dopierala & E. Marie Thaut (eds.) Language Documentation and Description 18, 1-22. London: EL Publishing. Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/196 This electronic version first published: August 2020 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Introducing the Sylheti language and its speakers, and the SOAS Sylheti project Candide Simard The University of the South Pacific Sarah M. Dopierala Goethe University Frankfurt E. Marie Thaut SOAS, University of London Abstract Sylheti is a minoritised, politically unrecognised, and understudied Eastern Indo-Aryan language with approximately 11 million speakers worldwide, with high speaker concentrations in the Surma and Barak river basins in north-eastern Bangladesh and south Assam, India, and in several diasporic communities around the world (especially UK, USA, and Middle East). -

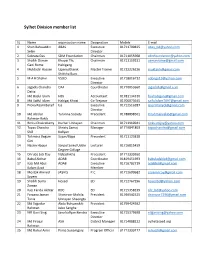

Sylhet Division Member List

Sylhet Division member list SL Name organization name Designation Mobile E-mail 1 Shah Bahauddin ABAS Executive 01711700825 [email protected] Selim Director 2 Subrata Das SDM Foundation Chairman 01711055908 [email protected] 3 Shaikh Osman Khoyai Thi, Chairman 01711159231 [email protected] Gani Rume Habigang 4 Muktadir Hossen Upanusthanik Master Trainer 01722226226 [email protected] Shikkha Buro 5 M A H Shahin VSDO Executive 01718016712 [email protected] Director 6 Jagadis Chandra OAF Coordinator 01770053660 [email protected] Datta 7 Md Bajlul Islam HBS Accountant 01781134310 [email protected] 8 Md Saiful Islam Habigaj Khoai Co-Trejarar 01706073645 [email protected] 9 Prova Raani Baraif Isa Executive 01712516287 [email protected] Director 10 Md Abidur Tarunna Society Precedent 01788898501 [email protected] Rahman Rakib 11 Rinku Chakrabarty Durbar Unnayan Chairman 01711910941 [email protected] 12 Tapas Chandra Shristy Samaj Manager 01719841803 [email protected] Shill Kollyan 13 Tahmina Begum Sujon/Bapa Precedent 01711123818 Gini 14 Nasrin Haque Saiyad Soied Uddin Lecturer 01716815459 Degree Collage 15 Dhruba Joti Day Nabashikha Precedent 01712330260 16 Babul Akthar ADAB Coordinator 01819451693 [email protected] 17 Kazi Md Abul ADAB Executive 01716782719 [email protected] Kalam Azad Member 18 Mostak Ahmed JASHIS P.C 01712600682 [email protected] Sayem 19 Shaikh Suma Hosed ED 01712767296 [email protected] Zaman 20 Kazi Farida Akhtar RDC ED 01715358239 [email protected] 21 Farzana Jaman Shonirvor -

Data Collection Survey on Bangladesh Natural Gas Sector FINAL REPORT

Ministry of Power, Energy and Mineral Resources The People’s Republic of Bangladesh Data Collection Survey on Bangladesh Natural Gas Sector FINAL REPORT January 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. SAD JR 12-005 Ministry of Power, Energy and Mineral Resources The People’s Republic of Bangladesh Data Collection Survey on Bangladesh Natural Gas Sector FINAL REPORT January 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. Source: Petrobangla Annual Report 2010 Abbreviations ADB Asian Development Bank BAPEX Bangladesh Petroleum Exploration & Production Company Limited BCF Billion Cubic Feet BCMCL Barapukuria Coal Mine Company Limited BEPZA Bangladesh Export Processing Zones Authority BERC Bangladesh Energy Regulatory Commission BEZA Bangladesh Economic Zone Authority BGFCL Bangladesh Gas Fields Company Limited BGSL Bakhrabad Gas Systems Limited BOI Board of Investment BPC Bangladesh Petroleum Corporation BPDB Bangladesh Power Development Board CNG Compressed Natural Gas DWMB Deficit Wellhead Margin for BAPEX ELBL Eastern Lubricants Blenders Limited EMRD Energy and Mineral Resources Division ERD Economic Related Division ERL Eastern Refinery Limited GDP Gross Domestic Product GEDBPC General Economic Division, Bangladesh Planning Commission GIZ Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GOB Government of Bangladesh GTCL Gas Transmission Company Limited GTZ Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Technische Zusammenarbeit GSMP Gas Sector Master Plan GSRR Gas Sector Reform Roadmap HCU Hydrocarbon -

Problems and Prospects of Tourism Industry in Bangladesh: a Study on Cumilla District

South Asian Journal of Social Studies and Economics 10(4): 27-35, 2021; Article no.SAJSSE.64585 ISSN: 2581-821X Problems and Prospects of Tourism Industry in Bangladesh: A Study on Cumilla District S. M. Nazrul Islam1* and Sk. Rahima Akter1 1Department of Business Administration, Noakhali Science and Technology University, Noakhali, Bangladesh. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between both authors. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/SAJSSE/2021/v10i430271 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Angel Paniagua Mazorra, Spanisch Council for Scientific Research, Spain. (2) Dr. John M. Polimeni, Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, USA. (3) Dr. Ridzwan Che Rus, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, Malaysia. Reviewers: (1) Ravindra L.W. Koggalage, University of Vocational Technology, Sri Lanka. (2) S. R. Dastane, Savitribai Phule Pune University, India. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/64585 Received 15 November 2020 Original Research Article Accepted 20 January 2021 Published 19 May 2021 ABSTRACT Tourism is one of the most growing industries all around the world. Bangladesh is a new tourist destination on the map of the world. Bangladesh has enormous potential to develop tourism because of its attractive natural beauty and rich cultural heritage. The tourism industry of Bangladesh has several positive impacts on the overall economy of this country. Tourism can add value to the Bangladeshi economy if a proper marketing plan and strategy can be built and implemented for this purpose. The main objective of the study was to find out the major problems and prospects of the tourism industry in Bangladesh.