Manuel V. Pepsi-Cola Company

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protein (G) Sodium (Mg) BRISK ICED TEA & LEMONADE 110 0 28 27 0 60

ROUNDED NUTRITION INFORMATION FOR FOUNTAIN BEVERAGES Source: PepsiCoBeverageFacts.com [Last updated on January 11, 2017] Customer Name: GPM Investmments, LLC Other Identifier: Nutrition information assumes no ice. 20 Fluid Ounces with no ice. Total Carbohydrates Calories Total Fat (g) (g) Sugars (g) Protein (g) Sodium (mg) BRISK ICED TEA & LEMONADE 110 0 28 27 0 60 BRISK NO CALORIE PEACH ICED GREEN TEA 5 0 0 0 0 175 BRISK RASPBERRY ICED TEA 130 0 33 33 0 70 BRISK SWEET ICED TEA 130 0 36 36 0 80 BRISK UNSWEETENED NO LEMON ICED TEA 0 0 0 0 0 75 CAFFEINE FREE DIET PEPSI 0 0 0 0 0 95 DIET MTN DEW 10 0 1 1 0 90 DIET PEPSI 0 0 0 0 0 95 G2 - FRUIT PUNCH 35 0 9 8 0 175 GATORADE FRUIT PUNCH 150 0 40 38 0 280 GATORADE LEMON-LIME 150 0 40 35 0 265 GATORADE ORANGE 150 0 40 38 0 295 LIPTON BREWED ICED TEA GREEN TEA WITH CITRUS 180 0 49 48 0 165 LIPTON BREWED ICED TEA SWEETENED 170 0 45 45 0 155 LIPTON BREWED ICED TEA UNSWEETENED 0 0 0 0 0 200 MIST TWST 260 0 68 68 0 55 MTN DEW 270 0 73 73 0 85 MTN DEW CODE RED 290 0 77 77 0 85 MTN DEW KICKSTART - BLACK CHERRY 110 0 27 26 0 90 MTN DEW KICKSTART - ORANGE CITRUS 100 0 27 25 0 95 MTN DEW PITCH BLACK 280 0 75 75 0 80 MUG ROOT BEER 240 0 65 65 0 75 PEPSI 250 0 69 69 0 55 PEPSI WILD CHERRY 260 0 70 70 0 50 SOBE LIFEWATER YUMBERRY POMEGRANATE - 0 CAL 0 0 0 0 0 80 TROPICANA FRUIT PUNCH (FTN) 280 0 75 75 0 60 TROPICANA LEMONADE (FTN) 260 0 67 67 0 260 TROPICANA PINK LEMONADE (FTN) 260 0 67 67 0 260 TROPICANA TWISTER SODA - ORANGE 290 0 76 76 0 60 FRUITWORKS BLUE RASPBERRY FREEZE 140 0 38 38 0 40 FRUITWORKS CHERRY FREEZE 150 0 40 40 0 45 MTN DEW FREEZE 150 0 41 41 0 45 PEPSI FREEZE 150 0 38 38 0 25 *Not a significant source of calories from fat, saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, or dietary fiber. -

Global Journal of Business Disciplines

Volume 4, Number 1 Print ISSN: 2574-0369 Online ISSN: 2574-0377 GLOBAL JOURNAL OF BUSINESS DISCIPLINES Editor: Qian Xiao Eastern Kentucky University Co Editor: Lin Zhao Purdue University Northwest The Global Journal of Business Disciplines is owned and published by the Institute for Global Business Research. Editorial content is under the control of the Institute for Global Business Research, which is dedicated to the advancement of learning and scholarly research in all areas of business. Global Journal of Business Disciplines Volume 4, Number 1, 2020 Authors execute a publication permission agreement and assume all liabilities. Institute for Global Business Research is not responsible for the content of the individual manuscripts. Any omissions or errors are the sole responsibility of the authors. The Editorial Board is responsible for the selection of manuscripts for publication from among those submitted for consideration. The Publishers accept final manuscripts in digital form and make adjustments solely for the purposes of pagination and organization. The Global Journal of Business Disciplines is owned and published by the Institute for Global Business Research, 1 University Park Drive, Nashville, TN 37204-3951 USA. Those interested in communicating with the Journal, should contact the Executive Director of the Institute for Global Business Research at [email protected]. Copyright 2020 by Institute for Global Research, Nashville, TN, USA 1 Global Journal of Business Disciplines Volume 4, Number 1, 2020 EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD Aidin Salamzadeh Rafiuddin Ahmed University of Tehran, Iran James Cook University, Australia Daniela de Carvalho Wilks Robert Lahm Universidade Europeia – Laureate International Western Carolina University Universities, Portugal Virginia Barba-Sánchez Hafiz Imtiaz Ahmad University of Castilla-La Mancha, Spain New York Institute of Technology Abu Dhabi Campus Wei He Purdue University Northwest Ismet Anitsal Missouri State University H. -

BEVERAGE RUM SOFTDRINKS Bacardi Carta Blanca

BEVERAGE SOFTDRINKS RUM Pepsi, Diet Pepsi, Mirinda, 7 Up…………………………............15 Bacardi Carta Blanca.......................................................35 Malibu...............................................................................35 ﺑﻴﺒﺴﻲ ، داﻳﺖ ﺑﻴﺒﺴﻲ ، ﻣﻴﺮﻧﺪا، اﻟﺴﻔﻦ اب Diet Coke...........................................................................15 Mount Gay Eclipse..........................................................40 Captain Morgan Spiced Rum…………………………..…………...40 داﻳﺖ آﻮآﺎ آﻮﻻ Soda, Tonic, Ginger Ale....................................................15 Lemon Soda.......................................................................15 Lemon Mint......................................................................20 TEQUILA Iced Tea..…........................................................................20 Jose Cuervo Silver............................................................35 Red Bull, Red Bull sugar free.........................................30 Patron Silver……….............................................................50 CHILLED JUICES COCKTAILS AND MOCKTAILS Apple, mango, fruit cocktail, pineapple.......................20 STILL WATER HEALTHY BLENDS Al Ain 1.5 ltr…....................................................................15 Red Defender…………………………………………………………………….25 Acqua Panna (500 ml)…………...........................................15 Strawberries, red grapes, watermelon Acqua Panna 1 ltr…………...................................................25 Evian (500 ml)…...............................................................20 -

2019 Pepsi Beverages Portfolio

2019 PEPSI BEVERAGES PORTFOLIO PROUCT INFORMATION www.pepsiproductfacts.com CSD CRAFT SODA READY TO DRINK COFFEE Starbucks Frappuccino 20oz Bottles (24pk) 1893 from the Bundaberg 13.7oz Glass Bottles (12pk) 2L Bottles (8pk) Makers of Pepsi-Cola 375ML Glass Bottles (4pk) 12oz Cans (24pk) Vanilla Mocha 12oz Sleek Cans (12pk) Almond Milk Mocha Caramel Ginger Beer Pepsi Mountain Dew Almond Milk Vanilla Coffee Original Cola Root Beer Diet Pepsi Diet Mountain Dew White Chocolate Salted Dark Chocolate Ginger Cola Diet Ginger Beer Pepsi Zero Sugar Mountain Dew Ice Caramelized Honey Vanilla Pepsi Zero Sugar Cherry Mountain Dew Code Red Blood Orange Pepsi Real Sugar Mountain Dew Liv e Wire Guav a Pepsi Vanilla Real Sugar Mountain Dew Voltage Starbucks Latte Pepsi Wild Cherry Real Sugar Mountain Dew Throwback 14oz PET Bottle (12pk) Pepsi Cherry Vanilla Mountain Dew Whiteout Café Latte Pepsi Vanilla (New P1) Mountain Dew Pitch Black Vanilla Caffeine Free Pepsi Mountain Dew Baja Blast (LTO P3) Molten Chocolate Latte Caffeine Free Diet Pepsi Mug Root Beer ENERGY Salted Caramel Mocha Latte Wild Cherry Pepsi Crush Orange White Chocolate Mocha Latte Diet Wild Cherry Pepsi Crush Grape Mist Tw ist Crush Pineapple Mountain Dew Game Fuel (P3) Starbucks Smoothies Diet Mist Tw ist Schw eppes Ginger Ale Dr. Pepper Schweppes Seltzer Original 16oz Cans (12pk) 10oz Bottles (12pk) Dry Pepper Cherry Schw eppes Seltzer Black Cherry Charged Berry Blast Dark Chocolate ** Diet Dr. Pepper Schweppes Seltzer Lemon Lime Charged Cherry Burst Vanilla Honey Banana** Diet Dr Pepper Cherry Schw eppes Seltzer Raspberry Lime Charged Original Dew Charged Tropical Strike Starbucks Double Shot Energy 7.5oz Cans (24pk) Pepsi Pepsi Real Sugar 15oz Cans (12pk) Mocha Vanilla Diet Pepsi Dr. -

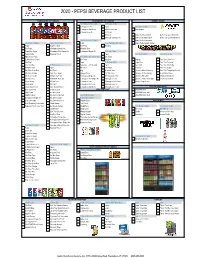

2020 - Pepsi Beverage Product List

2020 - PEPSI BEVERAGE PRODUCT LIST CARBONATED SOFT DRINKS CARBONATED SOFT DRINKS ENERGY DRINKS 10oz Glass Bottles (24pk) 16oz Cans (12pk) Schweppes Tonic Pepsi 16oz Cans (12pk) Schweppes Club Soda Wild Cherry Pepsi Amp Original Schweppes G. Ale Diet Pepsi Mtn.Dew Game Fuel Berry Blast Game Fuel Zero Watermln Schweppes Ginger Ale Game Fuel Original Dew Game Fuel Zero Rasp/Lmnd 12oz PET Bottles (3/8pk) Game Fuel Cherry Burst 20oz Bottles (24pk) 12oz Cans (2/12pk) Pepsi 16oz Aluminum Btl (12pk) Game Fuel Charged Orange Pepsi Mug Root Beer Diet Pepsi Mtn.Dew Diet Pepsi Schweppes Ginger Ale Mountain Dew Pepsi Zero Sugar Schweppes Diet Ginger Ale Schweppes Ginger Ale 1.25 Liter (12pk) Pepsi Vanilla Hawaiian Punch Pepsi 16oz Cans (24pk) 16oz Cans (24pk) Wild Cherry Pepsi 7.5oz Mini Cans 6pk(3/10pk*) Diet Pepsi Dt Wild Cherry Pepsi Diet Pepsi * Mtn.Dew Original Pure Zero Silver Ice Mist Twst Pepsi * 1L Bottles (15pk) Sugar Free Pure Zero Punched Mountain Dew 2L Bottles (8pk) Pepsi Zero - 3/10pk Only Pepsi Zero Carb Pure Zero Mand Org Diet Mtn Dew Pepsi Mtn. Dew * Diet Pepsi Punched Pure Zero Grape Mtn. Dew Code Red Diet Pepsi Mug Mountain Dew Xdurance Kiwi Strawberry Pure Zero Tang/Mng/Guv/Str Mtn. Dew Voltage Pepsi Zero Sugar Orange Crush Diet Mtn. Dew Xdurance Cotton Candy Revolt Killer Grape Mtn.Dew Livewire Wild Cherry Pepsi Schweppes Ginger Ale* Mtn.Dew Code Red Xdurance Blue-Raz Whipped Strawberry Mtn. Dew Zero Dt Wild Cherry Pepsi Schweppes Diet Ginger Ale Schweppes Tonic Xdurance Super Sour Apple Thermo Neon Blast Crush Orange Dt Pepsi Free Schweppes Tonic Schweppes Club Soda Thermo Tropical Fire Crush Grape Mist Twst Schweppes Diet Tonic Schweppes G. -

Table of Beverage Acidity (Ph Values Are Excerpted from Research Published in the Journal of the Americal Dental Association, 2016

Table of Beverage Acidity (pH values are excerpted from research published in the Journal of the Americal Dental Association, 2016. Other research sources may give slightly different pH values but erosiveness categories are similar.) Sodas Extremely Erosive pH below 3.0 7UP Cherry 2.98 Canada Dry Ginger Ale 2.82 Coco-Cola Caffeine Free 2.34 Coca-Cola Cherry 2.38 Coca-Cola Classic 2.37 Coco-Cola Zero 2.96 Dr. Pepper 2.88 Hawaiian Punch 2.87 Pepsi 2.39 Pepsi Max 2.39 Pepsi Wild Cherry 2.41 Schweppes Tonic Water 2.54 Erosive pH 3.0-4.0 7UP 3.24 Diet 7UP 3.48 Diet Coke 3.10 Dr. Pepper Cherry 3.06 Dr Pepper Diet 3.20 Mountain Dew 3.22 Mountain Dew Diet 3.18 Diet Pepsi 3.02 Sierra Mist Diet 3.31 Sierra Mist 3.09 Sprite 3.24 Sprite Zero 3.14 Minimally Erosive pH above 4.0 A&W Root Beer 4.27 A&W Root Beer Diet 4.57 Barq's Root Beer 4.11 Canada Dry Club Soda 5.24 Energy Drinks Extremely Erosive pH below 3.0 5-Hour Energy Extra Strength 2.82 5-Hour Energy Lemon-Lime 2.81 Jolt Power Cola 2.47 Rockstar Energy Drink 2.74 Rockstar Recovery 2.84 Erosive pH 3.0-4.0 Fuel Energy Shots Lemon-Lime 3.97 Fuel Energy Shots Orange 3.44 Jolt Ultra Sugar Free 3.14 Monster Energy 3.48 Monster Hitman Energy Shot 3.44 Monster Low Carb 3.60 Redbul Regular 3.43 Redbull Shot 3.25 Redbull Sugar Free 3.39 Rockstar Energy Cola 3.14 Rockstar Sugar Free 3.15 Waters and Sports Drinks Extremely Erosive pH below 3.0 Gatorade Frost Riptide Rush 2.98 Gatorade Lemon Lime 2.97 Gatorade Orange 2.99 Powerade Lemon Lime 2.75 Powerade Orange 2.75 Powerade Zero Lemon Lime 2.92 Powerade -

Coke Products 24/20 Oz. Pepsi Products 24/20 Oz

Page 1 PRODUCT DESCRIPTION PRODUCT DESCRIPTION COKE PRODUCTS 24/20 OZ. PEPSI PRODUCTS 24/20 OZ. CAFFIENE FREE DIET COKE BRISK LEMONADE CHERRY COKE BRISK ORANGEADE CHERRY COKE ZERO BRISK PINK LEMONADE CHERRY DR. PEPPER BRISK STRAWBERRY MELON COKE CAFFIENE FREE DIET PEPSI COKE ZERO CHERRY PEPSI DIET CHERRY DR. PEPPER CRUSH ORANGE DIET COKE CRUSH PINEAPPLE DIET COKE WITH LIME CRUSH STRAWBERRY DIET DR. PEPPER DIET CHERRY PEPSI DIET NESTEA LEMON DIET LIPTON GREEN TEA DIET SPRITE DIET PEPSI DR. PEPPER DIET SCHWEPPES GINGER ALE FANTA GRAPE DIET SIERRA MIST FANTA ORANGE HAWAIIAN PUNCH RED FANTA ORANGE ZERO LIPTON BRISK TEA FANTA PINEAPPLE LIPTON GREEN TEA FRESCA MOUNTAIN DEW ORIGINAL MELLO YELLOW MOUNTAIN DEW RED MINUTE MAID FRUIT PUNCH MOUNTAIN DEW VOLTAGE MINUTE MAID LEMONADE MUG CREAM MINUTE MAID PINK LEMONADE MUG ROOT BEER NESTEA LEMON PEPSI NESTEA POMAGRANATE SCHWEPPES BL. CHERRY SELTZER NESTEA RASPBERRY SCHWEPPES GINGER ALE POWERADE FRUIT PUNCH SCHWEPPES LEMON SELTZ POWERADE LEMON LIME SCHWEPPES ORANGE SELTZER POWERADE MOUNT. BLAST SCHWEPPES SELTZER POWERADE ORANGE SIERRA MIST POWERADE ZERO GRAPE WELCH'S GRAPE POWERADE ZERO MIXED BERRY POWERADE ZERO FRUIT PUNCH PEPSI PRODUCTS 24/12 OZ. CANS SEAGRAMS GINGER ALE CAFFIENE FREE DT. PEPSI SEAGRAMS SELTZER CAFFIENE FREE PEPSI SPRITE CHERRY PEPSI VANILLA COKE CRUSH ORANGE DIET CRUSH ORANGE COKE PRODUCTS 24/12 OZ. CANS DIET MOUNTAIN DEW CAFFIENE FREE COKE DIET PEPSI CAFFIENE FREE DIET COKE DIET SCHWEPPES GINGER ALE CHERRY COKE HAWAIIN PUNCH CHERRY COKE ZERO LIPTON BRISK TEA CHERRY DR. PEPPER MOUNTAIN DEW COKE ZERO PEPSI DIET DR. PEPPER SCHWEPPES GINGER ALE DIET SPRITE WELCH'S GRAPE DR. -

Standardized Residuals Can Be Applied to Any Table with Numbers

Standardized residuals can be applied to any table with numbers Column % 18 - 29 30 - 39 40 - 49 50 + Coca-Cola 55% 53% 28% 38% Diet Coke 3% 15% 14% 11% Coke Zero 16% 16% 23% 17% Pepsi 5% 8% 22% 6% Diet Pepsi 1% 0% 3% 6% Pepsi Max 18% 7% 11% 23% Which do you prefer Column % 18 - 29 30 - 39 40 - 49 50 + Column % 18 - 29 30 - 39 40 - 49 50 + Coca-Cola 55% 53% 28% 38% Coca-Cola 55% ↑ 53% ↑ 28% 38% Diet Coke 3% 15% 14% 11% Diet Coke 3% 15% 14% 11% Coke Zero 16% 16% 23% 17% Coke Zero 16% 16% 23% 17% Pepsi 5% 8% 22% 6% Pepsi 5% 8% 22% ↑ 6% Diet Pepsi 1% 0% 3% 6% Diet Pepsi 1% 0% 3% 6% Pepsi Max 18% 7% 11% 23% Pepsi Max 18% 7% 11% 23% ↑ Let’s explore residuals manually – to understand what they are • The coloured cells indicate a standardised residual that is Column % 18 - 29 30 - 39 40 - 49 50 + NET statistically significant (p<0.05) Coca-Cola 55% 53% 28% 38% 44% Diet Coke 3% 15% 14% 11% 11% • Look at the 22% for Pepsi and 40 – 49. Coke Zero 16% 16% 23% 17% 18% Pepsi 5% 8% 22% 6% 9% • This tells us that people aged 40 -49 3% are more likely to prefer Pepsi than Diet Pepsi 1% 0% 3% 6% are people in the other categories. Pepsi Max 18% 7% 11% 23% 16% sample size n=588 Computing the Expected % Counts 18 - 29 30 - 39 40 - 49 50 + TOTAL • We start with the raw Counts Coca-Cola 81 70 31 75 257 • Then, we compute the Total % Diet Coke 5 20 16 21 62 Coke Zero 24 21 25 34 104 • We start by computing 5 key numbers Pepsi 8 11 24 12 55 to understand Pepsi 40 - 49: Diet Pepsi 1 0 3 12 16 Observed % = 4% = 24 / 588 Pepsi Max 27 9 12 46 94 Column Total % = 19% TOTAL 146 131 111 200 588 Row Total % = 9% Total % 18 - 29 30 - 39 40 - 49 50 + TOTAL N = 588 Coca-Cola 14% 12% 5% 13% 44% Diet Coke 1% 3% 3% 4% 11% Coke Zero 4% 4% 4% 6% 18% And then the Expected % for that cell. -

2021 PEPSI BEVERAGES PORTFOLIO PROUCT INFORMATION – Products May Vary by Market/Location CSD CRAFTENERGY SODA READY to DRINK COFFEE

2021 PEPSI BEVERAGES PORTFOLIO PROUCT INFORMATION www.pepsiproductfacts.com – Products may vary by Market/Location CSD CRAFTENERGY SODA READY TO DRINK COFFEE 20oz Bottles (24pk) Bang Starbucks Frappuccino 2L Bottles (8pk) 16oz Cans (12pk) 13.7oz Glass Bottles (12pk) 12oz Cans (24pk) Blue Raspberry Miami Cola Vanilla Mocha Pepsi Mountain Dew Peach Mango Power Punch Almond Milk Mocha Caramel Diet Pepsi Diet Mountain Dew Cotton Candy Birthday Cake Bash Almond Milk Vanilla Coffee Pepsi Zero Sugar Mountain Dew Zero Sugar Rainbow Unicorn Key Lime Pie White Chocolate Salted Dark Chocolate Pepsi Zero Sugar Cherry Mountain Dew Real Sugar Star Blast Strawberry Blast Caramelized Honey Vanilla Pepsi Zero Sugar Vanilla Mountain Dew Code Red Sour Heads Purple Kiddles Brown Butter Caramel Pepsi Real Sugar Mountain Dew Watermelon **NEW** Black Cherry Vnl Citrus Twist Peppermint Mocha - LTO Pepsi Vanilla Mountain Dew Live Wire Purple Haze Champagne Pepsi Wild Cherry Mountain Dew Voltage Cherry Blade Lemonade Root Beer Blaze Starbucks Latte Starbucks NITRO - NEW Diet Wild Cherry Pepsi Mountain Dew Voo Dew Radical Skdtl Caffeine Free Candy Apple Crisp 14oz PET Bottle (12pk) 9.6oz Can (12pk) Caffeine Free Pepsi Mountain Dew Frost Bite Pina Colada Caffeine Free Birthday Cake Bash Café Latte Black Unsweetened Caffeine Free Diet Pepsi Mountain Dew White Out Citrus Froze Rose Caffeine Free Miami Cola Vanilla Latte Vanilla Sweet Cream Sierra Mist w/ Real Sugar Mug Root Beer Bangster Berry Caffeine Free Purple Guava Pear Molten Chocolate Latte Dark Caramel Diet Sierra Mist Crush Orange Purple Guava Pear Caffeine Free Black Cherry Vanilla Salted Caramel Mocha Latte Caffeine Free Sour Heads Sierra Mist Cranberry – LTO Crush Grape Candy Apple Crisp Caramel Macchiato Dr. -

New Pepsi Drink Contains Only One Calorie • FDA Approves

COMPANY NEWS New Pepsi Drink Contains Only One Calorie epsi One, a new drink by Pepsi- Diet Market Share Sugared Market Share P Cola Company, contains only one calorie. Pepsi-Cola Company announced 30% 78% the introduction of this drink minutes 28 after the FDA approved a new sugar- 76 substitute, acesulfame potassium. 26 74 The Pepsi-Cola Company said that Pepsi One, created specifically for the US 24 72 market, delivers the ideal offering for consumers who want it all — great cola taste with only one calorie. The drink 22 70 1990 '91 '92 '93 '94 '95 '96 '97 1990 '91 '92 '93 '94 '95 '96 '97 contains two sweeteners — acesulfame potassium and aspartame. Source: Beverage Digest "Anyone who used to think they were compromising taste by drinking a diet be taken off the market in the near future to use acesulfame potassium (also known soda will be blown away by the great because they "did not want to sacrifice as Sunett) in the US. new taste of Pepsi One," said Philip A that business or what they (the con- Marineau, President and CEO of Pepsi- In an interview with reporters, M Douglas sumers) want." Cola North America. Ivester, Coke's chairman and chief exe- A sizeable campaign to launch the brand cutive, called Diet Coke a "very powerful "Pepsi One will redefine the image of is impending and Pepsi agency PPDO brand" in the US and said he has no plans diet colas and revolutionize the entire soft Worldwide is developing radio and TV to reformulate the drink. -

Carbonated Beverages

2 LITER BOTTLES 20 OZ BOTTLES 1.25 LITER 12 PACK CANS 16OZ CANS 1 LITER PEPSI PEPSI PEPSI PEPSI PEPSI PEPSI DIET PEPSI DIET PEPSI DIET PEPSI DIET PEPSI DIET PEPSI DIET PEPSI CAFFEINE FREE PEPSI CAFFEINE FREE DIET PEPSI CAFFEINE FREE PEPSI WILD CHERRY PEPSI MOUNTIAN DEW CAFFEINE FREE DIET PEPSI WILD CHERRY PEPSI 16.9 OZ-6 PACK BOTTLES CAFFEINE FREE DIET PEPSI MOUNTAIN DEW DR PEPPER WILD CHERRY PEPSI DIET WILD CHERRY PEPSI PEPSI PEPSI ZERO MOUNTAIN DEW CODE RED GINGER ALE DIET WILD CHERRY PEPSI PEPSI ZERO DIET PEPSI WILD CHERRY PEPSI MOUNTAIN DEW ICE CLUB SODA PEPSI ZERO CRYSTAL PEPSI CAFFEINE FREE PEPSI DIET WILD CHERRY PEPSI GINGER ALE TONIC WATER MOUNTAIN DEW PEPSI CARAMEL WILD CHERRY PEPSI MOUNTAIN DEW ORANGE CRUSH DIET TONIC WATER DIET MOUNTAIN DEW MOUNTAIN DEW PEPSI ZERO DIET MOUNTAIN DEW PINEAPPLE SUNKIST ORIGINAL SELTZER MOUNTAIN DEW CODE RED DIET MOUNTAIN DEW ORANGE CRUSH MOUNTAIN DEW CODE RED DR PEPPER BLACK CHERRY SELTZER MOUNTAIN DEW VOLTAGE MOUNTAIN DEW CODE RED MOUNTAIN DEW MOUNTAIN DEW VOLTAGE LEMON LIME SELTZER MOUNTAIN DEW ICE MOUNTAIN DEW VOLTAGE DIET MOUNTAIN DEW MOUNTAIN DEW BAJA BLAST 16.9 OZ MOUNTAIN DEW CANS ORANGE SELTZER MIST TWIST MOUNTAIN DEW BAJA BLAST GINGER ALE MOUNTAIN DEW ARTIC BURST MOUNTAIN DEW BLACK LABEL RASBERRY LIME SELTZER DIET MIST TWIST MOUNTAIN DEW PITCH BLACK DIET GINGER ALE MOUNTAIN DEW TROPICAL SMASH MOUNTAIN DEW WHITE LABEL PINK GRAPEFRUIT SELTZER CRANBERRY MIST TWIST MOUNTAIN DEW WHITE OUT DR PEPPER MOUNTAIN DEW ICE MOUNTAIN DEW GREEN LABEL DIET CRANBERRY MIST TWIST MOUNTAIN DEW LIVEWIRE BRISK -

PEPSI-COLA COMPANY Beverage Catalogue for K -12 Schools 33

1 1 COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE MEETING JUNE 11, 2007 2 MILLARD PUBLIC SCHOOLS BOARD COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE The Board of Education Committee of the Whole will meet on Monday, June 11, 2007 at 7:00 p.m. at the Don Stroh Administration Center, 5606 South 147th Street. The Public Meeting Act is posted on the Wall and Available for Public Inspection Public Comments on agenda items - This is the proper time for public questions and comments on agenda items only. Please make sure a request form is given to the Board Vice-President before the meeting begins. AGENDA 1. LB 641 Power Point 2. Food Service/Soft Drink Policy Public Comments - This is the proper time for public questions and comments on any topic. Please make sure a request form is given to the Board Vice President before the meeting begins. 3 Minutes Committee of the Whole June 11,2007 The members of the Board of Education met for a Budget Retreat on Monday, June 11, 2007 at 7:00 p.m. at the Don Stroh Administration Center, 5606 South 147th Street. The evening agenda was a review of LB 641 and discussion of the food servicelsoft drink policy. PRESENT: Mike Kennedy, Mike Pate, Jean Stothert, Linda Poole, and Dave Anderson ABSENT: Brad Burwell Keith Lutz and Angelo Passarelli reviewed the Metro School Learning Community LB 641. They discussed and clarified the Learning Community timeline, the financial implications, the power of the local boards of education, the power of the Learning Community Coordinating Council (LCCC), and the Learning Community Achievement Council.