Saving Basquiat: Seeing the Art Through the Myth-Making at

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Patricia Faure, 2004 Nov. 17-24

Oral history interview with Patricia Faure, 2004 Nov. 17-24 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Patricia Faure on November 17, 22, 24, 2004. The interview took place in Beverly Hills, California, and was conducted by Susan Ehrlich for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Patricia Faure and Susan Ehrlich have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MS. SUSAN EHRLICH: This is Susan Ehrlich interviewing Patricia Faure in her home in Beverly Hills, California, on November 17, 2004, for the Archives of American Art of the Smithsonian Institution. This is Disc Number One, Side One. Well, let’s begin with your childhood, where were you born, when were you born, and tell me about your early life and experience? MS. PATRICIA FAURE: I was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin on April 8, 1928. I grew up there as well, went to school there, until I was 15, when we moved to Los Angeles, because after I was born, immediately after I was born, I got pneumonia. And I had pneumonia at least twice before I was six months old, and at one time the hospital called my parents and said to come and see me, for the last time. -

Schirn Presse Basquiat Boom for Real En

BOOM FOR REAL: THE SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT PRESENTS THE ART OF JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT IN GERMANY BASQUIAT BOOM FOR REAL FEBRUARY 16 – MAY 27, 2018 Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988) is acknowledged today as one of the most significant artists of the 20th century. More than 30 years after his last solo exhibition in a public collection in Germany, the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt is presenting a major survey devoted to this American artist. Featuring more than 100 works, the exhibition is the first to focus on Basquiat’s relationship to music, text, film and television, placing his work within a broader cultural context. In the 1970s and 1980s, Basquiat teamed up with Al Diaz in New York to write graffiti statements across the city under the pseudonym SAMO©. Soon he was collaging baseball cards and postcards and painting on clothing, doors, furniture and on improvised canvases. Basquiat collaborated with many artists of his time, most famously Andy Warhol and Keith Haring. He starred in the film New York Beat with Blondie’s singer Debbie Harry and performed with his experimental band Gray. Basquiat created murals and installations for New York nightclubs like Area and Palladium and in 1983 he produced the hip-hop record Beat Bop with K-Rob and Rammellzee. Having come of age in the Post-Punk underground scene in Lower Manhattan, Basquiat conquered the art world and gained widespread international recognition, becoming the youngest participant in the history of the documenta in 1982. His paintings were hung beside works by Joseph Beuys, Anselm Kiefer, Gerhard Richter and Cy Twombly. -

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT New York, NY 10014

82 Gansevoort Street JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT New York, NY 10014 p (212) 966-6675 allouchegallery.com Born 1960, Brooklyn, NY Died 1988, Manhattan, NY SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Boom for Real, Shirn exhibition hall, Frankfurt, Germany 2015 Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY 2015 Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now’s the Time, Art Gallery of Ontario, Ontario, Canada. Travelled to: Guggenheim Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain 2013 Jean-Michel Basquiat: Paintings and Drawings, Galerie Bruno Bischofberger, Zurich, Switzerland 2012 Warhol and Basquiat, Arken Museum of Modern Art, Ishøj, Denmark 2010 Jean-Michel Basquiat, The Fondation Beyeler, Basel, Switzerland. Traveled to: City Museum of Modern Art, Paris, France 2006 The Jean-Michel Basquiat show, Fondazione La Triennale di Milano, Milan, Italy 2006 Jean-Michel Basquiat 1981: The Studio of the Street, Deitch Projects, New York, NY 2005 Basquiat, Curated by Fred Hoffman, Kellie Jones, Marc Mayer, and Franklin Sirmans Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY Traveled to: Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX 2002 Andy Warhol & Jean-Michel Basquiat: Collaboration Paintings, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA 1998 Jean-Michel Basquiat: Drawings & Paintings 1980-1988, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA 1997 Jean-Michel Basquiat: Oeuvres Sur Papier, Fondation Dina-Vierny-Musée Maillol, Paris, France 1996 Jean-Michel Basquiat, Serpentine Gallery, London, England; Palacio Episcopal de Mágala, Málaga, Spain 1994 Jean-Michel Basquiat: Works in Black and White, -

Ed Ruscha Continues His Wordplay

The New York Times November 3, 2016 GAGOSIAN Ed Ruscha Continues His Wordplay Farah Nayeri In Ed Ruscha’s new canvases, on display at Gagosian in London, words are presented in logical sequences and in diminishing or augmenting typeface. Ed Ruscha, via Gagosian LONDON — Every week or so, Ed Ruscha drives for three hours from his home in Los Angeles to his cabin in the Californian desert. There, the artist engages in what he describes as “events of plain living” — fixing a faucet, feeding a bird, watering a neglected tree. “L.A. changes constantly, and the things that we all appreciated are not going to be there next week,” Mr. Ruscha said in an interview at the Gagosian Gallery in London, where he is showing 15 new works. “I like the no-change part of the desert.” That desert landscape seems to serve as a backdrop to many of the new canvases on display here (through Dec. 17). This is Gagosian’s first show of Ruscha paintings since an exhibition at its Rome gallery in 2014-15, and comes on the heels of the “Ed Ruscha and the American West” survey at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. Many of the new canvases hanging in London are the color of sand, and — as is the Ruscha trademark — covered with words. The novelty is that the words are presented in logical sequences and in diminishing or augmenting typeface. On one canvas, for example, the word “Galaxy” is inscribed in large letters at the top, followed in a pyramid of diminishing characters by “Earth,” “U.S.A.,” “State,” “City,” “Block,” “Lot” and “Dot.” “The new things are about micro and macro: from the smallest atom to the universe,” said Bob Monk, a Gagosian director who has known Mr. -

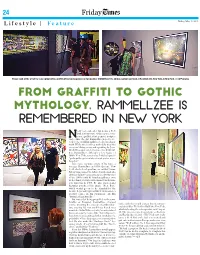

P24-25 Layout 1

24 Friday Lifestyle | Feature Friday, May 11, 2018 People look at the art of the conceptual artist, graffiti artist, hip-hop pioneer, Rammellzee (RAMMSLLZSS), during a private preview at Red Bull Arts New York, in New York. — AFP photos From graffiti to gothic mythology, Rammellzee is remembered in New York early a decade after his death, a New NYork retrospective of the rapper, com- poser, graffiti artist, painter, sculptor and cosmic theorist Rammellzee hopes to re- veal to the world his multifaceted, iconoclastic work. While street art has worked its way into everyone’s living room, and a painting by Jean- Michel Basquiat can fetch more that $100 mil- lion, Rammellzee, although a key figure of 1980s New York, remains-as Sotheby’s put it- ”perhaps the greatest street artist you’ve never heard of.” Like many aspiring artists of his time, a teenage Rammellzee in 1970s Queens, New York, started out spraying on subway trains. But as time passed, his letters transformed into abstract figures-compositions that by the start of the 1980s could be found in galleries, even Rotterdam’s prestigious Boijmans Van Beunin- gen museum in 1983. He also rapped-and Basquiat produced-his single “Beat Bop,” which would go on to be sampled by the Beastie Boys and Cypress Hill. Next, he made a stealthy cameo in Jim Jarmusch’s cult film “Stranger Than Paradise.” But instead of being propelled to the same heights as Basquiat, Rammellzee changed course-inventing the concept of gothic futur- rative arch that could convey his intentions,” ism, creating his own mythology based on a explained Max Wolf of Red Bull Arts New York, manifesto. -

Drawings from the Marron Collection to Be Copresented by Acquavella

Drawings from the Marron Collection to be copresented by Acquavella Galleries, Gagosian, and Pace Gallery at Pace’s space in East Hampton August 12–20, 2020 Pace Gallery, 68 Park Place, East Hampton, New York Ed Ruscha, Red Yellow Scream, 1964, tempera and pencil on paper, 14 3/8 × 10 3/4 inches (36.5 × 27.3 cm) © Ed Ruscha August , Acquavella Galleries, Gagosian, and Pace Gallery are pleased to announce a joint exhibition of works on paper from the esteemed Donald B. Marron Collection, belonging to one of the twentieth and twenty-first century’s most passionate and erudite collectors. The exhibition will be on view August –, , at Pace’s recently opened gallery in East Hampton, New York. In a continuation of the three galleries’ partnership with the Marron family to handle the sale of the private collection of the late Donald B. Marron, this intimate presentation offers a glimpse into the coveted Marron estate of over masterworks acquired over the course of six decades. The exhibition will feature almost forty works on paper including sketches and studies as well as fully realized paint and pastel pieces. Works on view range from early modern masterpieces by Henri Matisse, Raoul Dufy, and Fernand Léger; to nature studies by Ellsworth Kelly and an exemplary acrylic from Paul Thek’s final series; to contemporary pieces by Mamma Andersson, Leonardo Drew, Damien Hirst, Jasper Johns, and Brice Marden, among others. A focused presentation on Ed Ruscha’s typographic and image-based drawings and a selection of his inventive artist’s books will round out the exhibition. -

Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, No

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Peter R. Kalb, review of Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11870. Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation Curated by: Liz Munsell, The Lorraine and Alan Bressler Curator of Contemporary Art, and Greg Tate Exhibition schedule: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, October 18, 2020–July 25, 2021 Exhibition catalogue: Liz Munsell and Greg Tate, eds., Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, exh. cat. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2020. 199 pp.; 134 color illus. Cloth: $50.00 (ISBN: 9780878468713) Reviewed by: Peter R. Kalb, Cynthia L. and Theodore S. Berenson Chair of Contemporary Art, Department of Fine Arts, Brandeis University It may be argued that no artist has carried more weight for the art world’s reckoning with racial politics than Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988). In the 1980s and 1990s, his work was enlisted to reflect on the Black experience and art history; in the 2000 and 2010s his work diversified, often single-handedly, galleries, museums, and art history surveys. Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation attempts to share in these tasks. Basquiat’s artwork first appeared in lower Manhattan in exhibitions that poet and critic Rene Ricard explained, “made us accustomed to looking at art in a group, so much so that an exhibit of an individual’s work seems almost antisocial.”1 The earliest efforts to historicize the East Village art world shared this spirit of sociability. -

The World Is Finally Woke to Aboriginal Art: Sotheby's Move Its Sales From

The world is finally woke to Aboriginal art: Sotheby’s move its sales from London to the Big Apple amid increasing contemporary art world buzz. By Jane Raffan, on 28-May-2019 Having rebirthed its defunct Australian ‘outpost’[i] auctions in the mother country in 2015 to great success, Sotheby’s is now moving Aboriginal art sales to their New York headquarters. This announcement rides on a wave of recent high-profile visibility, critical success and reception to exhibitions of Aboriginal art in the city, the latest of which is actor/comedian/writer Steve Martin’s Aboriginal art collection, which is being showcased in Manhattan at Gagosian Gallery until 3 July. Sotheby’s is now moving Aboriginal art sales to their New York headquarters. This announcement rides on a wave of recent high-profile visibility, critical success and reception to exhibitions of Aboriginal art in the city, the latest of which is actor/comedian/writer Steve Martin’s Aboriginal art collection, which is being showcased in Manhattan at Gagosian Gallery until 3 July. (Image: Rick Wenner/For The Washington Post) The Gagosian exhibition of a work by Emily Kame Kngwarreye from the University of Virginia’s Kluge-Ruhe Museum amid the private collection of Steve Martin and Ann Stringfield[i] has caused a stir in contemporary art circles, and received a swag of positive critical press, including an eloquent piece in The New York Times championing the value of deconstructing colonisation through indigenous art and the importance of opacity in post-colonial discourse[ii], which has long been a key visual device of much Australian Aboriginal desert painting. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Voleine Amilcar, ITVS

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Voleine Amilcar, ITVS 415-356-8383 x 244 [email protected] Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected] For downloadable images, visit pbs.org/pressroom/ For the program companion website, visit pbs.org/independentlens/jean-michel-basquiat/ TAMRA DAVIS’S JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT: THE RADIANT CHILD TO PREMIERE ON INDEPENDENT LENS TUESDAY, APRIL 12, 2011 AT 10PM ON PBS Definitive Documentary on the Meteoric Rise and Fall of the Brilliant Young Artist (San Francisco, CA) Centered on a rare interview that director Tamra Davis shot with her friend and contemporary Jean-Michel Basquiat over 20 years ago, Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child is the definitive chronicle of the short but brilliant life of the young artist who revolutionized the New York art scene almost overnight. Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child will premiere on the Emmy® Award-winning PBS series Independent Lens, hosted by America Ferrera, on Tuesday, April 12, 2011 at 10 PM (check local listings). The film is part of an April Art Month lineup, which also includes The Desert of Forbidden Art, Waste Land, and Marwencol. Told through interviews with his fellow artists, friends, and lovers, including Julian Schnabel, Larry Gagosian, Bruno Bischofberger, Fab 5 Freddy, Suzanne Mallouk, and Kenny Scharf, the film recounts Basquiat’s lightning-quick ascension from street kid to art world star. In the gritty, crime-ridden city that was New York in the late 1970s, artists, punk rockers, and writers flourished in the grimy oasis of the East Village. -

FUTURA2000 (Born Leonard Hilton Mcgurr in New York City) Is a Graffiti Pioneer Who Began Painting Subways in the Late 1970S

FUTURA2000 (born Leonard Hilton McGurr in New York City) is a graffiti pioneer who began painting subways in the late 1970s. In 1980 he painted the iconic whole car titled “Break,” which was recognized for its abstraction, rather than a focus on lettering. This painting established some of the enduring aesthetic motifs and approaches FUTURA2000 would explore over the decades that followed. FUTURA2000 was among the first graffiti artists to be shown in contemporary art galleries in the early 1980s. His paintings were shown at Patti Astor’s Fun Gallery and Tony Shafrazi, alongside those of his friends Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Rammellzee, DONDI, and Kenny Scharf. MoMA PS1 brought the artists together in their landmark 1981 exhibition, “New York / New Wave.” In this period, FUTURA2000 illustrated the sleeve cover for The Clash’s ‘This is Radio Clash’ seven-inch single. He accompanied The Clash on their Combat Rock tour, spray painting in the background while the band played. He painted as an accompaniment to demonstrations of break dance by the Rock Steady Crew, and concerts by Grand Master Flash and Afrika Bombataa. With the Clash, he recorded the vinyl “The Escapades of Futura 2000,” a manifesto for graffiti. By the 1990s, as the commercialization of global street culture in the 1990s inspired collaborations with fashion and lifestyle brands, FUTURA2000’s work moved toward a more refined expression of his abstract style. Commissions from brands such as Supreme, A Bathing Ape, Stüssy, and Mo' Wax saw his artwork canonized as an elemental component of cross-genre street aesthetic. He has collaborated with Nike, BMW, Comme des Garçons, Louis Vuitton, and Off-White. -

Hip Hop Music to Enhance Critical Discussions

HipHip Hop Hop Using Hip Hop Music to Enhance Critical Discussions JEFFREY L. BROOME MCs kick rhymes to beats, or a cappella Graf artists tagging year round through all weather Our culture’s evolving, what next will it bring Hip-hop is one of my favorite things DJs, b-boys, and b-girls are so clever They called it a fad, but we’re hip-hop forever We love our culture, to it we shall cling Hip-hop is one of my favorite things (Substantial, 2008, track 7) As an adolescent during the late 1980s and early 1990s, a favorite secondary art students could identify these links too. The purpose of activity among my peers was to listen to hip-hop music. We were this article is to detail my resulting instructional experiences using fascinated by this fairly new addition to popular culture (partially hip-hop music as a tool for enhancing critical discussions on post- because older generations told us it wasn’t “real music”), enjoyed modern art. I begin with a literature review on postmodernism and most of it, but never discussed it critically. All of that changed for on sampling in hip-hop music, before detailing my efforts in incor- me when friends played the song “The Magic Number” (Huston, porating hip-hop into my own collegiate instruction. A concluding Mercer, Jolicoeur, Mason, & Dorough, 1990) by De La Soul. I imme- section discusses the applicability of such methods at the secondary diately recognized parts of the tune and adapted lyrics from a short level and other implications for art education. -

Basquiat Boom for Real February 16 – May 27 2018

FILMING AND PHOTOGRAPHY – IMPORTANT GUIDELINES BASQUIAT BOOM FOR REAL FEBRUARY 16 – MAY 27 2018 Please ensure that you read and adhere to the following conditions: PHOTOGRAPHY IN THE EXHIBITION: IMPORTANT: Photography is not permitted in: o Sections “The Scene“, “Warhol“ and “Beat Bop“: no photography of any objects OR photography on loan from The Andy Warhol Foundation (see attached list) o Section “The Screen“: no photography of excerpt on TV „State of the Art“ o Section “Downtown 81“: Film “Downtown 81“ may only appear in background shots All images may only be used for current coverage of the exhibition. Their use for commercial purposes and the disclosure to third parties without further permission is prohibited. All works must be photographed in the context of the exhibition. No close up shots of individual works allowed. The images may not be changed in any significant way. All caption information must appear whenever an image is reproduced: Basquiat. Boom for Real Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt February 16 – May 27, 2018 Artworks: © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2018 & The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Licensed by Artestar, New York. Press installation images are available from the Newsroom: http://www.schirn.de/en/m/press/newsroom/basquiat_boom_for_real/#images FILMING IN THE EXHIBITION IMPORTANT: Filming is not permitted in: o Sections “The Scene“, “Warhol“ and “Beat Bop“: no filming of any objects OR photography on loan from The Andy Warhol Foundation (see attached list) o Section “The Screen“: no filming of excerpt on TV „State of the Art“ o Section “Downtown 81“: Film “Downtown 81“ may only appear in background shots All recordings may only be used for current coverage of the exhibition.