The Black Commodity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, No

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Peter R. Kalb, review of Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 7, no. 1 (Spring 2021), doi.org/10.24926/24716839.11870. Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation Curated by: Liz Munsell, The Lorraine and Alan Bressler Curator of Contemporary Art, and Greg Tate Exhibition schedule: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, October 18, 2020–July 25, 2021 Exhibition catalogue: Liz Munsell and Greg Tate, eds., Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, exh. cat. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2020. 199 pp.; 134 color illus. Cloth: $50.00 (ISBN: 9780878468713) Reviewed by: Peter R. Kalb, Cynthia L. and Theodore S. Berenson Chair of Contemporary Art, Department of Fine Arts, Brandeis University It may be argued that no artist has carried more weight for the art world’s reckoning with racial politics than Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988). In the 1980s and 1990s, his work was enlisted to reflect on the Black experience and art history; in the 2000 and 2010s his work diversified, often single-handedly, galleries, museums, and art history surveys. Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation attempts to share in these tasks. Basquiat’s artwork first appeared in lower Manhattan in exhibitions that poet and critic Rene Ricard explained, “made us accustomed to looking at art in a group, so much so that an exhibit of an individual’s work seems almost antisocial.”1 The earliest efforts to historicize the East Village art world shared this spirit of sociability. -

Parallel Tracks: Three Case Studies of the Relationship Between Street Art and U.S. Museums in the Twenty-First Century

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 11-2-2018 Parallel Tracks: Three Case Studies of the Relationship between Street Art and U.S. Museums in the Twenty-First Century Erin Rolfs Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Art Practice Commons, Museum Studies Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Recommended Citation Rolfs, Erin, "Parallel Tracks: Three Case Studies of the Relationship between Street Art and U.S. Museums in the Twenty-First Century" (2018). LSU Master's Theses. 4835. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4835 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 11-2-2018 Parallel Tracks: Three Case Studies of the Relationship between Street Art and U.S. Museums in the Twenty-First Century Erin Rolfs Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Art Practice Commons, Museum Studies Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons PARALLEL TRACKS THREE CASE STUDIES OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN STREET ART AND U.S. MUSEUMS IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Erin Rolfs B.A., Louisiana State University, 2006 December 2018 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................ -

Saving Basquiat: Seeing the Art Through the Myth-Making at

Saving Basquiat: Seeing the Art Through the Myth-Making at ... http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/886916/saving-basqui... Search All, Venues, Artists Submit Saving Basquiat: Seeing the Art Through the Myth-Making at Gagosian by Ben Davis Published: April 5, 2013 With over 50 Jean-Michel Basquiat / Courtesy of ITVS / Lee Jaffe paintings, “museum-quality” is probably the © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery. Photography by Robert term you'd use to describe Gagosian’s Jean-Michel McKeever Basquiat show, which has been drawing rock-star Installation view of the Jean-Michel Basquiat exhibition at Gagasion, West 24th Street, New York crowds to West 24th street since it opened. But really, it might be better to call it “warehouse-quality.” The show is overwhelming and difficult to write about, partly because there doesn’t seem to be any idea behind it at all; the works are hung neither by chronology nor by theme. They are merely a spectacularly impressive collection of largish Basquiats from a number of private collections. In this way, the show replicates the tragedy of this artist’s short and chaotic life, where the feverish buzz of celebrity came to overpower any assessment of the works as individual objects. Basquiat’s art is brimming with life — he worked fast, and painted everywhere, on everything around him — and it owes much of his continued cachet to the enduring legend of its unfiltered immediacy. But if you look closely, what you will see is that they are records, almost every one, of an almost crippling self-consciousness. -

124 Talents Portrait

124 TALENTS PORTRAIT GRAFFITIART #40 SEPTEMBRE/OCTOBRE 2018 125 TOXIC Templier des temps modernes — TEXTE / ÉLODIE CABRERA Acteur emblématique du graffiti new-yorkais dans les années 80, Toxic reste malgré son impressionnant pedigree relativement méconnu du grand public. Ce disciple de Rammellzee construit depuis près de quarante ans une œuvre insolente, puissante et cosmique qui s’inspire du passé mais regarde résolument vers l’avenir. Né en 1965 de parents caribéens, Torrick Ablack a Près de quarante ans plus tard, Toxic se réclame poussé dans un terreau fait de cendres et de fulgu- toujours du Futurisme Gothique (baptisé ainsi par rances. Le Bronx, au mitan des années 70. Dans les Rammellzee dans son manifeste datant de 1979), mais rues, les mômes des Savages Skulls dépouillaient en l’explore en solitaire. « Jean (Basquiat) et Rammellzee meute les malheureux égarés. Derrière les immeubles auraient 58 ans aujourd’hui, A-One, 54, Dondi, 57, en ruine, presque écroulés, les blocks parties voyaient égrène-t-il comme on lirait les dates sur un mémorial. le jour et le hip-hop faisait tourner les têtes. On se Je n’ai pas fait d’école d’art, mais je suis fortuné de disait breaker, dj, toaster, graffeur… Une contrecul- les avoir eus pour amis et mentors. C’étaient tous des ture était en train de naître sans se douter qu’elle génies. » Sous forme de collage, leurs dessins peuplent deviendrait un courant artistique capital, majeur du les toiles de Toxic. Comme des repères spatiotempo- XXIe siècle. « Nous avions 12 ou 13 ans, on taguait rels. Des grigris déposés ci et là au milieu d’un magma dans la rue, incognito. -

RESEARCH DEGREES with PLYMOUTH UNIVERSITY Gold Griot

RESEARCH DEGREES WITH PLYMOUTH UNIVERSITY Gold Griot: Jean-Michel Basquiat Telling (His) Story in Art by Lucinda Ross A thesis submitted to Plymouth University In partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Humanities and Performing Arts Doctoral Training Centre May 2017 Gold Griot: Jean-Michel Basquiat Telling (His) Story in Art Lucinda Ross Basquiat, Gold Griot, 1984 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. Gold Griot: Jean-Michel Basquiat Telling (His) Story in Art Lucinda Ross Abstract Emerging from an early association with street art during the 1980s, the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat was largely regarded within the New York avant-garde, as ‘an exotic other,’ a token Black artist in the world of American modern art; a perception which forced him to examine and seek to define his sense of identity within art and within society. Drawing upon what he described as his ‘cultural memory,’ Basquiat deftly mixed together fragments of past and present, creating a unique style of painting, based upon his own experiences of contemporary American life blended with a remembering of an African past. This study will examine the work of Basquiat during the period 1978 – 1988, tracing his progression from obscure graffiti writer SAMO© to successful gallery artist. Situating my study of Basquiat’s oeuvre in relationship to Paul Gilroy’s concept of the Black Atlantic, I will analyse Basquiat’s exploration of his cultural heritage and depiction of a narrative of Black history, which confronts issues of racism and social inequality, and challenges the constraints of traditional binary oppositions. -

The Life and Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat

PERFORMING BLACKNESS AT THE HEART OF WHITENESS: THE LIFE AND ART OF JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT Christopher F. Johnston A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2008 Committee: Andrew Hershberger, Advisor Irina Stakhanova Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen Berry Khani Begum © 2008 Christopher F. Johnston All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrew Hershberger, Advisor Born in Brooklyn, New York in 1960 to a Haitian father and a Puerto Rican mother, Jean-Michel Basquiat rose to prominence as a painter in the 1980s art world. When he died in 1988 at age twenty-seven from a drug overdose, he had achieved more fame and wealth than any black artist in history; he remains today the world’s most recognizable black painter. This study seeks to show how Basquiat’s racial and cultural background shaped his life and art. In its first three chapters, this study examines Basquiat’s experiences in New York City in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s in a variety of contexts including his neighborhoods, schools, the graffiti movement, avant-gardism, and the art world. This study finds that the artist’s blackness often made him racially hyper-visible and the target of racism and stereotyping. It also finds that of all the artistic traditions that Basquiat was exposed to and involved in, his experiences with performance art had the most enduring impact on him artistically. In its final two chapters, this study looks at Basquiat’s public persona and art. Chapter Four covers the way the artist walked, talked, dressed, wore his hair, acted in interviews, posed for photographs, and behaved in public in general. -

New York City Graffiti Murals: Signs of Hope, Marks of Distinction Patrick Verel [email protected]

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Urban Studies Masters Theses Urban Studies 2013 New York City Graffiti Murals: Signs of Hope, Marks of Distinction Patrick Verel [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/urban_studies_masters Recommended Citation Verel, Patrick, "New York City Graffiti Murals: Signs of Hope, Marks of Distinction" (2013). Urban Studies Masters Theses. 11. https://fordham.bepress.com/urban_studies_masters/11 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Urban Studies at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Studies Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW YORK CITY GRAFFITI MURALS: SIGNS OF HOPE, MARKS OF DISTINCTION By: Patrick Verel B.S., St. John’s University, 1997 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE URBAN STUDIES PROGRAM AT FORDHAM UNIVERSITY NEW YORK May 2013 2 Table of Contents 1. Acknowledgements 3 2. Abstract 4 3. Introduction 4 4. Theoretical Framework 6 5. Interdisciplinary Focus 12 6. A Brief History of Graffiti 16 7: Methodology 17 8. Case Study Manhattan 20 9. Case Study Brooklyn 25 10. Case Study The Bronx 34 11. Case Study Jersey City 42 12. Case Study Staten Island 51 13. Case Study Trenton 61 14. Philadelphia Mural Arts 69 15. NYC Mural Makers 75 16. Graffiti Free New York 81 17. The Clean Slate Fan 86 18. Five Pointz 90 19. Conclusion 100 20. Bibliography 103 21. Appendix I: NYC Anti Graffiti Laws 108 22. -

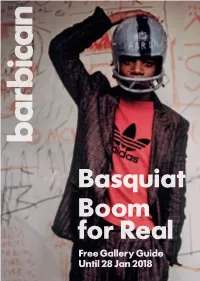

Basquiat Boom for Real

Basquiat Boom for Real Free Gallery Guide Until 28 Jan 2018 Exhibition curated by Dieter Buchhart and Eleanor Nairne and organised in cooperation with Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt (16 Feb – 27 May 2018) Discover more about Basquiat: Boom for Real at barbican.org.uk/explorebasquiat #BoomForReal Supported by Art Fund Front cover: Edo Bertoglio. Jean-Michel Basquiat wearing an American football helmet, 1981 Photo: © Edo Bertoglio, courtesy of Maripol Artwork: © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat Licensed by Artestar, New York Basquiat: Boom for Real Jean-Michel Basquiat was one of the most significant artists of the 20th century. Born in Brooklyn in 1960, to a Haitian father and a Puerto Rican mother, he grew up amid the post-punk scene in lower Manhattan. After leaving school at 17, he invented the character ‘SAMO©’, writing poetic graffiti that captured the attention of the city. He exhibited his first body of work in the influential group exhibition New York/New Wave at P.S.1, Institute for Art and Urban Resources, Inc., in 1981. When starting out, Basquiat worked collaboratively and fluidly across media, making poetry, performance, music and Xerox art as well as paintings, drawings and objects. Upstairs, the exhibition celebrates this diversity, tracing his meteoric rise, from the postcard he plucked up the courage to sell to his hero Andy Warhol in SoHo in 1978 to one of the first collaborative paintings that they made together in 1984. By then, he was internationally acclaimed – an extraordinary feat for a young artist with no formal training, working against the racial prejudice of the time. -

Contemporary Street Art As a Form of Political Aggravation and Protest

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses Undergraduate Theses 2019 Reclaiming Cities and Spatial Citizenship: Contemporary Street Art as a Form of Political Aggravation and Protest Morgan K. Quigg The University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/castheses Recommended Citation Quigg, Morgan K., "Reclaiming Cities and Spatial Citizenship: Contemporary Street Art as a Form of Political Aggravation and Protest" (2019). UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses. 61. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/castheses/61 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reclaiming Cities and Spatial Citizenship: Contemporary Street Art as a Form of Political Aggravation and Protest By Mo Quigg Contents: Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter One: A Brief History of Street Art…………………………………………………….5 Chapter Two: American Chief and Opaqe…………….……………………………………….19 Chapter Three: Culture Vultures and Social Activism……………………………...………...32 Chapter Four: Santiago “Cabaio” Spirito and Spatial Reclamation………………………...47 Chapter Five: Freeman Alley, Signature, and Public Spaces…………………………………60 Conclusions……………………………………………………………………………………...73 1 Introduction People have been writing on walls as long as the human race has existed, from the caves of Sulawesi to the streets of Pompeii to the subways of New York.1 Street art and graffiti culture as it exists today, however, originated in Philadelphia in 1967 before spreading to New York City by train.2 From here, the rest of the world caught on, and the movement reached every urban corner of the planet. -

Andy Warhol 'Jean-Michel Basquiat'

Basquiat Boom for Real 2 Introduction 4 New York New Wave 9 SAMO© 11 Canal Zone 14 The Scene 19 Downtown 81 21 Beat Bop 24 Warhol 27 Self Portrait 30 Bebop (Wall) 34 Bebop (Vitrine) 35 Art History (Vitrine) 37 Art History (Wall) 40 Encyclopaedia (Wall) 49 Encyclopaedia (Vitrine) 51 Notebooks 53 The Screen 58 Interview Jean-Michel Basquiat was one of the most significant artists of the 20th century. Born in Brooklyn in 1960, to a Haitian father and a Puerto Rican mother, he grew up amid the post-punk scene in lower Manhattan. After leaving school at 17, he invented the character ‘SAMO©’, writing poetic graffiti that captured the attention of the city. He exhibited his first body of work in the influential group exhibition New York/New Wave at P.S.1, Institute for Art and Urban Resources, Inc., in 1981. When starting out, Basquiat worked collaboratively and fluidly across media, making poetry, performance, music and Xerox art as well as paintings, drawings and objects. Upstairs, the exhibition celebrates this diversity, tracing his meteoric rise, from the postcard he plucked up the courage to sell to his hero Andy Warhol in SoHo in 1978 to one of the first collaborative paintings that they made together in 1984. By then, he was internationally acclaimed – an extraordinary feat for a young artist with no formal training, working against the racial prejudice of the time. In the studio, Basquiat surrounded himself with source material. He would sample from books spread open on the floor and the sounds of the television or boom box – anything worthy of his trademark catchphrase ‘boom for real’. -

Deblackboxing Basquiat by Coloring His Decade of Fame

Gamson 1 CCTP802: Deblackboxing the Valuation of “Art” Carly Gamson FIGURE 2: DEBLACKBOXING BASQUIAT BY COLORING HIS DECADE OF FAME What I hope to make clear through the timeline below is that factors outside of the properties of the artwork itself -- scale, medium/materials, subject matter, composition, etc. -- are absolutely necessary to understanding, rationalizing, and predicting the value ascribed to Basquiat’s artwork -- both as an artist on the whole as well as specific artworks within his oeuvre. The information below is largely adopted from a timeline provided by the Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. I have condensed the Estate’s timeline, extracted relevant details, and incorporated a system of color- coding. 1960: ● Basquiat is born in Park Slope, Brooklyn of Haitian and Puerto Rican heritage. Father Gerard Basquiat was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti; Mother Matilde Andradas was born in Brooklyn of Puerto Rican parents. 1978: ● Basquiat leaves home ● Basquiat and Al Diaz - close friend, fellow graffiti artist, and co-conspirator - form a street art collaboration and operate under the pseudonym SAMO. ● Basquiat begins spending time at the Mudd Club, a community of artists, musicians, and actors who come to define the alternative culture of the Lower East Side. 1979: ● SAMO IS DEAD: Basquiat and Diaz split up. Gamson 2 ● Basquiat makes money by selling t-shirts and making postcards that have a highly expressionist, graffiti-esque aesthetic. Themes around popular culture, including baseball players, Kennedy assassination, and mass consumerism, characterize his early works. ● Basquiat meets Keith Haring and Kenny Scharf at Club 57; Haring and Basquiat immediately become good friends and remain close.