Impunity and Political Accountability in Nepal Impunity and Political Accountability in Nepal in Accountability Political and Impunity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banking on Lessons 10 VIEWPOINT : Shivanth Pande' & Santosh Pokharel 11 FACE to FACE :Dr Bipin Adhikari 15 FORUM:Kamal Maden 19

· ~.. .... .... "' \ "' .j( $! u 15 ~ i : lU ~ ~ i ~ · -jH.~u ~ 1 I~t:~ ·~t 1~ 1l - · SPOT L IG H 'NEWSMAGAZINE • Page 16 QUOTE UNQUOTE 2 BRIEFS 3 NEWSNOTES 4 COALITION PARTNERS: Divided They Stand 7 POLITICAL INSTABILITY: Hampering Development 9 NOB'S FAILURE: Banking On Lessons 10 VIEWPOINT : Shivanth Pande' & Santosh Pokharel 11 FACE TO FACE :Dr Bipin Adhikari 15 FORUM:Kamal Maden 19 FORUM:Mohan Das Manandhar & Rojan Bajracharya 21 PROFILE : CHANDA RANA 22 ARTICLE: SB Pun 23 INTERVIEW- Sujata Koirala Page 12 OPINION: Qiu Guhong, Chinese ambassador to Nepal 24 Editor and Publisher : Keshab Poudel, Copy Editor: Ben Peterson Marketing Manager : Madan Raj Poudel, Photographer : Sandesh Manandhar Cover Design/Layout: Hari Krishna Bastakoti Editorial Office: Phone/Fax: 977-1-4602807, E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Office : Newplaza, Putalisadak, Tel: 4421846 Printers: Pioneer Offset Printers (P.) Ltd., Dillibazar, Kathmandu. Ph: 4415687 COO Regd. No. 148/063/64 NEW SPOTLIGHT NEWSMAGAZINE I June 16-20091 1 QUOTE UNQUOTE "I am ready to swallow all the bitterness they can spit at me. I will continue to advocate cooperation and unity." Prime Minister Madhav Kumar Nepal at the constant condemnation hurled at him by the Maoists. "The Nepali Congress and Unified Marxist Leninist are responsible for plotting to split our party." Upendra Yadav, chainnan of Madhesi Janadhikar Forum (MJF), accusing NC and UML of conspiring to divide the party by inciting a section of MJF leaders. "This government will fall within three month. Prachanda, Chairman UCPN Maoist. "There are consipirators within the party, who are more dangerious Jhalanath Khanal, Chairman CPN UML "Ours is a genuine Madbeshi Party. -

Country Report February 2004

Country Report February 2004 Nepal February 2004 The Economist Intelligence Unit 15 Regent St, London SW1Y 4LR United Kingdom The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit is a specialist publisher serving companies establishing and managing operations across national borders. For over 50 years it has been a source of information on business developments, economic and political trends, government regulations and corporate practice worldwide. The Economist Intelligence Unit delivers its information in four ways: through its digital portfolio, where the latest analysis is updated daily; through printed subscription products ranging from newsletters to annual reference works; through research reports; and by organising seminars and presentations. The firm is a member of The Economist Group. London New York Hong Kong The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit 15 Regent St The Economist Building 60/F, Central Plaza London 111 West 57th Street 18 Harbour Road SW1Y 4LR New York Wanchai United Kingdom NY 10019, US Hong Kong Tel: (44.20) 7830 1007 Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 Tel: (852) 2585 3888 Fax: (44.20) 7830 1023 Fax: (1.212) 586 0248 Fax: (852) 2802 7638 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.eiu.com Electronic delivery This publication can be viewed by subscribing online at www.store.eiu.com Reports are also available in various other electronic formats, such as CD-ROM, Lotus Notes, online databases and as direct feeds to corporate intranets. For further information, please contact your nearest Economist Intelligence Unit office Copyright © 2004 The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited. -

Nepal Provinces Map Pdf

Nepal provinces map pdf Continue This article is about the provinces of Nepal. For the provinces of different countries, see The Province of Nepal नेपालका देशह Nepal Ka Pradesh haruCategoryFederated StateLocationFederal Democratic Republic of NepalDeitation September 20, 2015MumberNumber7PopulationsMemm: Karnali, 1,570,418Lard: Bagmati, 5,529,452AreasSmallest: Province No. 2, 9,661 square kilometers (3,730 sq m)Largest: Karnali, 27,984 square kilometers (10,805 sq.m.) GovernmentProvincial GovernmentSubdiviions Nepal This article is part of a series of policies and government Non-Trump Fundamental rights and responsibilities President of the Government of LGBT Rights: Bid Gia Devi Bhandari Vice President: Nanda Bahadur Pun Executive: Prime Minister: Hadga Prasad Oli Council of Ministers: Oli II Civil Service Cabinet Secretary Federal Parliament: Speaker of the House of Representatives: Agni Sapkota National Assembly Chair: Ganesh Prasad Timilsin: Judicial Chief Justice of Nepal: Cholenra Shumsher JB Rana Electoral Commission Election Commission : 200820152018 National: 200820132017 Provincial: 2017 Local: 2017 Federalism Administrative Division of the Provincial Government Provincial Assemblies Governors Chief Minister Local Government Areas Municipal Rural Municipalities Minister foreign affairs Minister : Pradeep Kumar Gyawali Diplomatic Mission / Nepal Citizenship Visa Law Requirements Visa Policy Related Topics Democracy Movement Civil War Nepal portal Other countries vte Nepal Province (Nepal: नेपालका देशह; Nepal Pradesh) were formed on September 20, 2015 under Schedule 4 of the Nepal Constitution. Seven provinces were formed by grouping existing districts. The current seven-provincial system had replaced the previous system, in which Nepal was divided into 14 administrative zones, which were grouped into five development regions. Story Home article: Administrative Units Nepal Main article: A list of areas of Nepal Committee was formed to rebuild areas of Nepal on December 23, 1956 and after two weeks the report was submitted to the government. -

Pollution and Pandemic

WITHOUT F EAR OR FAVOUR Nepal’s largest selling English daily Vol XXVIII No. 253 | 8 pages | Rs.5 O O Printed simultaneously in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Bharatpur and Nepalgunj 31.2 C -0.7 C Monday, November 09, 2020 | 24-07-2077 Biratnagar Jumla As winter sets in, Nepal faces double threat: Pollution and pandemic Studies around the world show the risk of Covid-19 fatality is higher with longer exposure to polluted air which engulfs the country as temperatures plummet. ARJUN POUDEL Kathmandu, relative to other cities in KATHMANDU, NOV 8 respective countries. Prolonged exposure to air pollution Last week, a 15-year-old boy from has been linked to an increased risk of Kathmandu, who was suffering from dying from Covid-19, and for the first Covid-19, was rushed to Bir Hospital, time, a study has estimated the pro- after his condition started deteriorat- portion of deaths from the coronavi- ing. The boy, who was in home isola- rus that could be attributed to the tion after being infected, was first exacerbating effects of air pollution in admitted to the intensive care unit all countries around the world. and later placed on ventilator support. The study, published in “When his condition did not Cardiovascular Research, a journal of improve even after a week on a venti- European Society of Cardiology, esti- lator, we performed an influenza test. mated that about 15 percent of deaths The test came out positive,” Dr Ashesh worldwide from Covid-19 could be Dhungana, a pulmonologist, who is attributed to long-term exposure to air also a critical care physician at Bir pollution. -

Rashtriya Prajatantra Party – Recruitment of Children

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: NPL31734 Country: Nepal Date: 14 May 2007 Keywords: Nepal – Chitwan – Maoist insurgency – Peace process – Rashtriya Prajatantra Party – Recruitment of children This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Was Bharatput Chitwan an area affected by the Maoist insurgency, particularly in 2003 and 2004? 2. Has the security situation improved since the peace agreement signed between the government and the Maoists in November 2006 and former Maoist rebels were included in the parliament? 3. Please provide some background information about the Rashtriya Prajatantra Party - its policies, platform, structure, activities, key figures - particularly in the Bharatpur/Chitwan district. 4. Please provide information on the recruitment of children. RESPONSE 1. Was Bharatput Chitwan an area affected by the Maoist insurgency, particularly in 2003 and 2004? The available sources indicate that the municipality of Bharatpur and the surrounding district of Chitwan have been affected by the Maoist insurgency. There have reports of violent incidents in Bharatpur itself, which is the main centre of Chitwan district, but it has reportedly not been as affected as some of the outlying villages of Chitwan. A map of Nepal is attached for the Member’s information which has Bharatpur marked (‘Bharatpur, Nepal’ 1999, Microsoft Encarta – Attachment 1). A 2005 Research Response examined the presence of Maoist insurgents in Chitwan, but does not mention Maoists in Bharatpur. -

Chronology of Major Political Events in Contemporary Nepal

Chronology of major political events in contemporary Nepal 1846–1951 1962 Nepal is ruled by hereditary prime ministers from the Rana clan Mahendra introduces the Partyless Panchayat System under with Shah kings as figureheads. Prime Minister Padma Shamsher a new constitution which places the monarch at the apex of power. promulgates the country’s first constitution, the Government of Nepal The CPN separates into pro-Moscow and pro-Beijing factions, Act, in 1948 but it is never implemented. beginning the pattern of splits and mergers that has continued to the present. 1951 1963 An armed movement led by the Nepali Congress (NC) party, founded in India, ends Rana rule and restores the primacy of the Shah The 1854 Muluki Ain (Law of the Land) is replaced by the new monarchy. King Tribhuvan announces the election to a constituent Muluki Ain. The old Muluki Ain had stratified the society into a rigid assembly and introduces the Interim Government of Nepal Act 1951. caste hierarchy and regulated all social interactions. The most notable feature was in punishment – the lower one’s position in the hierarchy 1951–59 the higher the punishment for the same crime. Governments form and fall as political parties tussle among 1972 themselves and with an increasingly assertive palace. Tribhuvan’s son, Mahendra, ascends to the throne in 1955 and begins Following Mahendra’s death, Birendra becomes king. consolidating power. 1974 1959 A faction of the CPN announces the formation The first parliamentary election is held under the new Constitution of CPN–Fourth Congress. of the Kingdom of Nepal, drafted by the palace. -

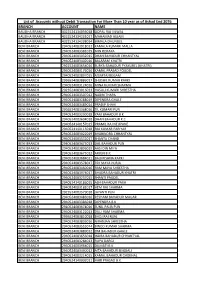

Branch Account Name

List of Accounts without Debit Transaction For More Than 10 year as of Ashad End 2076 BRANCH ACCOUNT NAME BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134056018 GOPAL RAJ SILWAL BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134231017 MAHAMAD ASLAM BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134298014 BIMALA DHUNGEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083918012 KAMALA KUMARI MALLA BENI BRANCH 2940524083381019 MIN ROKAYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083932015 DHAN BAHADUR CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083402016 BALARAM KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2922524083654016 SURYA BAHADUR PYAKUREL (KHATRI) BENI BRANCH 2940524083176016 KAMAL PRASAD POUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083897015 MUMTAJ BEGAM BENI BRANCH 2936524083886017 SHUSHIL KUMAR KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083124016 MINA KUMARI SHARMA BENI BRANCH 2923524083016013 HASULI KUMARI SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083507012 NABIN THAPA BENI BRANCH 2940524083288019 DIPENDRA GHALE BENI BRANCH 2940524083489014 PRADIP SHAHI BENI BRANCH 2936524083368016 TIL KUMARI PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083230018 YAM BAHADUR B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083604018 DHAN BAHADUR K.C BENI BRANCH 2940524140157015 PRAMIL RAJ NEUPANE BENI BRANCH 2940524140115018 RAJ KUMAR PARIYAR BENI BRANCH 2940524083022019 BHABINDRA CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083532017 SHANTA CHAND BENI BRANCH 2940524083475013 DAL BAHADUR PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083896019 AASI DIN MIYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083675012 ARJUN B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083684011 BALKRISHNA KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083578017 TEK MAYA PURJA BENI BRANCH 2940524083460016 RAM MAYA SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083974017 BHADRA BAHADUR KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2940524083237015 SHANTI PAUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524140186015 -

GARP-Nepal National Working Group (NWG)

GARP-Nepal National Working Group (NWG) Dr. Buddha Basnyat, Chair GARP- Nepal, Researcher/Clinician, Oxford University Clinical Research Unit-Nepal\ Patan Academy of Health Sciences Dr. Paras K Pokharel, Vice Chair- GARP Nepal, Professor of Public Health and Community Medicine, BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan Dr. Sameer Mani Dixit, PI GARP- Nepal, Director of Research, Center for Molecular Dynamics, Nepal Dr. Abhilasha Karkey, Medical Microbiologist, Oxford University Clinical Research Unit-Nepal\ Patan Academy of Health Sciences Dr. Bhabana Shrestha, Director, German Nepal Tuberculosis Project Dr. Basudha Khanal, Professor of Microbiology, BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan Dr. Devi Prasai, Member, Nepal Health Economist Association Dr. Mukti Shrestha, Veterinarian, Veterinary Clinics, Pulchowk Dr. Palpasa Kansakar, Microbiologist, World Health Organization Dr. Sharada Thapaliya, Associate Professor, Department of Pharmacology and Surgery, Agriculture and Forestry University–Rampur Mr. Shrawan Kumar Mishra, President, Nepal Health Professional Council Dr. Shrijana Shrestha, Dean, Patan Academy of Health Sciences GARP-Nepal Staff Santoshi Giri, GARP-N Country Coordinator, Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership- Nepal/Nepal Public Health Foundation Namuna Shrestha, Programme Officer, Nepal Public Health Foundation International Advisors Hellen Gelband, Associate Director, Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy Ramanan Laxminarayan, GARP Principal Investigator, Director, Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy Nepal Situation Analysis and Recommendations Preface Nepal Situation Analysis and Recommendations Nepal Situation Analysis and Recommendations Acknowledgement This report on "Situation Analysis and Recommendations: Antibiotic Use and Resistance in Nepal" is developed by Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership (GARP Nepal) under Nepal Public Health Foundation (NPHF). First of all, we are thankful to Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy (CDDEP) for their financial and technical support. -

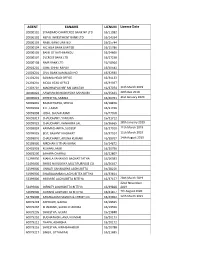

List of Active Agents

AGENT EANAME LICNUM License Date 20000101 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK NP LTD 16/11082 20000102 NEPAL INVESTMENT BANK LTD 16/14334 20000103 NABIL BANK LIMITED 16/15744 20000104 NIC ASIA BANK LIMITED 16/15786 20000105 BANK OF KATHMANDU 16/24666 20000107 EVEREST BANK LTD. 16/27238 20000108 NMB BANK LTD 16/18964 20901201 GIME CHHETRAPATI 16/30543 21001201 CIVIL BANK KAMALADI HO 16/32930 21101201 SANIMA HEAD OFFICE 16/34133 21201201 MEGA HEAD OFFICE 16/34037 21301201 MACHHAPUCHRE BALUWATAR 16/37074 11th March 2019 40000022 AAWHAN BAHUDAYSIYA SAHAKARI 16/35623 20th Dec 2019 40000023 SHRESTHA, SABINA 16/40761 31st January 2020 50099001 BAJRACHARYA, SHOVA 16/18876 50099003 K.C., LAXMI 16/21496 50099008 JOSHI, SHUVALAXMI 16/27058 50099017 CHAUDHARY, YAMUNA 16/31712 50099023 CHAUDHARY, KANHAIYA LAL 16/36665 28th January 2019 50099024 KARMACHARYA, SUDEEP 16/37010 11th March 2019 50099025 BIST, BASANTI KADAYAT 16/37014 11th March 2019 50099026 CHAUDHARY, ARUNA KUMARI 16/38767 14th August 2019 50199000 NIRDHAN UTTHAN BANK 16/14872 50401003 KISHAN LAMKI 16/20796 50601200 SAHARA CHARALI 16/22807 51299000 MAHILA SAHAYOGI BACHAT TATHA 16/26083 51499000 SHREE NAVODAYA MULTIPURPOSE CO 16/26497 51599000 UNNATI SAHAKARYA LAGHUBITTA 16/28216 51999000 SWABALAMBAN LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/33814 52399000 MIRMIRE LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/37157 28th March 2019 22nd November 52499000 INFINITY LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/39828 2019 52699000 GURANS LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/41877 7th August 2020 52799000 KANAKLAXMI SAVING & CREDIT CO. 16/43902 12th March 2021 60079203 ADHIKARI, GAJRAJ -

Youth Experiences of Conflict, Violence and Peacebuilding in Nepal

CASE STUDY ‘Aaba Hamro Paalo’ (It’s Our Time Now): Youth experiences of conflict, violence and peacebuilding in Nepal. Informing the Progress Study on Youth, Peace and Security and the Implementation of Security Council Resolution 2250. SEPTEMBER 30, 2017 Dr. Bhola Prasad Dahal Niresh Chapagain Country Director DMEA Manager Search for Common Ground, Nepal Search for Common Ground, Nepal Phone: +977 9851191666 Phone: +977 9801024762 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Case Study: Youth Consultations on Peace & Security in Nepal Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. 5 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 9 3. Methodology and Description of Research Activities ............................................................................ 10 3.1 Objectives, Population of the Study and Key Research Questions .................................................. -

News Update from Nepal, June 9, 2005

News update from Nepal, June 9, 2005 News Update from Nepal June 9, 2005 The Establishment The establishment in Nepal is trying to consolidate the authority of the state in society through various measures, such as beefing up security measures, extending the control of the administration, dismantling the base of the Maoists and calling the political parties for reconciliation. On May 27 King Gyanendra in his address called on the leaders of the agitating seven-party alliance “to shoulder the responsibility of making all democratic in- stitutions effective through free and fair elections.” He said, “We have consistently held discussions with everyone in the interest of the nation, people and democracy and will continue to do so in the future. We wish to see political parties becoming popular and effective, engaging in the exercise of a mature multiparty democracy, dedicated to the welfare of the nation and people and to peace and good governance, in accordance with people’s aspirations.” Defending the existing Constitution of Nepal 1990 the King argued, “At a time when the nation is grappling with terrorism, the shared commitment and involvement of all political parties sharing faith in democracy is essential to give permanency to the gradually im- proving peace and security situation in the country.” He added, “Necessary preparations have already been initiated to hold these elections, and activate in stages all elected bodies which have suffered a setback during the past three years.” However, King Gy- anendra reiterated that the February I decision was taken to safeguard democracy from terrorism and to ensure that the democratic form of governance, stalled due to growing disturbances, was made effective and meaningful. -

F OCHA Nepal - Fortnightly Situation Overview

F OCHA Nepal - Fortnightly Situation Overview Issue No. 27, covering the period 13 -28 May 2008 Kathmandu, 28 May 2008 Highlights: • Constituent Assembly convenes on 28 May, declares Nepal a democratic republic; king Gyanendra to leave the palace • Food crisis hits remote areas in hills and mountains and fuel shortages adversely affect population • Operational space restricted in some areas by security concerns, including a second attack on an IOM transport • Armed Terai groups increase level of violence, with frequent IEDs, abductions and killings • Negotiations on forming a new government face major hurdles • Bandh in Kathmandu Valley and protests following PLA killing of a Kathmandu businessman • Due to the lack of textbooks and related protests, schools close down for two weeks CONTEXT ceremonial president after the abolition of monarchy, and to amending the interim constitution so that a government can be Political situation formed and removed through a simple majority in the CA. The Terai Madhesh Democratic Party (TMDP) was also expected to Constituent Assembly convenes, republic declared join this agreement. Following a swearing in ceremony of newly elected members On 22 May Senior NC leader and former prime minister Sher on 27 May and under tight security arrangements, and after Bahadur Deuba ruled out his party's involvement in the to-be- more hours of delay, the first session of the Constituent formed government and the possibility of a working alliance Assembly (CA) convened at the Birendra International with Maoists if the latter failed to address the NC‘s seven-point Convention Centre (BICC), Naya Baneshwor, in Kathmandu in demands issued earlier.