Displacement and Development: Long Term Impacts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freedom in West Bengal Revised

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Freedom and its Enemies: Politics of Transition in West Bengal, 1947-1949 * Sekhar Bandyopadhyay Victoria University of Wellington I The fiftieth anniversary of Indian independence became an occasion for the publication of a huge body of literature on post-colonial India. Understandably, the discussion of 1947 in this literature is largely focussed on Partition—its memories and its long-term effects on the nation. 1 Earlier studies on Partition looked at the ‘event’ as a part of the grand narrative of the formation of two nation-states in the subcontinent; but in recent times the historians’ gaze has shifted to what Gyanendra Pandey has described as ‘a history of the lives and experiences of the people who lived through that time’. 2 So far as Bengal is concerned, such experiences have been analysed in two subsets, i.e., the experience of the borderland, and the experience of the refugees. As the surgical knife of Sir Cyril Ratcliffe was hastily and erratically drawn across Bengal, it created an international boundary that was seriously flawed and which brutally disrupted the life and livelihood of hundreds of thousands of Bengalis, many of whom suddenly found themselves living in what they conceived of as ‘enemy’ territory. Even those who ended up on the ‘right’ side of the border, like the Hindus in Murshidabad and Nadia, were apprehensive that they might be sacrificed and exchanged for the Hindus in Khulna who were caught up on the wrong side and vehemently demanded to cross over. -

Any Person May Make a Complaint About The

HIGH COURT OF CHHATTISGARH AT BILASPUR WRIT PETITION (C) No. 4944 of 2009 PETITIONER : Rajendra Singh (Arora). V E R S U S RESPONDENTS : State of Chhattisgarh & Others. PETITION UNDER ARTICLE 226/227 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA SB: Hon’ble Shri Satish K. Agnihotri, J. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Present: Shri Kishore Shrivastava, Senior Advocate with Shri Sanjay Tamrakar, Shri Ashish Shirvastava and Shri Anshuman Shrivastava, Advocates for the petitioner. Shri V.V.S.Moorthy, Deputy Advocate General for the State/ respondent No. 1, 2, 4 and 5. Dr. N.K.Shukla, Senior Advocate with Shri Aditya Khare, Advocates for the respondent No. 7 and 8. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- O R D E R (Delivered on 10th day of July, 2013) 1. The petitioner mainly challenges the order dated 23.07.2007 (Annexure P/14) passed by the High Power State Level Caste Scrutiny Committee i.e. respondent No. 3 (for short ‘the Committee’) wherein the petitioner has been found that he does not belong to “Lohar” i.e. Other Backward Class category, and also the subsequent order dated 28.08.2009 (Annexure P/2) wherein on the basis of the order dated 22.09.2008 (Annexure P/1) the petitioner was disqualified for a further period of five years in view of the provisions of section 19(2) of the Chhattisgarh Municipal Corporation Act, 1956 (for short 'the Act, 1956'). 2. The facts, in brief, are that the petitioner, in the year 2000, contested the election as Councillor from Ward No. 22, Municipal 2 Corporation, Bhilai, declaring himself as a member of “Lohar” community that comes within OBC category on the basis of social status certificate dated 10.04.2000 (Annexure P/3). -

Two Nation Theory: Its Importance and Perspectives by Muslims Leaders

Two Nation Theory: Its Importance and Perspectives by Muslims Leaders Nation The word “NATION” is derived from Latin route “NATUS” of “NATIO” which means “Birth” of “Born”. Therefore, Nation implies homogeneous population of the people who are organized and blood-related. Today the word NATION is used in a wider sense. A Nation is a body of people who see part at least of their identity in terms of a single communal identity with some considerable historical continuity of union, with major elements of common culture, and with a sense of geographical location at least for a good part of those who make up the nation. We can define nation as a people who have some common attributes of race, language, religion or culture and united and organized by the state and by common sentiments and aspiration. A nation becomes so only when it has a spirit or feeling of nationality. A nation is a culturally homogeneous social group, and a politically free unit of the people, fully conscious of its psychic life and expression in a tenacious way. Nationality Mazzini said: “Every people has its special mission and that mission constitutes its nationality”. Nation and Nationality differ in their meaning although they were used interchangeably. A nation is a people having a sense of oneness among them and who are politically independent. In the case of nationality it implies a psychological feeling of unity among a people, but also sense of oneness among them. The sense of unity might be an account, of the people having common history and culture. -

Population Genetics for Autosomal STR Loci in Sikh Population Of

tics: Cu ne rr e en G t y R r e a t s i e d a e r r c e h Dogra, et al., Hereditary Genet 2015, 4:1 H Hereditary Genetics ISSN: 2161-1041 DOI: 10.4172/2161-1041.1000142 Research Article Open Access Population Genetics for Autosomal STR Loci in Sikh Population of Central India Dogra D1, Shrivastava P2*, Chaudhary R3, Gupta U2 and Jain T2 1Department of Biotechnology, Barkatullah University, Bhopal 462023, Madhya Pradesh, India 2DNA Fingerprinting Unit, State Forensic Science Laboratory, Sagar 470001, Madhya Pradesh, India 3Biotechnology Division, Department of Zoology, Government Motilal Vigyan Mahavidyalaya, Bhopal 462023, Madhya Pradesh, India *Corresponding author: Pankaj Shrivastava, DNA Fingerprinting Unit, State Forensic Science Laboratory, Sagar-470001, Madhya Pradesh, India, Tel: 94243 71946, E- mail: [email protected] Rec date: February 4, 2015, Acc date: February 23, 2015, Pub date: February 26, 2015 Copyright: © 2015 Dogra D, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract This study is an attempt to generate genetic database for three endogamous populations of Sikh population (Arora, Jat and Ramgariha) of Central India. The analysis of eight autosomal STR loci (D16S539, D7S820, D13S317, FGA, CSF1PO, D21S11, D18S51, and D2S1338) was done in 140 unrelated Sikh individuals. In all the three studied populations, all loci were in Hardy -Weinberg equilibrium except at locus FGA in Ramgariha Sikh and locus D16S539 in Arora Sikh. -

01720Joya Chatterji the Spoil

This page intentionally left blank The Spoils of Partition The partition of India in 1947 was a seminal event of the twentieth century. Much has been written about the Punjab and the creation of West Pakistan; by contrast, little is known about the partition of Bengal. This remarkable book by an acknowledged expert on the subject assesses partition’s huge social, economic and political consequences. Using previously unexplored sources, the book shows how and why the borders were redrawn, as well as how the creation of new nation states led to unprecedented upheavals, massive shifts in population and wholly unexpected transformations of the political landscape in both Bengal and India. The book also reveals how the spoils of partition, which the Congress in Bengal had expected from the new boundaries, were squan- dered over the twenty years which followed. This is an original and challenging work with findings that change our understanding of parti- tion and its consequences for the history of the sub-continent. JOYA CHATTERJI, until recently Reader in International History at the London School of Economics, is Lecturer in the History of Modern South Asia at Cambridge, Fellow of Trinity College, and Visiting Fellow at the LSE. She is the author of Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition (1994). Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society 15 Editorial board C. A. BAYLY Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine’s College RAJNARAYAN CHANDAVARKAR Late Director of the Centre of South Asian Studies, Reader in the History and Politics of South Asia, and Fellow of Trinity College GORDON JOHNSON President of Wolfson College, and Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society publishes monographs on the history and anthropology of modern India. -

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947. -

Consultancy Services for Urban Planning and Detailed Urban Design for Phase-1 of Ravi Riverfront Urban Development Project

GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB EXPRESSION OF INTEREST CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR URBAN PLANNING AND DETAILED URBAN DESIGN FOR PHASE-1 OF RAVI RIVERFRONT URBAN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Pre-Qualification Documents and Eligibility Criteria for the Selection of International Consulting Firms / Consortium / Joint Venture with Local Firms MAY 2021 RAVI URBAN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER ........................................................................................................................... 4 REQUEST FOR EXPRESSION OF INTEREST DOCUMENT ............................................. 5 NOTICE INVITING REQUEST FOR EXPRESSION INTEREST ......................................... 6 SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 7 i. Project Brief .................................................................................................................... 7 ii. Project Scope .................................................................................................................. 7 iii. Project Area .................................................................................................................... 7 iv. Map of Proposed Boundary of Phase-1 of RRUDP. ...................................................... 8 v. Rationale for the Study ................................................................................................... 9 vi. Tasks .............................................................................................................................. -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

Punjab Public Works Department (B&R)

Punjab Public Works Department (B&R) Establishment Chart ( Dated : 17.09.2021 ) Chief Engineer (Civil) S. Name of Officer/ Email Qualification Present Place of Posting Date of Home Date of No address/ Mobile No. Posting District Birth 1. Er. Arun Kumar M.E. Chief Engineer (North) 12.11.2018 Ludhiana 28.11.1964 [email protected] Incharge of:- [email protected] Construction Circle, Amritsar 9872253744 and Hoshiarpur from 08.03.2019 And Additional Charge Chief Engineer (Headquarter-1), and Chief Engineer (Headquarter-2) and Nodal Officer (Punjab Vidhan Sabha Matters)(Plan Roads) 2. Er. Amardeep Singh Brar, B.E.(Civil) Chief Engineer (West) 03.11.2020 Faridkot 25.03.1965 Chief Engineer, Incharge of: [email protected] Construction Circle Bathinda, and 9915400934 Ferozepur 3. Er.N.R.Goyal, Chief Engineer (South) 03.11.2020 Fazilka 15.05.1964 Chief Engineer Incharge of: [email protected] Construction Circle Patiala - 1 and [email protected] Sangrur, Nodal Officer –Link [email protected] Roads,PMGSY & NABARD 9356717117 Additional Charge Chief Engineer (Quality Assurance) from 19.04.2021 & Chief Vigilance Officer of PWD (B&R) Chief Engineer (NH) from 20.08.2021 Incharge of: National Highway Circle Amritsar, 4. Er.B.S.Tuli, M.E.(Irrigation) ChiefChandigarh, Engineer Fe (Centrozepurral) and Ludhiana 03.11.2020 Ludhiana 15.09.1964 Chief Engineer and Hydraulic Incha rge of: [email protected] Structure) Construction Circle No. 1 & 2 Jalandhar., 9814183304 Construction Circle Pathankot. Nodal Officer (Railways) from 03.11.2020 , Jang-e-Azadi Memorial, Kartarpur and Works under 3054 & 5054 Head 5. -

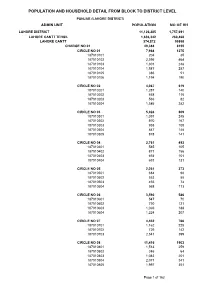

Lahore Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (LAHORE DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH LAHORE DISTRICT 11,126,285 1,757,691 LAHORE CANTT TEHSIL 1,636,342 260,468 LAHORE CANTT 374,872 59858 CHARGE NO 01 49,388 8155 CIRCLE NO 01 7,968 1275 187010101 204 35 187010102 2,596 464 187010103 1,601 248 187010104 1,987 287 187010105 386 51 187010106 1,194 190 CIRCLE NO 02 4,067 619 187010201 1,287 140 187010202 658 115 187010203 536 82 187010204 1,586 282 CIRCLE NO 03 5,024 809 187010301 1,391 245 187010302 970 167 187010303 938 108 187010304 847 148 187010305 878 141 CIRCLE NO 04 2,761 493 187010401 545 105 187010402 871 156 187010403 654 101 187010404 691 131 CIRCLE NO 05 2,261 373 187010501 684 98 187010502 553 88 187010503 456 74 187010504 568 113 CIRCLE NO 06 3,590 586 187010601 547 70 187010602 750 121 187010603 1,069 188 187010604 1,224 207 CIRCLE NO 07 4,432 766 187010701 1,162 225 187010702 729 142 187010703 2,541 399 CIRCLE NO 08 11,416 1903 187010801 1,513 259 187010802 346 64 187010803 1,083 201 187010804 2,071 341 187010805 1,997 351 Page 1 of 162 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (LAHORE DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 187010806 2,952 447 187010807 1,454 240 CIRCLE NO 09 7,869 1331 187010901 1,615 297 187010902 1,604 269 187010903 1,935 316 187010904 1,426 242 187010905 1,289 207 CHARGE NO 02 40,133 6060 CIRCLE NO 01 4,728 834 187020101 969 181 187020102 701 109 187020103 723 124 187020104 409 81 187020105 860 144 187020106 1,066 195 CIRCLE NO 02 13,610 1921 -

The Sikh Dilemma: the Partition of Punjab 1947

The Sikh Dilemma: The Partition of Punjab 1947 Busharat Elahi Jamil Abstract The Partition of India 1947 resulted in the Partition of the Punjab into two, East and West. The 3rd June Plan gave a sense of uneasiness and generated the division of dilemma among the large communities of the British Punjab like Muslims, Hindus and Sikh besetting a holocaust. This situation was beneficial for the British and the Congress. The Sikh community with the support of Congress wanted the proportion of the Punjab according to their own violation by using different modules of deeds. On the other hand, for Muslims the largest populous group of the Punjab, by using the platform of Muslim League showed the resentment because they wanted the decision on the Punjab according to their requirements. Consequently the conflict caused the world’s bloodiest partition and the largest migration of the history. Introduction The Sikhs were the third largest community of the United Punjab before India’s partition. The Sikhs had the historic religious, economic and socio-political roots in the Punjab. Since the annexation of the Punjab, they were faithful with the British rulers and had an influence in the Punjabi society, even enjoying various privileges. But in the 20th century, the Muslims 90 Pakistan Vision Vol. 17 No. 1 Independence Movement in India was not only going to divide the Punjab but also causing the division of the Sikh community between East and West Punjab, which confused the Sikh leadership. So according to the political scenarios in different timings, Sikh leadership changed their demands and started to present different solutions of the Sikh enigma for the geographical transformation of the province.