Port Moresby Urban Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papua New Guinea

PAPUA NEW GUINEA EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS OPERATIONAL LOGISTICS CONTINGENCY PLAN PART 2 –EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITY & OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS SITUATION GLOBAL LOGISTICS CLUSTER – WFP FEBRUARY – MARCH 2011 1 | P a g e A. Summary A. SUMMARY 2 B. EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITIES 4 C. LOGISTICS ACTORS 6 A. THE LOGISTICS COORDINATION GROUP 6 B. PAPUA NEW GUINEAN ACTORS 6 AT NATIONAL LEVEL 6 AT PROVINCIAL LEVEL 9 C. INTERNATIONAL COORDINATION BODIES 10 DMT 10 THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL 10 D. OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURE, SERVICES & STOCKS 11 A. LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURES OF PNG 11 PORTS 11 AIRPORTS 14 ROADS 15 WATERWAYS 17 STORAGE 18 MILLING CAPACITIES 19 B. LOGISTICS SERVICES OF PNG 20 GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS 20 FUEL SUPPLY 20 TRANSPORTERS 21 HEAVY HANDLING AND POWER EQUIPMENT 21 POWER SUPPLY 21 TELECOMS 22 LOCAL SUPPLIES MARKETS 22 C. CUSTOMS CLEARANCE 23 IMPORT CLEARANCE PROCEDURES 23 TAX EXEMPTION PROCESS 24 THE IMPORTING PROCESS FOR EXEMPTIONS 25 D. REGULATORY DEPARTMENTS 26 CASA 26 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 26 NATIONAL INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY AUTHORITY (NICTA) 27 2 | P a g e MARITIME AUTHORITIES 28 1. NATIONAL MARITIME SAFETY AUTHORITY 28 2. TECHNICAL DEPARTMENTS DEPENDING FROM THE NATIONAL PORT CORPORATION LTD 30 E. PNG GLOBAL LOGISTICS CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS 34 A. CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 MAJOR PROBLEMS/BOTTLENECKS IDENTIFIED: 34 SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 B. EXISTING OPERATIONAL CORRIDORS IN PNG 35 MAIN ENTRY POINTS: 35 SECONDARY ENTRY POINTS: 35 EXISTING CORRIDORS: 36 LOGISTICS HUBS: 39 C. STORAGE: 41 CURRENT SITUATION: 41 PROPOSED LONG TERM SOLUTION 41 DURING EMERGENCIES 41 D. DELIVERIES: 41 3 | P a g e B. Existing response capacities Here under is an updated list of the main response capacities currently present in the country. -

RAPID ASSESSMENT of AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS and DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017

RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017 RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY PAPUA NEW GUINEA, 2017 1 Acknowledgements The Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness (RAAB) + Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) was a Brien Holden Vision Institute (the Institute) project, conducted in cooperation with the Institute’s partner in Papua New Guinea (PNG) – PNG Eye Care. We would like to sincerely thank the Fred Hollows Foundation, Australia for providing project funding, PNG Eye Care for managing the field work logistics, Fred Hollows New Zealand for providing expertise to the steering committee, Dr Hans Limburg and Dr Ana Cama for providing the RAAB training. We also wish to acknowledge the National Prevention of Blindness Committee in PNG and the following individuals for their tremendous contributions: Dr Jambi Garap – President of National Prevention of Blindness Committee PNG, Board President of PNG Eye Care Dr Simon Melengas – Chief Ophthalmologist PNG Dr Geoffrey Wabulembo - Paediatric ophthalmologist, University of PNG and CBM Mr Samuel Koim – General Manager, PNG Eye Care Dr Georgia Guldan – Professor of Public Health, Acting Head of Division of Public Health, School of Medical and Health Services, University of PNG Dr Apisai Kerek – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr Robert Ko – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr David Pahau – Ophthalmologist, Boram General Hospital Dr Waimbe Wahamu – Ophthalmologist, Mt Hagen Hospital Ms Theresa Gende -

Financial Inclusion and Financial Capability

Financial Inclusion and Financial Capability in Morobe and Madang Provinces, Papua New Guinea Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized An initial report of the Papua New Guinea Public Disclosure Authorized National Financial Capability Survey Bank of Papua New Guinea Institute of National Affairs 9363_PNG FinancialCapacitySurvey_1601939_CVR.indd 1 11/19/15 8:17 AM Bank of Papua New Guinea Papua New Guinea Institute for National Affairs The World Bank Financial Inclusion and Financial Capability in Morobe and Madang Provinces Papua New Guinea An initial report of the Papua New Guinea National Financial Capability Survey This Project is financially supported by the Korean Poverty Reduction and Socio-Economic Development Trust Fund II 9363_PNG FinancialCapacitySurvey_1601939_CH00_FM.indd 1 11/18/15 10:15 AM Cataloguing-in-Publication Data ISBN 9980-77-182-8 National Library Service—Papua New Guinea First published: June 2015 Published by: Institute of National Affairs P.O. Box 1530 Port Moresby NCD Papua New Guinea Copyright: This report is a joint product of the project team composed of staff and consultants from Bank of Papua New Guinea, the Institute of National Affairs and The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this report are entirely those of the authors and should do not necessarily reflect the views of Board of the Bank of Papua New Guinea, the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent, or the Board of Institute of National Affairs. The Bank of Papua New Guinea, Institute of National Affairs, and The World Bank do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. -

National Capital District

NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT Hospitals • Port Moresby General Hospital Provides antenatal, ART, VCT, Family Planning, Sexual health services. Located in 3 Mile on Taurama Road. Ph: General: 3248200 or Emergency: 3248239 • Paradise Private Hospital Hours: 8:30am - 3pm daily. Fees: Estimated K100 for consultation and after hours K120. Provides antenatal, sexual health education, advice and testing. Located opposite Port Moresby General Hospital on Taurama Rd. Ph: 3256022 • Pacific International Hospital Located on Stores Rd, next to 4 Mile PMV Stop. Ph: 3234400, Mobile: 71114400 or 7111 4011. Police • Police Operations: Ph: 3244331 • Port Moresby Police Station Ph: 321 3468 or 112 FSVU: 77001623 • Six Mile Police Station Ph: 325 1402 Meri Toksave 2014/ 2015 19 • Badili Police station Ph: 321 7945 or FSVU: 321 7088 • Gerehu Police Station Ph: 3260255 • Boroko Police Station Ph Station: 3244312 or 3244273 Family Violence Unit: 3260104 or 3244317 Sexual Offenses Squad: 324 4235 or 324 4257 • Gordons Police Station Ph: 325 1823 • Southern Command HQ Ph: 3212079 Counselling • Stop AIDS Anglicare Stop AIDS PNG offers a range of HIV support services. They offer counselling services to victims of family violence and HIV/AIDS. Located behind the Mobil Service Station, North Waigani. Opening hours: 8am – 4pm. Ph: 325 1855 • Lifeline Lifeline provides religious counselling and have a counselling hotline. Lifeline Port Moresby is located at Section 50, Allotment 4 Mokoraha Rd, North Waigani opposite Bible Translation Association & Fire Station + Adjacent to Koyasi Printing. Ph: 3260011, 3261114 Wireless: 77519657 or 7751 9655. Email: [email protected] Meri Toksave 2014/ 2015 20 • Catholic Family Services CFS offers basic counselling services and family enrichment advice to families with marriage problems and youth with drug and alcohol problems. -

Evaluation of House Rent Prices and Their Affordability in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea

buildings Article Evaluation of House Rent Prices and Their Affordability in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea Eugene E. Ezebilo Property Development Program, National Research Institute, P.O. Box 5854, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea; [email protected] or [email protected] Received: 9 September 2017; Accepted: 1 December 2017; Published: 4 December 2017 Abstract: Access to affordable housing has been a long-standing issue for households in most cities. This paper reports on a study of house rent prices in Port Moresby, factors influencing them, and affordability of the prices. Data was obtained from houses that were advertised for rent in Port Moresby for a period of 13 months and were analysed using the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model. The results show that monthly house rent prices range from 2357 to 34,286 Papua New Guinea Kina (PGK), or 714 to 10,389 U.S. dollars (USD), and the median price was 7286 PGK (2208 USD). Houses located in the central business district had the highest median house rent price, whereas low-income areas had the lowest rent price. By dividing the median house rent price by gross household income, the housing affordability index was 3.4. House rent price was influenced by factors such as number of bedrooms and location. To make house rent prices more affordable for Port Moresby residents, it is necessary to supply more houses for rent relative to demand, especially in low-income areas. Relevant governmental agencies should put more effort toward unlocking more customarily-owned land for housing development and toward facilitating the private sector to construct more low-cost houses for rent, which are affordable for low to middle income households. -

INDEPENDENT STATE of PAPUA NEW GUINEA Company Extract PNG HEALTH ASSURANCE COMPANY LTD 1-118035

INDEPENDENT STATE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA Companies Act 1997 Company Extract As at 15 April 2019 PNG HEALTH ASSURANCE COMPANY LTD 1-118035 General Details Company Type: Local Company Status: Registered Incorporation Date: 10 April 2018 Cessation Date: Annual Return Filing Month: May Own Constitution?: No Previous Names Previous Name Name: HELIOS NO.180 LIMITED From Date: 10 April 2018 To Date: 8 May 2018 Addresses Registered Office Address: Century 21 Building, Ground Floor, Section 35, Allotment 52, Kunai Street, HOHOLA, National Capital District, Papua New Guinea Address for Service: Century 21 Building, Ground Floor, Section 35, Allotment 52, Kunai Street, HOHOLA, National Capital District, Papua New Guinea Postal Address: Po Box 599, KONEDOBU, National Capital District, Papua New Guinea Directors Page 1 of 4 Director Individual Name: Libuse BRIXIOVA Nationality: Czech Republic Residential Address: Stare Misto 52, 506 01 Jicin 1, Czech Republic Postal Address: Stare Misto 52, 506 01 Jicin 1, Czech Republic Appointment Date: 5 February 2019 Director Individual Name: John ELISA Nationality: Papua New Guinea Residential Address: Section 21 Allotment 17 & 18, Pine Street, Hohola, Port Moresby, National Capital District, Papua New Guinea Postal Address: P O Box 421, Port Moresby, National Capital District, Papua New Guinea Appointment Date: 28 November 2018 Director Individual Name: Hoong Chu ENG Nationality: Malaysia Residential Address: Apt Blk 401, Jurong, West Street 42, # 05-541, Singapore, Singapore Postal Address: Apt Blk 401, Jurong, -

Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea ANNUAL REPORT2018 – 2019 ChildFund Papua New Guinea is the representative office of ChildFund Australia – an independent international development organisation that works to reduce poverty for children in developing communities. ChildFund Australia is a member of the ChildFund Alliance – a global network of 11 organisations, which assists more than 13 million children and families in over 60 countries. ChildFund Australia is a registered charity, a member of the Australian Council for International Development, and fully accredited by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade which manages the Australian Government’s overseas aid program. ChildFund began work in Papua New Guinea in 1994, and works in partnership with children, their communities and local organisations and governments to create lasting change, respond to humanitarian emergencies and promote children’s rights. Most projects are implemented in the Central Province and National Capital District with a focus on maternal and child health, nutrition, water and sanitation, education, and child protection and resilience against family and sexual violence. ChildFund PNG also priorities climate change and disaster preparedness. In 2015, ChildFund PNG established the country’s first ever family and sexual violence counselling hotline, which provides nationwide telephone counselling, information and referrals. ChildFund Papua New Guinea Street address: Level 1, Iaraguma Haus, Kawai Drive Hohola, Port Moresby NCD Mailing address: PO Box 671, Gordons NCD Papua New Guinea Phone: +675 323 2544 Email: [email protected] ChildFund Australia Address: Level 8, 162 Goulburn Street, Surry Hills NSW 2010 Phone: 1800 023 600 Email: [email protected] Website: www.childfund.org.au Editor: Nancy Lagdom Photography: ChildFund staff Front cover: Mamopi (centre), age 7, and friends, Papua New Guinea. -

Getting Comfortable: Gender, Class and Belonging in the 'New' Port Moresby

Journal de la Société des Océanistes 144-145 | 2017 Urbanisation en Mélanésie Getting comfortable: gender, class and belonging in the ‘new’ Port Moresby Se mettre à l’aise : genres, classes et appartenance dans le nouveau Port Moresby Ceridwen Spark Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/jso/7772 DOI: 10.4000/jso.7772 ISSN: 1760-7256 Publisher Société des océanistes Printed version Date of publication: 15 December 2017 Number of pages: 147-158 ISSN: 0300-953x Electronic reference Ceridwen Spark, “Getting comfortable: gender, class and belonging in the ‘new’ Port Moresby”, Journal de la Société des Océanistes [Online], 144-145 | 2017, Online since 15 December 2019, connection on 15 March 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/jso/7772 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/jso.7772 Journal de la société des océanistes est mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Getting comfortable: gender, class and belonging in the ‘new’ Port Moresby by Ceridwen Spark* ABSTRACT RÉSUMÉ Port Moresby is consistently represented as a place that is Port-Moresby est régulièrement présentée comme un endroit dangerous for women. While recent transformations in the dangereux pour les femmes. Même si certaines bénéficient plus city have benefited some more than others, developments que d’autres des transformations récentes qui ont eu lieu en ville, in the city are allowing for the creation of new ‘spatial les développements en ville favorisent l’essor de nouveaux espaces texts’ in a place notorious for constraining women. In this urbains dans une ville qui restreint le mouvement des femmes. -

Download Full Sales Listings

18 Mile K3,500,000 Alotau K500,000 Badili K3,000,000 2 1 3 5 2 3 3 2 2 S6408 - Buy away from the city - C21 S7343 - RESIDENCE FOR SALE - SGN S6623 - Perfect Investment Property! - SM Are you trying to buy an investment or residential Just Listed for Sale in Goilanai Estate, Milne Bay Here is a chance for those who are interested in property away from the hustle and bustle of the Province! Double Storey featuring 3 bedroom investing in properties around the Badili area. city? Then this residential investment deal is one residence upstairs and additional 2 bedroom unit Here We have these modern, tri- level and you cannot beat. Situated at 18 mile is this lovely downstairs. Built on reinforced concrete slab and upmarket set of units plus extra land for further property up for sale. Securely fenced in a quiet suspended timber on high steel posts. Has land development coming up on the market. The and peaceful compound; it boasts 4x2 bedrooms area of 0.0450 HA. Fully serviced with water property consists of 2x3 bedrooms with en-suit on and 2x1 bedroom units generating K20, 494.00 reticulation and plumbing services. Ideal for first each master bedrooms asking K2500-K3000/wk per month and 4x3 bedroom houses generating time home buyers or families looking for similar plus another 2x1 bedroom self-contained units K20, 972.00 per month respectively. The property properties, an investor or simply a retirement asking K1000-K1500/wk. The property is fully 18 Mile K6,000,000 Alotau K700,000 Badili 6 3 3 3 1 2 S7337 - Tranquility - AO/MN S6989 - Duplex in Alotau - ES S7103 - Property developers potential Off Sogeri Road, we have this property with a Immediately up for sale is this 2x3 bedroom Here is this perfect opportunity for property land area measuring 4,349 sqm available for duplex with a good yard space. -

Schedule of Ncd School Transport Bus Routes

STUDENTS ONLY BUS ROUTE 01. GORDONS - 9 MILE (BOMANA) STUDENTS ONLY BUS ROUTE 02. 7 MILE - TOWN MORNINGMORNING RUNS RUNS (3 TRIPS) (3 TRIPS) FLEETS - For3 BUSES 1 Bus MORNINGMORNING RUNS RUNS (3 TRIPS) (3 TRIPS) FLEETS - 3For BUSES 1 Bus OPERATING TIME: 6:20 am SCHEDULE- 9:20 am OF NCD SCHOOL TRANSPORTOPERATING TIME: 6:20 amBUS - 9:20 am ROUTES Trip 1 Trip 2 Trip 3 Trip 1 Trip 2 Trip 3 Time: 6:20 am - 7:20 am Time: 7:20 am - 8:20 am Time: 8:20 am - 9:20 am Time: 6:20 am - 7:20 am Time: 7:20 am - 8:20 am Time: 8:20 am - 9:20 am Bus 1. Bus 1. Bus 1. Bus 1. Bus 1. Bus 1. Origin: Gordons Destination: 9 mile Origin: Gordons Destination: 9 mile Origin: Gordons Destination: 9 mile Origin: 7 mile Destination: Town Origin: 7 mile Destination: Town Origin: 7 mile Destination: Town To From To From To From To From To From To From Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Bus Stops Time Gordons 6:20 Bomana 6:47 Gordons 7:20 Bomana 7:45 Gordons 8:20 Bomana 8:45 7 mile 6:20 Town 6:50 7 mile 7:20 Town 7:50 7 mile 8:20 Town 8:50 Erima 6:23 9 mile 7:00 Erima 7:25 9 mile 8:02 Erima 8:25 9 mile 9:02 6 mile 6:24 Koki 6:56 6 mile 7:24 Koki 7:56 6 mile 8:24 Koki 8:56 Wildlife 6:26 8 mile 7:04 Wildlife 7:28 8 mile 8:06 Wildlife 8:28 8 mile 9:06 4 mile 6:34 4 mile 7:06 4 mile 7:34 4 mile 8:06 4 mile 8:34 4 mile 8:06 8 mile 6:29 Wild life 7:10 8 mile 7:31 Wild life 8:11 8 mile 8:31 Wildlife 9:11 Koki 6:44 6 mile 7:15 Koki 7:44 6 mile 8:15 Koki -

Sarawak Companies In

RIMBUNAN HIJAU NAME PRINCIPAL ACTIVITY STATUS REGISTERED ADDRESS DIRECTOR SHAREHOLDER SECRETARY Section 479, Allotment 1, Kennedy Other financial intermediation N.E.C – Allied Investments Limited Registered Road, GORDONS, National Capital James Sze Yuan Lau James Sze Yuan Lau N/A Investment Holdings District, Papua New Guinea Blake Dawson Waldron, 4th Floor, All Round Investments Mogoru Moto Building, Champion Ik King Tiong, Kiew Chiong N/A Removed James Sze Yuan Lau Geok Lian Wong Limited Parade, PORT MORESBY, National Tiong, Thai King Tiong Capital District, Papua New Guinea Section 479, Allotment 1, Kennedy Former director includes Alltime (PNG) Limited Restaurant / Kaibar Operations Registered Road, GORDONS, National Capital Ching Hieng Ho. Current Seng Bok Yap Ching Hieng Ho District, Papua New Guinea director is Seng Bok Yap Section 479, Allotment 1, Kennedy James Sze Yuan Lau, Allure Investments Limited Yet to Commence Registered Road, GORDONS, National Capital James Sze Yuan Lau, Ching Hieng Ho Ching Hieng Ho Ching Hieng Ho District, Papua New Guinea Section 479, Allotment 1, Kennedy Seng Bok Yap, Ngyah Hui Arte Investment Limited Property Investment Registered Road, GORDONS, National Capital Seng Bok Yap, Ngyah Hui Tio N/A Tio District, Papua New Guinea Section 479, Allotment 1, Kennedy Atlantis Investments James Sze Yuan Lau, James Sze Yuan Lau, Ching Hieng Ho, Kaipal Yet to Commence Registered Road, GORDONS, National Capital Ching Hieng Ho Limited Ching Hieng Ho Investments Limited (Registered in PNG) District, Papua New Guinea -

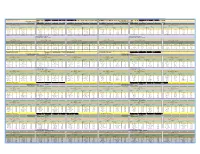

2021 Quarter 1 Payment 1 Batch

2021 QUARTER 1 PAYMENT 1 BATCH 1_Q1P1B121CENPPSV_NCD School CodeSchool Name Sector Code Province Name District Name Account No Bank Name Bb Name Enrollment Balance Pay 69001 BARUNI PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000586837 BSP Port Moresby 429 15,787.20 69002 BAVAROKO PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000489748 BSP Boroko Banking Centr1,957 72,017.60 69003 BOREBOA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000489754 BSP Lae Market Service1,975 C 72,680.00 69004 DIHAROHA/SEVESE MOREA PRIMARY SCHOOLPRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000967421 BSP Port Moresby 1,020 37,536.00 69005 EVEDAHANA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000489766 BSP Boroko Banking Centr1,871 68,852.80 69006 GOLDIE RIVER PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000489757 BSP Boroko Banking Centr642 23,625.60 69007 GEREHU PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000489746 BSP Boroko Banking Centr2,240 82,432.00 69008 HAGARA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000585902 BSP Port Moresby 1,548 56,966.40 69009 HOHOLA DEMONSTRATION PRIMARY SCHOOLPRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000388432 BSP Boroko Banking Centr1,861 68,484.80 69010 EKI VAKI PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICTNATIONAL CAPITAL DISTRICT1000583810 BSP Waigani Banking Cent1,362 50,121.60 69011 JUNE VALLEY PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI NATIONAL