Chapter 1: Battersea High Street Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Network

Milton Keynes, London Birmingham and the North Victoria Watford Junction London Brentford Waterloo Syon Lane Windsor & Shepherd’s Bush Eton Riverside Isleworth Hounslow Kew Bridge Kensington (Olympia) Datchet Heathrow Chiswick Vauxhall Airport Virginia Water Sunnymeads Egham Barnes Bridge Queenstown Wraysbury Road Longcross Sunningdale Whitton TwickenhamSt. MargaretsRichmondNorth Sheen BarnesPutneyWandsworthTown Clapham Junction Staines Ashford Feltham Mortlake Wimbledon Martins Heron Strawberry Earlsfield Ascot Hill Croydon Tramlink Raynes Park Bracknell Winnersh Triangle Wokingham SheppertonUpper HallifordSunbury Kempton HamptonPark Fulwell Teddington Hampton KingstonWick Norbiton New Oxford, Birmingham Winnersh and the North Hampton Court Malden Thames Ditton Berrylands Chertsey Surbiton Malden Motspur Reading to Gatwick Airport Chessington Earley Bagshot Esher TolworthManor Park Hersham Crowthorne Addlestone Walton-on- Bath, Bristol, South Wales Reading Thames North and the West Country Camberley Hinchley Worcester Beckenham Oldfield Park Wood Park Junction South Wales, Keynsham Trowbridge Byfleet & Bradford- Westbury Brookwood Birmingham Bath Spaon-Avon Newbury Sandhurst New Haw Weybridge Stoneleigh and the North Reading West Frimley Elmers End Claygate Farnborough Chessington Ewell West Byfleet South New Bristol Mortimer Blackwater West Woking West East Addington Temple Meads Bramley (Main) Oxshott Croydon Croydon Frome Epsom Taunton, Farnborough North Exeter and the Warminster Worplesdon West Country Bristol Airport Bruton Templecombe -

Buses from Battersea Park

Buses from Battersea Park 452 Kensal Rise Ladbroke Grove Ladbroke Grove Notting Hill Gate High Street Kensington St Charles Square 344 Kensington Gore Marble Arch CITY OF Liverpool Street LADBROKE Royal Albert Hall 137 GROVE N137 LONDON Hyde Park Corner Aldwych Monument Knightsbridge for Covent Garden N44 Whitehall Victoria Street Horse Guards Parade Westminster City Hall Trafalgar Square Route fi nder Sloane Street Pont Street for Charing Cross Southwark Bridge Road Southwark Street 44 Victoria Street Day buses including 24-hour services Westminster Cathedral Sloane Square Victoria Elephant & Castle Bus route Towards Bus stops Lower Sloane Street Buckingham Palace Road Sloane Square Eccleston Bridge Tooting Lambeth Road 44 Victoria Coach Station CHELSEA Imperial War Museum Victoria Lower Sloane Street Royal Hospital Road Ebury Bridge Road Albert Embankment Lambeth Bridge 137 Marble Arch Albert Embankment Chelsea Bridge Road Prince Consort House Lister Hospital Streatham Hill 156 Albert Embankment Vauxhall Cross Vauxhall River Thames 156 Vauxhall Wimbledon Queenstown Road Nine Elms Lane VAUXHALL 24 hour Chelsea Bridge Wandsworth Road 344 service Clapham Junction Nine Elms Lane Liverpool Street CA Q Battersea Power Elm Quay Court R UE R Station (Disused) IA G EN Battersea Park Road E Kensal Rise D ST Cringle Street 452 R I OWN V E Battersea Park Road Wandsworth Road E A Sleaford Street XXX ROAD S T Battersea Gas Works Dogs and Cats Home D A Night buses O H F R T PRINCE O U DRIVE H O WALES A S K V Bus route Towards Bus stops E R E IV A L R Battersea P O D C E E A K G Park T A RIV QUEENST E E I D S R RR S R The yellow tinted area includes every Aldwych A E N44 C T TLOCKI bus stop up to about one-and-a-half F WALE BA miles from Battersea Park. -

223 Streatham Road & 1 Ridge Road, London CR4 2AJ Mixed-Use

Indicative Visualisation 223 Streatham Road & 1 Ridge Road, London CR4 2AJ Mixed-Use Development Opportunity For Sale www.kingsbury-consultants.co.uk 223 Streatham Road & 1 Ridge Road, London CR4 2AJ HOME SUMMARY DESCRIPTION & LOCATION DEVELOPMENT TERMS SUMMARY • Former coachworks plus offices and associated land positioned on a prominent 0.37 acre site • Planning permission for a 4-storey new build scheme comprising 30 residential units totalling 21,044ft2 GIA, all for private sale, and a ground floor A1/B1/D2 commercial unit of 2,099ft2 GIA • Appeal decision pending for a 5-storey scheme comprising 36 residential units plus larger commercial space, with a decision expected in October 2017 • Popular residential location within South West London in close proximity to Tooting Station (direct links to Blackfriars in 24 minutes) • Offers invited in excess of £5,000,000 for the vacant freehold interest, with a £500,000 uplift payable if the Appeal is successful www.kingsbury-consultants.co.uk 223 Streatham Road & 1 Ridge Road, London CR4 2AJ HOME SUMMARY DESCRIPTION & LOCATION DEVELOPMENT TERMS DESCRIPTION The existing property comprises a collection of single-storey light industrial buildings, including ancillary offices, staff areas and storage space, which extend to approximately 2,761ft2 NIA. The site extends to approximately 0.37 acres and benefits from vehicular accesses from both Streatham Road and Ridge Road. The site is bounded by houses to the immediate east (fronting Ridge Road and Caithness Road), with a block of apartments to the west and a parade of shops to the south (both fronting Streatham Road). The property was most recently utilised as a coachworks dealing with the repair and servicing of coaches, buses and cars. -

Buses from St Helier Hospital and Rose Hill

Buses from St. Helier Hospital and Rose Hill 164 280 S1 N44 towards Wimbledon Francis Grove South Merton Mitcham towards Tooting St. George’s Hospital towards Lavender Fields Victoria Road towards Aldwych for Covent Garden from stops RE, RS164, RW FairGreen from280 stops RH, RS, RW fromS1 stops HA, H&R1 fromN44 stops RH, RS, RW towards Wimbledon Francis Grove South Merton Mitcham towards Tooting St. George’s Hospital towards Lavender Fields Victoria Road towards Aldwych for Covent Garden FairGreen from stops RE, RS, RW 164 from stops RH, RS, RW from stops HA, H&R1 from stops RH, RS, RW 154 157 718 164Morden Civic Centre from stops RC, RS, RW from stops HA, RE, RL from stops RH, RJ 154 157 718 Morden Civic Centre 280 S1 N44 Morden Mitcham from stops RC, RS, RW from stops HA, RE, RL from stops RH, RJ Cricket Green 280 S1 N44 Morden(not 164) Mitcham Cricket Green Morden South (notMorden 164) Hall Road MITCHAM Mitcham Junction Morden South Morden 718Hall Road Wandle MITCHAM Mitcham Mitcham Road S1 Junction Mill Green Road 718 Wandle 280 N44 Wilson Hospital 154 Mitcham Road S1 Mill Green Road South Thames College 157 164 Mitcham280 N44 Wilson Hospital 154 Peterborough Road 157 164 section South Thames College Mitcham Middleton Road Hail & Ride Peterborough Road Revesby Road 280 718 N44 S1 Shaftesbury Road section Bishopsford Hail & Ride ★ from stops HA, RC, RL Middleton Road S4 St. Helier Road Robertsbridge Road Green Wrythe LaneRevesby Road Bishopsford 280 718 N44 S1 Shaftesbury Road ★ from stops HASt., HelierRC, RL Avenue Hailsection & Ride Middleton Road Sawtry Close S4 St. -

AMERICAN PALE Bianca Road APA 4.6% (Bermondsey) a Classic Deep

AMERICAN PALE Bianca Road APA 4.6% (Bermondsey) A classic deep amber APA with fruity and refreshing flavours £4.50 Brixton Atlantic APA 5.4% (Brixton) Burst of tropical fruits for a refreshing American pale finish £4.50 INDIAN PALE ALE Mondo Kemosabe IPA 6.4% (Battersea) Dry, malty IPA, a mingle of flavours on the nose classic £4.50 Pressure Drop Mimic 6.2% (Tottenham) A rye IPA, zesty with a subtle spice £4.50 Hackney Push Eject 6.5 (Hackney) Heavily hopped, unfiltered & unfined. Hazy with tropical notes £4.50 SESSION IPA Mondo Little Victories 4.3% (Battersea) A well balanced session IPA, nice body and a hint of sweetness £4.50 LAGER Portobello Pils 4.6% (White City) Full rounded continental flavoured pilsner £3.95 Mondo All Caps 4.9% (Battersea) Corn like sweetness for this American pils £4.50 Brick Peckham Pils 4.8% (Peckham Rye) Czech style pilsner, light & refreshing £4.50 AMBER Gipsy Hill Southpaw 4.2% (Gipsy Hill) Mouthful of malt and hops meet citrus balance £4.50 SOUR Signature Jam Sour 4% (Leyton) A dry hopped raspberry sour, sharp, sweet, topical and zingy £4.50 Weird Beard Sour Slave 4% (Hanwell) Dry hopped kettle sour with a clean citrus acidity (Vg) £4.50 PALE ALE Hackney Kapow! 4.5% (Hackney) Juicy, tropical dry hopped pal. Unfiltered for bigger flavours £4.50 PORTER Bianca Road Vanilla Coffee Porter 4.5% (Bermondsey) Bitter and sweet combine with a hint of vanilla £4.50 BELGIAN & GRISETTE Structure of Matter 4.5% (Ilford) Smooth and quaffable, orangey hops, spicy and malty taste £4.50 Hello, Grisette me you’re looking for? 4.1% (Hanwell) A taste of fresh fruit salad with £4.50 a wheat serenade STOUT £4.50 Brixton Windrush Stout 5% (Brixton) Rich, chocolatey & smooth, with a creamy finish £5.00 Lord Malmölé 7.2% (Battersea) Mondo and Malmo brewery combine for this wonderful stout £4.25 Belleville Southie Stout 5.1% (Wandsworth) Rich and silky with a citrusy-herbal kick. -

Valor Park Croydon

REDHOUSE ROAD I CROYDON I CR0 3AQ VALOR PARK CROYDON AVAILABLE TO LET Q3 2020 DISTRIBUTION WAREHOUSE OPPORTUNITY 5,000 - 85,000 SQ FT (465 - 7,897 SQ M) VALOR PARK CROYDON CR0 3AQ DISTRIBUTION WAREHOUSE OPPORTUNITY Valor Park Croydon is a brand new development of high quality distribution, warehouse units, situated on Redhouse Road, off the A236 leading to the A23 (Purley Way), which is a major trunk road between Central London (11 miles to the north) and the M25 (10 miles to the south). As a major thoroughfare in a densely populated area of South London, Purley Way has been established as a key trade counter and light industrial area as well as a retail warehouse location. HIGH PROFILE LOCAL OCCUPIERS INCLUDE VALOR PARK CROYDON CR0 3AQ SELCO BUILDERS MERCHANT 11 MILES TO CENTRAL LONDON 10 MILES TO M25 J6 VALOR PARK CROYDON MITCHAM ROAD A236 WEST CROYDON THERAPIA IKEA BEDDINGTON CROYDON TOWN LANE LANE STATION CENTRE TRAM STOP TRAM STOP (4MIN WALK) ROYAL MAIL MORGAN STANLEY UPS ZOTEFOAMS VALOR PARK CROYDON CR0 3AQ FIRST CHOICE FOR LAST MILE URBAN Croydon is the UK’s fastest growing economy with 9.3% Annual Gross Value Added. LOGISTICS Average house prices are currently the third most affordable in Outer London and the fourth most affordable in London overall. Valor Park Croydon offers occupiers the opportunity to locate within the most BARNET connected urban centre in the Southeast, WATFORD one of the only London Boroughs linked by multiple modes of public transport; tram, road, M25 bus and rail. A406 J28 Croydon is a major economic centre and a J1 J4 primary retail and leisure destination. -

Air Quality Action Plan for the Royal Borough of Kingston Upon Thames

Air Quality Action Plan For the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames In fulfillment of Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 Local Air Quality Management JULY 2016 SUMMARY This document revises the Council’s current Air Quality Action Plan (AQAP) that was published in 2005 and outlines the actions we will take to prevent deterioration of, and ultimately improve, air quality in the Borough between January 2016 and December 2021. Our medium term plan, ‘Destination Kingston’ sets out our aim of making Kingston fit for modern living - an attractive place to live and work. This plan supports a number of the Destination Kingston 2015-2019 themes and objectives, with clean air and a healthy environment being a fundamental requirement for our communities to live, work and grow. The AQAP also supports a key element of the Our Kingston Programme, established in July 2015 and setting out how the Council will deliver the vision set out in Destination Kingston. Actions to improve Air Quality sit well within Community Outcome 7 established within the programme, which seeks a ‘sustainable borough with a diverse transport network and quality environment for all to enjoy’. Air quality assessments undertaken by the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames identified that the Government's air quality objective for annual mean nitrogen dioxide and daily mean particulates (PM10) were not being met within the Borough (as with most of London) by the target dates. As a consequence, the Council designated an Air Quality Management Area (AQMA) across the whole of the Borough and produced an Air Quality Action Plan in recognition of the legal requirement on the Council to work towards air quality objectives; as required under Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 and the relevant air quality regulations. -

Battersea Reach London SW18 1TA

Battersea Reach London SW18 1TA Rare opportunity to buy or to let commercial UNITS in a thriving SOUTH West London riverside location A prime riverside location situated opposite the River Thames with excellent transport connections. Brand new ground floor units available to let or for sale with Battersea flexible planning uses. Reach London SW18 1TA Units available from 998 sq ft with A1, A3 & E planning uses Local occupiers • Thames-side Battersea location, five minutes from Wandsworth Town station Bathstore • Excellent visibility from York Road which has Mindful Chef c. 75,000 vehicle movements per day Richard Mille • Outstanding river views and and on-site Chelsea Upholstery amenities (including gym, café, gastropub, and Tesco Express) Cycle Republic • Units now available via virtual freehold or to let Fitness Space • Availability from 998 sq ft Randle Siddeley • Available shell & core or Cat A Roche Bobois • Flexible planning uses (A1, A3 & E) • On-site public parking available Tesco Express Yue Float Gourmet Libanais A THRIVING NEW RIVER THAMES NORTH BatterseaA RIVERSIDE DESTINATION ReachB London SW18 1TA PLANNED SCHEME 1,350 RESIDENTIAL UNITS 20a 20b 143 9 3 17 WITH IN EXCESS OF 99% NOW LEGALLY ASCENSIS LOCATION TRAVEL TIMES TOWER COMPLETE OR EXCHANGED Battersea Reach is BALTIMORElocated Richmond COMMODORE14 mins KINGFISHER ENSIGN HOUSE HOUSE HOUSE HOUSE WANDSWORTH BRIDGE near major road links via A3, South Circular (A205) and Waterloo 15 mins 1 First Trade 14 Young’s 23 Wonder Smile A24. KING’S CROSS A10 Bank ST PANCRAS28 mins INTERNATIONAL Waterfront Bar 21a ISLINGTON 2 Cake Boy 24 Ocean Dusk The scheme is five minutesREGENTS EUSTON PARKKing’s Cross 29 mins SHOREDITCH and Restaurant walk from Wandsworth Town15c STATION 8a French Pâtisserie 4 A406 21b 13 10 A1 25 Fonehouse MAIDARailway VALE StationA5 and is a 15b 8b 2 and Coffee Shop 15a Creativemass Heathrow CLERKENWELL31 mins 5 short distance from London15a 8c 18/19 26a PTAH 21c MARYLEBONE A501 4 Gym & Tonic 15b Elliston & NORTH ACTON Heliport. -

Upper Tideway (PDF)

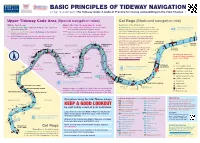

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF TIDEWAY NAVIGATION A chart to accompany The Tideway Code: A Code of Practice for rowing and paddling on the Tidal Thames > Upper Tideway Code Area (Special navigation rules) Col Regs (Starboard navigation rule) With the tidal stream: Against either tidal stream (working the slacks): Regardless of the tidal stream: PEED S Z H O G N ABOVE WANDSWORTH BRIDGE Outbound or Inbound stay as close to the I Outbound on the EBB – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Use the Inshore Zone staying as close to the bank E H H High Speed for CoC vessels only E I G N Starboard (right-hand/bow side) bank as is safe and H (right-hand/bow) side as is safe and inside any navigation buoys O All other vessels 12 knot limit HS Z S P D E Inbound on the FLOOD – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Only cross the river at the designated Crossing Zones out of the Fairway where possible. Go inside/under E piers where water levels allow and it is safe to do so (right-hand/bow) side Or at a Local Crossing if you are returning to a boat In the Fairway, do not stop in a Crossing Zone. Only boats house on the opposite bank to the Inshore Zone All small boats must inform London VTS if they waiting to cross the Fairway should stop near a crossing Chelsea are afloat below Wandsworth Bridge after dark reach CADOGAN (Hammersmith All small boats are advised to inform London PIER Crossings) BATTERSEA DOVE W AY F A I R LTU PIER VTS before navigating below Wandsworth SON ROAD BRIDGE CHELSEA FSC HAMMERSMITH KEW ‘STONE’ AKN Bridge during daylight hours BATTERSEA -

Battersea Area Guide

Battersea Area Guide Living in Battersea and Nine Elms Battersea is in the London Borough of Wandsworth and stands on the south bank of the River Thames, spanning from Fairfield in the west to Queenstown in the east. The area is conveniently located just 3 miles from Charing Cross and easily accessible from most parts of Central London. The skyline is dominated by Battersea Power Station and its four distinctive chimneys, visible from both land and water, making it one of London’s most famous landmarks. Battersea’s most famous attractions have been here for more than a century. The legendary Battersea Dogs and Cats Home still finds new families for abandoned pets, and Battersea Park, which opened in 1858, guarantees a wonderful day out. Today Battersea is a relatively affluent neighbourhood with wine bars and many independent and unique shops - Northcote Road once being voted London’s second favourite shopping street. The SW11 Literary Festival showcases the best of Battersea’s literary talents and the famous New Covent Garden Market keeps many of London’s restaurants supplied with fresh fruit, vegetables and flowers. Nine Elms is Europe’s largest regeneration zone and, according the mayor of London, the ‘most important urban renewal programme’ to date. Three and half times larger than the Canary Wharf finance district, the future of Nine Elms, once a rundown industrial district, is exciting with two new underground stations planned for completion by 2020 linking up with the northern line at Vauxhall and providing excellent transport links to the City, Central London and the West End. -

Upper Mitcham Heritage

had actually started in the 14thC) but increased on an an on increased but 14thC) the in started actually had (which herbs aromatic and medicinal of cultivation the for 18thC the in known best became Mitcham Georgian period Medieval/Tudor villages. surrounding networks(tracks)leadingto centraltoroad then were whicheven (CricketGreen) andLowerGreen Green) (Fair –UpperGreen greens onthecurrent centred Settlements inthelateSaxonandearlyNormanperiods sea-bornefrom raiders. tothecityofLondon theapproaches toprotect area inhabitants mayhavebeenencouragedtosettleinthe the siteofathrivingSaxonsettlement.Itisthought Roman occupationofBritain,andbythe7thC,was the Mitcham wasidentifiedasasettlementlongbefore Roman/Saxon period for horses. coaching parties,withmanyinns stabling facilities fortravellersand Mitcham wasabusythoroughfare and systemhadbeenimproved Londoners. Theroad by Epsom hadbecomeaSpamuchfavoured commons andwatermeadows.Bythemid17thC village withopenfieldsinstripcultivation,extensive agricultural By the17thCMitchamwasaprosperous five separateoccasions. but importantenoughforQueenElizabethItovisiton estates orlandinMitcham–toomanytomentionhere, By theendof16thCmanynotablepeoplehad London. inTudor water–bothscarce airandpure fresh for to LondonandRoyalPalaces,itsreputation Alsoinitsfavourwascloseness good company. forits the 16thCMitchamwasbecomingrenowned attaining thehigherstatusoflandowners.Thusby seekingestatesinMitcham,as ameansof were theCityofLondon andbankersfrom merchants isevidencethatwealthy themid14thCthere From in theConquest. -

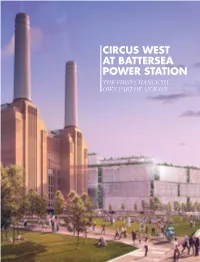

Circus West at Battersea Power Station the First Chance to Own Part of an Icon

CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION THE FIRST CHANCE TO OWN PART OF AN ICON PHASE 1 APARTMENTS 01 02 CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION 03 A GLOBAL ICON 04 AN IDEAL LOCATION 06 A PERFECT POSITION 12 A VISIONARY PLACE 14 SPACES IN WHICH PEOPLE WILL FLOURISH 16 AN EXCITING RANGE OF AMENITIES AND ACTIVITIES 18 CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION 20 RIVER, PARK OR ICON WHAT’S YOUR VIEW? 22 CIRCUS WEST TYPICAL APARTMENT PLANS AND SPECIFICATION 54 THE PLACEMAKERS PHASE 1 APARTMENTS 1 2 CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION A GLOBAL ICON IN CENTRAL LONDON Battersea Power Station is one of the landmarks. Shortly after its completion world’s most famous buildings and is and commissioning it was described by at the heart of Central London’s most the Observer newspaper as ‘One of the visionary and eagerly anticipated fi nest sights in London’. new development. The development that is now underway Built in the 1930s, and designed by one at Battersea Power Station will transform of Britain’s best 20th century architects, this great industrial monument into Battersea Power Station is one of the centrepiece of London’s greatest London’s most loved and recognisable destination development. PHASE 1 APARTMENTS 3 An ideal LOCATION LONDON The Power Station was sited very carefully a ten minute walk. Battersea Park and when it was built. It was needed close to Battersea Station are next door, providing the centre, but had to be right on the river. frequent rail access to Victoria Station. It was to be very accessible, but not part of London’s congestion.