The Robust Beauty of Improper Linear Models in Decision Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

Keane, for Allowing Us to Come and Visit with You Today

BIL KEANE June 28, 1999 Joan Horne and myself, Ann Townsend, interviewers for the Town of Paradise Valley Historical Committee are privileged to interview Bil Keane. Mr. Keane has been a long time resident of the Town of Paradise Valley, but is best known and loved for his cartoon, The Family Circus. Thank you, Mr. Keane, for allowing us to come and visit with you today. May we have your permission to quote you in part or all of our conversation today? Bil Keane: Absolutely, anything you want to quote from it, if it's worthwhile quoting of course, I'm happy to do it. Ann Townsend: Thank you very much. Tell us a little bit about yourself and what brought you to hot Arizona? Bil Keane: Well, it was a TWA plane. I worked on the Philadelphia Bulletin for 15 years after I got out of the army in 1945. It was just before then end of 1958 that I had been bothered each year with allergies. I would sneeze in the summertime and mainly in the spring. Then it got in to be in the fall, then spring, summer and fall. The doctor would always prescribe at that time something that would alleviate it. At the Bulletin I was doing a regular comic and I was editor of their Fun Book. I had a nine to five job there and we lived in Roslyn which was outside Philadelphia and it was one hour and a half commute on the train and subway. I was selling a feature to the newspapers called Channel Chuckles, which was the little cartoon about television which I enjoyed doing. -

Representations of Education in HBO's the Wire, Season 4

Teacher EducationJames Quarterly, Trier Spring 2010 Representations of Education in HBO’s The Wire, Season 4 By James Trier The Wire is a crime drama that aired for five seasons on the Home Box Of- fice (HBO) cable channel from 2002-2008. The entire series is set in Baltimore, Maryland, and as Kinder (2008) points out, “Each season The Wire shifts focus to a different segment of society: the drug wars, the docks, city politics, education, and the media” (p. 52). The series explores, in Lanahan’s (2008) words, an increasingly brutal and coarse society through the prism of Baltimore, whose postindustrial capitalism has decimated the working-class wage and sharply divided the haves and have-nots. The city’s bloated bureaucracies sustain the inequality. The absence of a decent public-school education or meaningful political reform leaves an unskilled underclass trapped between a rampant illegal drug economy and a vicious “war on drugs.” (p. 24) My main purpose in this article is to introduce season four of The Wire—the “education” season—to readers who have either never seen any of the series, or who have seen some of it but James Trier is an not season four. Specifically, I will attempt to show associate professor in the that season four holds great pedagogical potential for School of Education at academics in education.1 First, though, I will present the University of North examples of the critical acclaim that The Wire received Carolina at Chapel throughout its run, and I will introduce the backgrounds Hill, Chapel Hill, North of the creators and main writers of the series, David Carolina. -

The Mockingbird's Nest

The Mockingbird’s Nest A Play in One Act by Craig Bailey Craig Bailey 350 Woodbine Rd Shelburne VT 05482-6777 ©2020 Craig Bailey (802) 655-1197 All rights reserved [email protected] CHARACTERS DAISY In her 80s. ROBYN In her 50s. SETTING/TIME Scene 1 A home. Sometime in the future. Scene 2 The same. Decades later. SYNOPSIS Elderly shut-in DAISY begins to suspect her daughter and live-in caregiver, ROBYN, isn't what she seems to be. 1. SCENE 1 (In the darkness, MUSIC plays. It's a music box-like rendition of "Daisy Bell [Bicycle Built for Two].") (AT RISE: The living room of a modest home. ROBYN sits in an easy chair R. DAISY sits in a wheelchair L.) DAISY (Holding a music box and singing.) Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer do. I'm half crazy, all for the love of you. It won't be a stylish marriage, I can't afford a carriage. But you'll look sweet, Upon the seat, Of a bicycle built for two. ROBYN (Clapping.) Bravo! DAISY The girls would sing it to me incessantly. Every day they would sing it to me. Walking to school. Walking home from school. During recess. Under their breath during class. They thought they were tormenting me, but of course they weren't. As a matter of fact, I liked it! They were meant to be teasing me, but I liked the song! Though I never let those girls know. ROBYN It's a beautiful melody. A beautiful name. DAISY Old fashioned, I'm sure. -

Learn the BEST HOPPER FEATURES

FEATURES GUIDE Learn The 15 BEST HOPPER TIPS YOU’LL FEATURES LOVE! In Just Minutes! Find A Channel Number Fast Watch DISH Anywhere! (And You Don’t Even Have To Be Home) Record Your Entire Primetime Lineup We’ll Show You How Brought to you by 1 YOUR REMOTE CONTENTS 15 TIPS YOU’LL LOVE — Pg. 4 From fi nding a lost remote, binge watching and The Hopper remote control makes it easy for you to watch, search and record more, learn all about Hopper’s best features. programming. Here’s a quick overview of the basics to get you started. Welcome HOME — Pg. 6 You’ve Made A Smart Decision MENU — Pg. 8 With Hopper. Now We’re Here SETTINGS — Pg. 10 DVR TV Power Parental Controls, Guide Settings, Closed Displays your Turns the TV To Make Sure You Understand Captioning, Screen Adjustments, Bluetooth recorded programs. on/off. All That You Can Do With It. and more. Power Guide Turns the receiver Displays the Guide. APPS — Pg. 12 on/off. Netfl ix, Game Finder, Pandora, The Weather CEO and cofounder Charlie Ergen remembers Channel and more. the beginnings of DISH as if it were yesterday. DVR — Pg. 14 The Tennessee native was hauling one of those Operating your DVR, recording series and Home Search enormous C-band TV dish antennas in a pickup managing recordings. Access the Home menu. Searches for programs. truck, along with his fellow cofounders Candy Ergen and Jim DeFranco. It was one of only two PRIMETIME ANYTIME & Apps Info/Help antennas they owned in the early 1980s. -

Pacing in Children's Television Programming

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 364 CS 510 117 AUTHOR McCollum, James F., Jr.; Bryant, Jennings TITLE Pacing in Children's Television Programming. PUB DATE 1999-03-00 NOTE 42p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (82nd, New Orleans, LA, August 4-7, 1999). PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Childrens Television; Content Analysis; Preschool Education; *Programming (Broadcast); Television Research IDENTIFIERS Sesame Street ABSTRACT Following a content analysis, 85 children's programs were assigned a pacing index derived from the following criteria:(1) frequency of camera cuts;(2) frequency of related scene changes;(3) frequency of unrelated scene changes;(4) frequency of auditory changes;(5) percentage of active motion;(6) percentage of active talking; and (7) percentage of active music. Results indicated significant differences in networks' pacing overall and in the individual criteria: the commercial networks present the bulk of the very rapidly paced programming (much of it in the form of cartoons), and those networks devoted primarily to educational programming--PBS and The Learning Channel--present very slow-paced programs. (Contains 26 references, and 12 tables and a figure of data.) (RS) ******************************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * ******************************************************************************** Pacing in Children's Television Programming James F. McCollum Jr. Assistant Professor Department of Communication Lipscomb University Nashville, TN 37204-3951 (615) 279-5788 [email protected] Jennings Bryant Professor Department of Telecommunication and Film Director Institute for Communication Research College of Communication Box 870172 University of Alabama Tuscaloosa, AL 35487-0172 (205) 348-1235 PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND OF EDUCATION [email protected] U.S. -

The Ghosts of War by Ryan Smithson

THE GHOSTS OF WAR BY RYAN SMITHSON RED PHASE I. STUCK IN THE FENCE II. RECEPTION III. BASIC TRAINING PART I IV. MAYBE A RING? V. EQ PLATOON VI. GI JOE SCHMO VII. COLD LIGHTNING VIII. THE EIGHT HOUR DELAY IX. THE TOWN THAT ACHMED BUILT X. A TASTE OF DEATH WHITE PHASE XI. BASIC TRAINING PART II XII. RELIEF XIII. WAR MIRACLES XIV. A TASTE OF HOME XV. SATAN’S CLOTHES DRYER XVI. HARD CANVAS XVII. PETS XVIII. BAZOONA CAT XIX. TEARS BLUE PHASE XX. BASIC TRAINING PART III XXI. BEST DAY SO FAR XXII. IRONY XXIII. THE END XXIV. SILENCE AND SILHOUETTES XXV. WORDS ON PAPER XXVI. THE INNOCENT XXVII. THE GHOSTS OF WAR Ghosts of War/R. Smithson/2 PART I RED PHASE I. STUCK IN THE FENCE East Greenbush, NY is a suburb of Albany. Middle class and about as average as it gets. The work was steady, the incomes were suitable, and the kids at Columbia High School were wannabes. They wanted to be rich. They wanted to be hot. They wanted to be tough. They wanted to be too cool for the kids who wanted to be rich, hot, and tough. Picture me, the average teenage boy. Blond hair and blue eyes, smaller than average build, and, I’ll admit, a little dorky. I sat in third period lunch with friends wearing my brand new Aeropostale t-shirt abd backwards hat, wanting to be self-confident. The smell of greasy school lunches filled e air. We were at one of the identical, fold out tables. -

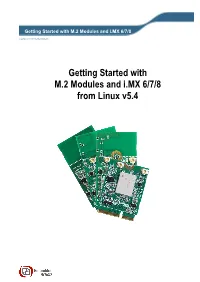

Wireless Communication

Getting Started with M.2 Modules and i.MX 6/7/8 Copyright 2020 © Embedded Artists AB Getting Started with M.2 Modules and i.MX 6/7/8 from Linux v5.4 Getting Started with M.2 Modules and i.MX 6/7/8 from Linux v5.4 Page 2 Embedded Artists AB Jörgen Ankersgatan 12 SE-211 45 Malmö Sweden http://www.EmbeddedArtists.com Copyright 2020 © Embedded Artists AB. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any language or computer language, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, magnetic, optical, chemical, manual or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Embedded Artists AB. Disclaimer Embedded Artists AB makes no representation or warranties with respect to the contents hereof and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular purpose. Information in this publication is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of Embedded Artists AB. Feedback We appreciate any feedback you may have for improvements on this document. Send your comments by using the contact form: www.embeddedartists.com/contact. Trademarks All brand and product names mentioned herein are trademarks, services marks, registered trademarks, or registered service marks of their respective owners and should be treated as such. Copyright 2020 © Embedded Artists AB Rev A Getting Started with M.2 Modules and i.MX 6/7/8 from Linux v5.4 Page 3 Table of Contents 1 Document Revision History ................................. 5 2 Introduction .......................................................... -

Transcript of Interview with Rube Goldberg

Transcript of interview with Rube Goldberg Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface Oral History Interview with Rube Goldberg 1970 New York City Interviewer: Emily Nathan The original format for this document is Microsoft Word 10.1. Some formatting has been changed for web presentation. Speakers are indicated by their initials. Interview EN: Emily Nathan RG: Rube Goldberg EN: Mr. Goldberg, I understand the exhibition of your work in Washington is going to go way back into your past. It'll really be an enormous retrospective. RG: Yes. I'm very pleased. I think it's going to be one of the best things that's . gonna . to be sort of the climax of my career. I don't want to say that it's like looking at your own obituary [Laughs], you know, when, when they glorify somebody . EN: Looking at your own life, I would say. RG: Yeah, when they glorify somebody later in life, or they generally do it after he's gone, but I'm still here and I guess I'll be here after November the 24th when the show opens . [Laughs] EN: [Laughs] I'm sure you will. RG: . and, uh, I'm very pleased, because they, uh, they're doing it so thoroughly; they have so many, you know. They think of so many that things I've forgotten; they have drawings that I've forgotten. They have illustrations . EN: How did they find the ones you had forgotten? RG: Well, I don't know. -

Nickelodeon Sets All That Premiere Date--Saturday, June 15, at 8:30 P.M

Vital Information! Nickelodeon Sets All That Premiere Date--Saturday, June 15, at 8:30 P.M. (ET/PT), Featuring Performance by Grammy® Nominated Multiplatinum Powerhouse Trio Jonas Brothers! May 14, 2019 Original Cast Members Kel Mitchell, Lori Beth Denberg and Josh Server Guest Star in Weekly Sketch Comedy Series Return Share it: @Nickelodeon @allthat (Instagram) #allthat Click HEREfor Photo and HERE for Video BURBANK, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--May 14, 2019-- Nickelodeon’s brand-new version of its legendary sketch comedy series, All That, returns on Saturday, June 15, at 8:30 p.m. (ET/PT), with an all new cast and performance by Grammy® nominated multiplatinum powerhouse Jonas Brothers. The premiere also features appearances from legacy cast members Kel Mitchell, Lori Beth Denberg and Josh Server, who helped make the original series a 90s icon for an entire generation of kids. Executive produced by original cast member Kenan Thompson, All That will air weekly on Saturdays at 8:30 p.m. (ET/PT) on Nickelodeon. As the countdown to the premiere begins, the show opens with Mitchell, Denberg and Server imparting advice and words of wisdom to the new cast of All That sharpens their comedic skills. Coming this season, classic roles are reprised in some of the series’ most memorable sketches including: Mitchell as fast-food slacker “Ed” in “Good Burger”, Denberg dropping some hilarious new advice in “Vital Information” and appearing as “Ms. Hushbaum,” the hypocritical “Loud Librarian”. The new cast and additional guest stars will be announced at a later date. The Jonas Brothers will close the show with a performance of their smash hit “Sucker,” which debuted at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 and the US Hot Digital Songs chart. -

How Gaming Helps Shape LEGO® Star Wars™ Holiday Special

How Gaming Helps Shape LEGO® Star Wars™ Holiday Special The LEGO® Star Wars™ Holiday Special was — in some ways — shaped by the upcoming game LEGO Star Wars: The Skywalker Saga and other LEGO video game elements, the movie’s director said in a recent episode of podcast Bits N’ Bricks. Director Ken Cunningham mentioned the upcoming game while discussing how the movie, which hit Disney+ in November, came about. “I was working on the Jurassic series at the time and had a meeting actually with my head of production, and he said that we were being looked at to do some Star Wars content,” he said. “They wanted to really see if we could hit that sort of cinematic Star Wars look. And so, we dug in on that. I looked really strongly at the films and actually, at the time, the trailer for the new game that's coming out in the new year. “We looked at the quality of that, which was really awesome. And we just sort of pushed as hard as we could, delivered a look I was pretty satisfied with, and apparently, so was Lucasfilm because we got the gig.” A team of more than 100 at Atomic Cartoons worked on the film, which Cunningham described as a “rip-roaring time romp through all the Star Wars fan-favorite moments.” Cunningham also noted that while the now infamous 1978 Star Wars holiday special was a “touchstone” for this film, it wasn’t meant to be a starting point. What that means is that while you’ll find plenty of references — like Life Day and Chewbacca dad Itchy — you won’t find any of the sometimes-artless musical numbers. -

Body, Mind, and How to Figure All That

Body, mind, and how to figure all that out Rafael Núñez Associate Professor, Department of Cognitive Science, University of California, San Diego, USA “The body influences the way we think”; “The mind is embodied”; “Thoughts that we can produce ultimately have their foundation in our embodiment”. For many years I have been working – as a cognitive scientist interested in abstraction and conceptual systems – with such views of thought and mind. I have been involved in many projects investigating children’s thinking, abstract concepts in indigenous people from West Africa and the Andes, and mathematicians teaching and solving problems. So far, what I have seen and read seems to support the view that thought and mind are indeed very much embodied. The statements above, however, are not quotes from the usual literature I encountered in psychology, linguistics, or neuroscience. Rather, they are from documents produced at a lab that for two decades has been investigating robots! That’s right, Rolf Pfeifer’s AI Lab at the University of Zurich. It was more than a decade ago or so, that I started to learn about the views on embodiment at the AI Lab in Zurich. By then I had finished my graduate work in Switzerland and I was heading to Berkeley and Stanford for post-doc appointments where I would be learning about fascinating new foundations for the study of mind and body, of cognition and flesh, behavior and matter. I was especially interested in understanding the nature of human abstraction, in comprehending how we systematize knowledge of domains that transcend immediate sensory experience.