What Is Face Anyway? Jiying Song George Fox University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clara Wing-Chung Ho FUSHI

Clara Wing-chung Ho FUSHI: THE SECOND SEX AND THE THIRD SEX IN TRADITIONAL CHINA* A Double Meaning of Fushi If we borrow the Western concept to describe women as the second sex in Chinese history,1 then eunuchs could certainly be understood as the third sex.2 The third sex was an artificial one. It was the first sex, male, aiming to ensure the chastity of the second sex, who created a third sex. In imperial families, castration of male attendants made it possible to prevent palace * The author gratefully acknowledges Professor Kwai-cheung Lo, who read the first draft of this article and offered many valuable comments. An earlier version of this article was presented at the workshop “The Future of Chinese Gender Studies in Europe, Asia and the United States” held in Luxembourg, June 24-26, 2005. The author also acknowledges all the constructive comments and suggestions given by the workshop participants, Professors Harriet Zurndorfer and Angela Ki Che Leung in particular. The author is also grateful to Professor Paolo Santan- gelo and Dr. Donatella Guida for their editorial assistance. The shortcomings of the final ver- sion are, of course, the author’s own. 1 Simone de Beauvior’s (1908-1986) Le Deuxième Sexe (The Second Sex) was first published in French in 1949. Employing biological, psychological and historical analysis, it explains how the men-women relation was compared to the master-slave relation. The book was soon trans- lated into many languages and became a major and well-known reference on gender studies in the second half of the 20th century. -

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation A/L Krishnan Thiinash Bachelor of Information Technology March 2015 A/L Selvaraju Theeban Raju Bachelor of Commerce January 2015 A/P Balan Durgarani Bachelor of Commerce with Distinction March 2015 A/P Rajaram Koushalya Priya Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Hiba Mohsin Mohammed Master of Health Leadership and Aal-Yaseen Hussein Management July 2015 Aamer Muhammad Master of Quality Management September 2015 Abbas Hanaa Safy Seyam Master of Business Administration with Distinction March 2015 Abbasi Muhammad Hamza Master of International Business March 2015 Abdallah AlMustafa Hussein Saad Elsayed Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Abdallah Asma Samir Lutfi Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdallah Moh'd Jawdat Abdel Rahman Master of International Business July 2015 AbdelAaty Mosa Amany Abdelkader Saad Master of Media and Communications with Distinction March 2015 Abdel-Karim Mervat Graduate Diploma in TESOL July 2015 Abdelmalik Mark Maher Abdelmesseh Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Master of Strategic Human Resource Abdelrahman Abdo Mohammed Talat Abdelziz Management September 2015 Graduate Certificate in Health and Abdel-Sayed Mario Physical Education July 2015 Sherif Ahmed Fathy AbdRabou Abdelmohsen Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdul Hakeem Siti Fatimah Binte Bachelor of Science January 2015 Abdul Haq Shaddad Yousef Ibrahim Master of Strategic Marketing March 2015 Abdul Rahman Al Jabier Bachelor of Engineering Honours Class II, Division 1 -

Chinese Zheng and Identity Politics in Taiwan A

CHINESE ZHENG AND IDENTITY POLITICS IN TAIWAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MUSIC DECEMBER 2018 By Yi-Chieh Lai Dissertation Committee: Frederick Lau, Chairperson Byong Won Lee R. Anderson Sutton Chet-Yeng Loong Cathryn H. Clayton Acknowledgement The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the support of many individuals. First of all, I would like to express my deep gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Frederick Lau, for his professional guidelines and mentoring that helped build up my academic skills. I am also indebted to my committee, Dr. Byong Won Lee, Dr. Anderson Sutton, Dr. Chet- Yeng Loong, and Dr. Cathryn Clayton. Thank you for your patience and providing valuable advice. I am also grateful to Emeritus Professor Barbara Smith and Dr. Fred Blake for their intellectual comments and support of my doctoral studies. I would like to thank all of my interviewees from my fieldwork, in particular my zheng teachers—Prof. Wang Ruei-yu, Prof. Chang Li-chiung, Prof. Chen I-yu, Prof. Rao Ningxin, and Prof. Zhou Wang—and Prof. Sun Wenyan, Prof. Fan Wei-tsu, Prof. Li Meng, and Prof. Rao Shuhang. Thank you for your trust and sharing your insights with me. My doctoral study and fieldwork could not have been completed without financial support from several institutions. I would like to first thank the Studying Abroad Scholarship of the Ministry of Education, Taiwan and the East-West Center Graduate Degree Fellowship funded by Gary Lin. -

Ideophones in Middle Chinese

KU LEUVEN FACULTY OF ARTS BLIJDE INKOMSTSTRAAT 21 BOX 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË ! Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas'Van'Hoey' ' Presented(in(fulfilment(of(the(requirements(for(the(degree(of(( Master(of(Arts(in(Linguistics( ( Supervisor:(prof.(dr.(Jean=Christophe(Verstraete((promotor)( ( ( Academic(year(2014=2015 149(431(characters Abstract (English) Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas Van Hoey This M.A. thesis investigates ideophones in Tang dynasty (618-907 AD) Middle Chinese (Sinitic, Sino- Tibetan) from a typological perspective. Ideophones are defined as a set of words that are phonologically and morphologically marked and depict some form of sensory image (Dingemanse 2011b). Middle Chinese has a large body of ideophones, whose domains range from the depiction of sound, movement, visual and other external senses to the depiction of internal senses (cf. Dingemanse 2012a). There is some work on modern variants of Sinitic languages (cf. Mok 2001; Bodomo 2006; de Sousa 2008; de Sousa 2011; Meng 2012; Wu 2014), but so far, there is no encompassing study of ideophones of a stage in the historical development of Sinitic languages. The purpose of this study is to develop a descriptive model for ideophones in Middle Chinese, which is compatible with what we know about them cross-linguistically. The main research question of this study is “what are the phonological, morphological, semantic and syntactic features of ideophones in Middle Chinese?” This question is studied in terms of three parameters, viz. the parameters of form, of meaning and of use. -

Strain-Induced Self Organization of Metal−Insulator

NANO LETTERS 2006 Strain-Induced Self Organization of Vol. 6, No. 10 Metal−Insulator Domains in 2313-2317 Single-Crystalline VO2 Nanobeams Junqiao Wu,†,‡ Qian Gu,†,‡ Beth S. Guiton,‡ Nathalie P. de Leon,‡ Lian Ouyang,‡ and Hongkun Park*,‡,§ Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology and Department of Physics, HarVard UniVersity, 12 Oxford Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Received August 5, 2006; Revised Manuscript Received September 14, 2006 ABSTRACT We investigated the effect of substrate-induced strain on the metal−insulator transition (MIT) in single-crystalline VO2 nanobeams. A simple nanobeam−substrate adhesion leads to uniaxial strain along the nanobeam length because of the nanobeam’s unique morphology. The strain changes the relative stability of the metal (M) and insulator (I) phases and leads to spontaneous formation of periodic, alternating M−I domain patterns during the MIT. The spatial periodicity of the M−I domains can be modified by changing the nanobeam thickness and the Young’s modulus of the substrate. Many unique properties of transition metal oxides, including scanned probe investigations reveal that a simple adhesive ferroelectricity,1,2 colossal magnetoresistivity,3-5 and high- interaction between the nanobeam and the substrate leads to 6 TC superconductivity, originate from the interplay between a coherent uniaxial strain on the nanobeam. The resulting structural phase transitions and nanoscale electronic and strain causes spontaneous formation of alternating nanoscale magnetic ordering. Lattice strain, which affects the relative metal (M)-insulator (I) domains along the nanobeam length stability of competing structural phases, thus has a profound and thus produces nanoscale M-I heterostructures within a influence on the electrical, optical, and magnetic properties compositionally homogeneous material.24 The present study 1-6 of these oxides. -

Pdf More Experiment Studies Showing Anti-SARS-Cov-2 Activity of TCM Or Its Components Will Be Published Acknowledgement in the Near Future

Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, Vol. 16 1708 Ivyspring International Publisher International Journal of Biological Sciences 2020; 16(10): 1708-1717. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45538 Review Traditional Chinese Medicine in the Treatment of Patients Infected with 2019-New Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): A Review and Perspective Yang Yang*, Md Sahidul Islam*, Jin Wang, Yuan Li and Xin Chen State Key Laboratory of Quality Research in Chinese Medicine, Institute of Chinese Medical Sciences, University of Macau, Macau SAR 999078, China *These authors have contributed equally to this work. Corresponding author: Prof. Xin Chen, Institute of Chinese Medical Sciences, University of Macau, Avenida da Universidade, Taipa, Macau SAR 999078, China. Tel.: (853) 8822 4513; Fax: (853) 2884 1358. E-mail address: [email protected]; ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2628-4027 © The author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). See http://ivyspring.com/terms for full terms and conditions. Received: 2020.03.02; Accepted: 2020.03.08; Published: 2020.03.15 Abstract Currently, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2, formerly known as 2019-nCoV, the causative pathogen of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)) has rapidly spread across China and around the world, causing an outbreak of acute infectious pneumonia. No specific anti-virus drugs or vaccines are available for the treatment of this sudden and lethal disease. The supportive care and non-specific treatment to ameliorate the symptoms of the patient are the only options currently. At the top of these conventional therapies, greater than 85% of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients in China are receiving Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) treatment. -

Surname First Name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen

2018 DRIVERS' CATEGORISATION LIST Updated on 09/07/2018 Drivers in red : revised categorisation Drivers in blue : new categorisation Surname First name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen Klaus Bronze Abbott Hunter Silver Abbott James Silver Abe Kenji Bronze Abelli Julien Silver Abergel Gabriele Bronze Abkhazava Shota Bronze Abra Richard Silver Abreu Attila Gold Abril Vincent Gold Abt Christian Silver Abt Daniel Gold Accary Thomas Silver Acosta Hinojosa Julio Sebastian Silver Adam Jonathan Platinum Adams Rudi Bronze Adorf Dirk Silver Aeberhard Juerg Silver Afanasiev Sergei Silver Agostini Riccardo Gold Aguas Rui Gold Ahlin-Kottulinsky Mikaela Silver Ahrabian Darius Bronze Ajlani Karim Bronze Akata Emin Bronze Aksenov Stanislas Silver Al Faisal Abdulaziz Silver Al Harthy Ahmad Silver Al Masaood Humaid Bronze Al Qubaisi Khaled Bronze Al-Azhari Karim Bronze Alberico Neil Silver Albers Christijan Platinum Albert Michael Silver Albuquerque Filipe Platinum Alder Brian Silver Aleshin Mikhail Platinum Alesi Giuliano Silver Alessi Diego Silver Alexander Iradj Silver Alfaisal Saud Bronze Alguersuari Jaime Platinum Allegretta Vincent Silver Alleman Cyndie Silver Allemann Daniel Bronze Allen James Silver Allgàuer Egon Bronze Allison Austin Bronze Allmendinger AJ Gold Allos Manhal Bronze Almehairi Saeed Silver Almond Michael Silver Almudhaf Khaled Bronze Alon Robert Silver Alonso Fernando Platinum Altenburg Jeff Bronze Altevogt Peter Bronze Al-Thani Abdulrahman Silver Altoè Giacomo Silver Aluko Kolawole Bronze Alvarez Juan Cruz Silver Alzen -

Chun Ning “Jeanie”

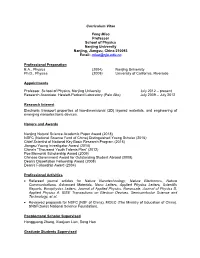

Curriculum Vitae Feng Miao Professor School of Physics Nanjing University Nanjing, Jiangsu, China 210093 Email: [email protected] Professional Preparation B.A., Physics (2004) Nanjing University Ph.D., Physics (2009) University of California, Riverside Appointments Professor, School of Physics, Nanjing University July 2012 – present Research Associate, Hewlett-Packard Laboratory (Palo Alto) July 2009 – July 2012 Research Interest Electronic transport properties of two-dimensional (2D) layered materials, and engineering of emerging nanoelectronic devices. Honors and Awards Nanjing Natural Science Academic Paper Award (2018) NSFC (National Science Fund of China) Distinguished Young Scholar (2016) Chief Scientist of National Key Basic Research Program (2015) Jiangsu Young Investigator Award (2014) China’s “Thousand Youth Talents Plan” (2012) Poe Memorial Scholarship Award (2009) Chinese Government Award for Outstanding Student Abroad (2009) Dean's Dissertation Fellowship Award (2008) Dean’s Fellowship Award (2004) Professional Activities Refereed journal articles for Nature Nanotechnology, Nature Electronics, Nature Communications, Advanced Materials, Nano Letters, Applied Physics Letters, Scientific Reports, Europhysics Letters, Journal of Applied Physics, Nanoscale, Journal of Physics D, Applied Physics A, IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices, Semiconductor Science and Technology, et al. Reviewed proposals for NSFC (NSF of China), MOEC (The Ministry of Education of China), SNSF(Swiss National Science Foundation). Postdoctoral Scholar Supervised Hongguang Zhang, Xiaojuan Lian, Song Hao Graduate Students Supervised Erfu Liu, Yajun Fu, Kang Xu, Junwen Zeng, Mingsheng Long, Lili Zhang, Miao Wang, Yaojia Wang, Yu Wang, Chenyu Wang, Chen Pan, Anyuan Gao, Qiao Li, Zecheng Ma, Xiaowei Liu, Chenchen Wu, Tianjun Cao, Shengnan Yan, Cong Wang Publications (Total citations: 11378 by Feb. 2018) 1. -

Names of Chinese People in Singapore

101 Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 7.1 (2011): 101-133 DOI: 10.2478/v10016-011-0005-6 Lee Cher Leng Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore ETHNOGRAPHY OF SINGAPORE CHINESE NAMES: RACE, RELIGION, AND REPRESENTATION Abstract Singapore Chinese is part of the Chinese Diaspora.This research shows how Singapore Chinese names reflect the Chinese naming tradition of surnames and generation names, as well as Straits Chinese influence. The names also reflect the beliefs and religion of Singapore Chinese. More significantly, a change of identity and representation is reflected in the names of earlier settlers and Singapore Chinese today. This paper aims to show the general naming traditions of Chinese in Singapore as well as a change in ideology and trends due to globalization. Keywords Singapore, Chinese, names, identity, beliefs, globalization. 1. Introduction When parents choose a name for a child, the name necessarily reflects their thoughts and aspirations with regards to the child. These thoughts and aspirations are shaped by the historical, social, cultural or spiritual setting of the time and place they are living in whether or not they are aware of them. Thus, the study of names is an important window through which one could view how these parents prefer their children to be perceived by society at large, according to the identities, roles, values, hierarchies or expectations constructed within a social space. Goodenough explains this culturally driven context of names and naming practices: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore The Shaw Foundation Building, Block AS7, Level 5 5 Arts Link, Singapore 117570 e-mail: [email protected] 102 Lee Cher Leng Ethnography of Singapore Chinese Names: Race, Religion, and Representation Different naming and address customs necessarily select different things about the self for communication and consequent emphasis. -

The Dark Warrior Guide to Chinese Medicine

The Dark Warrior Guide to Chinese Medicine 玄武中医指南 Volume II Basic Concepts of Pathology John E. Pirog 1 The Dark Warrior Guide to Chinese Medicine Volume II Basic Concepts of Pathology © John Pirog 2016 2 Preface to Volume II This second volume of Dark Warrior continues where the first left off. Having learned how the body behaves when it functions normally, we will now explore what happens when it is ill. You will soon find that the arrangement of subject matter in this volume is quite different from that of standard Chinese medical texts. Decades of teaching experience has shown me that Chinese medicine is easier to learn if it is sequenced as it is here. You will get the most out of Dark Warrior, therefore, if you read it like a novel, from start to finish, without skipping chapters or jumping ahead. Each new idea is explained when it is first introduced, and later chapters build on ideas previously covered. But while my pedagogy is designed for Western learning styles, I have taken pains to ensure that the ideas in Dark Warrior are representative of Chinese medicine as it is taught in China. I have used the vocabulary developed by Wiseman and his collaborators to establish a clear pedigree between translated technical terms and their Chinese- language originals. To make translatability even clearer, I have included the character whenever an important technical term is introduced. In a very few instances I have changed the Wiseman translation; these exceptions can be found in the appendix in the back of the book. -

Data Mining: an Introduction 1 Ishwar K

TABLE OF CONTENTS v Copyrighted Material Dan Braha (Ed), Data Mining for Design and Manufacturing, Springer, 2002, 544 p., Hardcover, ISBN: 1-4020-0034-0 PREFACE Data Mining for Design and Manufacturing ix Dan Braha PART I: OVERVIEW OF DATA MINING 1 Data Mining: An Introduction 1 Ishwar K. Sethi 2 A Survey of Methodologies and Techniques for Data 41 Mining and Intelligent Data Discovery Ricardo Gonzalez and Ali Kamrani PART II: DATA MINING IN PRODUCT DESIGN 3 Data Mining in Scientific Data 61 Stephan Rudolph and Peter Hertkorn 4 Learning to Set Up Numerical Optimizations of 87 Engineering Designs Mark Schwabacher, Thomas Ellman, and Haym Hirsh 5 Automatic Classification and Creation of 127 Classification Systems Using Methodologies of "Knowledge Discovery in Databases (KDD)" Hans Grabowski, Ralf-Stefan Lossack, and Jörg Weißkopf 6 Data Mining for Knowledge Acquisition in 145 Engineering Design Yoko Ishino and Yan Jin 7 A Data Mining-Based Engineering Design Support 161 System: A Research Agenda Carol J Romanowski and Rakesh Nagi vi DATA MINING FOR DESIGN AND MANUFACTURING PART III: DATA MINING IN MANUFACTURING 8 Data Mining for High Quality and Quick Response 179 Manufacturing Jang-Hee Lee and Sang-Chan Park 9 Data Mining for Process and Quality Control in the 207 Semiconductor Industry Mark Last and Abraham Kandel 10 Analyzing Maintenance Data Using Data Mining 235 Methods Carol J Romanowski and Rakesh Nagi 11 Methodology of Mining Massive Data Sets for 255 Improving Manufacturing Quality/Efficiency Jye-Chyi (JC) Lu 12 Intelligent Process Control System for Quality 289 Improvement by Data Mining in the Process Industry Sewon Oh, Jooyung Han, and Hyunbo Cho 13 Data Mining by Attribute Decomposition with 311 Semiconductor Manufacturing Case Study Oded Maimon and Lior S. -

Inhabiting Literary Beijing on the Eve of the Manchu Conquest

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CITY ON EDGE: INHABITING LITERARY BEIJING ON THE EVE OF THE MANCHU CONQUEST A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY NAIXI FENG CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................................v ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................. viii 1 A SKETCH OF THE NORTHERN CAPITAL...................................................................1 1.1 The Book ........................................................................................................................4 1.2 The Methodology .........................................................................................................25 1.3 The Structure ................................................................................................................36 2 THE HAUNTED FRONTIER: COMMEMORATING DEATH IN THE ACCOUNTS OF THE STRANGE .................39 2.1 The Nunnery in Honor of the ImperiaL Sister ..............................................................41 2.2 Ant Mounds, a Speaking SkulL, and the Southern ImperiaL Park ................................50