The Identity Crisis of Being John Malkovich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18 Jan 19 28 Feb 19

18 JAN 19 28 FEB 19 1 | 18 JAN 19 - 28 FEB 19 49 BELMONT STREET | BELMONTFILMHOUSE.COM What does it mean, ‘to play against type’? Come January/February you may find many examples. Usually it’s motivated by the opportunity to hold aloft a small gold-plated statue, but there are plenty memorable occasions where Hollywood’s elite pulled this trope off fantastically. Think Charlize Theron in Monster. Maybe Jim Carrey in Eternal Sunshine? Or Heath Ledger as Joker. These performances often come to dominate award season. Directors wrenching a truly transformative rendition out of their leads can be the difference between a potential big winner fading into obscurity, or being written into history. The class of 2019 appears particularly full of these turns. There might well be as much intrigue in figuring out which will be remembered, as in watching the performances themselves. ‘Unrecognisable as’ awards could go out to Margot Robbie as Elizabeth I in Mary Queen Of Scots; Melissa McCarthy in Can You Ever Forgive Me?; Nicole Kidman in Destroyer; Christian Bale as Dick Cheney in Vice. Others of course have been down this road before. Steve Carell has come a long, long way since Michael Scott and he looks tremendous in Beautiful Boy. And Matt Dillon, who we’ll see in The House That Jack Built, has always had a penchant for the slightly off-colour. There’s probably no one more off-colour than Lars von Trier. Screening for one night only. At Belmont Filmhouse we try to play against type as much as possible. -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

Embargoed Until 12:00PM ET / 9:00AM PT on Tuesday, April 23Rd, 2019

Embargoed Until 12:00PM ET / 9:00AM PT on Tuesday, April 23rd, 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 24th ANNUAL NANTUCKET FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES FEATURE FILM LINEUP DANNY BOYLE’S YESTERDAY TO OPEN FESTIVAL ALEX HOLMES’ MAIDEN TO CLOSE FESTIVAL LULU WANG’S THE FAREWELL TO SCREEN AS CENTERPIECE DISNEY•PIXAR’S TOY STORY 4 PRESENTED AS OPENING FAMILY FILM IMAGES AVAILABLE HERE New York, NY (April 23, 2019) – The Nantucket Film Festival (NFF) proudly announced its feature film lineup today. The opening night selection for its 2019 festival is Universal Pictures’ YESTERDAY, a Working Title production written by Oscar nominee Richard Curtis (Four Weddings and a Funeral, Love Actually, and Notting Hill) from a story by Jack Barth and Richard Curtis, and directed by Academy Award® winner Danny Boyle (Slumdog Millionaire, Trainspotting, 28 Days Later). The film tells the story of Jack Malik (Himesh Patel), a struggling singer-songwriter in a tiny English seaside town who wakes up after a freak accident to discover that The Beatles have never existed, and only he remembers their songs. Sony Pictures Classics’ MAIDEN, directed by Alex Holmes, will close the festival. This immersive documentary recounts the thrilling story of Tracy Edwards, a 24-year-old charter boat cook who became the skipper of the first ever all-female crew to enter the Whitbread Round the World Yacht Race. The 24th Nantucket Film Festival runs June 19-24, 2019, and celebrates the art of screenwriting and storytelling in cinema. A24’s THE FAREWELL, written and directed by Lulu Wang, will screen as the festival’s Centerpiece film. -

CANDY L. WALKEN Hair Design/Stylist IATSE 706

CANDY L. WALKEN Hair Design/Stylist IATSE 706 FILM UNTITLED DAVID CHASE PROJECT Department Head, Los Angeles Aka TWYLIGHT ZONES Director: David Chase THE BACK-UP PLAN Department Head Director: Alan Poul Cast: Alex O’Loughlin, Melissa McCarthy, Michaela Watkins NAILED Department Head Director: David O. Russell Cast: Jessica Biel, Jake Gyllenhaal, Catherine Keener, James Marsden THE MAIDEN HEIST Department Head Director: Peter Hewitt Cast: Christopher Walken, Marcia Gay Harden, William H. Macy THE HOUSE BUNNY Hair Designer/Department Head Personal Hair Stylist to Anna Faris Director: Fred Wolf Cast: Emma Stone, Kat Dennings, Katharine McPhee, Rumer Willis DISTURBIA Department Head Director: D.J. Caruso Cast: Shia LaBeouf, Carrie-Anne Moss, David Morse, Aaron Yoo FREEDOM WRITERS Department Head Director: Richard La Gravenese Cast: Imelda Staunton, Scott Glenn, Robert Wisdom MUST LOVE DOGS Personal Hair Stylist to Diane Lane Director: Gary David Goldberg A LOT LIKE LOVE Department Head Director: Nigel Cole Cast: Ashton Kutcher, Amanda Peet CELLULAR Personal Hair Stylist to Kim Basinger Director: David R. Ellis ELVIS HAS LEFT THE BUILDING Personal Hair Stylist to Kim Basinger Director: Joel Zwick UNDER THE TUSCAN SUN Personal Hair Stylist to Diane Lane Director: Audrey Wells THE MILTON AGENCY Candy L. Walken 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Hair Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 3 SUSPECT ZERO Department Head Director: Elias Merhige Cast: Aaron -

The Honorable Mentions Movies – LIST 3

The Honorable mentions Movies – LIST 3: 1. Modern Times by Charles Chaplin (1936) 2. Pinocchio by Hamilton Luske et al. (1940) 3. Late Spring by Yasujirō Ozu (1949) 4. The Virgin Spring by Ingmar Bergman (1960) 5. Charade by Stanley Donen (1963) 6. The Soft Skin by François Truffaut (1964) 7. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? by Mike Nichols (1966) 8. Dog Day Afternoon by Sidney Lumet (1975) 9. Love Unto Death by Alain Resnais (1984) 10. Kiki's Delivery Service by Hayao Miyazaki (1989) 11. Bram Stoker's Dracula by Francis Ford Coppola (1992) 12. Léon: The Professional by Luc Besson (1994) 13. Princess Mononoke by Hayao Miyazaki (1997) 14. Fight Club by David Fincher (1999) 15. Rosetta by Jean-Pierre Dardenne, Luc Dardenne (1999) 16. The Ninth Gate by Roman Polanski (1999) 17. O Brother, Where Art Thou? by Ethan Coen, Joel Coen (2000) 18. The Return Andrey Zvyagintsev (2003) 19. The Sea Inside by Alejandro Amenábar (2004) 20. Broken Flowers by Jim Jarmusch (2005) 21. Climates by Nuri Bilge Ceylan (2006) 22. The Prestige by Christopher Nolan (2006) 23. The Class by Laurent Cantet (2008) 24. Mother by Bong Joon-ho (2009) 25. Shutter Island by Martin Scorsese (2010) 26. The Tree of Life by Terrence Malick (2011) 27. The Artist by Michel Hazanavicius (2011) 28. Melancholia by Lars von Trier (2011) 29. Hugo by Martin Scorsese (2011) 30. Twice Born by Sergio Castellitto (2012) 31. August Osage county by John Wells (2013) 32. 12 Years a Slave by Steve McQueen (2013) 33. The Best Offer by Giuseppe Tornatore (2013) 34. -

Actores Transnacionales: Un Estudio En Cinema Internacional

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects Hispanic Studies 2016 Actores transnacionales: un estudio en cinema internacional Lydia Hartlaub Illinois Wesleyan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/hispstu_honproj Part of the Spanish Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hartlaub, Lydia, "Actores transnacionales: un estudio en cinema internacional" (2016). Honors Projects. 11. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/hispstu_honproj/11 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty in the Hispanic Studies department at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Hartlaub 1 Actores transnacionales: un estudio en cinema internacional Lydia Hartlaub con Prof. Carmela Ferradáns Hartlaub 2 Tabla de contenidos Introducción…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Cine de España…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 Pedro Almodóvar…………………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

JERI BAKER Hair Stylist IATSE 706

JERI BAKER Hair Stylist IATSE 706 FILM FATALE Personal Hair Stylist to Hillary Swank Director: Deon Taylor ANT-MAN AND THE WASP Department Head Director: Peyton Reed Cast: Hannah John-Karmen, Paul Rudd, Judy Greer DEN OF THEIVES Department Head; Personal Hair Stylist to Gerard Butler Director: Christian Gudegast Cast: Gerard Butler, Dawn Olivieri SUBURBICON Personal Hair Stylist to Julianne Moore Director: George Clooney SPIDER-MAN: HOMECOMING Department Head Director: Jon Watts Cast: Tom Holland, Michael Keaton, Marisa Tomei, Gwyneth Paltrow, Jon Favreau, Laura Harrier, Tyne Daley KEEP WATCHING Department Head Director: Sean Carter Cast: Bella Thorne GHOST IN THE SHELL Personal Hair Stylist to Scarlett Johansson Director: Rupert Saunders CAPTAIN AMERICA: CIVIL WAR Personal Hair Stylist to Scarlett Johansson Directors: Anthony Russo, Joe Russo CAPTAIN AMERICA: THE WINTER Personal Hair Stylist to Scarlett Johansson SOLDIER Directors: Anthony Russo, Joe Russo CHEF Personal Hair Stylist to Scarlett Johansson Director: Jon Favreau WISH I WAS HERE Department Head Director: Zach Braff Cast: Zach Braff, Kate Hudson, Ashley Greene, Josh Gad, Mandy Patinkin, Joey King DON JON Personal Hair Stylist to Scarlett Johansson Director: Joseph Gordon-Levitt THE MILTON AGENCY Jeri Baker 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Hair Stylist Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 4 WE BOUGHT A ZOO Assistant Department Head Director: Cameron Crowe Cast: Thomas Haden Church, Elle Fanning BUTTER Assistant Department Head Director: Jim Field Smith Cast: Hugh Jackman, Alicia Silverstone, Ty Burrell SUPER 8 Assistant Department Head Director: J.J. Abrams Cast: Kyle Chandler, Jessica Tuck PEEP WORLD Department Head Director: Barry W. -

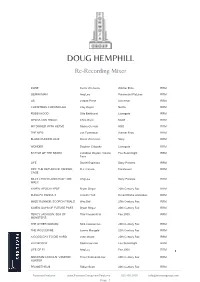

DOUG HEMPHILL Re-Recording Mixer

DOUG HEMPHILL Re-Recording Mixer DUNE Denis Villeneuve Warner Bros. RRM GEMINI MAN Ang Lee Paramount Pictures RRM US Jordan Peele Universal RRM CHRISTMAS CHRONICLES Clay Kaytis Netflix RRM ROBIN HOOD Otto Bathhurst Lionsgate RRM OPERATION FINALE Chris Weitz MGM RRM MY DINNER WITH HERVÉ Sacha Gervasi HBO RRM THE MEG Jon Turteltaub Warner Bros. RRM BLADE RUNNER 2049 Denis Villeneuve Sony RRM WONDER Stephen Chbosky Lionsgate RRM BATTLE OF THE SEXES Jonathan Dayton, Valerie Fox Searchlight RRM Faris LIFE Daniel Espinosa Sony Pictures RRM XXX: THE RETURN OF XANDER D.J. Caruso Paramount RRM CAGE BILLY LYNN’S LONG HALFTIME Ang Lee Sony Pictures RRM WALK X-MEN: APOCALYPSE Bryan Singer 20th Century Fox RRM KUNG FU PANDA 3 Jennifer Yuh DreamWorks Animation RRM MAZE RUNNER: SCORCH TRIALS Wes Ball 20th Century Fox RRM X-MEN: DAYS OF FUTURE PAST Bryan Singer 20th Century Fox RRM PERCY JACKSON: SEA OF Thor Freudenthal Fox 2000 RRM MONSTERS THE OTHER WOMAN Nick Cassavetes 20th Century Fox RRM THE WOLVERINE James Mangold 20th Century Fox RRM A GOOD DAY TO DIE HARD John Moore 20th Century Fox RRM HITCHCOCK Sacha Gervasi Fox Searchlight RRM LIFE OF PI Ang Lee Fox 2000 RRM ABRAHAM LINCOLN: VAMPIRE Timur Bekmambetov 20th Century Fox RRM HUNTER PROMETHEUS Ridley Scott 20th Century Fox RRM Formosa Features www.FormosaGroup.com/Features 323.850.2800 [email protected] Page 1 THE CABIN IN THE WOODS Drew Goddard Lionsgate RRM THIS MEANS WAR McG 20th Century Fox RRM WE BOUGHT A ZOO Cameron Crowe 20th Century Fox RRM PEARL JAM TWENTY Cameron Crowe Tremolo Productions RRM RISE OF THE PLANETS OF THE Rupert Wyatt 20th Century Fox RRM APES CRAZY STUPID LOVE Glenn Ficarra, John Requa Warner Bros RRM MR. -

3. Groundhog Day (1993) 4. Airplane! (1980) 5. Tootsie

1. ANNIE HALL (1977) 11. THIS IS SPINAL Tap (1984) Written by Woody Allen and Marshall Brickman Written by Christopher Guest & Michael McKean & Rob Reiner & Harry Shearer 2. SOME LIKE IT HOT (1959) Screenplay by Billy Wilder & I.A.L. Diamond, Based on the 12. THE PRODUCERS (1967) German film Fanfare of Love by Robert Thoeren and M. Logan Written by Mel Brooks 3. GROUNDHOG DaY (1993) 13. THE BIG LEBOWSKI (1998) Screenplay by Danny Rubin and Harold Ramis, Written by Ethan Coen & Joel Coen Story by Danny Rubin 14. GHOSTBUSTERS (1984) 4. AIRplaNE! (1980) Written by Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis Written by James Abrahams & David Zucker & Jerry Zucker 15. WHEN HARRY MET SALLY... (1989) 5. TOOTSIE (1982) Written by Nora Ephron Screenplay by Larry Gelbart and Murray Schisgal, Story by Don McGuire and Larry Gelbart 16. BRIDESMAIDS (2011) Written by Annie Mumolo & Kristen Wiig 6. YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN (1974) Screenplay by Gene Wilder and Mel Brooks, Screen Story by 17. DUCK SOUP (1933) Gene Wilder and Mel Brooks, Based on Characters in the Novel Story by Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby, Additional Dialogue by Frankenstein by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley Arthur Sheekman and Nat Perrin 7. DR. STRANGELOVE OR: HOW I LEARNED TO STOP 18. There’s SOMETHING ABOUT MARY (1998) WORRYING AND LOVE THE BOMB (1964) Screenplay by John J. Strauss & Ed Decter and Peter Farrelly & Screenplay by Stanley Kubrick and Peter George and Bobby Farrelly, Story by Ed Decter & John J. Strauss Terry Southern 19. THE JERK (1979) 8. BlaZING SADDLES (1974) Screenplay by Steve Martin, Carl Gottlieb, Michael Elias, Screenplay by Mel Brooks, Norman Steinberg Story by Steve Martin & Carl Gottlieb Andrew Bergman, Richard Pryor, Alan Uger, Story by Andrew Bergman 20. -

The Mind-Game Film Thomas Elsaesser

9781405168625_4_001.qxd 8/10/08 11:58 AM Page 13 1 The Mind-Game Film Thomas Elsaesser Playing Games In December 2006, Lars von Trier’s The Boss of It All was released. The film is a comedy about the head of an IT company hiring a failed actor to play the “boss of it all,” in order to cover up a sell-out. Von Trier announced that there were a number of (“five to seven”) out-of-place objects scattered throughout, called Lookeys: “For the casual observer, [they are] just a glitch or a mistake. For the initiated, [they are] a riddle to be solved. All Lookeys can be decoded by a system that is unique. [. .] It’s a basic mind game, played with movies” (in Brown 2006). Von Trier went on to offer a prize to the first spectator to spot all the Lookeys and uncover the rules by which they were generated. “Mind-game, played with movies” fits quite well a group of films I found myself increasingly intrigued by, not only because of their often weird details and the fact that they are brain-teasers as well as fun to watch, but also because they seemed to cross the usual boundaries of mainstream Hollywood, independent, auteur film and international art cinema. I also realized I was not alone: while the films I have in mind generally attract minority audiences, their appeal manifests itself as a “cult” following. Spectators can get passionately involved in the worlds that the films cre- ate – they study the characters’ inner lives and back-stories and become experts in the minutiae of a scene, or adept at explaining the improbabil- ity of an event. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

Film: the Case of Being John Malkovich Martin Barker, University of Aberystwyth, UK

The Pleasures of Watching an "Off-beat" Film: the Case of Being John Malkovich Martin Barker, University of Aberystwyth, UK It's a real thinking film. And you sort of ponder on a lot of things, you think ooh I wonder if that is possible, and what would you do -- 'cos it starts off as such a peculiar film with that 7½th floor and you think this is going to be really funny all the way through and it's not, it's extremely dark. And an awful lot of undercurrents to it, and quite sinister and … it's actually quite depressing if you stop and think about it. [Emma, Interview 15] M: Last question of all. Try to put into words the kind of pleasure the film gave you overall, both at the time you were watching and now when you sit and think about it. J: Erm. I felt free somehow and very "oof"! [sound of sharp intake of breath] and um, it felt like you know those wheels, you know in a funfair, something like that when I left, very "woah-oah" [wobbling and physical instability]. [Javita, Interview 9] Hollywood in the 1990s was a complicated place, and source of films. As well as the tent- pole summer and Christmas blockbusters, and the array of genre or mixed-genre films, through its finance houses and distribution channels also came an important sequence of "independent" films -- films often characterised by twisted narratives of various kinds. Building in different ways on the achievements of Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Pulp Fiction (1994), all the following (although not all might count as "independents") were significant success stories: The Usual Suspects (1995), The Sixth Sense (1999), American Beauty (1999), Magnolia (1999), The Blair Witch Project (1999), Memento (2000), Vanilla Sky (2001), Adaptation (2002), and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004).