Theodore Wores Papers, 1880-1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Fernald Caroline Dissert

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE VISUALIZATION OF THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST: ETHNOGRAPHY, TOURISM, AND AMERICAN INDIAN SOUVENIR ARTS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By CAROLINE JEAN FERNALD Norman, Oklahoma 2017 THE VISUALIZATION OF THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST: ETHNOGRAPHY, TOURISM, AND AMERICAN INDIAN SOUVENIR ARTS A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS BY ______________________________ Dr. W. Jackson Rushing, III, Chair ______________________________ Mr. B. Byron Price ______________________________ Dr. Alison Fields ______________________________ Dr. Kenneth Haltman ______________________________ Dr. David Wrobel © Copyright by CAROLINE JEAN FERNALD 2017 All Rights Reserved. For James Hagerty Acknowledgements I wish to extend my most sincere appreciation to my dissertation committee. Your influence on my work is, perhaps, apparent, but I am truly grateful for the guidance you have provided over the years. Your patience and support while I balanced the weight of a museum career and the completion of my dissertation meant the world! I would certainly be remiss to not thank the staff, trustees, and volunteers at the Millicent Rogers Museum for bearing with me while I finalized my degree. Your kind words, enthusiasm, and encouragement were greatly appreciated. I know I looked dreadfully tired in the weeks prior to the completion of my dissertation and I thank you for not mentioning it. The Couse Foundation, the University of Oklahoma’s Charles M. Russell Center, and the School of Visual Arts, likewise, deserve a heartfelt thank you for introducing me to the wonderful world of Taos and supporting my research. A very special thank you is needed for Ginnie and Ernie Leavitt, Carl Jones, and Byron Price. -

The Elegant Home

THE ELEGANT HOME Select Furniture, Silver, Decorative and Fine Arts Monday November 13, 2017 Tuesday November 14, 2017 Los Angeles THE ELEGANT HOME Select Furniture, Silver, Decorative and Fine Arts Monday November 13, 2017 at 10am Tuesday November 14, 2017 at 10am Los Angeles BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES Automated Results Service 7601 W. Sunset Boulevard +1 (323) 850 7500 European Furniture and +1 (800) 223 2854 Los Angeles, California 90046 +1 (323) 850 6090 fax Decorative Arts bonhams.com Andrew Jones ILLUSTRATIONS To bid via the internet please visit +1 (323) 436 5432 Front cover: Lot 215 (detail) PREVIEW www.bonhams.com/24071 [email protected] Day 1 session page: Friday, November 10 12-5pm Lot 733 (detail) Saturday, November 11 12-5pm Please note that telephone bids American Furniture and Day 2 session page: Sunday, November 12 12-5pm must be submitted no later Decorative Arts Lot 186 (detail) than 4pm on the day prior to Brooke Sivo Back cover: Lot 310 (detail) SALE NUMBER: 24071 the auction. New bidders must +1 (323) 436 5420 Lots 1 - 899 also provide proof of identity [email protected] and address when submitting CATALOG: $35 bids. Telephone bidding is only Decorative Arts and Ceramics available for lots with a low Jennifer Kurtz estimate in excess of $1000. +1 (323) 436 5478 [email protected] Please contact client services with any bidding inquiries. Silver and Objects of Vertu Aileen Ward Please see pages 321 to 323 +1 (323) 436 5463 for bidder information including [email protected] Conditions of Sale, after-sale collection, and shipment. -

The Broken Wheel and the Taos Society of Artists (Ernest L

The Broken Wheel and the Taos Society of Artists (Ernest L. Blumenschein Home & Museum Brochure 2016) American artist Joseph Henry Sharp briefly visited Taos in 1893. While studying painting in Paris two years later, he met and became friends with two other young American art students, Ernest L. Blumenschein and Bert G.Phillips. Sharp told them about the Indian village of Taos and the spectacular land. Blumenschein later wrote “I remember being impressed as I pigeon-holed that curious name in my memory with hope that some day I might pass that way.” On his return from Paris in 1896, Blumenschein was commissioned by McClures Magazine to do a series of illustrations in Arizona and New Mexico. He was so taken by the Southwest that he convinced his friend Bert Phillips to join him two years later on a sketching trip from Denver to Mexico. Having spent the summer of 1898 painting and camping in the Rocky Mountains, the two young artists started painting their way south in the early fall. On September 3, while driving the storm- ravaged roads of northern New Mexico, the wheel on their light surrey slipped onto a deep rut and broke. The men tossed a three-dollar gold piece to determine who would carry the wheel to the nearest blacksmith for repair. Blumenschein lost the toss and so made the twenty-mile trek to Taos with the broken wheel. Thus began a great experiment in American Art. Blumenschein (called “Blumy” by his many friends) stayed in Taos only a few months and then returned to New York. -

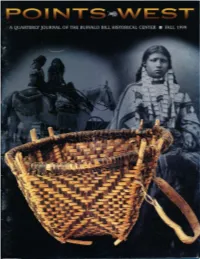

Points-West 1999.09.Pdf

-.- A NOTE FROM THE DIRECTOR Tn the previous (Summer, 1999) issue of 3 I PLAINS INDIAN MUSEUM : d RE/NTERPR ETATION LPoints West. a paragraph was inadvertently 4 omitted from the article by Gordon A NATTJRAL HISTORY MUSEUM:A RAIiONAIC ANd 7 Status of a Natural History Museumfor the BufJaIo Wickstrom titled, There's Never Been an Actor B|II Historical Center Like Buffalo BiII. Here is the author's closing SEASONS OF DISCOVERY: A HANdS-ON CENtET paragraph stating his thesis in its entirety: 9 for Children and Families 10 HARRY JACRSON CELEBRATED "This season ol 1876-77 epitomizes the t2 ABOT]T CROW INDIAN HORSES career of this unique actor-and the burden of this essay-who for a sustained stage CFM ACQUIRES GATLING GUN MOUNT l4 career played only himsell in dramas exclu- TWO NEW EXHIBITS ADDED TO CFM 15 sively about himself based more or less on t6 IN SI GHTS-P EG COE HON O RED materials of historical and cultural import that THE ROYAL ARMOURIES: Bulfalo BiIl Exhibit he was instrumental in generating on the Travels to Leeds, England. t7 scene of the national westward expansion." 19 TNTRIDUCING'RENDEZVIUS RIYALE" FRzM rHE HoRSE's MourH 22 Readers' Forum We want to know what you think about what we're doing. Please send your Letters to the Editor to: Editor: Points West Readers' POINIS WEST is published quarterly as a benelit of membership in the Buffalo Bill Historical center. For membership information contact: Forum. Bullalo Bill Historical Center, 720 Jane Sanders Director of Membership Sheridan Avenue, Cody, WY 82414. -

READ ME FIRST Here Are Some Tips on How to Best Navigate, find and Read the Articles You Want in This Issue

READ ME FIRST Here are some tips on how to best navigate, find and read the articles you want in this issue. Down the side of your screen you will see thumbnails of all the pages in this issue. Click on any of the pages and you’ll see a full-size enlargement of the double page spread. Contents Page The Table of Contents has the links to the opening pages of all the articles in this issue. Click on any of the articles listed on the Contents Page and it will take you directly to the opening spread of that article. Click on the ‘down’ arrow on the bottom right of your screen to see all the following spreads. You can return to the Contents Page by clicking on the link at the bottom of the left hand page of each spread. Direct links to the websites you want All the websites mentioned in the magazine are linked. Roll over and click any website address and it will take you directly to the gallery’s website. Keep and fi le the issues on your desktop All the issue downloads are labeled with the issue number and current date. Once you have downloaded the issue you’ll be able to keep it and refer back to all the articles. Print out any article or Advertisement Print out any part of the magazine but only in low resolution. Subscriber Security We value your business and understand you have paid money to receive the virtual magazine as part of your subscription. Consequently only you can access the content of any issue. -

A Finding Aid to the Dixie Selden Papers, 1837-1936, 1993-2001, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Dixie Selden papers, 1837-1936, 1993-2001, in the Archives of American Art Hilary Price 2015 November 4 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1890s-1930s................................................. 4 Series 2: Correspondence, circa 1998, 1837-1935.................................................. 5 Series 3: Writings, circa 1890s-1930s..................................................................... 6 Series 4: Diaries, 1878-circa 1934.......................................................................... -

San Diego History Center Is a Museum, Education Center, and Research Library Founded As the San Diego Historical Society in 1928

The Journal of San Diego Volume 61 Winter 2015 Numbers 1 • The Journal of San Diego History Diego San of Journal 1 • The Numbers 2015 Winter 61 Volume History Publication of The Journal of San Diego History is underwritten by a major grant from the Quest for Truth Foundation, established by the late James G. Scripps. Additional support is provided by “The Journal of San Diego History Fund” of the San Diego Foundation and private donors. The San Diego History Center is a museum, education center, and research library founded as the San Diego Historical Society in 1928. Its activities are supported by: the City of San Diego’s Commission for Arts and Culture; the County of San Diego; individuals; foundations; corporations; fund raising events; membership dues; admissions; shop sales; and rights and reproduction fees. Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. The paper in the publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Science-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Front Cover: Clockwise: Casa de Balboa—headquarters of the San Diego History Center in Balboa Park. Photo by Richard Benton. Back Cover: San Diego & Its Vicinity, 1915 inside advertisement. Courtesy of SDHC Research Archives. Design and Layout: Allen Wynar Printing: Crest Offset Printing Editorial Assistants: Travis Degheri Cynthia van Stralen Joey Seymour The Journal of San Diego History IRIS H. W. ENGSTRAND MOLLY McCLAIN Editors THEODORE STRATHMAN DAVID MILLER Review Editors Published since 1955 by the SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY 1649 El Prado, Balboa Park, San Diego, California 92101 ISSN 0022-4383 The Journal of San Diego History VOLUME 61 WINTER 2015 NUMBER 1 Editorial Consultants Published quarterly by the San Diego History Center at 1649 El Prado, Balboa MATTHEW BOKOVOY Park, San Diego, California 92101. -

Harvest Dance, 1893–94 Art Museum Purchase, 1894.10 Family Events Such As Holidays, Weddings, Birthdays, Religious Events, and Friendly Gatherings

Why Do We Dance? teacher information unit overview focus art work Dance and movement are a part of every community. It can be an Joseph Henry Sharp (1859–1953) impromptu expression of feelings or part of a more formal celebration. United States (Cincinnati) Dancing occurs in all communities, often prompted by cultural or Harvest Dance, 1893–94 Art Museum Purchase, 1894.10 family events such as holidays, weddings, birthdays, religious events, and friendly gatherings. focus book Students are naturally interested in dance and movement. It can M.C. Helldorfer either be an impromptu expression of emotions or part of a planned Got to Dance. event or celebration. This lesson will facilitate connecting this interest New York: Doubleday Books for to students’ personal experiences. You will provide opportunities Young Readers, 2004 to view and discuss examples of dance events and will provide an opportunity in the classroom for students to interpret what they have experienced in a classroom dance area. grade level: pre-K (ages 3–5) 37 unit objectives about the artist • Students closely examine several works of art from the A traveler at heart, Joseph Henry Sharp’s art and Cincinnati Art Museum’s permanent collection, including teaching have made significant contributions to the Focus Artwork Harvest Dance, by Joseph Henry Sharp. city of Cincinnati. Sharp was born on September 27, • Students experience dance and movement 1859, in Bridgeport, Ohio, and was raised by his father in the classroom and connect it to their own William Henry Sharp, a merchant. Although Sharp and personal and cultural experiences. his brother, Avery, were brought up in Ironton, Ohio, by 1873, Joseph sought art instruction in Cincinnati. -

Piper – Exanimate Subjects

ISSN: 2471-6839 Exanimate Subjects: Taxidermy in the Artist’s Studio Corey Piper University of Virginia Fig. 1. William Merritt Chase, The Turkish Page (The Unexpected Intrusion), 1876. Oil on canvas, 48 ½ x 37 1/8 in. Cincinnati Art Museum. Gift of the John Levy Galleries / Bridgeman Images. In the course of researching my dissertation “Animal Pursuits: Hunting and the Visual Arts in Nineteenth-Century America,” I have often had occasion to consider (and sometimes lament) the unequal relationships between humans and animals that are frequently pictured in art. I have found taxidermy to be a potent material embodiment of this power dynamic that somewhat surprisingly connects a wide variety of nineteenth- century visual history, encompassing the work of Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), Victorian home furnishings, academic painting, and other visual realms. While the presence of taxidermy in nineteenth-century life is well documented, it has been more challenging to trace its intersection with the fine arts. References to artists such as Piper, Corey. “Exanimate Subjects: Taxidermy in the Artist’s Studio.” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 2 no. 1 (Summer, 2016). https:// doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1549. Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) who employed taxidermy in the studio are scattered throughout the literature on nineteenth-century art, but relatively little material or documentary record of the practice remains.1 I was thrilled, however, to find a piece of visual evidence hiding in plain sight within a photograph of the studio of William Merritt Chase (1849–1916) at the Archives of American Art that allowed for the concrete determination of an artist’s use of a taxidermy model in the construction of a painting. -

Research Resources at the Smithsonian American Art Museum Amelia A

From La Farge to Paik Research Resources at the Smithsonian American Art Museum Amelia A. Goerlitz A wealth of materials related to artistic interchange between the United States and Asia await scholarly attention at the Smithsonian Institution.1 The Smithsonian American Art Museum in particular owns a remarkable number of artworks that speak to the continuous exchange between East and West. Many of these demonstrate U.S. fascination with Asia and its cultures: prints and paintings of America’s Chinatowns; late-nineteenth- century examples of Orientalism and Japonisme; Asian decorative arts and artifacts donated by an American collector; works by Anglo artists who trav- eled to Asia and India to depict their landscapes and peoples or to study traditional printmaking techniques; and post-war paintings that engage with Asian spirituality and calligraphic traditions. The museum also owns hundreds of works by artists of Asian descent, some well known, but many whose careers are just now being rediscovered. This essay offers a selected overview of related objects in the collection. West Looks East American artists have long looked eastward—not only to Europe but also to Asia and India—for subject matter and aesthetic inspiration. They did not al- ways have to look far. In fact, the earliest of such works in the American Art Mu- seum’s collection consider with curiosity, and sometimes animosity, the presence of Asians in the United States. An example is Winslow Homer’s engraving enti- tled The Chinese in New York—Scene in a Baxter Street Club-House, which was produced for Harper’s Weekly in 1874. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia americká architektúra - pozri chicagská škola, prériová škola, organická architektúra, Queen Anne style v Spojených štátoch, Usonia americká ilustrácia - pozri zlatý vek americkej ilustrácie americká retuš - retuš americká americká ruleta/americké zrnidlo - oceľové ozubené koliesko na zahnutej ose, užívané na zazrnenie plochy kovového štočku; plocha spracovaná do čiarok, pravidelných aj nepravidelných zŕn nedosahuje kvality plochy spracovanej kolískou americká scéna - american scene americké architektky - pozri americkí architekti http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_architects americké sklo - secesné výrobky z krištáľového skla od Luisa Comforta Tiffaniho, ktoré silno ovplyvnili európsku sklársku produkciu; vyznačujú sa jemnou farebnou škálou a novými tvarmi americké litografky - pozri americkí litografi http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_printmakers A Anne Appleby Dotty Atti Alicia Austin B Peggy Bacon Belle Baranceanu Santa Barraza Jennifer Bartlett Virginia Berresford Camille Billops Isabel Bishop Lee Bontec Kate Borcherding Hilary Brace C Allie máj "AM" Carpenter Mary Cassatt Vija Celminš Irene Chan Amelia R. Coats Susan Crile D Janet Doubí Erickson Dale DeArmond Margaret Dobson E Ronnie Elliott Maria Epes F Frances Foy Juliette mája Fraser Edith Frohock G Wanda Gag Esther Gentle Heslo AMERICKÁ - AMES Strana 1 z 152 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Charlotte Gilbertson Anne Goldthwaite Blanche Grambs H Ellen Day -

Real and Ideal Women of the Gilded Age

SCHEHERAZADE AND HER SISTERS: REAL AND IDEAL WOMEN OF THE GILDED AGE (or: GILDED AGE ART AND THE POLITICS OF GENDER) By Bram Dijkstra “The Earthly Woman (with a woman’s weakness, and a woman’s faults) seems less fair than her Ideal Image…the primal Eve of Paradise.” -- Owen Meredith (i.e. Edward R. Bulwer-Lytton, 1831-1891), After Paradise. “A society sprawling on materialism and wallowing in ostentatious display—what should it care for, or even know of, choiceness of taste and reverence for what is true in art?” -- Charles H. Caffin, The Story of American Painting (1907), 360. For most of Western history, men undoubtedly fantasized about “ideal images” of women far more than women bothered to idealize men. However, throughout the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth, men came to consider what they habitually identified as “the battle of the sexes,” one of the basic laws of nature. In particular, when, in the second half of the nineteenth century the theory of evolution began to take center stage in the imagination of most progressive intellectuals, this phrase came to be seen as justifying “man’s” struggle against the forces of “degeneration” (a counterforce to evolution widely thought to be generated by those women who proved unwilling to be shaped by men’s fantasies about them). During this period of rapid economic expansion driven by what came to be seen as “the struggle for existence,” the put-upon white—and preferably Aryan—male’s striving for a qualitative racial transcendence that would match their expanding material wealth, often seemed undercut by what was seen as women’s inability to abandon a static focus on issues of practical immediacy, such as their relentless pursuit of what was delicately identified as the male’s “vital essence.” In the face of women’s inability to evolve, the production of men’s “ideal images of women” came to be seen as a necessary form of encouragement to the less “fair,” the less tractable, “earthly women,” to give up their obstructive ways and instead become “angels” of passivity and submission.