Kathu Pan: Location and Significance a Report Requested by SAHRA for the Purpose of Nomination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fourth Review Idp 2016-2017

; FINAL APPROVED FOURTHFF REVIEWED IDP IDP DOCUMENT 2016-2017 i | Page: Final Approved Fourth Reviewed IDP 2016 - 2017 Table of Contents Foreword by the Mayor .......................................................................................................... v Foreword by the Municipal Manager ................................................................................ vii Executive summary ................................................................................................................ ix Acronyms ................................................................................................................................. xii Chapter 1.................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction ...…………………………………………………………………………………….1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2. Guiding Principles……………………………………………………………………………...1 1.2.1 National Government’s outcomes based on delivery .................................... 2 1.2.2 National Development Plan ................................................................................ 2 1.2.3 CoGTA- National KPA's for municipalities .......................................................... 2 1.2.4. New Growth Path………………………………………………………………………..2 1.2.5 Northern Cape Provincial Spatial Development framework(2012)…………….3 1.2.6 Northern Cape Growth and Development Strategy……………………………...3 -

14 Northern Cape Province

Section B:Section Profile B:Northern District HealthCape Province Profiles 14 Northern Cape Province John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipality (DC45) Overview of the district The John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipalitya (previously Kgalagadi) is a Category C municipality located in the north of the Northern Cape Province, bordering Botswana in the west. It comprises the three local municipalities of Gamagara, Ga- Segonyana and Joe Morolong, and 186 towns and settlements, of which the majority (80%) are villages. The boundaries of this district were demarcated in 2006 to include the once north-western part of Joe Morolong and Olifantshoek, along with its surrounds, into the Gamagara Local Municipality. It has an established rail network from Sishen South and between Black Rock and Dibeng. It is characterised by a mixture of land uses, of which agriculture and mining are dominant. The district holds potential as a viable tourist destination and has numerous growth opportunities in the industrial sector. Area: 27 322km² Population (2016)b: 238 306 Population density (2016): 8.7 persons per km2 Estimated medical scheme coverage: 14.5% Cities/Towns: Bankhara-Bodulong, Deben, Hotazel, Kathu, Kuruman, Mothibistad, Olifantshoek, Santoy, Van Zylsrus. Main Economic Sectors: Agriculture, mining, retail. Population distribution, local municipality boundaries and health facility locations Source: Mid-Year Population Estimates 2016, Stats SA. a The Local Government Handbook South Africa 2017. A complete guide to municipalities in South Africa. Seventh -

2019/2020 Draft Idp Gasegonyana Local

2019/2020 DRAFT IDP GASEGONYANA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY Ga-Segonyana Local Municipality 2019/2020 Draft IDP Page 1 Table of Contents Section A .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Vision of Ga-Segonyana Local Municipality................................................................................... 8 1.1.1 Vision.................................................................................................................................8 1.1.2 Mission ..............................................................................................................................9 1.1.3 Values .............................................................................................................................. 10 1.1.4 Strategy Map ................................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Who Are We? ........................................................................................................................ 14 1.2.1 The Strategic Perspective.................................................................................................. 15 1.3 Demographic Profile of the Municipality ................................................................................ 17 1.4 Powers and Functions of the Municipality .............................................................................. 27 1.5 Process followed to develop the IDP ..................................................................................... -

New Radiometric Ages for the Fauresmith Industry from Kathu Pan, Southern Africa: Implications for the Earlier to Middle Stone Age Transition

Journal of Archaeological Science 37 (2010) 269–283 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jas New radiometric ages for the Fauresmith industry from Kathu Pan, southern Africa: Implications for the Earlier to Middle Stone Age transition Naomi Porat a,*, Michael Chazan b, Rainer Gru¨ n c, Maxime Aubert c, Vera Eisenmann d, Liora Kolska Horwitz e a Geological Survey of Israel, 30 Malkhe Israel Street, Jerusalem 95501, Israel b Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto, 19 Russell Street, Toronto, Ontario M5S 2S2, Canada c Research School of Earth Sciences, Building 61 (HB-B), Mills Rd., The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia d MNHN, De´partement Histoire de la Terre, CP38, UMR 5143 du CNRS, Pale´obiodiversite´ et Pale´oenvironnements, 8 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France e National Natural History Collections, Faculty of Life Sciences, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem 91904, Israel article info abstract Article history: The Fauresmith lithic industry of South Africa has been described as transitional between the Earlier and Received 8 April 2009 Middle Stone Age. However, radiometric ages for this industry are inadequate. Here we present Received in revised form þ140 a minimum OSL age of 464 Æ 47 kyr and a combined U-series–ESR age of 542 107 kyr for an in situ 17 September 2009 À Fauresmith assemblage, and three OSL ages for overlying Middle and Later Stone Age strata, from the site Accepted 21 September 2009 of Kathu Pan 1 (Northern Cape Province, South Africa). These ages are discussed in relation to the available lithostratigraphy, faunal and lithic assemblages from this site. -

Senior Electricians

GAMAGARA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY EXTERNAL ADVERTISEMENT Gamagara Local Municipality with its head office in Kathu and located in the John Taolo Gaetsewe Region, Northern Cape province, is an equal opportunity employer and invites applications from suitably qualified persons for the following permanent positions: POSITION : SENIOR ELECTRICIAN DEPARTMENT : TECHNICAL SERVICES SECTION : ELECTRICAL SERVICES WORKSTATION : OLIFANTSHOEK SALARY : TASK GRADE 12: R380 436.00 – R428 328.00 (Plus benefits: Pension, Medical aid scheme, Group life insurance, Housing subsidy, 13th cheque) REFERENCE NO : NOTICE: 2020/38 Qualifications and Experience: Relevant electrical experience (3–5 years) as a qualified electrician. N3 plus Electrical Trade Tested Artisan. Code 10 Driver’s (C1) license with PrDP. Requirements and Skills: Operating Regulations for High Voltage Systems (ORHVS) and be authorised to switch up to 11 000 Volts. Computer literate. Electrical maintenance experience on infrastructure networks. Installs, tests, connects, commissions, maintains and modifies electrical equipment, wiring and control systems. Key Performance Areas: Co-ordinates and controls the set-up, work in progress and completion of specialized tasks activities associated with high/medium/low voltage electrical installation, maintenance and repair including, monitoring and correcting support personnel productivity and performance and, attending to routine/ general administrative recording requirements contributing to the accomplishment of departmental objectives. Maintenance of electrical machinery and installations. Fault identification and repairs to medium and low voltage reticulation systems. Switching on LV and MV networks. Streetlight maintenance. The reading and interpretation of drawings, work order, detailing layout of specifications. The appointee must be willing to work overtime if and when needed. The implementation and maintenance of safety and personal protective measures. -

NC Sub Oct2016 ZFM-Postmasburg.Pdf

# # !C # ### # ^ #!.C# # !C # # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # ## # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C # # # # # ## # #!C# # # # # # #!C # # ^ ## # !C# # # # # # ## # # # # #!C # # ^ !C # # # ^# # # # # # # ## ## # ## # # !C # # # !C# ## # !C# # ## # # # # #!C # # # #!C##^ # # # # # # # # # # # #!C# ## ## # ## # # # # # # ## # ## # # # ## #!C ## # ## # # !C### # # # # # # # # # # # # !C## # # ## #!C # # # ##!C# # # # ##^# # # # # ## ###!C# # ## # # # ## # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # ## # # ## !C# #^ # #!C # # !C# # # # # # # ## # # # # # ## ## # # # # # !C # # ^ # # # ### # # ## ## # # # # ### ## ## # # # # !C# # !C # # # #!C # # # #!C# ### # #!C## # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## # ## ## # # ## # # ## # # # # # # ## ### ## # ##!C # ## # # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ ## # #### ## # # # # # # #!C# # ## # ## #!C## # #!C# ## # # !C# # # ##!C#### # # ## # # # # # !C# # # # ## ## # # # # # ## # ## # # # ## ## ##!C### # # # # # !C # !C## #!C # !C # #!.##!C# # # # ## # ## ## # # ### #!C# # # # # # # ## ###### # # ## # # # # # # ## ## #^# ## # # # ^ !C## # # !C# ## # # ### # # ## # ## # # ##!C### ##!C# # !C# ## # ^ # # # !C #### # # !C## ^!C#!C## # # # !C # #!C## #### ## ## #!C # ## # # ## # # # ## ## ## !C# # # # ## ## #!C # # # # !C # #!C^# ### ## ### ## # # # # # !C# !.### # #!C# #### ## # # # # ## # ## #!C# # # #### # #!C### # # # # ## # # ### # # # # # ## # # ^ # # !C ## # # # # !C# # # ## #^ # # ^ # ## #!C# # # ^ # !C# # #!C ## # ## # # # # # # # ### #!C# # #!C # # # #!C # # # # #!C #!C### # # # # !C# # # # ## # # # # # # # # -

GG 42343, Gon

4 No. 42343 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 28 MARCH 2019 GOVERNMENT NOTICES • GOEWERMENTSKENNISGEWINGS Justice and Constitutional Development, Department of/ Justisie en Staatkundige Ontwikkeling, Departement van No. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT 2019 NO. 507 28 MARCH 2019 507 Magistrates’ Courts Act (32/1944): Variation of a notice in respect of the Northern Cape Regional Division 42343 MAGISTRATES' COURTS ACT, 1944 (ACT NO. 32 OF 1944): VARIATION OF A NOTICE IN RESPECT OF THE NORTHERN CAPE REGIONAL DIVISION I,Tshililo Michael Masutha, Minister of Justice and Correctional Services, acting under section 2(1)(I) of the Magistrates' Courts Act, 1944 (Act No. 32 of 1944), hereby vary GovernmentNotice No. 219published in GovernmentGazette No. 26091 of 27 February 2004, by the substitution of item 7 (Northern Cape) of the Schedule to the said Notice for item 7 in the accompanying Schedule. This Notice shall be deemed to have come into effect on 1 May 2018. Givenundermy. handat .............. onthisthe dayof This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za STAATSKOERANT, 28 MAART 2019 No. 42343 5 SCHEDULE Item Regional Division Consisting of the following districts 7 Northern Cape Frances Baard (1) John Taolo Gaetsewe (2) Namaqualana (3) Pixley Ka Seme (4) ZF Mgcawu (5) (1) Consisting of Kimberley main seat with Modderrivier as a place for the holding of court. Barkly West, Galeshewe, Hartswater, Jan Kempdorp and Warrenton as sub - districts. Delportshoop and Windsorton as places for the holding of courts under Barkley West. Pampierstad as a place for the holding of court under Hartswater (2). Consisting of Kuruman main seat with Tsineng as a place for the holding of court. -

The Socio-Economic Wellbeing of Small Mining Towns in the Northern Cape

THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC WELLBEING OF SMALL MINING TOWNS IN THE NORTHERN CAPE by Avril Edward Mathew Gardiner Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Professor SE Donaldson Department of Geography and Environmental Studies March 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ii DECLARATION By submitting this report electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained herein is my own original work, that I am the sole author (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication hereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights, and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za iii ABSTRACT With South Africa being a developing country in many respects, the management of natural resources is of high importance. It should therefore be determined how these resources are managed and what happens to the capital generated by the extraction of these resources. The resource curse hypothesis will be used as a base to understand why there are so many underdeveloped communities in places where these resources are extracted. The aim of this study was to investigate the nature and extent of the economic and social conditions of the communities of small mining towns in the Northern -

Integrated Development Plan Gamagara Local Municipality

Year: 2017-2022 Integrated Development Plan Gamagara Local Municipality i | Page: DRAFT IDP 2017 - 2022 Table of Contents Foreword by the Mayor ......................................................................................................... v Foreword by the Municipal Manager ................................................................................ vii Executive summary ................................................................................................................ ix Acronyms .................................................................................................................................xii Chapter 1.................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Legislative Framework…….…………………………………………………………………….1 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2. Legislative Frameworks..……………………………………………………………………...1 1.2.1 Constitution of Republic Of South Africa (1996) ........................................................ 1 1.2.2 White Paper on Local Government (1998) ................................................................. 2 1.2.3 Municipal Systems Act ................................................................................................... 2 1.2.4. National Development Plan..……………………………………………………………..2 1.2.5 National Outcomes…………………………………………………………...…………….3 1.2.6 Provincial Spatial Development plan…………………………………………………...3 -

Proposed Development of the Kuruman Phase 1 and 2 Wind Energy Facilities and Supporting Electrical Infrastructure to the Propose

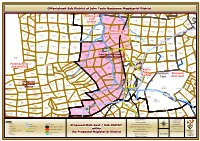

PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT OF THE KURUMAN PHASE 1 AND 2 WIND ENERGY FACILITIES AND SUPPORTING ELECTRICAL INFRASTRUCTURE TO THE PROPOSED WIND ENERGY FACILITIES, KURUMAN, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE February 2018 BACKGROUND INFORMATION DOCUMENT INTEGRATED PUBLIC PARTICIPATION PROCESS FOR THE PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT OF THE KURUMAN PHASE 1 AND 2 WIND ENERGY FACILITIES AND SUPPORTING ELECTRICAL INFRASTRUCTURE TO THE PROPOSED WIND ENERGY FACILITIES, KURUMAN, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE BACKGROUND Mulilo Renewable Project Developments (Pty) Ltd (hereafter, “Mulilo”) is proposing to construct two Wind Energy Facilities (WEFs), namely Kuruman Phase 1 WEF and Kuruman Phase 2 WEF and supporting electrical infrastructure, in the Ga-Segonyana Local Municipality and the John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipality, 8 km and 37 km south west from Kuruman and from Kathu, respectively, in the Northern Cape Province. The proposed projects are being developed to generate electricity via wind energy which will feed into a nd supplement the national electricity grid. The respective farms portions affected by the two WEFs and the supporting electrical infrastructure and the relative location of the proposed projects are shown on the opposite page. Since the WEFs and supporting electrical infrastructure are proposed within the same geographical area, an integrated Public Participation Process (PPP) will be undertaken for the proposed projects. However, separate applications for Environmental Authorisation (EA) will be lodged with the National Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA). The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) as been appointed as the independent Environmental Assessment Practitioner (EAP) to manage the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for the proposed wind farms and the Basic Assessment (BA) process for the proposed supporting electrical infrastructure. -

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Northern Cape

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Northern Cape Permit Number Primary Name Address 202103969 Coleberg Correctional Petrusville road, services Colesberg Centre, Colesberg Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103950 Upington Clinic Schroder Street 52 Upington ZF Mgcawu DM Northern Cape 202103841 Assmang Blackrock Sering Avenue Mine OHC J T Gaetsewe DM Northern Cape 202103831 Schmidtsdrift Satellite Sector 4 Clinic Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103744 Assmang Khumani Mine 1 Dingleton Road, Wellness Centre Dingleton J T Gaetsewe DM Northern Cape 202103270 Prieska Clinic Bloekom Street, Prieska, 8940 Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103040 Kuyasa Clinic Tutuse Street Kuyasa Colesberg Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103587 Petrusville Clinic Thembinkosi street, 1928 New Extention Petrusville Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103541 Keimoes CHC Hoofstraat 459 ZF Mgcawu DM Northern Cape 202103525 Griekwastad 1 Moffat Street (Helpmekaar) CHC Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape Updated: 30/06/2021 202103457 Medirite Pharmacy - Erf 346 Cnr Livingstone Kuruman Road & Seadin Way J T Gaetsewe DM Northern Cape 202103444 Progress Clinic Bosliefie Street,Progress Progress,Upington ZF Mgcawu DM Northern Cape 202103443 Sarah Strauss Clinic Leeukop Str. Rosedale,Upington ZF Mgcawu DM Northern Cape 202103442 Louisvaleweg Clinic Louisvale Weg Upington ZF Mgcawu DM Northern Cape 202103441 Lehlohonolo Adams Monyatistr 779 Bongani Clinic Douglas Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103430 Florianville (Floors) Stokroos Street, Clinic Squarehill Park, Kimberley -

NC Sub Oct2016 JTG-Olifantshoek

# # !C # # ### !C^# !.!C# # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # #!C# # # # # ^ # !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # #!C # # # # # # !C # #^ # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # ## !C # # # # # # # !C# ## # # #!C # !C # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # # ## # # # # # # # # !C# # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # !C# !C # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # #!C ## # ##^ # !C #!C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # !C ## # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # ## # # !C # !C # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C # # # # !C## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # !C #!C # # # # # #!C # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # ### !C # # # # !C !C# # ## # # # ## !C !C #!. # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C# # # # ## # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## ### #^ # # # # # # # # ^ # !C ## # # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # ## # ## # !C ## !C## # # # # ## # !C # ## !C# ## # # ## # !C # # ^ # !C ## # # # !C# ^# # # !C # # # !C ## # # #!C ## # # # # # # # # # ## # !C## ## # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # !C # # ^ # ## # # # # !C # # # # # # # !. # # #!C # # # # # !C # # ##