Liberation Through Sexualization: the Dichotomous Nature of Burlesque Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Las Vegas Data Book

082011B City of Las Vegas Economic and Urban Development Department & Redevelopment Agency Economic and Urban Development Introduction Economic and Urban Develpment Department The Economic and Urban Development Department (EUD) creates, coordinates and encourages new development and redevelopment throughout the city of Las Vegas. It increases and diversifies the city’s economic base, and creates jobs, through business attraction, retention and expansion programs. In addition, this newly expanded department now includes employees who oversee and manage local, state and federal grants used to provide public services, develop public facilities and support affordable housing for low income Las Vegas families. The majority of grants are received from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development as part of entitlement funding. These grants are used for homeless services and shelter, senior nutrition, rent assistance and new construction of affordable housing and community centers, to name a few. The EUD coordinates with the city of Las Vegas Redevelopment Agency on day-to-day operations, economic development, job creation and long-term strategic goals. Las Vegas Redevelopment Agency The Las Vegas Redevelopment Agency (RDA) promotes the redevelopment of downtown Las Vegas and surrounding older commercial districts by working with developers, property owners and the community to accomplish beneficial revitalization efforts, create jobs and eliminate urban decay. The Las Vegas Redevelopment Area encompasses 3,948 acres. The area roughly includes the greater downtown Las Vegas area east of I-15, south of Washington Avenue, north of Sahara Avenue and west of Maryland Parkway. It also includes the Charleston Boulevard, Martin L. King Boulevard and Eastern Avenue corridors. -

Communityw O 7 S 0 B &

INC PULATION REA PO DU SE RING U 20 NL % 13 2 V EN 7, 5 RO 8 . L 2 C LM 4 S 7 N EN 8 Y 062,2 3 T , 5 E 6 T E 3 NR , G 2 N O 6 A % EW N L I R COM S LM 2 G VE E C E 9 N A A RS N N I L RE T A .6 FR 3 V 3 I N 3 O , M E 3 L IO NR 9 U T OL F A LM 5 N E O S E ALIFO N L C R T R N M T A I U 4 U A S Q . 7 T E A O . o C 0 R C 0 0 9 E M 1 A P 9 FO 0 F G M IN R N O E T O T IN H 1 S S T E N O U E F C O 8 1 I C H G . R O S A 9 T R T N 7 I E 9 M V 0 E A 6 Y S R $ T S 3,086,745,000(ASSISTED BY LVGEA) S E NEW COMPANIES U N I D 26 S N I ANNUAL HOME SALES N 7 U 4 R EMPLOYMENT 5 T E E , COMMUNITYW O 7 S 0 B & 4 A T , 5 L 7 las vegasA perspective E 895,700 , 9.5% 6 L 7 6 UNEMPLOYMENT 4 0 RATE 6 E M M IS E LU A R LUM VO P TOU VO R M A CO ITOR E L R M VIS G TE S A T M N O M V E 6 H O G M ER M SS O $ . -

Blue Star Museums Press Release

[email protected] (888) 661-6465 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BURLESQUE HALL OF FAME TO PARTICIPATE IN BLUE STAR MUSEUMS Museum offering free admission to active military and their family members this summer [Las Vegas, NV – May 9, 2019] The Burlesque Hall of Fame will join museums nationwide in participating in the tenth summer of Blue Star Museums, a program which provides free admission to our nation’s active-duty military personnel and their families this summer. The 2019 program will begin Saturday, May 18, 2019, Armed Forces Day, and end on Monday, September 2, 2019, Labor Day. More information about Blue Star Museums and a list of participating museums can be found at arts.gov/bluestarmuseums. Blue Star Museums is an initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts in collaboration with Blue Star Families, the Department of Defense, and more than 2,000 museums nationwide. First Lady of the United States Melania Trump and Second Lady of the United States Karen Pence are honorary co-chairs of Blue Star Museums 2019. “The burlesque world has always had a special relationship with the US military,” says Executive Director Dustin M. Wax. “Burlesque performers like Gypsy Rose Lee, Ann Corio, Mae West, and Sherry Britton travelled the world with the USO, posed for pinups, led book drives for overseas service members, and of course entertained troops in theaters and clubs around the country. We are proud to continue that special relationship and to share that history with today’s generation of men and women serving in the armed forces.” “The Defense Department congratulates Blue Star Families and the National Endowment for the Arts on reaching an incredible milestone: ten years of service to the military community though Blue Star Museums,” said A.T. -

Rose La Rose and the Re-Ownership of American Burlesque, 1935-1972

TAUGHT IT TO THE TRADE: ROSE LA ROSE AND THE RE-OWNERSHIP OF AMERICAN BURLESQUE, 1935-1972 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Elizabeth Wellman Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Jennifer Schlueter, Advisor Beth Kattelman Joy Reilly Copyright by Elizabeth Wellman 2015 ABSTRACT Declaring burlesque dead has been a habit of the twentieth century. Robert C. Allen quoted an 1890s letter from the first burlesque star of the American stage, Lydia Thompson in Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture (1991): “[B]urlesque as she knew it ‘has been retired for a time,’ its glories now ‘merely memories of the stage.’”1 In 1931, Bernard Sobel opined in Burleycue: An Underground History of Burlesque Days, “Alas! You will never get a chance to see one of the real burlesque shows again. They are gone forever…”2 In 1938, The Billboard published an editorial that began, “On every hand the cry is ‘Burlesque is dead.’”3 In fact, burlesque had been declared dead so often that editorials began popping up insisting it could be revived, as Joe Schoenfeld’s 1943 op-ed in Variety did: “[It] may be in a state of putrefaction, but it is a lusty and kicking decomposition.”4 It is this “lusty and kicking decomposition” which characterizes the published history of burlesque. Since its modern inception in the late nineteenth century, American burlesque has both been framed and framed itself within this narrative of degeneration. -

Fiscal Year 2011 in Review

CITY OF LAS VEGAS ECONOMIC AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS FISCAL YEAR 2011 IN REVIEW The front cover of this publication features a rendering of The Smith Center for the Performing Arts, which is currently under construction in Symphony Park™ in downtown Las Vegas. Named in honor of Fred W. and Mary B. Smith, this performing arts center will be home to Nevada Ballet Theatre, Las Vegas Philharmonic and first-run touring attractions. It was designed by David M. Schwartz. The opening is planned for spring 2012. LAS VEGAS ECONOMIC AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT Now more than ever, the city of Las Vegas is focused on new businesses, job creation and building on the success that has come to fruition in the downtown area. The city’s multi-faceted and multi-functional Economic and Urban Development Department (EUD) serves these purposes. Currently, the department’s responsibilities include the following: Negotiating new development contracts and redevelopment projects. Encouraging entrepreneurship and startups through an established business incubator, technology transfer and venture capital investment. Regional and international business and investor attraction efforts. Symphony Park urban community development. Mart attraction (e.g., the 5-million-square-foot World Market Center Las Vegas). Fast track assistance with expediting business-related permits, licenses and entitlements. Managing a real estate portfolio, including land acquisitions, leasing and sales. Connecting retail developers, commercial brokers and property owners with appropriate high-quality tenants. Visual Improvement Program assistance, which aids businesses with upgrading their exteriors and reducing urban decay. Tax Increment Financing assistance. Researching and compiling data sought by businesses, concentrating on information specific to the city of Las Vegas and Redevelopment Area. -

The Untitled Black Burlesque History Project

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Winter 1-5-2017 The Untitled Black Burlesque History Project Sekiya Dorsett How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/243 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Fall 12-20-2017 The Untitled Black Burlesque History Project Sekiya Dorsett CUNY Hunter College The Untitled Black Burlesque History Project by Sekiya Dorsett Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Integrated Media Arts, Hunter College The City University of New York Fall 2017 Thesis Sponsor: Dec 20, 2017 Date Signature Tami Gold Dec 20, 2017 Date Signature of Second Reader Rachel Stevens Dec 20, 2017 Date Signature of Third Reader Ricardo Miranda 2 Abstract The Untitled Black Burlesque History Project is a character driven short documentary featuring Chicava Honeychild, a neo-burlesque1 dancer who is unearthing a hidden Black burlesque history. As Chicava searches for her “stripper grandmas,” she mentors a new generation of burlesque performers who are of women of color. Chicava Honeychild first meeting with Black burlesque Jean Idelle is interwoven with the burlesque journey of Henrietta, Chicava Honeychild’s burlesque student. As Henrietta is honing her burlesque craft in preparation for her first performance, we learn about Jean’s dynamic life as a burlesque dancer in the 1940s and 1950s. -

Things to Do in and Around Las Vegas

SOHA 2020: A Las Vegas Guide 30 min. Red Rock Canyon National prehistory and history of the park and nearby Things to Do in and Conservation Area presents awe-inspiring views region. The park features many short and easy most wouldn't expect to see near a major hikes for a variety of skill levels featuring Around Las Vegas metropolitan city. In contrast to the bright lights petroglyphs, slot canyons, movie sets, domes, and hype of the Strip, Red Rock offers desert and many other unique rock formations. Make beauty, towering red cliffs and abundant sure to bring water. $10 per vehicle. Public Lands wildlife. $15 per vehicle Las Vegas is surrounded by a sea of federal land Sloan Canyon National Recreation Area and public spaces. Beyond the lights and buzz of the Las Vegas strip, Southern Nevada has a 40 min. Sloan Canyon National Conservation Museums diverse array of public lands from rain islands to Area’s 48,438 acres provide peace and solitude endangered habitats, from the oldest trees on for those who visit the unique scenic and Although opulent casinos and overblown pools earth, to cartoonish red slot canyons and rock geologic features and extraordinary cultural have helped put Las Vegas on the map, there is formations. These protected locations display resources. The centerpiece of the area is the much more to the city, including its collection both the natural and human history of an often Sloan Canyon Petroglyph Site, one of the most of Museums. From the Neon Museum to the misunderstood space. significant cultural resources in Southern National Atomic Testing Museum, these venues Nevada. -

Political Challenges in the Neo-Burlesque Spectacle

WiN: The EAAS Women’s Network Journal Issue 2 (2020) Cyberlesqued Re/Viewings: Political Challenges in the Neo-burlesque Spectacle Mariza Tzouni ABSTRACT: Provided that the 1990s was characterized as an era of newness with the insertion of extreme technological advances, the rise of multiculturalism, new media expansion and the appearance of the World Wide Web, neo-burlesque appeared as an all-new form of entertainment which de/re/contextualized the act of viewing. Burlesque has been metamorphosed through the occurrence of neo-burlesque as an attempt to stress newness into the old; that is to re-generate a nationalized theatrical sub/genre to an inter/nationalized cyber/spectacle which re/acts against the sociopolitical distresses of the twenty-first century. Initiated with the Yahoo Group along with a plethora of online groups and blogs which have sprung till then, the Internet manages to weave a nexus among producers, performers and fans inter/nationally. It has also enabled neo-burlesque to cross over the national borders and break those barriers which were formerly narrowed to mainly the U.S theatrical reality. In this milieu, the rise of social media; namely, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, have facilitated both the performers’ and the spectators’ re/viewings since the former can re/present and promote their neo-burlesque pieces as well as advertise their campaigns and products increasing in this way their popularity while the latter, in their turn, can be informed about the performers’ recent activities, purchase goods or follow their accounts as evidence of support or even condemnation. Moreover, YouTube has revolutionized spectatorship since neo-burlesque performers of versatile performing styles, age, race and body sizes launch their work in order to gain popular appeal through the gathering of views claiming in this way an increase of paychecks and attendance to distinguished events and venues. -

Lvb-0618-Bhof

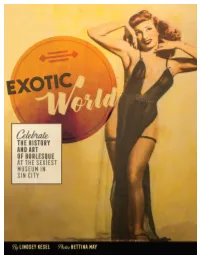

Pictured from left, t the spot “where the burlesque legend strip meets the tease,” the Dusty Summers; Miss Burlesque Hall of Fame is Exotic World 2011 boldly smashing stereotypes Indigo Blue; Miss Exotic World 2010 Roxi of museums everywhere. Sterile walls A D’lite; Tempest Storm, and stoic guides are replaced by campy the Queen of Exotic costumes and cotton candy-colored Dancers; BHoF staff backdrops. Instead of priceless paintings member Buttercup; Las or artifacts encased in glass, visitors Vegas Mayor Carolyn Goodman; Miss Exotic interact with the vintage hand-me- World 2005 Michelle downs of burlesque sex symbols—like L’amour; BHoF board Jayne Mansfield's heart-shaped love seat member Melody and the oversized martini glass Dita Von Sweets; Marinka, also Teese made famous as a stage prop. known as Queen of Unveiled this past April, BHoF’s the Amazons; Best Boylesque winner 2015 newest incarnation is 3,000 square feet Matt Finish; BHoF of flirtatious fun celebrating the art Executive Director of the tease just a stone’s throw from Dustin Wax. the Las Vegas Strip. A major upgrade from its former space of just 200 square feet, the museum gives guests the rare playful props stood guard around an inground pool, hinting that this was no opportunity to peek under the skirt place for the straight-laced. of the burlesque—with everything After Lee’s death in 1990, fellow entertainer Dixie Evans continued her from autographed photos and corset- friend’s legacy, greeting guests in glittery gowns and feather boas, eventually clad mannequins to theater marquees adding an attraction that put the museum on the map—the Miss Exotic World and giant mounted posters from hit Pageant, a striptease contest where spectators could indulge their skin-bearing productions. -

THE ROUTLEDGE COMPANION to GENDER, SEX and LATIN “A Sharp Observer and Scholarly Commentator, Aldama Gives Sex and Gender a New Twist

THE ROUTLEDGE COMPANION TO GENDER, SEX AND LATIN “A sharp observer and scholarly commentator, Aldama gives sex and gender a new twist. He gathers expert analysts who put sex and gender into contemporary but unfamiliar contexts of AMERICAN CI.JLT1:.J1~E popular culture. They take us into national (Chile, Mexico, Brazil, Japanese Peru, Puerto Rico, Argentina, Cuba), pre—national ~Amerindian), and hemispheric transnational spaces (the U.S.— Mexico border, Budapest—Brazil, Japan—Peru, Cuba—U.S.) of cultural production. An absolutely essential resource for all those interested in the dynamic and varied ways that of sex and gender inform the shaping of pop culture in the Americas” Marta E. Sdnchez, author of Shakin’ Up Race and Gende,; Professor ~f Chicano, US Latino, and L.atin American Literature, Arizona State Universitp USA “Aldama’s Companion brings together under-explored intersectional identities and cultural Edited by Frederick Luis Aldama riches that provide the keys to understand the intricacies of Latin American culture. The essays shed light on how gender, sexuality, race, and class traverse all facets of our lives.This is a must— have for all Latin American Studies programs” Consuelo Martinez Reyes, Lecturer in Spanish Studies, Australian National University, Australia “More than ever, pop culture permeates every nook and cranny of our increasingly globalized world. It is unavoidable.Through richly varied theoretical approaches and methodologies, cov ering a broad range of topics from comics to futebol,Aldama’s Companion reframes -

Downtown LV Guide

VISITORS GUIDE It’s not just Vegas. It’s original Vegas. Photo by Derek Sola Photo by Todd Korga n Photo by Ryan Reason Photo by Lizter Van Orman 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 A A DOWNTOWN LAS VEGAS MAP KEY B WASHINGTON AVE. B 18b Las Vegas Arts District Fremont East Entertainment District Fremont Street Experience C C Cultural Corridor BONANZA RD. Symphony Park D D Parking BONANZA RD. MESQUITE AVE. City of Las Vegas, Las Vegas Boulevard State Scenic STEWART AVE. Byway – part of America’s Byways® Cultural Corridor Trail – 12 blocks E E 9TH ST. PKWY. OGDEN AVE. 10TH ST. 11TH ST. FREMONT ST. F F CARSON AVE. Sights and Amenities LEWIS AVE. BRIDGER AVE. G MAIN ST. G GRAND CENTRAL CLARK AVE. 12TH ST. 1 Las Vegas City Hall CASINO CENTER BLVD.3RD ST. 4TH ST. 2 Greyhound Bus Depot BONNEVILLE AVE. GARCES AVE. 3 Marriage License Bureau (Regional Justice Center) H MARTIN LUTHER KING BLVD. H GASS AVE. 4 863RVW2IÀFH LAS VEGAS BLVD. 7TH ST. 6TH ST. 5 Bonneville Transit Center HOOVER AVE. CHARLESTON BLVD. I COOLIDGE AVE. 8TH ST. I 1ST ST. UNION PACIFIC RAILROAD COMMERCEMAIN ST. ST. J J COLORADO AVE. K Imperial Ave. K Note: Map not to scale. MAIN ST. MAIN MAIN ST. MAIN WYOMING AVE. L L M M 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 CONTENTS 2 Short History of Las Vegas 5 Bars, Lounges & Nightclubs 9 Casinos 11 Museums & Attractions 21 Restaurants 27 Wedding Chapels 31 Transportation Use map on left to find locations listed in this guide (ex. -

SJMA Members at the $75 Level and Above Can Enjoy Benefits at the Following Museums

Reciprocal Membership Privileges: Museum members at the Dual/Family ($75) level and above receive reciprocal privileges at museums affiliated with the Western Museum Group (WMG). Those at the Young Professional ($100) level and above also receive reciprocal privileges at museums in the Museum Alliance Reciprocal Program (MARP), Reciprocal Organization of Associated Museums (ROAM) and also the North American Reciprocal Membership (NARM) programs. Please check with institution for their reciprocity policy. SJMA Members at the $75 level and above can enjoy benefits at the following museums: Western Museum Group (WMG) California Museum of Craft and Folk Art, SF Pacific Asia Museum, Pasadena Other Western States Carnegie Art Museum, Oxnard Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego & La Jolla San Jose Museum of Quilts and Textiles Bellevue Art Museum, WA Fresno Art Museum Museum of Craft and Folk Art, San Francisco Santa Barbara Museum of Art Missoula Art Museum, Montana Fresno Metropolitan Museum Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego Seymour Marine Discovery Center, Santa Cruz Phoenix Art Museum, AZ Long Beach Museum of Art National Steinbeck Center, Salinas UCR California Museum of Photography, Riverside Tucson Museum of Art and Historic Block, AZ Monterey Museum of Art Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach University Art Museum, Santa Barbara The Contemporary Museum, Honolulu The Museum of Art & History, Santa Cruz SJMA Members at the $100 level and above can also enjoy benefits at the following museums: Museum Alliance Reciprocal Program (MARP) North American Reciprocal Membership (NARM) Reciprocal Organization of Associated Museums (ROAM) Alabama Museum of Ventura County, Ventura The Dalí Museum Minnetrista Abroms-Engel Institute for Visual Arts MUZEO Museum and Cultural Center, Anaheim Dunedin Fine Art Center Snite Museum of Art Jule Collins Smith (JCS) Museum, Auburn Univ.